The following essay, presented here in its English original, is one of several new and newly translated pieces by Stig Sæterbakken to appear in Music & Literature no. 5, which devotes nearly 100 pages to the late Norwegian author.

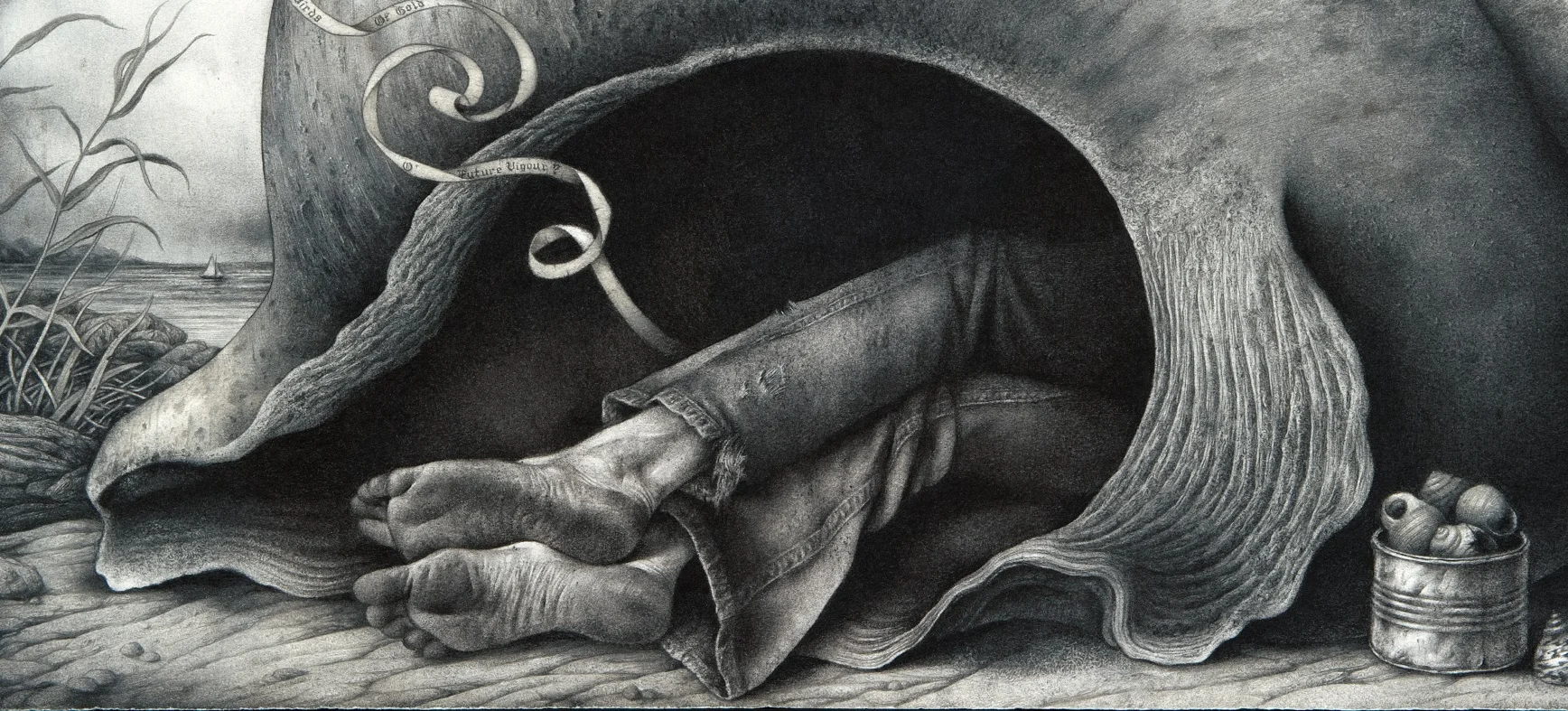

Sverre Malling, "Mask: Primates." 57 x 53 cm, 2013. Courtesy of the artist.

I

QUICQUID DEUS CREAVIT PURUM EST, it reads above the entrance to Tomba Emmanuelle, EVERYTHING CREATED BY GOD IS PURE, in what seems to be the perfect antithesis to the dark inferno of sex and death one enters seconds later. But only seems. For what, if not purity, is the very essence of Vita, with its never-ending cycle of birth, growth, and death, purity of vision, and purity of form, all of mankind’s vitality and anxieties and unspeakable fears frozen in almost ornamental patterns of naked figures? The scenes are those of both productive and counterproductive human activity, men and women engaged in Kama-Sutra-like lovemaking side by side with skulls and bones and decomposing corpses, with the ultimate synthesis of life and death conjured up in what is perhaps the most extreme image of them all, that of two skeletons copulating at the base of a monolith of levitating infants.

It wouldn’t be far-fetched to call it a marriage between Heaven and Hell, the heavy lumps of struggling bodies on each wall transforming into lighter elusive shapes as they hit the ceiling, evaporating into some unknown realm. Yes, Emanuel Vigeland’s Vita is Inferno and Paradiso combined, depicting raw nature with a sort of sublime dignity, the latter underlined by the fact that one has to lower one’s head when entering, bowing for what is slowly to become extinguishable in the semi-darkness of the crypt, placed in a small niche just above the entrance door, still, even after a while, only barely perceptible against the dark brown wall: a hollow stone—an urn—holding the artist’s ashes. It is as concrete—and as abstract—as it gets. And what a great metamorphosis as well: the artist’s studio turned into the artist’s tomb, the spirit of Vigeland forever contained within the walls of the magnificent brick building at Slemdal, with its legendary acoustics, creating droning dreamlike soundscapes out of the lightest footsteps, the slightest cough, a sigh, or even a single breath (the reverb lasting up to twenty seconds, I’ve been told). Why the hell isn’t every artist buried where he or she worked?

II

Inspired, possibly, by the shape of the room, I always think of Jonah and the whale whenever I visit Tomba Emmanuelle, the ceiling curving like gigantic ribs above me. And given the two representations of the artist himself, both in the right corner of the entrance wall, one—alive, brush and palette in hand, in the act of painting (Vita)—above the other—dead, with the palette and brushes scattered on the ground, as if the work itself has first exhausted him, then killed him—I can’t help thinking that there is a third representation as well, which is the crypt itself, and that while Dante and Virgil had to climb over Satan’s hairy body to get to Purgatorio, the dead Vigeland has left his mouth open, in rigor mortis, for us to climb in, down the throat and into the holy chambers of his chest and stomach, the naked bodies crawling all around us playing the role of the mental intestines, so to speak, of his—literally—inner world.

In that respect, Tomba Emmanuelle is as close a relative to Per Inge Bjørlo’s Inner Rooms (1984-1990) as it is to Michelangelo’s Last Judgment (1537-1541).

III

A wonderful sense of being consumed, this is what the Vigeland mausoleum offers its unprepared first-time visitor. But the feeling does not fade through repetition. On the contrary, I’d say. As if the knowledge of what awaits you heightens rather than diminishes this overwhelming sensation. And I guess that’s why so many visitors keep coming back: they want to be devoured again. And again. And again. And isn’t that what drives us, repeatedly, toward art in any form, the dream—however often it leads to disappointment—of being overpowered, shocked, overcome by horror and joy, the stubborn dream of becoming one with the object in question, melting into it, rather than standing at a distance watching it, analyzing it, evaluating it, in other words: the dream of being swallowed, digested, and spat out again, presumably dizzy, definitely shaken, thoroughly and utterly confused, as we re-enter the so-called real world?

Sverre Malling, "Flowers: Fritzl." 63 x 55 cm, 2013. Courtesy of the artist.

IV

I don’t know any work of art that incorporates such a multitude of grand-scale elements—architecture, ornament, sculpture, painting, illumination—and, at the same time, deals with emotional conflicts on such an intimate level. Mere speculation, of course, but I’m convinced that Vita reflects a variety of inner Vigelandian demons. Lust, envy, pain, pride, sorrow, remorse, joy, jealousy, ecstasy, horror, it’s all there, as one troubled man’s innermost dreams and nightmares take the form of a grandiose Gesamtkunstwerk.

The huge investment of personal anxiety into his work is what suggests, I think, the most plausible explanation for the radicalism of Vigeland’s imagery. I mean, newborns resting on a pile of skulls—or erect penises for that matter—must have been pretty out of the ordinary, to say the least, as subject matter for a fresco in the 1920s, ‘30s, and ‘40s, when it was made. At the same time, with regard to extenuating circumstances, Vigeland was obviously loyal to a solid tradition of monumental art, enough to be forgiven his excesses to a certain extent. In any case, this is what keeps his masterpiece fresh, rendering it no less beautiful and powerful in 2010 than it was by the time it was finished, Vigeland’s ability to cut to the bone of human behavior, regardless of time and place, the fight of—or for—our lives, so to speak, and thus unveil, through ruthless tableaus of existential extremes, the roots of both our deepest desires and our deepest fears.

V

“The violence of spasmodic joy lies deep in my heart,” Georges Bataille writes in The Tears of Eros, in what could have been an outline for the overall concept of Vigeland’s Vita:

This violence, at the same time, and I tremble as I say it, is the heart of death: it opens itself up in me! The ambiguity of this human life is really that of mad laughter and of sobbing tears. It comes from the difficulty of harmonizing reason’s calculations with these tears… With this horrible laugh…

As a visionary, Vigeland saw what Bataille saw, that the things which threaten our very existence and the things which keep us striving for more, are often one and the same thing. Where would we be, as sexual beings, without the knowledge of death? How strong would our passions be, separated from our fear of dying? We want to live, sure. But we want to die as well. We want to be torn apart. We want to drown in the wonders of ecstasy. And what work of art could possibly be worth studying that doesn’t, like Vigeland’s Vita—by evoking these antagonisms of life—bring us to the brink of tears?

Bataille:

In the violence of the overcoming [of reason], in the disorder of my laughter and my sobbing, in the excess of raptures that shatter me, I seize on the similarity between a horror and a voluptuousness that goes beyond me, between an ultimate pain and an unbearable joy!

Yes, I think it’s the intimacy of the Vita that both disturbs me and pleases me the most.

Bataille, had he seen it, would have been flabbergasted.

VI

As if a sort of visual excavation is taking place, the way the fresco gradually emerges as our eyes get used to the dark. And as the outside world disappears, like some already-forgotten fairytale, an inner world comes to life, constituting—from the moment of its revelation until the time we finally exit—our sole view of reality. While inside, we’re entombed, as is the painter. No escape, as day turns to night. And utterly astonished, as the fresco reveals, little by little, its myriad details, we accept our imprisonment with delight, lost in self-effacing contemplation, our eyes digging deeper and deeper into Vigeland’s visionary remains. For just as we lose sight of the outside world, we lose our grip on ourselves as well, forgetting who we are, in a perishing moment’s blissful infinity, as if absorbed by this wailing wall, becoming, willingly and reluctantly, participants in its orgy of eternal struggle.

VII

“I is an other,” Rimbaud wrote in triumph to a former teacher of his upon discovering, at the age of sixteen, that he was a poet, launching the concept of a chaotic multitude of personalities, rather than a solid and stable I, as the foundation—or absence of foundation—essential to any poetic creativity. And if we imagine these principals of creativity in reverse, the same rules applying to the experience of art as to the making of it, we would see that in order to fully appreciate the work at hand, we have to let go of ourselves as individual beings, thereby, at least for a short while, allowing a stranger’s paradise—or hell, if you like—to possess us, to become us, fully and completely.

Art teaches people to become someone else. Or at least, at its most powerful, it opens an abyss in people’s notion of who they are. It brings out the otherness in us, simply by preparing us to share, as we say, somebody else’s fate, to the point of taking on their identity as our own.

Eventually, all of us is an other. Or we possess the ability to be so, if pushed far enough. It’s a lovely and frightening idea, the dissolution of the I as its ultimate fulfillment. We are rent asunder, we lose ourselves, and then regain ourselves, for the sake of losing ourselves once again.

Sverre Malling, "St. George: Beachy Head." 63 x 55cm, 2013. Courtesy of the artist.

VIII

In the end, crying is all that matters.

Tears flowing, that’s the only worthwhile state in which to finish a book, or watch the end credits of a movie, or reach out for the repeat button on the CD player. Through this salty liquid, produced by our own bodies, we dissolve as individual beings and make contact with something greater than ourselves. It is one of our deepest needs, to be lifted above ourselves and thrown, by force, into a limitless, and therefore self-destructive, communion with something that exists as much within us as outside of us, unattainable save for in certain extremely emotional moments.

It’s what one might call a sacred experience.

Be it through art or sex or drugs, it’s the closest we get to Heaven.

It’s when the dam within us bursts.

It’s everything we dreaded and hoped for.

It’s nothing, really.

And nothing is why we came here.

And nothing is what we so awkwardly strive and fight for.

It’s the goal of all achievements, though we hardly ever dare pursue it.

It’s the prayer we direct toward any great work of art: God, take this pain away, which is me.

Stig Sæterbakken (1966–2012) was one of Norway's most acclaimed contemporary writers. His novels include Through the Night, Siamese, and Self-Control, all of which are published in English by Dalkey Archive Press.

Banner image: Detail from Sverre Malling's "Souvenir." 44 x 69 cm, 2011. Courtesy of the artist.