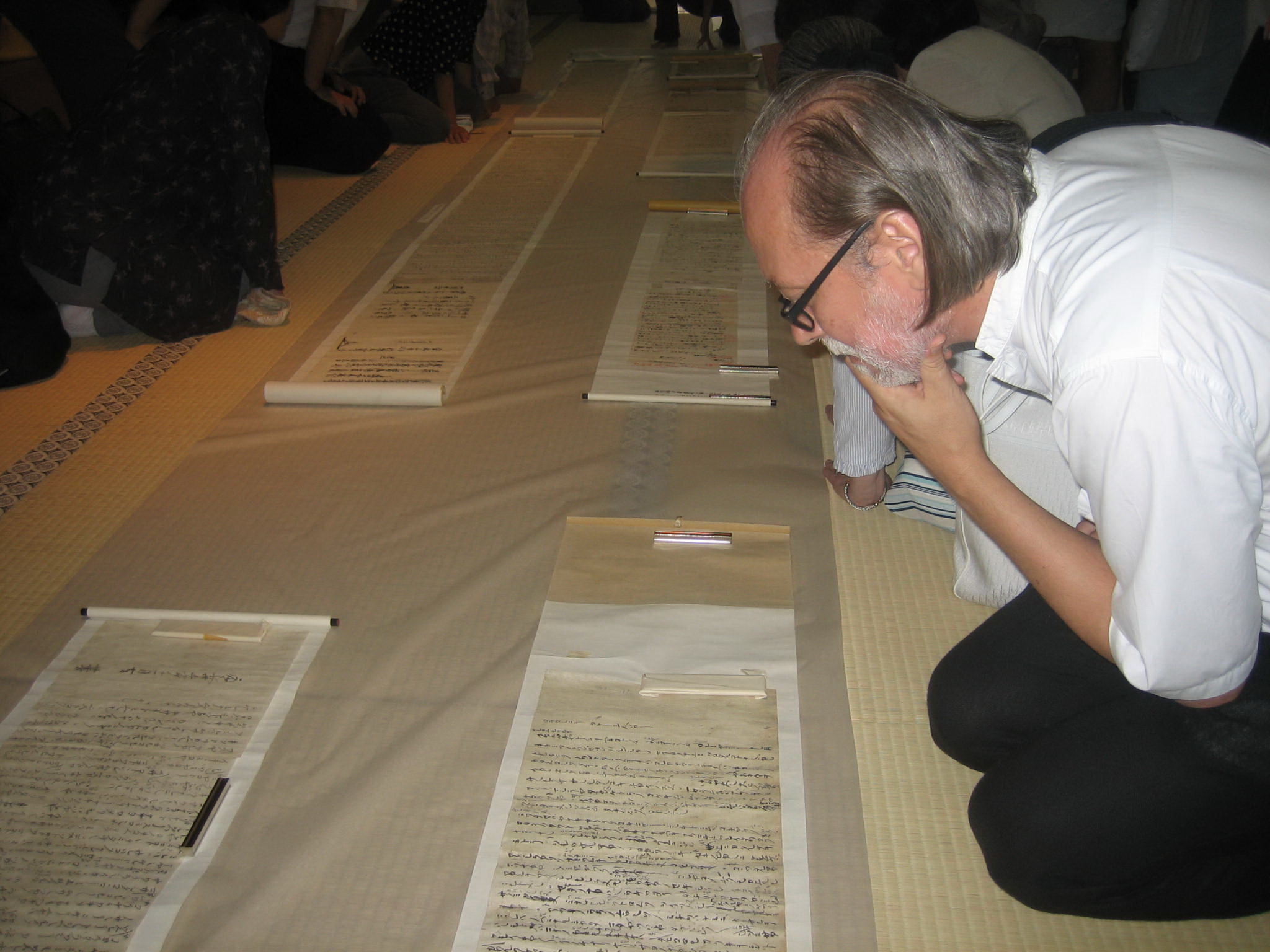

Arriving on the heels of widespread acclaim for his novel Satantango, László Krasznahorkai's 2014 Best Translated Book Award for Seiobo There Below—presented in Ottilie Mulzet's expert translation—serves to cement the Hungarian's status as one of the most original writers on the modern world stage. And yet, as welcome and celebrated as his work has been, only a portion of Krasznahorkai's extensive catalog is currently available to Anglophone readers. Now, Paul Kerschen delivers a masterful reading of the award-winning Seiobo There Below and offers a glimpse of what awaits us in coming years, including Destruction and Sorrow beneath the Heavens (forthcoming from Seagull Books in Ottilie Mulzet's rendering), The Prisoner of Urga, and Krasznahorkai's debut short-story collection, Relations of Grace. This essay, originally published in Music & Literature No. 2, is accompanied here by a series of photographs documenting the author's encounter, organized by Osaka University and held at the temple of Hōzan-ji, with the original manuscripts of the fourteenth-century Japanese actor and Noh playwright Ze'ami, whose spirit infuses Seiobo There Below, and whose influence is felt throughout much of Krasznahorkai's as-yet-untranslated oeuvre.

The god: now this role has the look of the demonic.

—Ze’ami, Performance Notes

Some writers are intellectual wanderers, taking on a new theme with each new book. Others are fixed stars. László Krasznahorkai is very clearly one of those who discovered his particular obsessions early on, and who has since kept faith with those obsessions by writing the same book again and again in different guises. But this repeated book is not easy to characterize. For readers in English, Krasznahorkai is the author of Satantango, The Melancholy of Resistance, and War and War: the “Hungarian master of the apocalypse,” in Susan Sontag’s phrase, who works to chronicle meager, rural lives under threat of annihilation. This picture is vivid, and accurate as far as it goes, but it does elide the books not yet available in English, which are, by and large, neither Hungarian nor apocalyptic in their subject matter. These books tend to be set abroad, most often in Asia, and might be described as works of devotion. Admittedly this devotion is a peculiar and perilous state; its objects are not persons but the impersonal beauties of culture, and it often brings the devotees to the brink of destruction. Krasznahorkai is not a sentimental writer. He is simply one of the most sincere writers living, with an utter conviction in the urgency of his themes. Among these themes are violence and decay, but none of his books—not even the supposedly apocalyptic ones—could be built from that material alone. Read in sequence, the continuities in his fictions loom much larger than their departures; each is recognizable as a stage in the repeating book, and each throws glancing light back on the others. From the beginning Krasznahorkai’s career has traced a cautious, eccentric arc around the possibility of heaven. It is a strange possibility, and can be illustrated only by example.

Photo: László Krasznahorkai

It begins in the eight short fictions collected under the title Relations of Grace (1986). These were written simultaneously with Satantango, and like many early stories they form a record of experiments, trying out different elements in combination. The long, ruminative paragraphs with unattributed quotes are familiar from Satantango, as are the decayed Hungarian settings, but what marks them most is their sympathy for the outsider. Their protagonists are uniformly opposed to the collective, often by way of violent crime; an especially memorable offender is Herman, the disgruntled gamekeeper who discovers a fellow-feeling for the predators that he is supposed to be trapping. But the outsider who most anticipates the later fiction is Pálnik, the retired schoolteacher of “The Signal Seeker.” His rebellion is simply to refuse the village secretary’s prolix, scrawled summons to civic events, and instead to stay home and tune in the capitals of Europe on his radio.

Let them say that “all he did was twiddle those damned knobs,” he knew: this was what instantly released him from his squeezed-in state at the end of the world, from his pressing isolation, into a spaciousness where the pitiful screeching of the villagers couldn’t force its way in, where there was no longer a reek of “carrion stink” descending like fog, from where, coolly looking back, one could make out nothing of the earthly world but: it is possible.

In this state Pálnik reaches insights both exhilarating and doubtful: “Inspired by the knowledge he had attained of radio waves, he suddenly hit upon the unprovable conjecture that God, for us, is perhaps an unapproachable, incomprehensible and extraordinary configuration of space, the rarest, an ‘absolutely rare’ structure, a spatial case, for us nothing.”

Photo: László Krasznahorkai

The word kegyelem in the collection’s Hungarian title can mean a juridical pardon, or else theological grace: in either sense an unwarranted gift. Pálnik’s gift of visions makes him into an early version of the type that will become Valuska in The Melancholy of Resistance and Korin in War and War. If this early character does not attain their full depth, that is in part because of the story structure he inhabits. Compared to the later work, these early pieces deal with their outsiders in conventional ways. They die, or are condemned, or are made to repent their solitude. The one outlier is the remarkable “The Last Boat,” which takes the collective as protagonist. Narrated in the first person plural, it depicts the last sixty inhabitants of an abandoned city, apparently Budapest, departing under armed guard. In place of any explanation or forecast, the story lingers on historically resonant details: hastily packed belongings, queues with identity papers, the confusion of arriving and departing authorities. This open structure is a great advantage, so much so that it will become a central feature of the novels; together with the visionary outsider and the intimation of collective disaster, it forms the seed from which both the Hungarian and the Asian narratives spring. In the Hungarian fictions, the visions and the disasters come together; to look past everyday reality is to be ripped apart. The Asian books are more ambiguous. In these the vision is sought out purposely, in hope of solace, and the visionary will survive to tell his tale, since he is the author himself, or at any rate a ready-to-hand fictional version. That is to say, these are pilgrimage narratives.

Photo: László Krasznahorkai

In The Prisoner of Urga (1992), a character who shares his author’s name and temperament takes the Trans-Siberian Railway through Mongolia to Beijing. The occasion for the trip is a spiritual crisis of Dantean proportions (the book opens with the first tercet of the Divine Comedy), impelling a journey through hell and heaven, not necessarily in that order. On his first night in Beijing the narrator looks up at the stars, like Dante climbing out of Hell, and contemplates the “very deep questions” that have driven him forth. But the longer these questions are contemplated, the murkier they become, until the narrator is brought round to admit that they are worse than unanswerable; they are simply incomprehensible. Even to gesture at them is “impossible as—for example—to say of an enormous shark that has just dived down and escaped into the deep, hey, where’d it go, while sitting on the beach and straining one’s eyes over the heaving mass of the ocean.”

Thus the pilgrimage begins with a humbling. Many more will follow; the next order of business is to catch a bus. The book keeps one foot in modernist abstraction and the other in the mundane details of transit, a shift in register that would be jarring were it not that thinking, for Krasznahorkai, is so much like traveling through a foreign country. One labors under the same uncertainties, the same disorientations and falsifying of assumptions, and after a few pages of following the narrator down a Beijing sidewalk as he helplessly tries to distinguish bus 44 from bus 403, one is quite ready to accept the larger parallel. A later scene, in which he attempts to bribe a station employee with the thirteen travel clocks and seven cigarette lighters that an acquaintance had advised him to pack, is not only very funny, it brings specificity to a travel narrative that might otherwise drift into parable.

Unquestionably, there is something here of Kafka’s China, the realm so vast that no message can traverse it. A rail journey through the Gobi desert, a space so empty of landmarks that it renders maps and timepieces useless, brings home the horrifying truth that “the eternal is indeed a reality, but for us a nightmarish and forbidding reality, that eternity is indeed the province of the gods, but these gods are frozen, unapproachable, cold and hellish, that eternity is nothing more than a total, fatal symmetry heated to the point of madness.” This follows not only the sentiment but the exact phrasing of the Hungarian fictions. Pálnik too describes the divine as unapproachable (megközelíthetetlen), and War and War contemplates a reality examined “to the point of madness” (őrületig—that is, madness in the terminative case). Like Korin, who believes himself possessed by Hermes, this narrator cannot quell his interpretive drive; everything is a portent. In Guangzhou he nearly dies of a perforated lung and spends a week in bed listening to the half-step drone of the bedside air conditioner and—to his utter shock—inwardly entrusting his life to the Christian God. The questions driving his pilgrimage may be formless, but their answer, it becomes clear, must take the form of a divine encounter, however figurative or fleeting. Cautiously and yearningly, the narrator sums up the fruit of his journey as “the wondrous conviction of the possibility of contact with the gods…the fragile, butterfly-light belief that there do exist divine and ideal heights over the hellish vision of human lowlands.”

Photo: László Krasznahorkai

What is unclear is whether this salvational dream can be separated from the unapproachable, maddening nature of the divine. It would take a Dante to answer this conclusively, and Krasznahorkai, an exceptionally inconclusive author, does not try. Instead he narrows the scope: if any such contact is possible, he implies, it must come through the medium of art. The heavenly vision that the narrator would place above hell appears at a performance of Peking opera. Overwhelmed by its conviction and aesthetic exactitude, he comes to believe that these are not actors—that this formal discipline and beauty have opened an actual passage into a higher realm. “What sort of play is this before me, I wondered. What sort of power is playing with me? What enchanted realm?…and then a young girl stepped onstage, of such beauty as no one has ever seen, nor will ever see.” The girl’s appearance is the high point of the vision, but also an opportunity for deflation, since she occasions the most obviously fictional episode in the book: the story of a besotted Krasznahorkai going on to write her scores of letters after the performance. Her epistolary response takes up a chapter of its own, and gives a stern warning of the distance between heaven and earth.

In the narrator’s final, most serious trial, a rail delay strands him in the Mongolian capital. The historical name “Urga” is used in part because the year is 1990, and street protestors are demanding that the Communist-era “Ulan Bator” be retired; but it also indicates a narrator terrified by history. In the national museum he discovers an exhibit of torture devices from the Mongol empire, complete with depicted dismemberings, burnings, blindings and crushed skulls, and foresees the coming of a new Middle Ages. Faces on the Urga streets glare after Russians—every European is a Russian here—and are said to form drunken mobs after dark. Barricaded in his room, staring out the window at Soviet-style buildings and wrecked Volga automobiles, the narrator witnesses a peculiarly disturbing scene: two schoolchildren stagger against the wind, carrying leather satchels of exactly the same make that he carried in his own Hungarian childhood. There is no attempt to discursively explain the power of this image. As a personal token of the vanished Soviet empire, it suffices to show that “Urga seizes you at the most sensitive point precisely in order to convince you that hell does exist, and that between the heavenly and the hellish there is not the slightest correspondence.”

It is tempting to say that this simply runs Dante backward. If the medieval pilgrim passes through hell as a preparation for heaven, the modern pilgrim, presumably, glimpses heaven only to have it shattered by hell. But this seems too final a judgment for so ambiguous a book. If heaven and hell cannot be brought into correspondence, they nonetheless appear in the same narrative, and it may be that if nothing else survives the journey out of Urga, the narrative itself will have to stand surrogate.

Photo: Kayoko Takata

It is an older writer, less driven by personal crisis and more at ease in the world, who returns to China in Destruction and Sorrow beneath the Heavens (2004). In the intervening years, we are told, he has radically changed his mode of life. He now lives and works in a remote mountain village, which has deeply altered his approach to his art: “I always find it too rough, too crude, I must constantly refine it, moderate it to an infinite degree.”

He is now well read in classical China, at least by European standards. He knows, for instance, that outside the city of Zhenjiang one finds the Jiangtian monastery with its “First Lifespring Under Heaven,” in the Tang era a renowned source of water for tea. What he does not know ahead of time, and cannot know until he reaches the spot, is that this lifespring us now a filthy pond enclosed by a hideous wall of fake marble and, across the river, a plastic playground of Disney characters. The entire Jiangtian complex has turned into

a safari park, where nothing is genuine, where everything must be paid for, it turns out that all the buildings here are brand new and fake, that all the Lohans and so-called Buddhas and Bodhisattvas are brand new and fake, that every groove and every pillar and every inch of gold paint is brand new and fake, that everything is a fraud, wherever you turn you meet a salesman dressed as a Buddhist monk, in almost every corner of the temple some horrible pious trash is being sold…

The famous canal village of Zhouzhang, with its rows of picturesque houses along the water, seems perfectly preserved from Ming or Qing times—at least for the span of one night. At first light the next morning a pack of tourist buses descends, transforming the houses into a gallery of shops selling sweets, jewelry, postcards, compact discs, and the narrator is driven back into the wilderness.

The tian xia of Confucian thought imagines the world as an ordered harmony “under heaven,” with the Chinese state and imperial court at center. Destruction and Sorrow beneath the Heavens is a protest against the destruction of that order, begun under Mao and finished off by what the narrator calls ÚjKína or “New China,” the fruit of global capitalism and the tourist industry. To visit a foreign place, draw a distinction between tradition and modernity, and execrate the latter is of course a risky strategy, simply because it is so conventional; it can’t transcend the paradox of tourism, that each visitor resents all the others for polluting his particular experience. The narrator’s reverence for classical China can stretch credibility, as when he says that Confucianism is “the only social philosophy which has introduced morality into everyday life, into human life.” One recalls a long history of Westerners who have seen in China what they wished to see. Yet having the narrator tip his hand in this way is revealing, since it suggests that despite his constant disappointment, the pilgrim cannot give up hope of contact between the human and divine; indeed, that if Krasznahorkai the author were definitively to give up this hope, there would be no more books. Asian religions have their upper and lower realms, but they are not quite the impassable dualisms of Christianity. Correspondence between heaven and earth is at the center of Confucian thought; more mystically, the Mahayana tradition takes Buddha-nature as latent in all beings. Like his modernist predecessors, Krasznahorkai is interested in abstractions, but he locates his particular interest at their points of friction, where they abut onto concrete reality. The Melancholy of Resistance stages this encounter at its most tragic; the travelogue reprises it as grim comedy. A pilgrim goes to China seeking enlightenment, and discovers a theme park.

What most distinguishes Krasznahorkai’s treatment from others on the subject is the naked insistence of his prose. He is not shy with superlatives, nor with repetition. The book opens with the lament that “there is nothing more hopeless in this world than the so-called Southwest Regional Bus Station in Nanking,” but right away it finds further candidates:

there is nothing more hopeless than these streets, than the interminable rows of barrack buildings on both sides, frozen in eternal temporariness, for there are no words to describe the hopeless colors, the slowly killing varieties of brown and gray…we are bounced and shaken in this continually denser, indescribable haze of brown and gray, inside which it seems wholly incredible that anything outside this fearsomely empty mixture of brown and gray exists at all…

As with the “very deep questions” in The Prisoner of Urga, the repetition is not simply an intensifier. It also creates a subtle estrangement effect, holding up the phrasing itself for inspection. To say that the narrator is unreliable would be too crude. But Krasznahorkai’s syntax can produce not only an immersion in the process of thought, but also a distancing. In interviews he has described his protagonists as “narrators behind the book. I myself am silent, utterly silent in fact…the sentences in question are really not mine but are uttered by those in whom some wild desire is working.” This is the case even when the protagonist is named László. The book takes its epigraph from Yan Fu’s scholarly notes on Montesquieu: “The use of the first person singular does not mean: I.” Destruction and Sorrow beneath the Heavens holds the first person at sufficient remove to work as a study not only of modern China, but also of the sort of person who would seek wisdom there.

Photo: László Krasznahorkai

Still, this would be a tricky strategy to maintain over an entire book, and Krasznahorkai does not attempt it. Instead he devotes the later chapters to interviews with representative characters: an old woman who runs a boarding house, an urbane gentleman described as “the last Mandarin,” writers and cultural officials. Though we read the transcribed responses at a remove (they come either through an interpreter, or else in lingua-franca English before being set down in Hungarian), they open a much-needed aperture in the narrator’s thoughts. They are always anecdotally interesting; at times they push back against the narrator’s advocacy of Confucius; and very occasionally they open into the kind of philosophical encounter that is the stated object of the journey. In the Suzhou gardens a gray-haired sage discourses on simplicity and emptiness in art, and puts his program into practice with a page of writing that the interpreter can render only as disconnected characters: “Buddhism / not at all pessimistic / against death / each defeated / zither, chess, calligraphy, painting.”

The strongest points in the book are its enigmas. Once again the Chinese bus system furnishes good material. A woman is picked up the freezing rain at an unmarked point in the country, without any prior signal, and the narrator reflects that “this is only one of many rules, unknown to us but still functioning, merely a tiny fraction of an entire system on which we rely and which somehow persists so that this bus here and all the other buses can continue their routes through China, of which there are millions, every day, and every morning and evening, and every afternoon and forenoon.” We are back within Kafka’s infinite, inscrutable China, and this vertigo extends itself to the new passenger, who cannot, the narrator thinks, be differentiated from “immeasurable and undefinable mass of people” around her. As she takes her seat, cheap clothes dripping, he “couldn’t say who had sat down, because anyone at all could have sat down, this woman could have been anyone at all, this woman—and here was the most pitiless of all truths and the most pitiless of all facts—made no difference.” Following which the unremarkable person does something remarkable: she pulls open the bus window so that the wind and rain can continue to pelt her. The conclusion of the story is too good to give away; it both resolves and deepens the mystery, and sends a parting message that what is most likely to cross cultural barriers is the sense that life everywhere is equally strange.

Photo: László Krasznahorkai

Seiobo, or The Queen Mother of the West, is a fifteenth-century Japanese play with minimal action even by the standards of Noh theater. It belongs to the category of kami-nō or god plays, in which a deity appears first in disguise and then in full splendor, and so carefully restricts itself to this moment of appearance as to exclude anything in the way of character portrait or dramatic conflict. The plot reenacts a single moment in mythical time: the descent of the goddess Seiobo (the Japanese version of Xi Wangmu, a Chinese immortal) from her heaven to the court of the Emperor Mu, bearing in her hands the fruit of immortality. This is not drama but staged ritual; all its craft is directed to manifesting the sacred.

Krasznahorkai’s most recent large fiction, titled Seiobo There Below, includes a first-person set piece narrated either by the actor portraying Seiobo in a Noh performance, or else by the goddess herself. All the theater’s devices—costume sword and phoenix crown, flute and drums, dance steps, chanted poetry—stand at her service to communicate “that there is a Heaven, that high above the clouds there is a Light which then scatters into a thousand colors, that there is, if he [the Emperor] casts his gaze up high and becomes deeply immersed in his soul, a boundless space in which there is nothing, but nothing at all, not even a tiny little moment…” As in The Prisoner of Urga, heaven is evoked only to be swept away. After her declaration Seiobo returns to her sphere of nonbeing, “for that is the place where I exist, although I am not, for this is where I may place my crown upon my head, and I can think to myself that Seiobo was there below.”

Seventeen such meditations on art make up this book, passing from Achaemenid Persia through fifteenth-century Italy to the museums and shrines of modern Europe and Japan. If this is a novel it pushes the limits of the form, since there is no continuity of character or plot between sections; yet the thematic recurrences are too strong to suggest a division into separate stories. The best analogy for a work so concerned with reception and restoration might be that of a meticulously curated museum exhibition, in which heterogeneous pieces are arranged for cumulative effect. One obvious sign of additive intent is that sections are numbered by the Fibonacci sequence. It is not only the components of this books that are being summed up, but previous books as well; the cultural span of the travel narratives meets the oblique structure of the fictions, and the pilgrimage theme that unites them. Many sections take an errant Hungarian character as focal point, sometimes a tourist like the Krasznahorkai of the travelogues, sometimes a more maddened figure recalling Valuska or Korin. In part this reprises the old Romantic tenet that art at its most powerful is given to outcasts. But it also implies a still older belief in art as a manifestation of the divine, and so far as this belief is taken seriously, it credits the artwork with overwhelming power.

Photo: Kayoko Takata

At its most benign this power simply perturbs characters into eccentric orbits. A retired architect’s passion for Baroque music finds outlet in a lecture (“A Century and a Half in Heaven”) given at a provincial Hungarian library. His encomium to that lost age of inspiration is laced with sideswipes at Mozart (“this genius of pleasantness?!—the charm of this undoubtedly amazing showman?!”) and a detailed guide to recording artists (“the airy Bartoli NO, but Kirkby YES, then the enfeebled Magdalena Kožená NO, but Dawn Upshaw YES”)—none of which edifies the audience of six old women and two old men, who grow increasingly desperate for the lecture to end. Another incorrigible apostle is the Louvre museum guard who desires only to watch over the Venus de Milo for eight hours every day. For the afterhours he has pasted countless reproductions of the statue on his bedroom wall (“well so what is the problem if I find that which is beautiful to be beautiful, he posed the question…”). Other pilgrims are ill-starred. A Hungarian drifter washed up at a Barcelona museum meets a reproduction of a Rublev icon and is shattered: “and almost immediately at the sight he collapsed, for he knew right away, as he looked at them, that these angels were real.” To encounter the divine in any form is terrible. The devoted architect asks, “…how could we even imagine that it is even possible to traverse that distance where music exists, and not be annihilated one hundred, one thousand times—I am in a thousand tiny pieces, if I listen to them…” Some characters are able to cordon off this shattering in the realm of metaphor; others are not. Like all of the pilgrims, the Barcelona drifter is in some sense an innocent. But the dangerous—even lethal—quality of innocence has been one of Krasznahorkai’s messages since Satantango, and this character in particular takes a desperate turn.

In its historical scope, and in its relation to bodies of specialized knowledge, Seiobo There Below has points in common with the Anglo-American encyclopedic novel. But where a writer like Thomas Pynchon (whom Krasznahorkai admires, and credits in his epigraph) will use informational glut as noise, to be layered over a text until novelistic form vanishes, Krasznahorkai prefers to take a handful of facts and meditate on them. This sense of a concentrating mind gives the writing a more novelistic feel, even when the mind in question is not attached to any particular character. The story of the museum guard includes a summary of the Venus de Milo’s contested attribution, originally to Praxiteles and later to the Hellenistic era, while the story of the Barcelona drifter comes together with a history of Russian icon painting. In neither case is this information in any sense narrated by the pilgrim. Yet it is colored by the pilgrim’s depth of emotion, and this gives the writing a very different cadence from pure reportage. (As Wallace Stevens said of Marianne Moore’s factual poem on the ostrich, “Somehow, there is a difference between Miss Moore’s bird and the bird of the Encyclopaedia.”) This is true even of those sections that have no fictional pilgrim and might well be classed as essays. A treatise on the Alhambra, factual from beginning to end, is nonetheless driven by obsessional unease with a monument whose precise purpose is unknown and which seems to stand for nothing other than itself.

The book acknowledges both scholarly pedantry and Romantic Schwärmerei as responses to art. But it succumbs to neither, and finds the best balance between them in concentrated devotion to a craft. This is most evident in the Japanese sections, which take artists as their protagonists, along with other initiates in transience and patience. Ze'ami, the perfecter of Noh form who may have written the original Seiobo play, believed that the most truly masterful performer is one who allows conscious intent to fall away while performing. “Forget about the actor,” he advised, “and watch the mind. Forget about the mind and know the performance.” Though Krasznahorkai’s sentences seem the opposite of Zen brevity, their concentrative quality turns out to be an excellent match for this immersive state. The subject of an artist at work meets the style, one might say, at its most sane. There is palpable solace in the many patient pages that follow conservators restoring a Buddha statue, the abbot who leads the ceremonies for its removal and replacement, the ritual apparatus of rebuilding the Ise shrine every twenty years. The artists themselves, naturally, are not untroubled. The carver of a Nō mask finds his workshop

at the very least such a life-threatening perilous labyrinth, where in every single movement of every single phase of the work there exists the possibility of error, beginning with the question of whether he picked out the correct piece of wood at Okari-san’s, whether he ascertained correctly the line-structure of the hinoki, for one must know with utter certainty where the individual lines are placed in the tree, because everything, but everything has to be determined on the basis of these lines, this decides the location of the central axis, and through that every single line to be drawn from the stencils, but then comes the drawing of the contours, the decision as to where the tip of the nose will be, then the eyebrows, the forehead, the lower nostrils of the nose, the depth of the chin, and the ear, he cannot err in any single moment with any single stroke of the chisel…

Photo: Kayoko Takata

Both author and character understand the stakes of failure. But both also have technique at their disposal, and are able to lose themselves in technique so completely that it comes as a genuine surprise to find that the mask is finished and the carver has created a monster: “and he doesn’t even suspect, the thought never even occurs to him, that in the space of hardly more than a month and a half, what his hands have brought into the world is a demon, and that it will do harm.”

Seiobo There Below never strays from the conviction that all things tend to ruin. Its last section travels back to the edge of history in China’s Shang dynasty, a period known only from legends and a handful of archaeological sites. Beneath these sites tomb guardians are buried, bulging-eyed beasts “screaming beneath the earth” to remind us of death, and of the certainty that they will survive us. Such a conclusion, and indeed such a book, will probably do little to change Krasznahorkai’s reputation as an apocalyptic writer. Yet he refuses the most tempting promise of the apocalypse: that it will bring about an unveiling, that what we see now through a glass will appear face to face. Truly apocalyptic fictions, from John of Patmos forward, tend to come with moral categories clearly drawn. Krasznahorkai’s characters may long for that clarity, no less than they fear the attendant destruction, but to judge the living and the dead is not the author’s business. Likewise, as important a role as art plays in these books, it would be wrong to call that role redemptive. A redemption implies an eschatology, and again, such a transaction is foreign to a fictional world where nothing concludes for good. Art is the solace we have while our days last, and that is all. Or else it is the veil behind which the gods move. But though that veil shimmers, it cannot be lifted. The pilgrim stays on the road.

Paul Kerschen is author of The Drowned Library. He studied and taught at the University of Iowa and the University of California-Berkeley, and now writes and develops software in California.