One of contemporary American fiction’s most lauded and prolific novelists, Richard Powers might also be described as the autodidact’s autodidact. An amateur musician and composer, former physicist, and self-taught computer programmer, Powers has become known for his deftness at tracing out the subtle interrelationships between science, art, and politics with a lyrical virtuosity and breadth of intelligence that have elicited comparisons to writers from Melville to Whitman to David Foster Wallace.

In his most recent novel, Orfeo (2014), Powers examines the post-9/11 political landscape through the life of avant-garde composer turned amateur chemist Peter Els, whose Orphic descent into the underworld of twentieth-century composition and lifelong fascination with patterns lead him to attempt encoding music into the DNA of a living organism. After his makeshift home microbiology lab suddenly attracts the attention of homeland security, Peter Els is forced to flee, paying final visits to his loved ones and friends as he develops a plan to turn his run-in with the security state into his greatest work of art.

The third of his novels to use music as a centerpiece (after The Time of Our Singing and The Gold Bug Variations), Orfeo is yet more evidence of Powers’s rare gift for articulating the seemingly ineffable qualities of sound, one that is accompanied by a near-encyclopedic knowledge of music history. Incredibly kind and generous, Powers spoke with me via Skype about his new novel and how music factors into his vision.

—Keenan McCracken

I. PRECISELY THE THING THAT WORDS CAN’T GET TO

Keenan McCracken: From what I understand you’re a musician and a composer yourself. Did you ever think of pursuing either as a career?

Richard Powers: Well, I always thought I was going to be a scientist. I studied a few different instruments growing up. I sang in several groups when I was very young. I studied cello as a boy prior to moving to Bangkok. In Bangkok, the climate was pretty difficult on string instruments, so at that time I switched to reed instruments and I played clarinet and saxophone. When I returned to the States as a teenager, I took up the cello again and played that extensively through high school and college. Music was a great love, and it accompanied me at every turn on that journey. I did briefly consider giving my life to it. But then, words started calling. Ultimately, though, I’ve been lucky enough to have it both ways: a life writing novels, and among those, several novels about the lives of musicians!

KM: Did you know early on as a novelist that you would eventually like to have music play such a crucial role in your work?

RP: Well it’s interesting. I don’t think I was conscious of it, of music being an explicit organizing theme of my fiction, until my third book. It played a role—a significant role, I think—both in structuring and also to a lesser extent in subject matter in my first two novels. So it’s revealing for me now after eleven novels, including three books dedicated to a foreground exploration of music in different guises, to go back to those early works and see the evidence—to see the way in which music would come back to dominate the books and become a lifelong obsession.

KM: Was it daunting to start writing about music, trying to touch upon its effect on people through writing fiction?

RP: It’s something that creative writing teachers and those who expound on fiction traditionally warn writers against trying to do. Music is supposed to be so primal and to go so much deeper and farther than words that any attempt to translate it into words can only reduce or diminish it. I don’t know why I didn’t take that advice early on or why that prohibition never made sense for me. Maybe it was partly because I’m the kind of musician and the kind of listener who experiences music, if not as a language, than at least as an information-rich, linguistic phenomenon. You can listen to music for millions of different reasons, and if you consider the fundamental components of music—melody, harmony, rhythm, texture, timbre, form—there are styles of listening that emphasize each of those.

For many people the primacy of texture and timbre in music would make any attempt to incorporate it into a narrative, into a verbal construction, a little bit pointless. These listeners go to music precisely for the thing that words and verbal semantics can’t get to.

Other people who are attracted primarily by harmony and the progressions of harmony probably feel more affinity with the prosody of words and the meanings encapsulated in the syntax of sentences and the changing progressions of chunks of story. That sense of a lingering unfolding of expectation, followed by surprise or satisfaction in moving away from or toward those expectations, is shared across those elements of music and prose. My love of harmonic expectation and progression in music is not unlike my love of cadence and register in prose. I don’t always read for story or character. I often read for language and for the unfolding trajectories of sentences and paragraphs. And it never really felt profoundly odd to me–once I did commit in my third novel, The Gold Bug Variations, to writing about music—to explore the common features between prose and sound, pure musical sound.

My other answer to that question has to do not just with taking music as an organizing principle or approach or set of concerns, but with using music itself as the primary subject matter of a novel. I did that with the three novels that are called my music books. In those novels, I tried not just to put into words the effect of sound on makers and listeners but also to depict music as a cultural activity, as a social act, an historical act, a political act, and to use music not just as the window dressing, the color, of the story but for the story matter itself. In the same way that novels can be about who’s up and who’s down, who’s in and who’s out, who loves whom, who gets to marry whom, they can also be about the changing nature of the use of music as a cultural commodity—about who gets to sing what and why, and about how we fashion ourselves through the act of making music—fashion our identities, fashion our social allegiances and political alliances. Those themes became increasingly important to me as I ventured into those musical novels.

II. THE MOST FAMILIAR PIECE OF MUSIC CAN SUDDENLY GO STRANGE AND DANGEROUS

KM: There’s a lot of thought dedicated in your work to the colliding of the musical and the political, musicians who both confront and are confronted by political reality . . .

RP: That’s right. When music itself becomes the subject of a novel, then the characters begin to choose and fight over the stakes of what music means. You know I’m also a writer who has devoted many books to the exploration of science as a social phenomenon, and as psychological and political phenomena, and I’ve often tried to distinguish my novels from ones where science is a kind of stage setting for stories that are essentially about other concerns and other stakes and other contests—personal contests for which science is merely incidental. In such novels, we know so-and-so is a scientist because he’s wearing a white lab coat and there’s a test tube bubbling away behind him. Instead of that, I wanted to say what was in that bubbling test tube and to promote the test tube itself and its contents into characters in the story, to give the test tube valences and to show how what the human characters do to each other is very much interconnected with their actual preoccupations in the scientific world. And I would say the same for my interest in fictionalizing music. There are many, many novels that use music as an incidental stage setting for a story, but there are fewer novels that promote music and musical pieces to the role of character or actor inside the story, where the actual music being made and the issues, the alliances, and the stakes of making that particular kind of music become important to the story. That’s what I was really after in these three books.

KM: Is that partially what motivated you to write about Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time so thoroughly in Orfeo? You’re describing the experiencing of creating, performing, and listening to music almost in real time, as well as looking at the political conditions under which it came to being . . .

RP: That’s a great example of the promotion of music to an actual participant inside the story. In a traditional novel—a well-behaved novel—once you start telling the story about your protagonists in the present, you might briefly stop the forward motion of that story to give a little bit of a backstory, and that incidental stage-setting might take a paragraph or two or even a couple of pages, which would be a long aside. In Orfeo, the ostensible story of Peter Els—this seventy-one-year-old composer who falls afoul of the law—stops, and this seemingly unrelated story set in a prisoner of war camp in 1941 completely interrupts the forward motion of the central narrative of the novel, then goes on for pages and pages, re-focalized through the camp prisoners and narrated through their point of view at great length, and it’s not immediately clear how this is furthering the cause of the drama, the story of Peter Els. It only becomes clear at the conclusion of this many-page set piece how that experience—the historical origins of that piece and the stakes of that music, in its unique conjunction of aesthetics and politics—is of direct urgency to Peter Els and his understanding of his own life. When you reenter the contemporary story and you understand that this is the piece that he’s been teaching to a group of elderly people in a nursing home in a continuing education course, what you just read gets recontextualized, and the music becomes a different kind of phenomenon. That interaction—between past and present, between production and consumption, between the historical conditions of a work and the way that piece is heard in the present by people who aren’t particularly musically sophisticated—changes Messiaen’s somewhat difficult and esoteric notes into something with new significance, something in the listeners’ own stories. My desire in Orfeo was to recontextualize music in a variety of ways: as historical narratives, as a set of manifestos, as personal documents. I wanted to describe the way that music is made, fought over, listened to, neglected and revised, and to try to find as many different ways of bringing actual pieces of music into a fictional story. It helped to have this bridge mapped out between the fictional world of characters and imagined narrative conflicts, on the one hand, and the factual world of twentieth-century avant-garde music as it has been contested in the real world, on the other. The desire to find a form that passes between the imaginative and the actual, between the aesthetic and the political, the invented and the historically documented and distributed—that desire drives me as a novelist.

KM: Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony is similarly given an extensive description in the book, a piece that was composed under Stalin’s rule and is a perfect example of that conjunction of the aesthetic and the political. Is that a kind of dream piece for Peter Els, one that visibly moves the audience yet manages to be politically subversive?

RP: Yes. The story of this piece is well known in musical circles and is incredibly resonant. The Fifth was Shostakovich’s first major public composition following the enormously provocative public slap-down by Stalin over his opera Lady Macbeth. Shostakovich was writing to save his own life without losing his soul. He was trying to compose something that would seem to be a public retraction while still being personally defiant. He had to get off the death list, while still writing music he believed to be true, and this incredible drama, this confrontation between Stalin, the engineer of human souls, and Shostakovich, the subversive music maker—the creation of this marvelously ambiguous piece that can be heard in so many ways—is a supremely dramatic story. But that textbook example of the twentieth-century artist’s crisis—the battle between surviving and rebelling against the totalitarian state—becomes something else again when my composer listens to it on a CD in a car fleeing westward just after having his own run-in with the security state. Els himself is now a fugitive, not through any deliberate act of political subversion on his part, but through a tragicomic misunderstanding, a mishearing. For Els to hear Shostakovich’s Fifth again when his own life is now on the line changes that old warhorse piece that he has listened to hundreds of times in his life into something newly uncertain and volatile and explosive. Even the most familiar piece of music can suddenly go strange and dangerous, when life changes the terms of hearing.

KM: Was examining in Orfeo the post-9/11 political landscape and the culture of fear through the life of an avant-garde composer a way of also getting at the danger of art then?

RP: You know, that’s a wonderful synopsis of my preoccupation in the book. Peter Els’s life from the moment of his birth in 1941 through his early old age is a preoccupation with music as a disturbing force, music as a troublesome, provocative, potentially subversive form of expression. His life is given over to this dance with difficult music, this search for a kind of structured sound that the ear doesn’t know how to hear yet. And because he strives to write a kind of music that pushes forward, through a difficult vocabulary, into possibilities for expression that haven’t yet been explored, he ends up running up again and again against a fear of culture. His audiences are frightened or antagonized or hostile toward his mode of expression. It isn’t until he begins this somewhat mad attempt to find the ultimate avant-garde gesture—to write music into the chromosome of a living cell—that he triggers his own explosive confrontation with the broader public. So his lifelong attempt to trouble the ear into hearing finds another audience—Homeland Security—and the constant fear of culture collides with the culture of fear. This relationship of art with danger infuses every aspect of Els’s story.

III. A KIND OF WRESTLING WITH DEATH AND DARKNESS

KM: The title Orfeo is of course a reference to the Orpheus myth and the book makes use of that myth in an unconventional way. As an avant-garde composer Peter Els strikes me at times as kind of an anti-Orpheus. His music has no popular appeal and winds up playing a kind of destructive role in his life.

RP: Well, the Orpheus story itself raises the question of whether music is an innate, natural, and effortless efflorescence of beauty or whether it is a wrestling with something much darker. The seductive power of music to overwhelm, to inject deep, unmediated emotion directly into the central nervous system is part of the Orpheus myth. Orpheus can charm animals and make even the stones weep. But the other part of the Orpheus myth is Orpheus going down and dealing with Death, the king of the underworld, saying: I’m going to force you to release my muse. Els, too, makes this downward, dark journey that’s both a private attempt to go back into his past and retrieve his original muse—to get death to cough up all the hostages that it has taken in his life—and also part of the public, shared journey of music itself through America in the twentieth century.

The music of our time has been another kind of wrestling with death and darkness, with this horrific, bloody history that we laid down. In both the United States and in Europe, composers were fighting a battle over the soul of music, a war between Eros and Thanatos, between love and death, between music as a restorer of the spirit, on the one hand, and music as a witness to the darkest deeds that we’ve unleashed on the world over the last one hundred years. Alex Ross’s book The Rest Is Noise was a great source for me while I was working on my book. It’s very good at describing this splitting of music by the darkness of the twentieth century.

This split plays out in Peter’s life. He has a natural ability to write a delightful melody and to harmonize it in a pleasing, neo-romantic way. He inclines by nature toward a music of assertion. But his academic training and his conscience turn him toward a music that wants to explore the darker, guiltier, more troubled side of the human experience. That fight lies at the heart of his story.

You can trace the same battle in American music, even within individual figures like Copeland, who had this dual nature as a great populist writer of instantly attractive melodies on the one hand, and on the other, as an academic composer of more jagged, serial music that has largely been forgotten. Another composer mentioned in the book who wavers between the music of lightness and the music of darkness is Peter Lieberson, who stands in for that whole generation of composers led downward into an underworld of complexity and difficulty, yet who live long enough to come back out and repudiate that music. Lieberson even said he wanted to apologize to his own students for making them take a wrong turn!

But I’m not personally convinced that the turn toward darkness is intrinsically wrong. The turn toward difficulty and thorniness isn’t necessarily something we want to demonize and ban. Something in me is sympathetic to Adorno when he says that serial music “takes upon itself all the darkness and guilt of the world.” We need a music large enough to incorporate everything in our soul, even that tangled darkness. But I wanted to tell the story of a man who starts out at a neo-romantic moment, takes the turn that serious and academic composition takes, and then lives long enough to see everything that he’s committed to get washed away and replaced by another kind of neo-romanticism at the end of the day. And I wanted to tell that story in a way that would make a reader’s sympathies vacillate, so that at times the reader would feel that there’s something misguided and alienating about this project, that Els is guilty of that same wrong turn that so much of modern music is guilty of, trying to push the ear so far that it cuts off its audience and leaves them with something unhearable. But at other times, I want the story to twist and change so that the reader might feel in Els’s pursuit something stubbornly valuable and almost heroic. In a culture like ours today, where only the beautiful and the easily accessible and the affirmative get played again and again, we have a new need for music that might complicate and deepen the story.

KM: It’s difficult to tell whether Peter Els’s descent into this kind of dark underworld of twentieth-century music is heroic or self-serving. The motivations aren’t always clear, whether it’s an attempt to achieve immortality or whether it’s artistic compulsion or the search for beauty . . .

RP: Yes, in fact if you go through the book and list all of the moments where Peter Els’s inner narrator says something like “all he ever wanted to do was X,” you’ll find him often contradicting himself! That, of course, is me trying to find ways of dramatizing how the creative impulse is itself a battle between the simple and the complicated. It wants to continuously reassert itself with something elemental and childlike in its simplicity, but in fact it always multiplies, it’s always restless, it’s always moving toward its opposites and searching out byways that haven’t been sought out before.

Of course any creative motivation is complicated enough. But I think you’re right, when the motives are unclear, the emotional response to the effort becomes ambiguous. It’s never certain whether Peter’s desire to make something new, something that hasn’t quite existed yet, is completely laudable and wonderful, or whether it’s mingled with something more grandiose and self-serving, something almost Faustian. But that’s music, too. Its motives will never be completely pure, because it’s made by people, who do all kinds of things for all kinds of reasons, and in some ways the motive becomes almost immaterial, because people can do the right thing for the wrong reason and vice versa. Thorny composers can write something simple and ineffable despite themselves! And the same pieces of music we were talking about earlier—the work of Messiaen and Shostakovich and Harry Partch and Cage that are so difficult and inaccessible to some—can become lively invitations to an immense and ravishing dance, when something comes along to give a listener a key.

IV. WE HAVE TO LOSE OUR WAY

KM: Peter Els claims to encode music in the chromosome of a living cell, a piece that might never be heard by its audience. This raises some difficult artistic questions: what’s the significance of music that can’t be heard; does that fit the definition of music at all . . . He’s moving past strictures of tonality and rhythm, and bypassing sound altogether.

RP: Yes absolutely, but he’s also working paradoxically out of a long and rich tradition that is older than he is, coming through people like John Cage who want to question what making and listening to sound is all about. In a sense, this attempt to make a music that is everywhere at once but can’t be heard is the ultimate conceptual extension of the preoccupations that Cage wrote about, mostly in those gnomic assertions of his where he questions the boundaries between music and noise—the sorts of assertions that hover over Els and then become muses in their own right—things like Cage saying, “If something’s boring for two minutes, do it for four minutes; if it’s boring for four minutes, do it for eight minutes . . .” Those kinds of gestures, in their infancy, were incredibly refreshing and really challenged the easy relationships and the mindless consumption of beauty that infused the culture of concert music. They forced listeners to take seriously the miraculous ability of humans to listen to patterned sounds and to extract euphoria from them. And yet those same gestures, those same provocations that were so refreshing in their initial urgency did, in the run of time, become iconoclastic and then ultimately destructive, alienating, producing a deadening repetition in their own right.

This fight to stay fresh to possibility, to actively attend to what we’re hearing: it’s unwinnable really. We’re not built to stay focused, we’re not built to stay ecstatic, we have to lose our way, and musical creators will always look for gestures that reject what has come before in order to reawaken us, paradoxically, to possibilities that have been lost. But they will also look to continuity, to legacies, because if you throw away everything of significance in the name of the new and in the name of attention and transformation, then you’re left asking people to attend to something that isn’t human, that is too alien to give any kind of solace or understanding. We seem to live in this eternal contest between the familiar and the strange, the reassuring and the alienating.

KM: Els contemplates his lifelong familiarity with certain pieces throughout Orfeo. It seems that the test of good music for him is whether it has a kind of inexhaustibility . . .

RP: Yes. He’s wrestling with this inverted V curve, the one that we all wrestle with as listeners. When we first hear something new, we ascend this rising curve of pleasure, where the more familiar we become with the work, the richer and deeper our understanding of what’s going on inside of it becomes, and the more we love the new piece. But the problem with the mind’s desire to understand and embrace is that we ultimately kill the joy with overfamiliarity. We get to the top of that curve, and further exposure just starts to make the whole thing so familiar and predictable that we can’t hear it anymore, and we descend into attenuation. We’ve loved the thing to death. And you know, there isn’t a masterpiece in the world that can’t be rendered completely harmless by overfamiliarity. The Barber Adagio for Strings is actually an extraordinary piece. It’s very jarring in the way that its harmonies unfold. We’ll never be able to hear that again, those of us who have lived long enough to hear that thing be used for every possible soundtrack for grief.

What’s interesting about this battle between the familiar and the strange is that it connects us back to Cage, and also connects Cage back to Beethoven and Beethoven back to Bach and Bach back to Gesualdo—all these figures who are trying to put new wine in old bottles, or old wine in new bottles. There is this great thread in music-making that goes as far back as the earliest written music: an attempt to leverage expectation by making the listener sufficiently familiar and oriented enough to predict what will happen next, and then doing something else, something unstable or unpredictable or surprising. A good melody and an interesting harmonic progression are always games between how the line should behave and what it actually ends up doing. You can hear in Cage, despite all his Zen iconoclasm, a thread of post-romanticism, which is itself already obsessed with playing surprise off of expectations and with stretching transgression to the breaking point. Music is forever being broken and remade.

V. THE CHAOTIC IMPULSE

KM: There’s something Bach-like about the structure of Orfeo, the way that certain ideas are put forth and then dissolve only to reappear in different guises. Something Baroque, perhaps.

RP: Well the book is highly contrapuntal. It is, without giving too much away, a fugue. And you have to remember that the word “fugue” and the word “fugitive” come from the same root. Both of them are flying.

KM: You seem to have always had an affinity for Bach. What personally draws you to his music?

RP: You know, he has been my wellspring for my whole life. I put in the book this episode toward the end of Els’s life where, after coming this enormous distance and slogging through the decades trying to extend his musical vocabulary, he has this moment of recuperation near the end where he spends over a year listening to nothing but Bach. I actually did that in my own life back in my twenties. For me it was closer to eighteen months where I listened to nothing but Bach. Everything he wrote. That’s all that I wanted, every day, one day after the next.

Why? Well, you know Nietzsche talks about the Dionysian and the Apollonian in The Birth of Tragedy, about these two modes of art, one concerned with pattern and structure and the exploration of higher orders of order—the Apollonian—and the other—the Dionysian—devoted to passion and disruption and the inchoate swamping of order by chaos and voluptuous excess. It’s a simple dichotomy, and there is no composer for whom either one of those labels entirely fits. You can look at Scriabin and find the Apollonian, and you can look at Milton Babbitt and find the Dionysian. What I love about Bach—and again there is this wonderful essay by Adorno, “Bach Defended Against His Devotees”—I love him because I believe that his music somehow reaches across that false dichotomy and shows the passion inside structure and the voluptuousness and explosiveness inside patterned order.

As a writer, I’ve sometimes elicited readings that say my books are very idea-driven, very pattern-driven and somewhat lacking in passion. Those criticisms are sometimes made against Bach’s music as well, but I believe that the person who takes time to understand the vocabulary of Bach and to learn just how dynamic and inventive and restless and simultaneously patient his compositions are, just how broad his treatment of dissonance is, how shocking his music can be when you understand the expectations out of which they grow—that person will hear just how revolutionary and adventuresome Bach can be. I take heart in that because I feel that the Apollonian caricature of Bach’s music by people who are brought up on a kind of romanticism gives way, with repeated exposure, as you climb toward an understanding of just how deep those waters run and how deep that passion is. And I hope that readers can look at a book like Orfeo and see the intellectual nature of the book and the book’s structural complexities, and yet still feel the desperate and passionate, chaotic impulses driving these characters forward in a dark and confusing world.

VI. THE MEMBRANE BETWEEN THOUGHT AND FEELING

KM: You’re definitely known for having an interest in moving past false dichotomies. I think many people are drawn to your novels partly because of your dedication to moving past these clichéd demarcations between science and art and the notions that they’re entirely disparate intellectual disciplines that can’t inform one another. You seem to get at that often through finding the parallels between science and music, more specifically between genetics and chemistry and the kind of linguistics of music, how phrases and ideas evolve . . .

RP: Absolutely. You’ve articulated that beautifully. On the outside, that false dichotomy breaks down with every work by every composer worth anything, and people are constantly surprised by influences that connect seeming opposites. You know, for instance, Chopin was a great lover of Bach. That’s going to baffle the listener of Chopin who just wants the nocturnes to wash over him in all their chromatic, romantic turbulence. Bartók was a great lover of Debussy, and he said that his music was deeply influenced by Debussy’s music. I love those surprise genealogies that show how permeable the membrane between thought and feeling really is. I love those surprising ancestries, when you do the paternity test and realize how far individual makers have travelled across that spectrum between heart and head.

As far as this division between science and art, I mean you put your finger on it. It’s Nietzsche’s dichotomy writ large. People want to say science is somehow this rigid, prescribed, formalist, dehumanizing set of relations and rules, whereas art is this lovely, seductive, turbulent, unpredictable human force, and the reality is that those disciplines are a lot closer than people give them credit. There are strong patterns underneath even the most turbulent and organic and voluptuous art, and there is tremendous chaos and conflict and human drama in the practicing and interpreting of science. Both science and art consist of endless propagating experiments and speculations of what is and what might be. You know there’s a wonderful Lewis Thomas quote on that topic. Thomas was a doctor and a research scientist but also a writer and a deep lover of music, eclectically moved by composers from Bach to Mahler, who he cites constantly in his essays. In a wonderful essay called “On Matters of Doubt,” he writes:

I must try to show that there is in fact a solid middle ground to stand on, a shared common earth beneath the feet of all the humanists and all the scientists, a single underlying view of the world that drives all scholars, whatever their discipline — whether history or structuralist criticism or linguistics or quantum chromodynamics or astrophysics or molecular genetics. There is, I think, such a shared view of the world.

It is called bewilderment.

Keenan McCracken is an associate editor at Other Press.

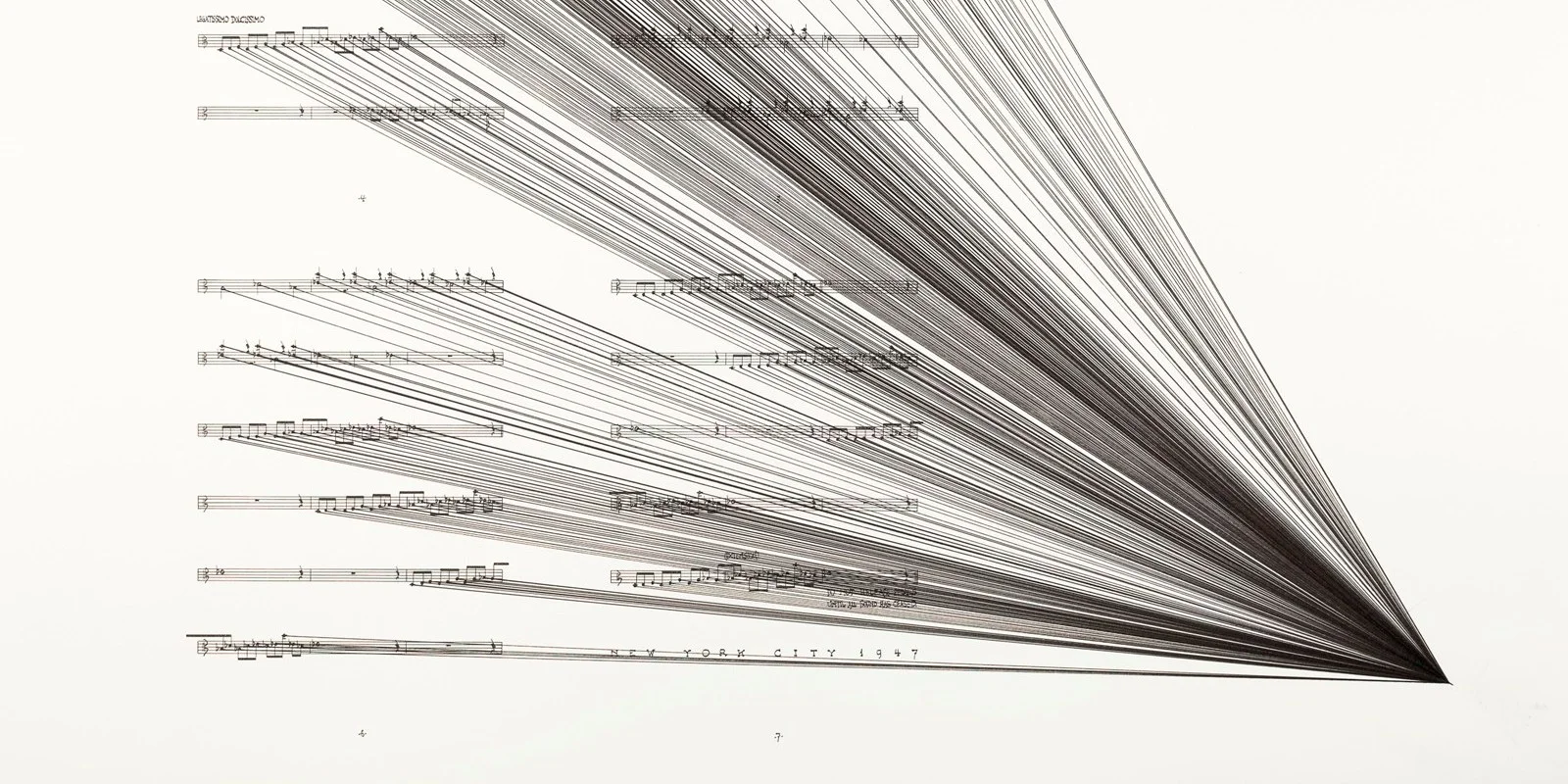

Banner image: Marco Fusinato, Mass Black Implosion (Music for Marcel Duchamp, John Cage) Variation I, 2012 (Part 2 of 2). Ink on archival facsimile of score. Two panels, each 81 x 107cm. Private collection; courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery.