This article appears as part of a 140-page portfolio of new and newly translated literature on the life's work to date of Kaija Saariaho. Click here for full details on Music & Literature no. 5.

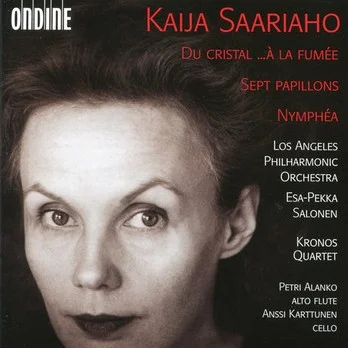

Saariaho: Du cristal / À la fumée / Sept Papillons / Nymphéa

by Petri Alanko (flute), Anssi Karttunen (cello), Kronos Quartet,

Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra

Esa-Pekka Salonen (Conductor)

(Ondine, 1995, reissued 2013)

Kronos first met Kaija in the summer of 1984 at the Darmstadt Festival of New Music. I remember it was the same summer that we played Morton Feldman’s big and beautiful String Quartet No. 2 there. And it was the same festival where we met Kevin Volans, the South African composer who would go on to write White Man Sleeps and Hunting:Gathering for Kronos—very important works in our repertoire, and among the first string quartets ever by an African-born composer. So in meeting both Kaija and Kevin, Kronos began two very important relationships that summer.

I heard a piece of Kaija’s performed at Darmstadt. Afterward, she and I corresponded, and she sent me an LP of her music. The thing that was amazing to me about her music, from the very first time I heard it, was the sheer variety of sounds, and the way acoustic instruments and electronics felt so natural together. It also seemed natural to me that Kaija should write for Kronos, and so I asked her, and eventually Nymphéa arrived.

Nymphéa was perhaps the first—or at least, among the very first—pieces Kronos ever played that involved live electronics. This was long before the days of laptops, of course, and to perform the piece required a very particular form of machinery—something developed while Kaija was at IRCAM, I believe. It was so complex and so specific to Kaija that both she and her husband, Jean-Baptiste Barrière, had to be there in order for Kronos to perform the piece. We didn’t have our own sound person at that time, so performing Nymphéa represented a big step in the evolution of our work, and of our team. It was also one of the first times in our history that a piece required that a sound engineer be able to read a score—there were specific cues that had to come in at exact moments during the live performance. It was a direction we’d continue to explore with Steve Reich’s Different Trains (1988) and many works since then. But it was really Nymphéa that prompted this growth of our work with technology in concert.

A page from a working draft of Kaija Saariaho's Nymphéa. Courtesy of Kaija Saariaho.

Initially, because of these technical requirements, we weren’t able to play the piece that much. But when we did, it took our sound world into totally new places. We were able to transform a concert hall into a very different space. At various points in Nymphéa, we develop the sound further by adding in our voices, reciting a poem by Arseniy Tarkovsky. We’d chanted and shouted before in George Crumb’s Black Angels—the voices are counting in various languages, sometimes like drill sergeants. In Nymphéa, the voices are very internal, very sensitive, just like Kaija herself. That’s something about Kaija in general: her music is so much like she is that for me, listening to her work is very much like talking with her, and vice versa. I think of her work and her personality as being almost the same. (Which is basically the polar opposite of Morton Feldman, who was outgoing, even brash in person, but whose work is often so quiet and reflective.)

In working with Kaija on Nymphéa, first in our rehearsals and then later in the recording, it was wonderful to experience how clear she was about the sound and feeling of the music. That was the most important aspect of the process to her: arriving at that particular sound and feeling. One thing I always sense about her is that she listens to the center of the music in a very beautiful way.

I was reading something once where Kaija was describing the nymphéa—the water lilies—how they grow out of mud and darkness, and out of that mud comes this unbelievably beautiful flower. Her comment made me think of all the lilies I’ve seen—and all the depictions of lilies in art throughout history. The nymphéa is the sacred lotus from ancient Egyptian art, and of course, closer to our own era, it’s the water lily of Monet’s famous series of paintings. The sound of Kaija’s music definitely brings to my mind the look of Monet’s coloring, from the panels of water lilies I’ve seen in Paris. When I step back and listen to Kaija’s piece, I can feel what she was describing in that article I read: it’s like the high frequencies of the violins blossom, but beneath it there’s this earthy, or muddy quality. It captures my imagination and my feelings just as powerfully today as it did back in 1987, when Kronos first received Kaija’s score. And Nymphéa has been a key part of Kronos’ sound for all these years.

David Harrington is a violinist and the founder of the San Francisco-based Kronos Quartet. He is also the Artistic Director of the non-profit Kronos Performing Arts Association (KPAA), whose mission is “to continually re-imagine the string quartet experience.” KPAA has commissioned more than 800 works for string quartet and manages Kronos concert tours, recordings, and education and community programs for all ages.

Banner image: Kronos Quartet in concert. Photo courtesy of Jamie Young.