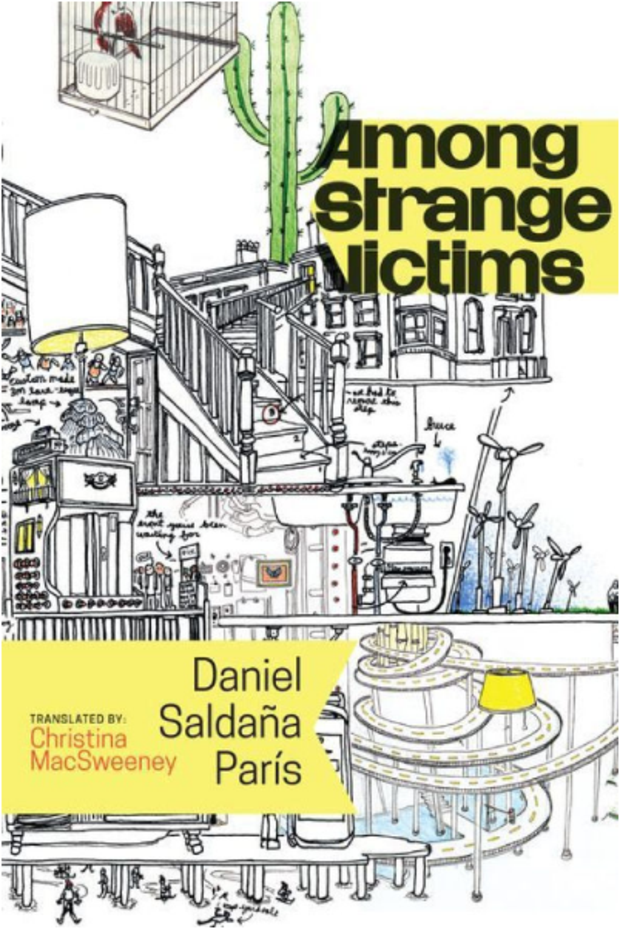

Befitting its role as an arts journal committed to publishing and promoting underrepresented artists from around the world, Music & Literature is pleased to inaugurate a monthly fiction series showcasing new and distinctive voices from around the globe. Our first piece features the disarming yet keenly pointed prose of Daniel Saldaña París, a Mexican author now living in Montréal who has been championed by such hispanophone compatriots as Valeria Luiselli, Mario Bellatin, and Yuri Herrera. His equally uncategorizable début novel, Among Strange Victims, will be published in Christina MacSweeney's translation this June.

Among Strange Victims

by Daniel Saldaña Paris

tr. Christina MacSweeney

(Coffee House, June 2016)

She, my mom, died on October 12, Columbus Day. A nice piece of irony on fate’s part as she was a historian and had dedicated the better part of her career to the study of the so-called discovery of America, something that occurred, so they say, on that date—as if it were possible to discover anything so large in one day. She, my mom, lived alone in a two-bedroom apartment in Coyoacán, with floor to ceiling bookshelves, on which I never found a single thing that interested me. I generally visited her on Saturdays, although sometimes stretches of two or even three months might go by when neither one of us did anything about seeing the other. Then she’d call me on a Friday evening to say someone at the university had given her a carrot cake and I could come over and try a slice the following day. Of course, it wasn’t true: she, my mom, used to buy those cakes herself to attract me when her guilt about that ebb in our relationship caught up with her. In other words, the carrot cakes were, as they say, a decoy.

Besides the visits to her, my mom, there weren’t many other people I saw regularly, by choice. I had a cordial, you could even say warm relationship with two colleagues at the office, but I’d broken off completely with my small circle of teenage friends, and had never bothered to replace those friendships. So when she, my mom, died, I suddenly found myself alone in the world, as they say, and despite what you might think, that was an enormous relief. All of a sudden, there seemed no point in keeping my job—I’d only taken it to please her, my mom—and I resigned with immediate effect to spend my time more usefully putting all her—my mom’s—papers in order.

I sold the apartment in Coyoacán through a real estate agency that charged a very high commission, but even so, between what I got for the apartment and what she, my mom, had somehow or other saved, I was left with four million pesos in my pocket. One of my old colleagues at the office, who I still saw, said he could help me invest the money responsibly, to give a small but steady income. I thanked him for his offer, but refused, and gave him all my plants before leaving my own apartment and moving, with a suitcase of clothes, to New York. I also tried to give him all her—my mom’s—books, but my former colleague said, as they say, politely, No.

I’d never been to New York before, but she, my mom, had once told me that I’d been conceived there; that’s to say, she, my mom, had been in New York at the moment she’d gotten pregnant through, I suppose, the traditional method of making love—she didn’t specify. And so I thought going to New York was a homage to her, my mom, and also a way of starting afresh, returning, as they say, to the point of departure.

After a week living in a hotel room, I finally found an apartment of my own: a shoebox, as they say, on a very distant point of the map, at the end of a subway line. The neighborhood was mostly inhabited by Dominicans and the building was owned by a likable Greek guy. The building was, as they say, falling apart.

First I slept on one of my padded jackets, then on an inflatable mattress the likable Greek lent me, then on a bare mattress I bought at a discount, then on a mattress, still bare, but with a wooden base I bought at a discount, and finally on an, as they say, proper bed, that’s to say with sheets and blankets. It was winter by then and, in addition to the bed, I’d bought a whole pile of Scandinavian-design furniture that made my apartment into something similar to my old office, in Mexico. That resemblance comforted me.

The likable Greek was very lonely because the—as they say—love of his life was dead, so he used to come by quite frequently to ask me what I was doing. One day, as I’d gotten tired of telling him I was doing practically nothing besides buying Scandinavian-design furniture, I began saying I was writing a novel. The Greek, who used to wave his hands about a lot, was very relieved.

In the Dominican store where I shopped for food, there was a girl, by the name of Disney, who—as they say— used make a hullabaloo whenever I came in. El mexicano, Disney would say, El mexicano. Disney also used to ask me, every time I came in, what I’d been doing, and as I’d gotten tired of telling her I was doing practically nothing besides buying Scandinavian-design furniture, one fine day I began saying I was writing a novel. And Disney was very happy about that, and began, as they say, making a hullabaloo about my novel whenever I came into her store: El novelista, Disney would say, El novelista.

Below my apartment, on the first floor, was a larger, empty apartment. The likable Greek posted flyers all over the Dominican neighborhood to see if he could manage to rent it out, but no one ever called. One fine day, the Greek said that if it wouldn’t, as they say, take up too much of my time, I could advertise the apartment myself, with my own flyers, show it to anyone who might be interested and if I found a tenant, he’d discount a hundred dollars from my rent. I didn’t, as they say, need to do it, as I had her—my mother’s—money, but I was tired of doing practically nothing besides not writing a novel and I said sure, that was fine. The Greek was very relieved and waved his hands about a lot.

I didn’t prepare any flyers to post around the Dominican neighborhood because it was cold and I wasn’t interested in going out, except to Disney’s store—she always made a hullabaloo—but I did put an advertisement on the internet, on a web page for renting out apartments. On the second day, someone replied to my advertisement, asking to view the apartment. It was a woman—or a man—who signed herself, or himself, Vanessa. I said I’d meet her or him at Disney’s store because I thought she, Disney, would be, as they say, very excited to see me with a stranger, and she'd make a hullabaloo about it.

I’d already been waiting a good while when the woman who signed herself Vanessa—she was a woman—turned up. And she didn’t turn up alone: she came with her daughter, who was also called Vanessa, she said, but whose name, she told me, was spelled differently, with a single s: Vanesa. Vanessa, with a double s, was a woman in her early forties, very—as they say—well preserved, who smiled a little as she spoke, and Vanesa, with a single s, was a very, as they say, cute, teenager who never smiled at all. When she saw me with them, Disney made a hullabaloo: El novelista y las gringas, said Disney, El novelista y las gringas.

While we were walking back to the Greek’s building, Vanessa told me, in English, that her husband had died, and I told her, in English, that she, my mother, had died, so we exchanged condolences. Vanesa didn’t say anything but I noticed she was scowling at her mother, Vanessa.

They thought the apartment was acceptable, as they say, and the next day they came back to sign the rental agreement with the likable Greek. The Greek was very relieved I’d managed to rent out the apartment so quickly, he said he’d discount a hundred dollars from my rent and waved his hands about a lot. I went to Disney’s store to buy beer (El novelista y la cerveza, said Disney, El novelista y la cerveza) and Vanessa, the Greek and I toasted the occasion in the empty apartment. Venesa wanted to join in the toast too but Vanessa said no way and she, Vanesa, scowled at her, at her mom. A few days later they moved in.

Vanessa had heard from Disney that I was a novelist—I wasn’t a novelist—and told me that one day she’d like to read a bit of what I was writing. Her deceased, as they say, husband had been a professor of literature. I said sure, that she should come up one day and we’d have a beer—around that time I’d begun drinking beer almost every day. Vanesa started high school nearby and I only saw her occasionally, in the afternoons, walking toward the likable Greek’s building, scowling about something.

One day, while Vanesa was at high school, Vanessa knocked at my door and came into the apartment, at my invitation, to have, as they say, a beer with me. And we had a beer. Then we made love, as they say, traditionally.

Another day Vanessa knocked on my door and, fortunately, didn’t say anything about reading my novel, just opened a beer, and we drank it, and then we made—as they say—love, very traditionally. And the same thing happened another day. And then we were, as they say, sweethearts. Sometimes we’d go out together to buy beer at Disney’s store, and Disney would make a hullabaloo: Los sweethearts, Disney would say, Los sweethearts. By that time, I hardly ever thought about her, about my mom, except when I thought about what I’d do when I’d run through the money—hers, my mother’s.

One day, Vanessa told Vanesa we were sweethearts and Vanesa scowled at her, at her mom.

After that there were a lot of days when nothing, as they say, happened.

Winter came to an end and—surprise, surprise—spring began, and Disney was happier than ever, and made more of a hullabaloo; La primavera, Disney would say, La primavera. The Greek was more relieved than ever, and waved his hands about even more. Vanessa was happy as well because now she almost never thought about him, her deceased husband, the professor of literature, and knocked at my door every day to make love, as they say, traditionally. But Vanesa wasn’t happy, she was furious. She was always scowling at Vanessa, at Disney, at the Greek and at me.

One day, I’d been drinking a lot of beer and considering the idea of writing a novel when the police knocked at my door. They made a hullabaloo: Police, they said, Police. I opened the door, drinking a beer, and they got me in an arm-lock. One police officer came inside, and then another police officer, and then another police officer, and then Vanessa, who was crying. That him, ma’am? one of the police officers asked Vanessa in English, and then another police officer asked Vanessa, also in English: Is it him? And Vanessa said Yes, it’s him, and they took me, as they say, into custody. In the street, outside her store, Disney was making a hullabaloo: Se lo llevan preso, said Disney, Se lo llevan preso.

One police officer and then another police officer and then a lawyer explained to me in the police station that Vanesa had told her, told her mom, that I’d made, as they say, love to her, to Vanesa—traditionally. That I’d been drinking beer and had made love to her, as they say, traditionally. There was a hullabaloo.

In court, the Greek—who was waving his hands about a lot—stated that after I’d met Vanessa and Vanesa, I’d said Venesa was, as they say, very cute. There was a hullabaloo.

In court, Disney stated that I used to buy a lot of beer. Disney cried. There was a hullabaloo.

In court, Vanesa, scowling, gave evidence, and so did Vanessa, who spoke about her deceased husband, the professor of literature. Vanessa also spoke about how we had made love, as they say, traditionally. I gave evidence too, in court, but I got all mixed up explaining that I was and wasn’t writing a novel, and that I had made love to Vanessa—with a double s—but not to Vanesa—with a single s. There was a hullabaloo.

In the end they declared me guilty and there was a hullabaloo. The judge gave a very pretty speech about the illness of making, as they say, love to children, and sent me, as they say, to prison. It was October 12, Columbus Day: a nice piece of irony on fate’s part.

Translated from the Spanish by Christina MacSweeney

Daniel Saldaña París is a poet and novelist. He has published two collections of poetry: Esa pura materia (That Pure Matter) and La máquina autobiográfica (The Autobiographical Machine). In 2013, he published his first novel, Among Strange Víctims to critical acclaim in Mexico. In 2015, he was included in México20: New Voices, Old Traditions, published in the UK by Pushkin Press.

Christina MacSweeney is a literary translator specializing in Latin American fiction. Her translations of Valeria Luiselli’s Faces in the Crowd, Sidewalks, and The Story of My Teeth were published by Granta and Coffee House Press in 2012, 2013, and 2015, respectively Her work has also appeared on a variety of platforms, including Granta online, Words Without Borders, McSweeney’s and Litro magazine.