At sixty plus, Mircea Cărtărescu (Bucharest, 1956) still retains an intriguingly youthful air. This is down, in part, to his looks—the piercing gaze and wry smile, the long hair and almost adolescent slimness—, but also to his enduring sense of wonder at what he calls “the vast poem in which we live,” and, above all, to his boundless passion for literature. His own writing—unclassifiable, visionary, devastating—has been recognized by some of the most prestigious prizes in Europe and has a growing number of devotees around the world.

You could say that his work is a kind of love letter to Bucharest, to its mythologies and legends, to the history of the city and those who inhabit it. Cărtărescu constantly reinvents them, in the process reinventing himself in books that seek to unpack the infinite layers of what we call reality. As with Borges’ Aleph, everything can be anywhere at once (in a transvestite friend’s lip liner, in an old teenage flame), and any given moment contains within it the latent possibility of thousands more. Inside this melting pot, the improbable melds with the possible, the autobiographical with the fantastical, dream with nightmare.

I had the good fortune to meet Cărtărescu at the 2017 Winternachten Festival in The Hague, where we shared a long exchange over three days. Among other things, we spoke about Nicolae Ceaușescu’s architectural delusions of grandeur, the gradual transformation of Bucharest, the house in the woods where Cărtărescu has lived with his family for a decade, his love for Latin American literature, and his peculiar writing routine. Shortly afterward, he kindly agreed to answer the following questions by email.

—Rodrigo Hasbún

Translated from the Spanish by Sophie Hughes

Rodrigo Hasbún: You’ve told me that you write only one or two pages per day, always by hand, and you never revise what you’ve written. In other words, your first drafts are your final drafts, even in your longer work. What does this way of writing offer you as a writer? And has this always been your practice, or is it a method you’ve developed over time?

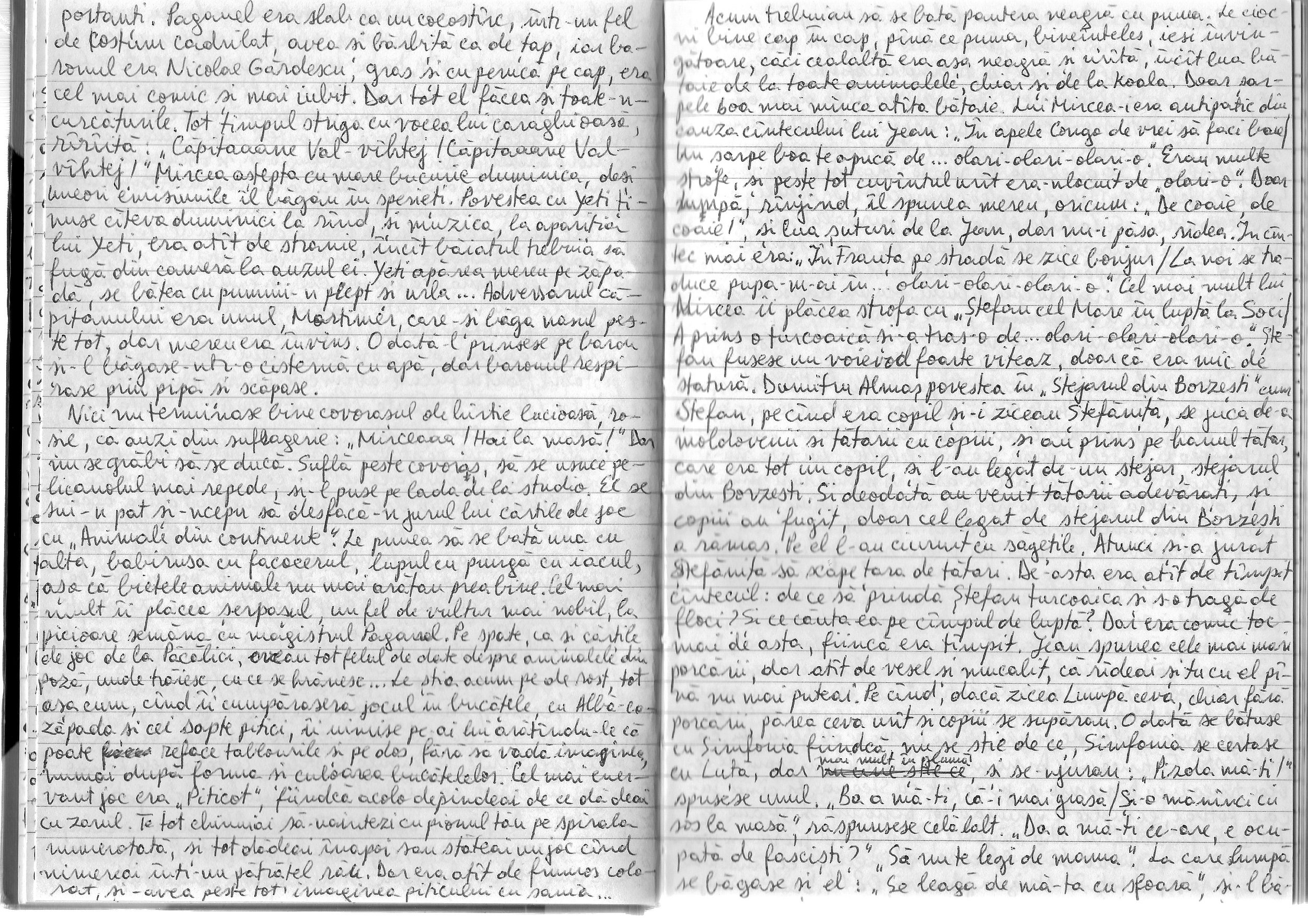

Mircea Cărtărescu: When we had those very pleasant talks in The Hague together, I told you that I always feel embarrassed when having to discuss my crazy method of writing, because I know that nobody believes me. Even I have a hard time believing that I wrote a 1,500-page novel, over fourteen years, by hand, and that the manuscript, gathered in four big notebooks, is as clean as if I copied it, page by page. Better stated: it’s as if the text has always been there, but covered over by white paint, and my only work is to erase that paint, revealing the manuscript beneath. Fortunately, I have my notebooks as proof.

A manuscript page from the notebooks of Mircea Cărtărescu. Courtesy of the author.

I write just one or two pages a day, yes, only in the morning, and I never add or take out anything. But what is important is that I never have a plan or a story in mind. Each page is revealed to me at the moment I start to write. Each page could (and does) change everything. This is the only way that I can write, for writing is not a job for me, nor an art, but a faith, a sort of a personal religion. To continue writing I don’t need to know where I’m headed, only that I can do it, that I’m the only one who can.

This is how I wrote my most important books—Orbitor v. 1-3 (Blinding v. 1), Levantul, Nostalgia (Nostalgia), and Solenoid—and this is how, for forty-five years, I have written my journal, which is the point of origin for all my writings.

Although in a strict sense you don’t write poetry anymore, you’ve mentioned that you consider yourself a poet above all else. Could you expand on this? What would you say poetry is for you?

Poetry is not an art of words for me but a special way of thinking and seeing things; it’s an oblique, child-like outlook on the world, at once the most natural and most unexpected experience of observation. A ladybug, a bridge, or a mathematical equation can surprise us with its grace: it’s poetry. A phrase from Plato or a principle of biology (“ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny”), a smile or a koan from Zen Buddhism—all are poetry. Poetry that is made of words is no different; it’s also a part of the huge poem in which we live.

I started as a poet, and wrote tons of poems during my youth. Even today in my country I am considered mainly a poet. But there was one day, when I was around thirty, that I decided I would never write another verse in my life. Another thirty years followed and I’ve kept my word. Of course, I’ve written short stories that are actually poems, novels that are poems, essays that are poems, even my articles have something fishy in them that I call poetry. It makes no difference to me if I write prose, verse, or if I do not write anything at all. I am a poet, I have always been one.

A strong autobiographical impulse seems to drive much of your writing. Of course, raw materials quickly become literature as the past and the present, dreams and reality, the inner world and the world itself, blend together into a powerful mix. Nonetheless, in the heart of your books, I feel the autobiographical impulse still stands strong. Would you agree with this? Do you think of literature as a path of self-knowledge or self-exploration? As a Proustian way of recovering time, and of keeping the dead alive?

I’ve always written about myself to understand my situation and to heal myself (to paraphrase Kafka and Salinger, respectively). I was fourteen when the idea of solipsism first crossed my mind: I had no proof (for there is none) that anybody else really existed except me. Everyone else could have been characters in a dream. I’m not at all an egoist, but I am egocentric, even an egomaniac (as John Lennon said about himself). I have only one mine to explore, and to extract diamonds and mud from: myself. Sometimes I spend long days in introspection, charting inner Karstic landscapes, creating long inventories of extremely old memories, sensations, hallucinations, dreams, complexes, traumas. I’ve always been drawn back there to retrieve memories from the age of one or two, even from the womb, from previous lives, maybe. Yes, it is autobiography, but a fictional one, for I feel I have never really lived my life, but have constructed it, changed it in all kinds of anamorphic ways, invented and re-invented it; I have transformed it into an impersonal life capable of containing everything. My country has the diameter of my skull, but I hope the world reflects in it as in a drop of dew.

All this makes me think of Roberto Bolaño, a writer with whom you share some interests as well as a certain romanticism and an absolute passion for literature. Your writing method reminds me in turn of César Aira, who takes a somewhat similar approach. Have you read them at all, and are they writers you are particularly interested in? More generally, are you still as interested in Latin American literature as you were in the past?

I have not yet read César Aira, shamefully, and I’ve only read Bolaño’s The Savage Detectives, which left me with mixed feelings. But I know very well the work of other great Latin American writers. Borges is fundamental, no matter if you love him or hate him; Cortázar is the link between the European tradition of fantastic literature (German romanticism and surrealism) and South American magical realism; Fuentes left me breathless with his utter masterpiece, Terra Nostra; and Sábato, well, he’s my hero. It’s a bit of a hard thing to claim, but I think Sábato was Dante Alighieri for our age: a man of unfathomable depth of thought and imagination. I really love Márquez, of course, and Bioy Casares, Silvina Ocampo, Manuel Scorza… As you know, Romania, my country, is sometimes called “a Latin American country who got lost in Europe.” The similarities are striking: the same Latin blood and language, the same discrepancies between rich and poor, the same corruption, the same bandits in power. It’s no wonder that our literatures are also dominated by fantastic and imaginative trends, full of exuberance and profundity.

Despite your love for Latin American literature you’ve never visited any Latin American countries. Are there any particular reasons why this hasn’t happened yet? [1]

Well, over the last few years I have been invited to Argentina, Venezuela, Columbia, and Mexico, but I’ve never been able to convince myself to go through with such a long trip. There’s an archaic psychological hang-up, as well: for us Europeans, the other hemisphere is a bit taboo. In the Divine Comedy, Ulysses confesses that in his last journey he traveled south, saw new constellations, and came close to the Mount of Purgatory, but he died there when God sent the storm that swallowed his ship. This was punishment for his audacity. Besides, I have problems traveling by plane. The last time I went to the United States, one of my eardrums just popped when the plane descended into the Minneapolis airport... But I know that I will eventually get over my inhibitions and visit the wonderful countries of your continent, maybe when my latest novel, Solenoide, comes out in Spanish.

Unfortunately, your diaries haven’t been translated into Spanish, although it’s a genre that is increasingly read and well-respected in the Spanish-speaking world. What does diary writing represent for you?

My journal is made of the same stuff as my literature. It’s literature in the same way that my literature is actually a journal. Kafka used to write both his daily notes and his stories in the same notebooks, making very little or no distinction between them. It is almost the same with me. I cannot tell you how important it is to write these notes for me, day by day, drawing in my notebooks all the tropisms of my mind and body, each thought, each sensation, each symptom, each vision, each and every dream. It is my scriptural skin, following, in a topological way, all the protrusions and intrusions of my body, mind, soul. If I cannot write for three or four days in my journal, I suffer a real and painful panic attack.

I have published three big volumes of diaries in my language so far. Each covers a period of exactly seven years, so twenty-one years of my life are now properly mapped. I have recently published two additional volumes of seven years each. Only one volume has been translated so far, into Swedish. In Romania, my journals have always been quite controversial, sometimes scandalous, because of my unorthodox way of dealing with life and literature. Nevertheless, I believe in and will continue publishing them; they show my real face, as do my poems and novels.

You mentioned Kafka’s diaries as a favorite. What interests you most about them?

As the kids on the Facebook write: Kafka rulz! He was the greatest writer precisely because he was not a writer at all. He was more of a priest worshipping the demons of literature—as were Sábato and most others I greatly admire. Kafka’s journals, maybe more than his short stories and novels, reveal a formidable, speculative mind, a force that drives toward the very limits of language, which, as his homologue in philosophy, Wittgenstein, once stated, are the very limits of his world. I insist that he was not a writer, but an oracle. Borges had this same intuition when, in one of his stories, he named an oracle Qaphqua…

In “…escu,” a text that made me think of “El escritor argentino y la tradición” (the wonderful essay by Borges in which he questions a nationalist approach to literature), you write that it’s “not easy to be a Romanian writer.” It’s been twenty years since you wrote this. Over this time do you feel anything has changed in relation to what is expected from Romanian literature, or from your own literature and how it’s read, both in your country and internationally?

Rodrigo, you are a lucky writer, you write in a big international language. You are the inheritor of a huge culture that has Cervantes as an emblem. As for myself, I come from the middle of nowhere. My greatest problem when I publish abroad is simply getting people to read my books. Why should they do it? Who buys the books of an author from a country they’ve barely heard of, of which they know nothing? Who will take an interest in a culture when they’re unaware of a single writer who has emerged from it? My country is not only obscure, but also many times looked down upon for its poverty and its perceived low level of culture. What does a Romanian writer look like? Nobody knows and I’m afraid nobody cares.

No, my situation changed very little over those twenty years. I still consider myself an unknown and little-published writer abroad. But of course I can very well live with that. My only dream is to write another page that I like. Nothing more, nothing less. I’m afraid this is a bit harder to achieve than is becoming a well-known writer.

On a final note, what would you say is the role of fiction in troubled times? Do you think fiction writers as fiction writers bear any particular responsibilities?

Sometimes I am quite optimistic, but that isn’t the case now. I consider myself fortunate that I got to live and write in better times. Now I have a dark and bitter perspective on the world, literature, and myself. I think we are all heading toward Armageddon—many signs point in this same direction. I doubt that literature means too much to people anymore. Literature is for cultured, sophisticated people who think with their own minds. These people are a minority who don’t factor into politics, into the cultural sphere, or into any defined sphere, really, anymore. On the contrary, they suffer, like all minorities, from the tyranny of the majority. Though it’s the most wonderful of all arts, the art of the word—poetry, fiction—seems obsolete as compared to the art of the image or those of sound. Ten years ago you would see people reading books on beaches or on the bus. This habit seems to have died.

Under these conditions, it’s no wonder that the writer’s status is in free fall. Who cares about good fiction anymore, when people have endless TV, enough to stream over them like a tropical rain? Of course, armies of novelists write on fashionable topics or try semi-fiction or non-fiction to draw an audience, but it doesn’t mean that even they are listened to. As for myself, I don’t give a damn about drawing attention; I will go on simply trying to write good literature, for this is the only obligation of a writer, his or her only responsibility. If you write well, you are saved; if not, you may be the greatest activist of all time but your efforts will be in vain. Even if nobody on Earth is able to read, I will go on writing. I will continue writing even if I am the last man on Earth.

Mircea Cărtărescu is a writer, professor, and journalist who has published more than twenty-five books. His work has received the Formentor Prize (2018), the Thomas Mann Prize (2018), the Austrian State Prize for Literature (2015), and the Vilenica Prize (2011), among many others. His work has been translated in twenty-three languages.

Rodrigo Hasbún is a Bolivian novelist living and working in Houston. Affections, his most recent novel, has been published in twelve languages and is now available on paperback from Simon & Schuster.

[1] Cărtărescu has traveled to Latin America since the time this interview took place.

Ed. note: A Spanish version of this interview can be found here.