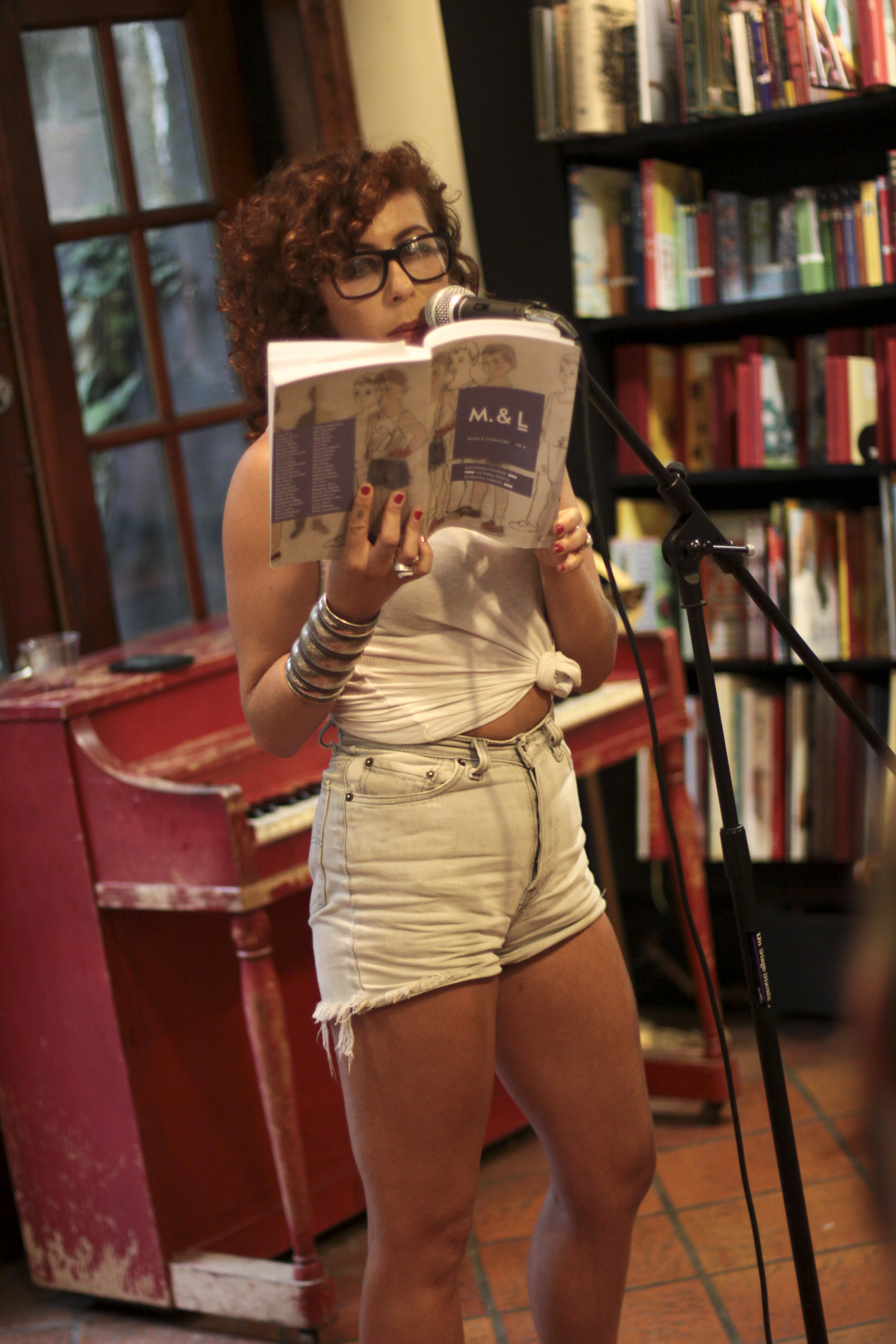

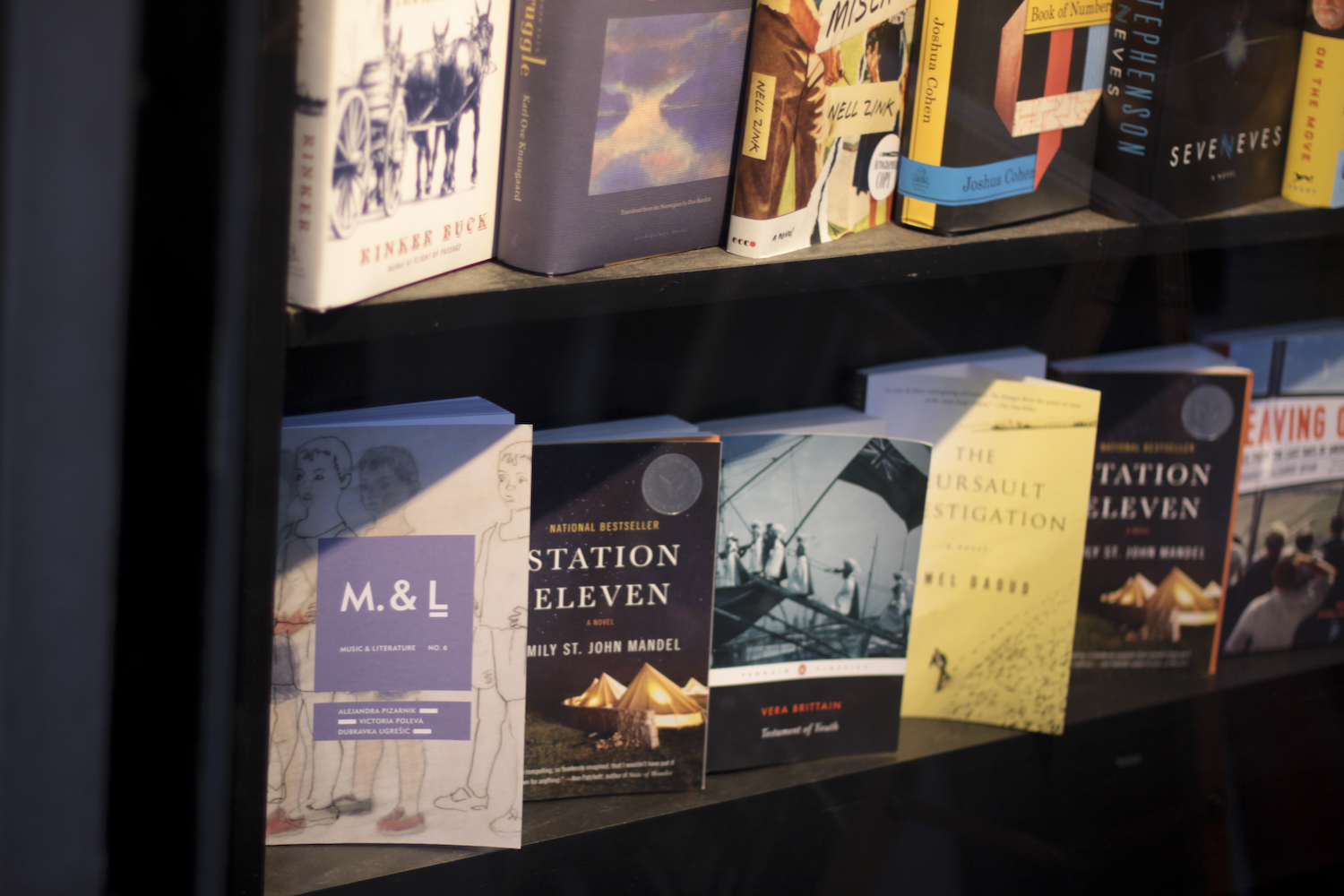

the brooklyn LAUNCH OF MUSIC & LITERATURE NO. 6: community bookstore / 30 june 2015

On June 30th, in the early evening, as the sun was sinking behind the Brooklyn brownstones outside, a crowd of readers and listeners gathered at Community Bookstore in Park Slope to celebrate the U.S. launch of Music & Literature no. 6, featuring Argentine poet Alejandra Pizarnik, Ukrainian composer Victoria Polevá, and the unclassifiable, post-Yugoslavia writer Dubravka Ugrešić.

Luthien Brackett (right) and Hannah Collins (left) conclude a pre-event rehearsal.

Before the event officially began, the audience listened as the musicians finished an impromptu rehearsal, filling in the event space toward the back of the bookstore, a long narrow bookshelf-lined room, with the doors on the back wall, behind the microphone, opened to reveal a garden with ivy colorfully splashed on the walls, which let the faint echoes of a quiet Brooklyn street into the space. A few minutes after 7pm, the bookstore event manager, Hal Hlavinka, approached the microphone, welcomed everyone to the store, to the launch of the new issue of the magazine, and introduced Music & Literature’s publisher and co-editor Taylor Davis-Van Atta to the stage.

Taylor mentioned the evening’s speakers and musicians—Ariana Reines, Emily Cooke, Matt Mendez, Hannah Collins, Luthien Brackett, Philip Huff, and Sara Nović—and concluded his introduction by reading a short prose piece by Stig Sæterbakken, “Why I Always Listen to Such Sad Music,” setting the tone for the event—the many false starts and internal struggles of artistic creation, silence, and finding the perfect means of expression:

Within each piece of music there is another piece of music, and that is the piece of music that we truly want to hear, and that is the piece of music we will never get to hear, and that is the piece of music that binds us to the music we hear, because it brings us into an unbearable almost contact with what we yearn for, that which we, as we listen to the music which almost is, but which nevertheless is not, can’t bear the thought of being without.

Emily Cooke reads from Pizarnik's letters.

The poet Ariana Reines then read entries from Alejandra Pizarnik’s journals (translated by Cecilia Rossi)—noting, first, their almost unbearable melancholy (whoever comes into contact with Pizarnik’s work seems to acknowledge this encounter with a mood of despair and awe)—from the summer of 1962, when Pizarnik was living in Paris: “Only once was I happy, when I ran after a horse, naked, along the beach. It was then that words such as earth, blood, sex, attained reality, became so real that my voice disappeared; and feeling and speaking couldn’t be told apart.” Following Reines, Emily Cooke read two of the letters between Pizarnik and her psychotherapist, León Ostrov, which Cooke translated for the number, while remarking at the uncanny thrill of being in a room full of people who knew Pizarnik, or at least knew her name.

Philip Huff reads from Dubravka Ugrešić's "A Story about How Stories Come to Be Written."

Next, Matt Mendez, Music & Literature’s Digital Music Editor, gave some context for understanding the work of Ukrainian composer Victoria Polevá, especially noting the total departure from her earlier compositions—highly stylistic, avant-garde, and characteristic of the perestroika era composers—into a style which, after converting to orthodox Christianity, could be reductively (and incorrectly, as Polevá insists) described as “holy minimalism.” Reading her brief biographical statement, translated by Ian Dreiblatt, along with sections from a conversation between Polevá and Anna Lunina, translated by Rachel Caplan, Mendez showed the many sides of a complex, subtle, and mysterious composer. After the introduction, the doors along the back wall were closed, cutting off the hushed noises from the street, while cellist Hannah Collins and mezzo-soprano Luthien Brackett took their places in front of the closed doors. The room was silent. (I could only hear the scratching of my pen on the page as I took notes.) Hannah Collins began playing, first the soft melodies, and then Luthien Brackett joined, filling the room with transcendent music, transforming Community Books into a temple, almost a place of worship, with notes fluttering across the worn-out rugs, and then, for a moment, there were only the faint, barely audible accents from the cello, as the resident cat brushed against legs and the legs of the chairs. The audience held on breathlessly, to the humid and holy music, and then applauded.

Dubravka Ugrešić was the subject of the final act. Philip Huff read from Ugrešić’s “A Story about How Stories Come to Be Written,” translated from the Croatian by David Williams, which narrated the author’s first trip to Moscow in 1975, mused on Boris Pilnyak, and made a lively portrait of Moscow’s Soviet-era library. Then Sara Nović read a lovely personal essay about Ugrešić’s work, exile, and language. The last burst of applause frightened the cat, who retreated to the front of the bookstore.

—Tynan Kogane

All photographs courtesy of Jesse Ruddock