THE new york city LAUNCHES OF MUSIC & LITERATURE NO. 6:

teatro, the italian academy at columbia universIty / 13 october 2015

book culture / 14 october 2015

|

13 October 2015 presenters

Jacob Ashworth, violin; Hannah Collins, cello; Patrick Duff, contrabass; Solon Gordon, piano; Kristin Gornstein, mezzo-soprano; Wayne Lee, violin; Hannah Shaw, viola; Taylor Davis-Van Atta, Deborah Eisenberg, Valeria Luiselli, Alan Timberlake, and Dubravka Ugrešić. |

Among classical music’s mysterious qualities is its ability to inscribe time’s passage with beauty and warmth, and thereby imbue such a passage with intimacy; even today, few composers achieve this effect more powerfully than Victoria Polevá. On Tuesday evening at Columbia University, the Italian Academy’s Teatro was filled for the release of Music & Literature no. 6 with a program that included live performances of two Polevá compositions, alongside presentations of work by Yugoslavia-born author Dubravka Ugrešić and Argentine poet Alejandra Pizarnik. The culminating performance of Polevá’s “No Man Is an Island,” a haunting piece based on the text by John Donne, left the capacity audience stunned, and proved a fitting capstone to a remarkable evening. And the elegant, ornate Teatro turned out to be an ideal setting, an intimate space of refuge where, as M&L editor Taylor Davis-Van Atta noted in his introductory remarks, “we can choose art over politics and sport, at least for one night.”

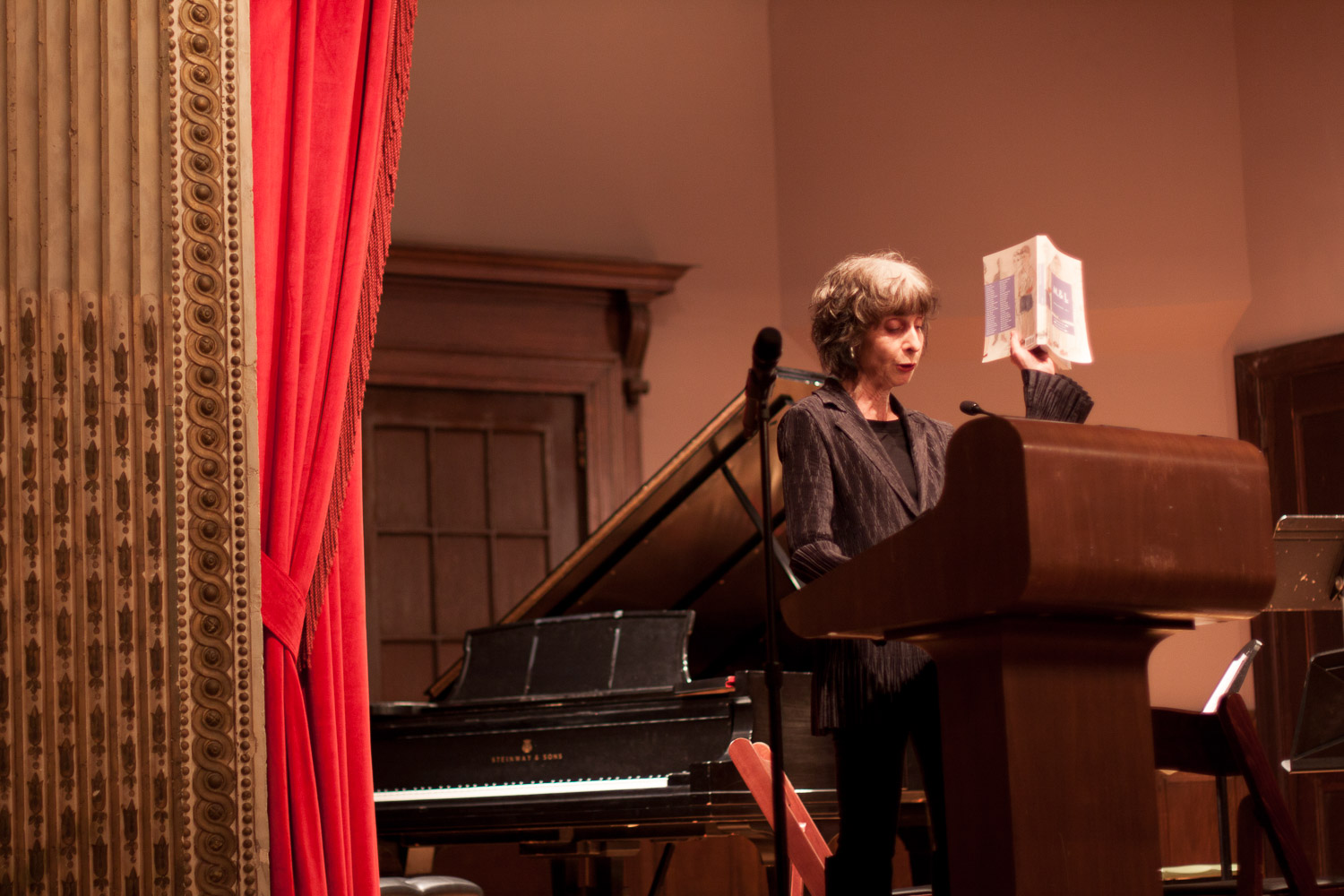

Deborah Eisenberg shares her appreciation of Dubravka Ugrešić.

Remaining true to the spirit of these words, Deborah Eisenberg opened the program with the tale of her first encounter with Ugrešić in Berlin “several surreal decades ago,” and a conversation about Isaac Babel (whom Eisenberg called “the secret handshake of writers”) that resulted in Ugrešić gifting her with a chocolate passport—a memento which, twenty-five years later, still resides in her freezer. Eisenberg then read from Ugrešić’s short fiction, “A Story about How Stories Come to Be Written,” an exploration of the nature of writing and memory that appears in M&L no. 6 for the first time in any language.

Ugrešić’s fictional realm is perhaps best characterized by the image—found in “A Story about How Stories Come to Be Written”—of a world in which “volcanic dust of oblivion constantly falls upon us, slowly burying us, like insoluble snow.” And in her deeply resonant voice, Eisenberg brought to life inquiries around the matter of myth-making, while displaying the humor of Ugrešić’s writing, as well as the serious questions her work so caustically confronts—namely, the question of upholding memory in the face of inevitable oblivion.

Dubravka Ugrešić herself followed Eisenberg and read briefly read from her novel, Baba Yaga Laid an Egg—an excerpt both lighthearted and fleeting—before engaging in an impromptu Q&A session with the audience, which immediately brought a more intimate feel to the room. Discussing the evolution of her own literary apprenticeship and artistic work ethic, Ugrešić emphasized the importance of a communal literary culture, a global community that transcends all borders and languages—even if this community, at times, exists entirely in the artist’s mind.

Dubravka Ugrešić engages the audience in an impromptu Q&A session.

After Taylor provided a few notes of introduction to the music of Victoria Polevá—including his first emails with the composer, from late 2013, when the maestro had quit composing to protest in the streets of Kiev—cellist Hannah Collins and mezzo-soprano Kristin Gornstein took the stage to perform Polevá’s “St. Silouan’s Psalm.” The performance emphasized the communal feel, as if everybody in the enraptured audience—students, faculty, long-term classical afficionados (I spotted Paul Griffiths seated along the center aisle)—were rendered equal by the tenderness of the “sound of the world,” to use Polevá’s own words. “Only through music and in music,” Polevá tells us in her interview in M&L no. 6, “can I restore the fabric that has been torn within me—there is no other way I can repair it.” This act of reparation and renewal manifested in the performance; one felt a powerful sense of solidarity, despite the volcanic dust of oblivion.

Valeria Luiselli reads from Alejandra Pizarnik's journals.

The performance of the psalm left the room silent for several seconds before applause broke the trance. And the reading of Pizarnik’s work that followed brought with it another palpable shift in mood. Valeria Luiselli’s humble presentation began with a note that she was on stage merely to “lend my voice,” to convey, however fleetingly, Pizarnik’s fragmented, tragic sentiments. The diary excerpts she read were both fragile and stirring, and portrayed a peculiar sense of isolation, of a “fear with no ending,” an evaporating life “without anybody.” In fact, I was reminded of a passage from Ugrešić’s fiction, in which she writes that “everywhere we leave constant traces of our existence, of our struggle against vacuity”; so too are indelible traces left in the mind by an event like this one.

The performance of “No Man Is an Island,” the utterly beautiful piece for chamber ensemble, seemed to encompass and enhance everything that had come before it, the beauty and the isolation, both of which are capable of producing awe. Indeed, the Teatro remained abuzz for half an hour after the final notes played and the concluding remarks were made. The evening’s presenters mingled with the crowd, with Ugrešić exclaiming “Polevá is a discovery!” while the musicians spoke with new admirers, the writers with aspiring student-artists eager to begin their own literary apprenticeships. It was like witnessing a new community being born.

The musicians take the stage prior to their performance of Victoria Polevá's "No Man Is an Island."

The coda to Tuesday’s event was an intimate gathering at Book Culture the following night, devoted exclusively to Ugrešić. The Paris Review’s managing editor Nicole Rudick began the night with a reading from Ugrešić’s The Ministry of Pain, followed by Philip Huff’s reading of his essay on Karaoke Culture from the latest M&L issue. Ugrešić and Sam Sacks finished the night with a lighthearted yet serious-minded conversation about the state of the publishing world and the future of literary communities in the modern world. Book Culture, one of the few bookstores left in the city whose focus is still primarily academic and literary, was the perfect setting for such an intimate discussion.

—Izaak Hecht

—Photographs courtesy of Jesse Ruddock

Special thanks to The Harriman Institute, cosponsor of the event at The Italian Academy