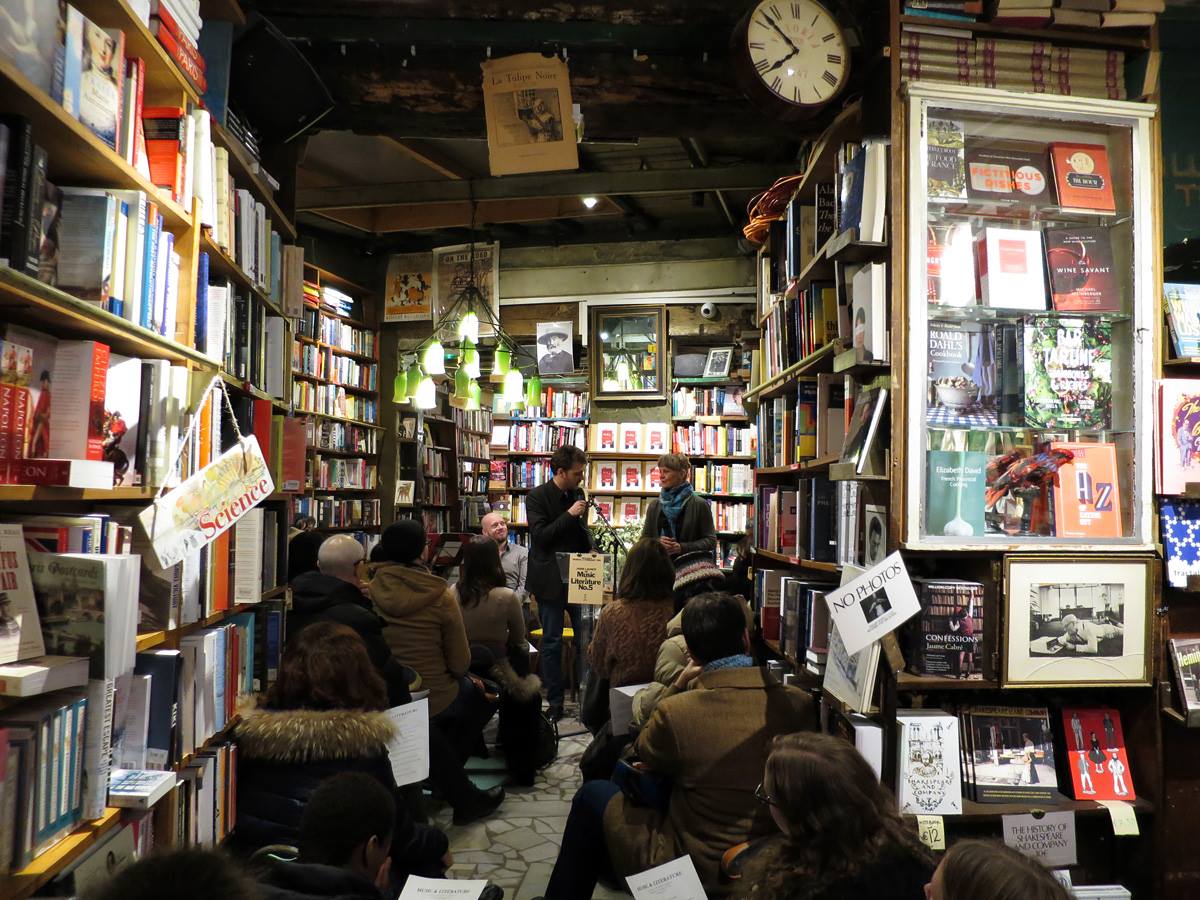

THE Paris LAUNCH OF MUSIC & LITERATURE NO. 5: shakespeare & co. / 2 feb 2015

Fresh off its launch at the Nordic Embassies in Berlin, Music & Literature brought a uniquely varied program to the storied Shakespeare & Company bookstore in Paris on 2 February, complete with live musical performances, readings, discussions, and remembrances—and with it all a friendly, intimate, and thoroughly literary atmosphere. A few people who happened to attend both events remarked afterward that the Paris event was “different from Berlin”—and it does indeed seem that each edition of the publication, once born and out in the world, begins leading several lives; while the programs vary from city to city, every event brings the featured issue to life in a way that remains true to the spirit of the celebration, appreciation, and close examination found in its pages.

Camilla Hoitenga opened the evening with a transfixing performance of Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho's Couleurs du vent for solo alto flute. A longtime friend and collaborator of Saariaho (she jokingly refers to herself as Saariaho's “muse” within the volume), Hoitenga clearly carries a deep understanding of the music. The piece was described as an exploration and history of breath—and indeed, as Hoitenga's breath moved between her body and the flute, I caught myself wondering where the woman ended and the instrument began, and whether that was a question with an answer.

Audun Lindholm pays tribute to Stig Sæterbakken.

Norwegian author Stig Sæterbakken, whose work is also featured in the latest edition of M&L and who passed away in 2012, was then introduced by Audun Lindholm. Opening with anecdotes from those who knew him, including Karl Ove Knausgaard, the man recalled was not only as an immensely talented writer but a tireless advocate for other Scandinavian authors. Lindholm himself seemed to regard Sæterbakken with a kind of tender reverence as he wove together stories of Sæterbakken's life, descriptions of his work, and a reading of “Some Autobiographical Notes” to form a portrait of a writer caught in the tension between hope and despair.

M&L co-editor Daniel Medin then took to the podium to read from Jan Steyn's translation of Graal théâtre by Jacques Roubaud and Florence Delay, which was followed by a reading of the French original by Delay herself. The piece served as inspiration for Saariaho's 1994 violin concerto of the same name; the connection between the play's combination of whimsical inventiveness and emotional depth and Saariaho's distinctive style was readily apparent.

Florence Delay reads from Graal théâtre.

This example of the interplay between music and literature so characteristic of Saariaho's work provided a neat segue for Aleksi Barrière's reading of her essay “My Library, from Words to Music.” The selection, which discusses Saariaho's creative process in moving from words to sound and back, was ideal for a journal titled Music & Literature, and gave enriching context to the musical performances. Hoitenga followed by playing Laconisme de l'aile for solo flute, which incorporates recitations of excerpts from Saint-John Perse's poem L'oiseaux throughout.

Attention subsequently turned to conductor Susanna Mälkki, who was interviewed by Barrière. Mälkki premiered Saariaho's oratorio La Passion de Simone in 2006, while Barrière recently produced a chamber version of the same. Mälkki's description of her first encounter with Saariaho’s Petals for cello and electronics in 1994 and her conversation with Barrière concerning their respective relationships with La Passion de Simone lent a personal dimension to the discussion of Saariaho, giving voice to the experience of working with her compositions in an intimate way.

Camilla Hoitenga performs the music of Kaija Saariaho.

The night's final reading came from Can Xue's “Dust,” translated from the Chinese by Annelise Finegan Wasmoen and recited by Daniel Medin. The piece, a touching avant-garde reflection on identity and relationships narrated by a speck of dust, fit perfectly with the tone set by the preceding performances and discussions of Sæterbakken and Saariaho as well as the unique situation of the event itself. As Medin narrated the convergence and dispersion of the dust particles, I couldn't help but consider the gathering of largely transient expatriates, closely packed in a Parisian bookstore, celebrating art in its many forms of translation.

Hoitenga concluded the evening with Dolce Tormento for solo piccolo, which Saariaho composed for the musician as a birthday gift in 2004. The piece features Petrarch's Sonnet 132, whispered into the piccolo in a sort of hushed, harsh incantation—the overall effect is one of emotional and spiritual intensity, at once otherworldly and somehow chthonic. As the piece neared its end, hovering somewhere between silence and sound, Hoitenga spoke almost clearly: “Sí dolce, Sí dolce.” How sweet, I thought. How sweet.

Left to right: Daniel Medin, Ariel Starling, Audun Lindholm, Susanna Mälkki, Aleksi Barrière, Florence Delay, Camilla Hoitenga, Laura Keeling.

—Ariel Starling

All photographs courtesy of Shakespeare & Company Bookshop