Kintu

by Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi

(Kwani?, June 2014)

Reviewed by Bwesigye bwa Mwesigire

Kintu, according to the Ganda, came to Uganda with his cow and lived as the first person there. From the sky came Nnambi, a beautiful woman, and she saw Kintu with his cow in the plains of Buganda. She was with her brothers, all from heaven, where their father, the creator, lived. Nnambi fell in love with Kintu and decided to marry him. Her brothers insisted that the creator had to consent the marriage, and so Kintu and Nnambi were taken to heaven. After the creator tested Kintu by setting impossible tasks—eating enough food for a hundred people, splitting rocks with an axe, fetching water in a woven basket—he assented and told Kintu and Nnambi to return to earth secretly, in order not to attract the attention of one of Nnambi’s brothers, Walumbe (Death). The next morning, on their way to earth, Nnambi remembered that she had left behind some grains for her chicken and so she went back. Walumbe immediately found her and insisted on following her. Despite her attempts, Walumbe clung to her and in this way death came to earth and has tormented humanity ever since.

This legend is encoded in the title of Kintu, a historical novel by Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi, which won the 2013 Kwani? Manuscript Prize. Kwani Trust launched Kintu in Kampala in June and even now, in December, the leading bookstore in the city can’t stock enough copies. The book is literally flying off the shelf. This is odd: most Ugandan bestsellers are also successful around the entire world, but Kintu is hard to come by outside East Africa. Makumbi says that she knew that her book would be hard to sell to Western publishers. “Europe is absent in the novel and publishers are not sure British readers would like it,” she told Aaron Bady of The New Inquiry. “I knew this when I wrote it. I was once told, back in 2004, when I was looking for an agent for my first novel, that the novel was too African. That publishers were looking for novels that straddle both worlds—the West and the Third World—like Brick Lane or The Icarus Girl but I went on to write Kintu anyway.”

The book’s crime, for which it is being punished by the Western publishing world, is its apparent snub of postcolonialism. But Makumbi has really not snubbed postcolonialism. As Aaron Bady says: “the point is not that colonialism didn’t happen, or was inconsequential; her point is that colonialism wasn’t the only thing of consequence that did. Colonialism is a thing that happened, and can be taken for granted. But other stories are worth telling, too.” That is enough a snub, perhaps, for the provincial Euro-centric publishing scene.

Makumbi’s novel turns its attention from those usual tropes of postcolonialism to what I would call African contemporaneity, or African contemporaneousness, to borrow Achille Mbembe’s word. This contemporaneity is manifest in Ugandan religious practice, for example. Again, talking to Aaron Bady, about African Christianity, Makumbi says:

So now traditional [indigenous beliefs] are written, not oral, there is baptism and traditional priests even perform wedding ceremonies. To me as an author this present is an incredible moment. We are witnessing syncretic processes of African culture, as a result of clashing with Europe, is in the process of reorganizing its structures by absorbing what is relevant from Europe, by discarding redundant aspects of its past, and by rejecting certain aspects of Europe that do not suit it.

As Kintu makes clear, “there is such a thing as African contemporaneity that is not mimicry of European culture nor is it a re-imagination of an African past.” Kintu reveals that this African present is affected by many factors, colonialism being just one and not at all the major influence. I am convinced that Africans are more driven to self-invent than to mimic Europeans. And as we see through Kintu, they creatively interpret their past (non-colonial if we must add) to understand and shape their present and future.

The casual Ugandan reader would pick up Kintu out of curiosity as to how Makumbi retells the Kintu legend. And, too, Kintu is said to be the name of the first Kabaka ruling the ancient kingdom of Buganda. “Kintu,” then, is a deeply historical word familiar to the novel’s Ugandan readers. Hardly any local reader could have expected the novel to be about our contemporary lives in a postcolonial world where colonialism is merely an event in the past, an event that does not define us and our interpretation of our present as our pre-colonial past does. But even the prologue is shockingly contemporary. Makumbi takes us to Bwaise in 2004: a slummy part of Kampala, famed for rampant flooding whenever it rains. Kintu, here, is not the legendary Kintu, a figure of the creation myth, but the last name of Kamu Kintu, a man who is murdered in an act of mob justice. He is accused of stealing because he has new gadgets in his shack, and a mob immediately finishes him off. This man seems to bear little relation to the half-understood family tree at the beginning of the book, and the wide-ranging table of contents, but perhaps the book will come back to the Kintu of history.

Book I does take us back in time, but the Kintu we go to is the Ppookino—the Ganda ancient title for governor—of Buddu province in 1750. Our Kintu Kidda adopts a Rwandan child that he accidentally kills while on his way to see the Kabaka in the capital. He does not bury the child properly, and Kalema, the dead child, makes this known to him in a nightmare while he rests at the Kabaka’s palace. It is a secret that Kintu almost unwillingly chooses to keep, attracting a curse from Ntwiire, Kalema’s biological father. Kintu Kidda’s story ends in tragedy. With our eyes used to postcolonial tales that usually bring in some White savior to save the day, I will admit that this particular hope kept me reading. But Makumbi has no intentions of telling the story from a Eurocentric perspective.

The history of most of Africa, of Uganda is usually told from the point of contact with the White explorer, missionary, and colonizer: a stretch of time from the late 1800s to early 1900s. At Makerere University, Uganda’s premier institute of higher education, the Ugandan constitutional and political history curriculum starts with the agreements the British signed in the early 1900s with the various monarchies that now form Uganda. But Makumbi takes us back to 1750, to a depiction of life before the White man. These scenes are not as we have seen them elsewhere—nasty, brutish and short—but respectful and respectable. Makumbi humanizes this life. It is reminiscent of Achebe’s Arrow of God, the novel most Africans, Makumbi included, identify as the best of Achebe’s non-White–influenced texts.

But Makumbi completely incises the White invasion and brings the story forward, in Book II, to the year 2004. With this new section, Bwaise is out of view and we are now in the mortuary at Mulago hospital, Uganda’s derelict national referral hospital, where Kamu’s body has been taken. The second book begins in the sub-town of Mmengo, where Suubi Nnakintu—whose last name noticeably echoes Kintu’s—lives. Ganda clans have specific names that distinguish members of one clan from another. Because Kintu Kidda is the patriarch of this clan, the name Nnakintu indicates that she is a “daughter” of the clan. This matter of lineage becomes a guiding thread through the novel; here, Ntwiire’s curse is very present in Suubi’s life despite all her creative re-inventions of her self.

On the face of it, Christianity has supplanted many of Uganda’s indigenous religions. Yet the contemporary practice of Christianity in Africa suggests that the religion has ceased to be European, despite its invasion through the hands and words of Africa’s colonizers and missionaries. In her interview at The New Inquiry, Makumbi said of Christianity in Africa that

[it now] seems more like an indigenous religion of Africa than a western import. I have seen Africans on the streets of Manchester trying to re-Christianize the British! This is how seriously Africa takes Christianity as its own. But at the same time, indigenous worship in Uganda is at the moment imbibing Christian elements in order to survive total annihilation by Christianity.

Ugandan readers, then, would not be surprised to find that Kanani Kintu, a radical born-again Christian at the core of Kintu’s third book, still bears the Kintu curse. He and his wife Faisi bear twins—an important sign of the curse. Then, although he and his more fanatical wife excommunicate themselves from their larger family, their twin children commit incest and a child is born of the sin. And this is the catch: these holier-than-thou Christians decide they will create a story that “some Munnarwanda” impregnated their daughter. They use the family curse myth as an escape from the shame of having failed to Christianize their children properly. And they take the daughter to their heathen relative till she gives birth.

In many ways, Makumbi shows us how colonialists and postcolonial theorists probably over-estimate Europe’s contemporary or historical influence on Africa. Despite the various modes of European expression, contemporary Africans frequently return to something beyond colonialism to explain their situations or even solve their contemporary problems. As Bweeza says: “He calls me, the English way, to distance unwanted relatives. But blood speaks.” There is also a conscious sense of power in being able to accept or reject colonial ideas. Bweeza rejects Christianity while her brother Kanani accepts the same. The result is a mélange of Christianity and heathenness, a chaos that can be understood and explained by the overarching concept of African contemporaneity.

One cannot help but sympathize with Kanani and Faisi’s children. They suffer the consequences of a conflict between their parents, and end up resenting their parents. This is where Makumbi’s keen understanding of contemporary Ugandan society and its contradictions shines. More often than not, we defend ourselves and our actions rhetorically. We express our pain in words. Indeed one of the twins explains the depth of their pain calmly:

“Have you ever sat on a bus and listened to your mother confess to strangers, to being a slut, to abortions and to killing innocent children? Have you ever sat in a school chapel with the whole school present listening to how your father started his sinning career with stealing eggs, then chickens, progressed to bestiality and graduated to raping women?”

Makumbi’s focus on contemporaneity is also visible from yet another Kintu, Isaac Newton, whose actions fill the fourth book. (If this review talks about Kintu’s structure more than usual, it is only because each of its books is so radically different, and sheds a new light on the issues Makumbi is investigating in her fiction.) Although Makumbi has decided to follow a particular family’s story, located in a particular part of the kingdom, in Uganda, and we know how big Africa is, her characters and she as well are aware of the world in which they live, without being representative. We learn that Katanga, where Isaac Newton spends his childhood, “was so named by Makerere University students. To them, the valley was as rich in female flesh and cheap alcohol as Katanga Valley in the Congo was in minerals.” Isaac’s story is, as they call it in several African countries, one of “grass to grace.” In many ways he represents the complexity of class in contemporary Uganda by working hard and going from living in the Katanga slum to working with a telecom company.

Throughout Kintu, but especially in this story, Makumbi manages to resist clichés and stereotypes in favor of realistic complexity. Marx’s analysis of class, for example, can’t describe how Miisi (who we meet in Book V), educated in Russia and at Cambridge, with a daughter in the army, loses a son (the Kamu we met in the prologue) to mob justice in a slum where he dwells. The extraordinary fluidity of classes, and subsequent ease in moving both upwards and downwards, is another element of African contemporaneity that bypasses the colonial moment. Attempting to explain this forces us to understand how African self-imagination is more important than colonialism in shaping the African present and future.

Makumbi is keen on fully fleshing out the lives of her characters and indeed the story of Uganda, Buganda, and Africa. As a result, the novel offers its reader more food for thought than explicitly postcolonial literature about Uganda would suggest.

For many years now, people in the Western world have remembered at least one thing about Uganda: Idi Amin. Kintu weighs in: “The British said that Amin killed his son Moses and ate his heart but Moses’s mother returns from Europe to Uganda and says that her son is alive in France.” Much has indeed been said and written about Idi Amin, most of which paints him in a less than positive light. Few non-Ugandan readers, for example, would have even heard of The Other Side of Idi Amin, a book by a Ugandan businessman arguing that Idi was also good for the country’s business class as he looked down on direct foreign investment and preferred providing incentives to local businessmen to expand their businesses. Miisi, disenchanted by the poor state of university education at Makerere, decides to resettle in the village. There, he learns, some Moslems and other villagers are still nostalgic about Idi Amin’s days. “The problem with Amin was not that he killed people; who hasn’t? Amin’s sin was that he killed the untouchables—the educated. Where Amin killed an Archbishop, Obote killed a hundred peasants. Did the world cry out?”

The complexity of African contemporaneity, outside colonialism and postcolonialism, is not something that has been explored by many contemporary novelists. As Achille Mbembe has written in his provocative On the Postcolony,

In Africa today the subject who accomplishes the age and validates it, who lives and espouses his/her contemporaneousness—that is, what is “distinctive” or “particular” to his/her present real world—is first a subject who has an experience of “living in the concrete world.” She/he is a subject of experience and a validating subject, not only in the sense that she/he is a conscious existence or has a perceptive consciousness of things, but to the extent that his/her “living in the concrete world” involves, and is evaluated by, his/her eyes, ears, mouth—in short, his/her flesh, his/her body.

The Ugandanisms in Makumbi’s English also attest to this focus on the contemporary Ugandan experience. Halfway through the book, we see “blood crying out for its own” and, a few pages later, we observe a conversation common to Ugandans: “Go die your own death, rich dog. We’ll die our own.” The way these expressions are thrown in the prose indeed represents their normalcy. Later on, Suubi says something I have heard spoken but never written, about Kanani: “Preaching the word of God in this place is like ordering porridge in a bar.” There is a vast field outside postcolonialism for exploring and explaining African contemporaneity, Makumbi shows us, and her novel helps us to find its interconnection and inseparability from Africa’s non-colonial past.

Makumbi’s concerns in the novel, although set in historical contexts, are astonishingly contemporary. The sore topic of homosexuality is manifested through a gay character in the 1750s Kabaka’s court. The current Pentecostal wave in Uganda, too, is uncomfortably present. As is HIV/AIDS. And traditional Ganda spirituality and psychology. The painful issue of child sacrifice. Mental health troubles—exacerbated by the deplorable state of modern-day mental health facilities in the country. Murder by mob justice. Inequalities in the country. But Makumbi is not preaching, nor is she seeking pity for her characters. Colonialism’s advent is absent from her book, and by implication it is absent from any explanation of Uganda’s problems today. Instead, her novel shows us how contemporary Africans can define themselves and find solutions to their contemporary challenges by looking to history. When they go back in time, to find “where the rain began to beat them,” to borrow Achebe’s words, they do not necessarily focus on the contact with Europe as the point where the rain began to pound them. The Kintu clan goes back 250 years to o Lwera (somewhere between Kampala and Masaka in present-day Uganda) where the patriarch of the clan is buried.

Makumbi refuses facile conclusions. Yes, she shows us the whole clan coming together in the final book, as they seek to erase the curse through rituals, but we never learn whether the curse actually goes away. The book brings several myths so thoroughly to life that we can almost believe them, but it also hints at truths so hardly credible we might confuse them for myths. In many ways, the book itself and its mythic use of suspense punishes us, like Miisi, “for knowing and refusing to know.”

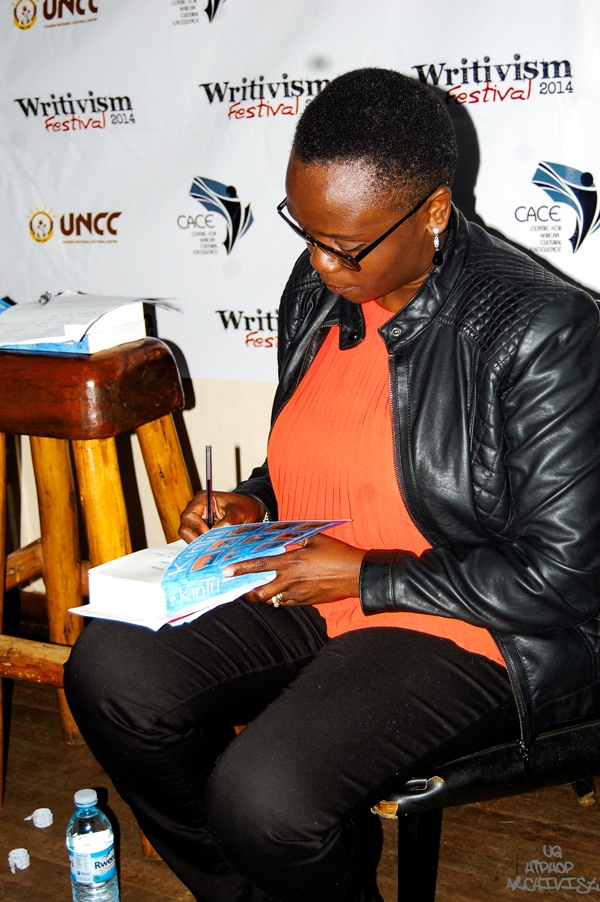

Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi signing copies of Kintu at the Writivism Festival in June 2014. Courtesy Writivism.

Today, Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi lives not in Uganda but in Manchester, England, with her husband and son. From this unquestionably Western perch, she is fiercely championing the cause of African contemporaneity. Her next novel, titled Nnambi for now, may well be the breakout that this overly Eurocentric world needs. There is hope that writers based on the not-so-dark continent can now see how vast the field of African contemporaneity is and follow Makumbi’s lead. She is currently working on a collection of short stories, three already published, one forthcoming in 2015 (one of them won the Commonwealth Short Story Prize 2014), all about migration from Uganda to Europe. They feature characters that “publishers were looking for, [that] . . . straddle both worlds—the West and the Third World,” as Makumbi had been told by that literary agent. From Kintu, Makumbi shines the light on the potential of African contemporaneity as a tool and sphere for illuminating the present and future African condition. Privileging colonialism and European modernism, even when based physically in the West, is a choice that African intellectuals make thus writing themselves out of relevance to continental Africans. There is a wide audience on the continent eager to read stories that center on their lives, their contemporaneity. Is it any surprise, then, that copies of Kintu have been, and will keep on, selling out in Kampala and across all of Uganda and the African continent?

Bwesigye bwa Mwesigire teaches at Makerere and Uganda Christian University. His work has appeared at This is Africa.me, Kalahari Review, Saraba, Chimurenga Chronic, and Munyori Literary Review among other places. He lives in Kampala.