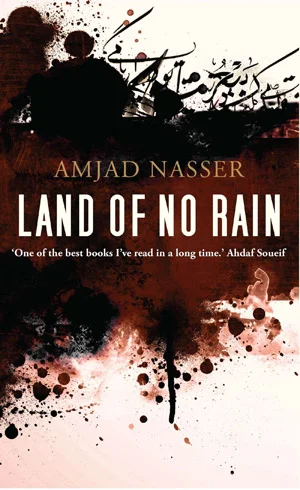

Land of No Rain

by Amjad Nasser

tr. Jonathan Wright

(Bloomsbury Qatar, June 2014)

Reviewed by Hilary Plum

It was not until reading Amjad Nasser’s exceptional novel Land of No Rain that I considered just how close the phrase “second person” is to “the double.” In second-person narration, the “you” threaded through the syntax of a novel demands that the reader occupy a life she must pretend is her own. Reading works written in the second person often feels like overhearing someone’s conversation with, or instructions to, herself. In the case of this novel, that premise has been, as it were, doubled: the “you” addressed throughout has, or is, a double. In Nasser’s intricate, mesmerizing prose, we readers become someone we’ve never been, while our protagonist confronts the self he no longer is.

“Here you are then, going back, the man who changed his name to escape the consequences of what he’d done,” the novel begins, and its premise is this: the protagonist, Adham Jaber, is—“you are”—a poet and journalist who is returning to his home country, Hamiya, after a long exile made necessary by his political activities. Most recently he has resided in the City of Red and Gray, through which a terrible plague has just swept; he escapes, though perhaps not with his health. In Hamiya he will encounter his double, Younis al-Khattat—his former name, the name under which he wrote poetry in his youth, and from whom it seems he divided upon departing his homeland. This version of himself has remained within its borders, and has, we are told with a wink, “contracted a mysterious disease that froze his appearance as he was when he was twenty, with the same interests and powerful emotions.” Adham Jaber is the pseudonym under which the protagonist published “articles and biographies” and pieces in a local newspaper that his conservative friend might call “allegations or fabrications about Hamiya and its characters.” The border between fiction and fact, literature and journalism, is, it seems, always contested: they are never one, but never two.

In the tapestry of this novel, proper nouns have been unstitched or obscured; hints of fable appear in their stead. The City of Red and Grey would seem to be London; Hamiya resembles Jordan. Adham and Younis were one but are now divided, even conflicting. Similarly, the world of the novel seems at once to resemble and not to resemble our own—a through-the-looking-glass world in which the reflection is both alternative present and real past. As Adham flees his homeland for the City of Siege and War and the City Overlooking the Sea (seemingly Beirut and Cyprus), along with fellow organization members who have tried to assassinate the general ruling their homeland, his exile is that suffered by many dissidents in recent decades. If you turn toward Wikipedia, you might learn that, indeed, the name Amjad Nasser is a pseudonym, and perhaps some of Adham/Younis’s life—a Jordanian writer who has long lived abroad, often working for Palestinian organizations—is like, or not too unlike, the author’s own. (In a particularly sinister echo of this novel’s doubling, Nasser was recently refused entry to the US for a planned reading tour: according to some sources he has the same name as someone on the terrorism watchlist.) “Hamiya is a real place,” we are told, “to the extent that places are real in the lives and imaginations of those who live in them”—here the imagined is as real as anything, and the real only as real as imagination can bear.

Such a light fictionalization of setting is not an uncommon strategy, but in Nasser’s hands it becomes especially elusive, richly challenging. The world and its reflection are so nearly identical that we readers want to locate each correspondence and each deviation—as if in any novel, any life, one could sort the real from the imagined. As we read, we keep searching out the real-life counterparts of Nasser’s people and places, driven by curiosity and the dutiful reader’s desire not to miss a reference. In this way Land of No Rain provides a distinctive case study in reading world literature, since as a reader of the English translation—I do not read Arabic—I know that many of the allusions that I experience as a mystery to be solved may be transparent to a reader in Arabic. The history that I have to look up might be well known by, let’s say, my double reading the original novel: she might know right away who this or that poet resembled, or just when the novel had deftly rewritten history. For a contemporary American reader, then, Nasser’s novel offers a supplementary gift: we must imagine Hamiya, the City of Siege and War, and the City Overlooking the Sea as they are described here, as places that may exist beyond the reach of our knowledge. We must accept this wisely fabulist telling of history as, literally, our own (since this all happens to “you”), without countering it, blow by blow, without overwriting it with the American narrative that has been expressed militarily in the region for decades now.

Nasser is known for his distinguished work as a prose poet, and the back and forth between Adham and his past often refers to debates over form in contemporary Arabic poetry. While readers of English may not have concrete points of reference for this conversation, the meditation is nonetheless stirring. (Indeed, a number of passages in the novel—whether concerning literature, calligraphy, or just episodes in the protagonist’s life—have a beautifully private quality, a refusal to explain themselves completely that is refreshing to encounter in an age of “accessible” fiction.) What is at stake in these aesthetic debates is always also political, always caught up in how people survive day to day. Just as, in this novel, we come to see how the existence of the double, the protagonist’s division from himself, has allowed him to mourn and to bear witness to a life he could not live. “As if to be incomplete was the way things really were,” our protagonist says at one point; he’s speaking of his father’s calligraphy, but the sentence resonates. Perhaps we each may need to split from ourselves to survive the violence of history: each self bearing witness to the other, each enduring what the other would not. This conflict, this sundering, is never merely personal, but perhaps a true reflection of the world we live in—as Adham reminds us, reflecting movingly on the failures of the leftist politics to which he once committed his life:

You didn’t start with the idea of two worlds that are always separate, always in conflict and that never meet, but from another concept, a concept of history as the arena for power, social classes and exploitation, regardless of skin color, brain size, religion, or whether one is circumcised or writes right to left. The concept with which you came to the city was a different idea you call internationalism. Now it’s called utopianism. Your concept has been shaken by the collapse of the models that tried to put it into practice, by the obsolescence that afflicts ideas just as it afflicts the real world, and by the fact that the journey grew longer and longer.

What was once a vision of the international is now mere utopianism; what was once a dream of unity is now the reality of division: “What’s your stand on those young men with suicide belts, armed to the teeth against historical subjugation, thwarted aspirations and the decadence of the real world?” Nasser’s Land of No Rain is immanently contemporary, immanently “relevant.” Political engagement and disillusionment, long exile, the obsolescence of youthful passions, a life comprehended through literature—page by page we perceive the protagonist’s textured hope, nostalgia, and loss: “[A]t the time you could not imagine a future for Hamiya other than the one suggested by the signs of power and permanence that were evident then, just as you never imagined you would have interests that would take you far away from your family”—a deceptively simple statement of personal and political grief and regret. Throughout, Jonathan Wright’s translation has an echoing, slightly mournful rhythm that seemed to me a fitting achievement. “Because what happened happened, and I am no longer me”: this is a novel in which the once-was and the might-have-been are allowed to live again, or still, or never. We readers of English are fortunate that this extraordinary work is now ours to be haunted by: a mirror in which we may not see ourselves.

Hilary Plum is the author of the novel They Dragged Them Through the Streets (FC2, 2013). She has worked for a number of years as an editor of international literature, including as co-director of Clockroot Books, and serves as an editor with the Kenyon Review. With Zach Savich she edits Rescue Press's Open Prose Series. She lives in Philadelphia.