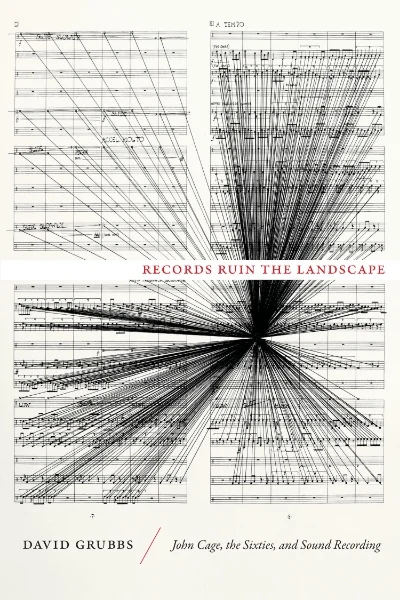

Records Ruin the Landscape: John Cage, the Sixties, and Sound Recording

by David Grubbs

(Duke University Press, March 2014)

Reviewed by Daniela Cascella

Consider a record, its fixity against all that passes and is alive: an object on the edge between timelessness and time, lending itself to repeated listening, close inspection, value judgments, even. An ambiguous object that at once contains sounds, yet is not only a carrier of sound. Consider the paradoxical coexistence, within the word “record,” of support and sound, medium and aural trace. Set against the contingencies of now, records can soothe and confound. Familiar yet ever new, they demand attention, make and undo memories, become subject to copyright and ownership. Precisely because of their fixity, they are stark reminders of our passing.

This puzzling yet seductive bundle of contradictions has been teasing artists, musicians, and writers since the advent of recording technologies in the late 19th century, prompting works at once diverse and haunting. In Breathless: Sound Recording, Disembodiment, and the Transformation of Lyrical Nostalgia (2002), a sophisticated study of the impact of early recording technologies on poetry, Allen S. Weiss observed that “sound, which had previously been deemed ephemeral and unstructured, is now the gateway to eternity”; the creative possibilities set off by recorded sound “are no longer limited by the binary logic of life and death grasped as an exclusive disjunction.” Records excite and disturb. Records frustrate and exhilarate. Records call for repetition. Records ruin the landscape: or such is the claim, famously made by John Cage, that gives the title to David Grubbs’s new book. Many musicians operating in 1960s American and European avant-garde and experimental circles shunned such a crucial and controversial element in our perception of music as recorded sound—most notably Cage and Derek Bailey, who stated that their music could only be experienced in full in ephemeral performance settings. And yet many of these musicians allowed their music to be recorded, as evidenced by contemporary releases as well as the numerous archival recordings that would appear decades later, first as CDs and then online. What are the implications of such aural revenants on music practice, on listening and understanding today? And how can the ephemerality of 1960s music performances be compared with another form of ephemerality, represented nowadays by the enormous quantity of audio recordings available online?

Cage disdained records as tied to dull professionalism and the constraints of “getting it right,” favoring instead a flux of sonic material embedded in the present. Bailey deemed records detrimental to improvisation because they encouraged the “endgame,” the display of style rather than the embodiment of performance. Both positions appear to Grubbs as problematical and exquisite riddles, not only because Cage did in fact release groundbreaking recordings such as Cartridge Music (1960), Indeterminacy (1959), and The 25-Year Retrospective Concert of the Music of John Cage (1958), and because Bailey founded his own Incus Records label. In his own experience as a musician, collector, listener, Grubbs has inhabited both ends of the terrain vague between performing and recording, and he therefore treads the tangled ground of his inquiry with an informed and nuanced approach, well aware that the categories of “record” and “performance” are not mutually exclusive, entailing diverse and intricate perspectives. In the Preface he chronicles the arc of his engagement with recorded and performed sounds, from his work as a high school fanzine editor receiving “objects set adrift, obscure recordings randomly encountered”—records that could be subject to repeated listening and, crucially, owned; objects that were “never only about music”—to his move to Chicago in the 1990s and his concurrent exposure to live improvisation gigs, hard to decipher and never asking to be deciphered. A revealing encounter with music by Morton Feldman led to a heightened awareness of the possibilities of sound within space; further reflections arose on the construction of a persona through the information released or withheld in a record.

“I was born in the late 1960s, and I often gravitate toward music created in that decade. Fundamental to my interest in music from this period is the challenge of understanding that part of the past that lies just beyond memory’s reach.” Records Ruin the Landscape unfolds in the tension between music performed in the 1960s, now past recall, and the effect of listening to records of that music today, as they reappear through the ebbs and flows of archival drifts and unofficial histories. But Grubbs does not take the 1960s as a chronologically confined focus. Because many recordings from those years only emerged decades later, and because many of us can only know that era through its recordings, the 1960s function like a prism, reflecting current concerns as they are heard again and rewritten in and out of their time, forgotten in lost and unreleased archives, resurfaced in reissues and online databases. The book’s compelling time-lapse element is exemplified by the case of Henry Flynt’s lost album I Don’t Wanna, recorded in 1966 but only released in 2004. As Grubbs embarks on a journey spanning traces, texts, interviews, facts, and fictions on Flynt, he observes how the album sounds so much of its time to our ears, despite going unheard at the time of its recording. “What does it mean to describe a recording as being of a moment in which it did not circulate? Conversely, what does it mean to describe previously inaccessible music as participating in a later moment in which it resonates more powerfully?” What does it mean for us many years later to access, through records, music that was intended to be experienced in the actuality of performance?

Ownership is a vexed question in these pages, as the circumspection about record releases expressed by some musicians seems tied to a tendency to steer and control their musical identities toward coherence. A telling example is the controversy over the tapes holding performances by the Theatre of Eternal Music/Dream Syndicate group (La Monte Young, Tony Conrad, John Cale, Marian Zazeela, Angus MacLise), claimed by Young as their sole author and owner. Unable to access those recordings, between 1987 and 1994 Conrad provocatively released seven works entitled Early Minimalism, reinventing a “lost” music untied to issues of ownership and uniqueness. As he constructs and performs an idea of Minimalism whose documentation had been made inaccessible, Conrad recomposes a missing past in a twist of time, against fixed histories carved in stone, power, and privilege of access: his gesture exacerbates the friction between records intended as absolute keepers of truth, and recording as the ceaseless re-making of identity through and despite incoherence and interference.

Though rife with details, Records Ruin The Landscape never unfolds as a drab compendium of facts: out of anecdotes, archival discoveries, and insightful interviews, other less explicit, profound lines of inquiry arise. An overarching issue is whether a boundary can be traced between the experience of music and what reaches out beyond music: between recording and evoking, between listening, remembering, and anticipating, between sound and what exists around it. Most crucially, the status of a record as a repository of truth is probed and shaken if put in relation to music ingrained in the time of its very performance. Is a record a partial trace, forever failing to hold an “original” event, a pale shadow dangerously mistaken for an origin, or is it possible to think of a record as an element of its own standing, not derived from a pure and perfect original and not constituting one in itself either, but rather existing in a flux of sounds, ideas, visions, and contributing to such flux and to our mutable understanding of music? How is history made, told, unmade, heard, or unheard through rumors and recordings, myths and murmurs, sounds and senses, the extra-musical into the musical and back? How are legacies, lineages, and traditions drawn? Grubbs has listened much and performed much, and won’t fall into the misleading path of binary oppositions. At one point he makes a remark about music “known far more by reputation than by actually having been heard”; and yet the very nature of listening as it seeps into the non-strictly-musical realms of desire, anticipation, imagination, social and cultural histories, is not only attached to music as an essential category. The extra-medium, the multi-medial can also be considered as pertaining to music; what circles, attacks, and erodes music defines it too. How is music described, by whom, which language is used, and how does this tap into the imaginary universe held by each? There is no one way of describing it, and music does not elicit one single answer. Although at one point Grubbs writes that music “should be heard. Or physically felt”—in other words, explanations are never enough—the stories he recounts in these pages also suggest that there is enormous potential in the slow reveal, in the less heard but unerring presence of what exists around records with no claims to explain them: scenarios of longing, anticipating, remembering, of listening further, performing further. As Pauline Oliveros stated in Robert Ashley’s music-theater piece Music with Roots in the Aether, there are times when “we hear descriptions…which are almost more valuable than the recorded document.” Such an imaginative, silent yet resounding, dimension may also be heard in the title of a series of electroacoustic pieces by Luc Ferrari, Presque rien (Almost Nothing), where “almost” embodies the charged imaginative space around sound more than any tangible record could.

As Grubbs writes of Cartridge Music, his longstanding involvement with Cage’s oeuvre is unmistakable. He does not seek for definitive interpretations but writes as a listener who is in turn prompted to perform—and between recording and performing, between records and landscape, he chronicles multiple and absorbing encounters with this album as a particular type of “formless music” that allows the listener to focus on something different every time. “Formless music” embraces chance, unforeseeable incidents, and all the traits of the given time of a performance, offering a way out from the recording as an absolute representational act: it happens, for example, in the recording of Concert for Piano and Orchestra included in The-25 Year Retrospective set, which features audible unease and audience disapproval. “Sound recording comes to us as a means of representing this extracompositional excess that is crucial to, for lack of a better term, music.” Such “extracompositional” excess locks the aural characteristics of a given time into the actuality of the recording. “It is precisely the nontextual elements, the in-addition-to-song, the external-to-composition, that are most thrilling about records.” As Cage laconically said, “we have more than just ears”—a statement echoed in Theodor Adorno’s remark, “every work of art is always more than itself. This is confirmed by the fact that even works in which all interconnections have been rigorously eliminated as in Cage’s Piano Concerto [sic], nevertheless create new meanings by virtue of that very rigour.”

Who is to make such interconnections other than the listener? In the essay The Prospects of Recording (1966) Glenn Gould foresaw the listener-as-composer. As the opposite extreme to Cage’s stance, Grubbs aptly mentions Gould, who disappeared from concert halls altogether in 1964 to devote himself to studio recordings. However distant, both Cage and Gould’s work outlined an idea of the electronic work as landscape, interwoven with the presence of listeners as significant, if elusive, players. In Imaginary Landscape No. 1 (1939), Cage used sounds produced by variable-speed turntables and frequency recordings exploring possibilities for music generated by non-conventional instruments: he highlighted the mediated nature of sound recording by placing it within live performances, and made space for the unsettled listeners to inhabit them as living characters. Gould, on the other hand, produced The Idea of North (1967), a radio piece of constructed ethnography where identity appears ever mutable, where the merging of voices and field recordings out of time allows each listener to tune in from within their time. “The inclination of electronic media is to extract their content from historic date,” he wrote, postulating the record as untied to the specificity of chronologies. As Grubbs evaluates Cage and Gould’s positions on recorded sound, a landscape in which records are listened to for both their embodied and imaginary qualities opens up in all its rich and mutable potential.

The infinite horizon in the imaginary landscape of recorded sound draws the final boundary of Records Ruin the Landscape, and it is necessarily a porous one: a threshold of transience, not closure. In the last chapter Grubbs analyses two online audio archives, the Database of Recorded American Music (DRAM) that offers audio files on a paid, stream-only basis, and UbuWeb, with its policy of free access and free downloads. Growing, potentially unlimited online audio archives constitute a significant counterpart today to the collection-as-stockpile crucial to Jacques Attali’s observations expressed back in 1977’s Noise: The Political Economy of Music, where music collections were tangible symbols of knowledge, of time spent by an individual collecting music. As online resources have been making available large quantities of archival recordings, some of them never intended for release, and are in most cases the results of a collective effort of uploading and sharing, Grubbs wonders why some things are deemed representative and some not, and how we may understand music from the 1960s through records made available in such manner. He avoids lumping considerations together in concluding pronouncements, especially in the face of the diversity of forms that an umbrella term such as “online music archive” can contain: blogs, record label outtakes and side releases, artists’ own archives or estates, university libraries, temporary curated databases, and more. Most significantly, records kept in online audio archives may no longer be objects, and as Grubbs crucially suggests that mediation is central, a major question arises with regard to metadata—locked on-screen in the case of files streamed on the DRAM website, detached in the case of files downloaded from UbuWeb—and once again, in connection with the extra-musical. He underlines the necessity to address how online archives are browsed and to ask which cultural, individual, and collective dynamics are at play. As digital archives favor plural histories no longer centered around masterpieces, perhaps the ephemeral and transient nature of sound cherished by Cage and Bailey is regained: listening to the records in online audio archives becomes more distant from the diktats of interpretation, as it connects and transmits protean microcosms of myriad audio files.

The last few years have seen a rapid increase in the production of and market for vinyl and cassette releases, more often than not in limited, collectable editions: perhaps a missing chapter in this book would have considered this pervasive phenomenon, a vital counterweight to the diffusion of online archives. Most importantly, such limited releases are often tied to specific scenes, networks, communities, and so are those around digital ones. In a book that began with a quote by John Ashbery, “the resulting mountain of data threatens us,” the closing questions might be not about a threat but about navigation: how do we make, connect, and distribute knowledge, how do we know? Within and beyond the specificity of media, how do we make, connect, and distribute sounds, how do we listen? Certainly Grubbs listens intently: one of Records Ruin the Landscape’s distinctive characteristics is the palpable sense of an argument unfolded in the present and attached to the author’s singular and absorbing encounters with records; as present as it is singular, such argumentation may unfold in lapses that are not always seamless, but doubtlessly dynamic. We are never too far from appreciations sparked off by Grubbs’s personal engagement with the music—where “personal” is by no means a synonym of “casual,” but on the contrary grounds and tightens the vast array of arguments possible when it comes to researching, thinking about, and collecting sounds from the 1960s. Grubbs treats himself as a case study, which makes perfect sense in connection with a range of research material that would make very little sense if casually glued together without an involved glance and ear. Throughout the book he does tackle central theoretical issues such as the role of chance in music and art and the tricky notion of “the archive,” but the driving force behind these pages, and what makes them a welcome and vitalizing addition to the growing field of sound studies, is never only theoretical: the burning core of this book is the palpable excitement and restlessness of an audiophile urging his readers less to join the dots and envisage conclusive scenarios on paper than to go and browse, to get absorbed in search trails and to be exhilarated by whatever is found there, whether anticipated or unexpected. Records Ruin the Landscape is a book where the insightful scholarship and the enticing outline of an argument function like sounding boxes for all the music that you will be driven to discover and rediscover after reading it. Not only a vital challenge to rethink online collections, but a resolute prompt to listen to them.

Daniela Cascella is a London-based Italian writer who works with sound, literature, and language. She is the author of En abîme: Listening, Reading, Writing. An Archival Fiction (Zer0 Books, 2012). Her new book F.M.R.L. Fragments, Mirages, Refrains and Leftovers of Writing Sound will be published by Zer0 Books in April.

Banner image credit: Flickr user Josef Stuefer