In some perhaps not-so-distant future, when lab technicians in Google glasses are scanning back over the four- or five-hundred-year oddity that was the literature of Western modernity, the work of Enrique Vila-Matas may at least survive as a testament to its protracted death throes. Vila-Matas’s novels practice a peculiar form of high-literary bricolage, grubbing around in the rubble of the modernist tradition and finding there just enough material to cobble together a tragicomic monument to their own obsoletion. His four previously translated works represent a series of elegant self-negations: A young writer suffers from a form of “literary paralysis” that leaves him unable to experience reality except through analogy to the books he has read [Montano’s Malady]; a despairing author, unable to overcome his writer’s block, instead sets to work on a history of literary “Bartlebys” who have renounced writing [Bartleby and Co]; a young would-be writer travels to the Paris of his modernist heroes in search of inspiration, but finds there only confirmation of his own belatedness [Never Any End to Paris]; a retired publisher travels to Dublin on Bloomsday to mourn the death of “the Gutenberg Age” [Dublinesque].

“Only from the negative impulse, from the labyrinth of the No, can the writing of the future appear,” writes the narrator of Vila-Matas’s 2000 work, Bartleby and Co. If literature’s negative impulse was once directed at a world that it critiqued or transfigured from a position of relative detachment, in Vila-Matas’s work that negation has turned inward, and is directed against literature itself. His novels resist their own status as literature, but can only do so by confronting it and taking it as their inescapable subject matter. This is not quite the playfulness of postmodern metafiction, though it is certainly metafictional and in some ways playful. Instead of postmodernism we might instead call it post-literature. The trope of the funeral for literature employed in Dublinesque is one that might be applied to Vila-Matas’s work as a whole, underpinned by an irony that is closer to the gallows humor of Samuel Beckett or Thomas Bernhard than it is to the exuberance of John Barth or Thomas Pynchon. Modernism was always among other things the pursuit of forms of expression that stand outside of and contradict the logic of an increasingly commodified culture, which packages experience into easily assimilated units of meaning. If postmodernism is in some sense a liberation from the prohibitions of modernism and an embrace of commodity culture, Vila-Matas’s work is a tragicomic confrontation with modernism’s dwindling conditions of possibility in the era of postmodernity.

Now, with the publication by New Directions of two new English translations—the 1985 novella A Brief History of Portable Literature, and Vila-Matas’ latest creation, the semi-fictional 2014 work The Illogic of Kassel—we have further evidence of the ingenious contortions and acts of literary cannibalization with which Vila-Matas has contrived to keep a fading tradition imperfectly alive. With A Brief History of Portable Literature English readers are introduced to the work that helped establish his reputation in continental Europe; a slim and enigmatic novella in which Vila-Matas imagines the brief and eventful history of a literary secret society, The Shandies, whose members include Walter Benjamin, Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, and Georgia O’Keefe.

A Brief History of Portable Literature

by Enrique Vila-Matas

tr. Anne McLean & Thomas Bunstead

(New Directions, June 2015)

Written some fifteen years before the first of his previously translated works, A Brief History of Portable Literature nonetheless crystallizes many of the peculiar virtues that have gained Vila-Matas a small but devoted following. The novella is saturated with a version of the “literature sickness” that afflicts the narrator of Montano’s Malady, preventing him from experiencing the world in any other form than in and through literature. It is composed entirely of made-up anecdotes about the real writers and artists who form its subject matter, evoking a suffocatingly close yet nonetheless strangely unattainable past when literature was apparently a spontaneous way of life rather than a self-conscious charade or Luddite affectation. Portable literature, we are told, is “a kind of literature that is . . . characterized by having no system to impose, only an art of living. In a sense it’s more life than literature.” And as throughout his work, Vila-Matas’s narrator is left on the outside of this way of life, nose pressed to the window, separated by some unspecified historical chasm or fall into inauthenticity.

Yet far from being doom-laden or portentous, what marks it as one of Vila-Matas’ singular creations is the tone of undecidability, pitched somewhere between eccentricity, rambling conviviality, and thinly veiled despair. Vila-Matas does not simplistically valorize an authentic past at the expense of an inauthentic and inferior present. The past itself rather serves as a sustaining illusion, subjected to all manner of idealistic falsifications. Rather than being a book about modernism or a theory of the death of literature, A Brief History of Portable Literature is really a book about the quintessentially postmodern condition that Fredric Jameson has referred to, following Flaubert’s literature-sick heroine, as bovarisme: a condition in which life is inescapably mediated by literature, yet can never fully measure up to it. The narrator of A Brief History of Portable Literature submerges himself in a fantastical construction of a Utopian avant-garde to ward off the reality principle of an intolerable present. Yet rather than doling out some tedious high-cultural condemnation of the contemporary, Vila-Matas ironically undercuts himself at every turn, transforming fake literary trivia into a bizarre and ludic comedy that nonetheless never quite shakes off its underlying melancholy.

The Illogic of Kassel

by Enrique Vila-Matas

tr. Anne McLean & Anna Milsom

(New Directions, June 2015)

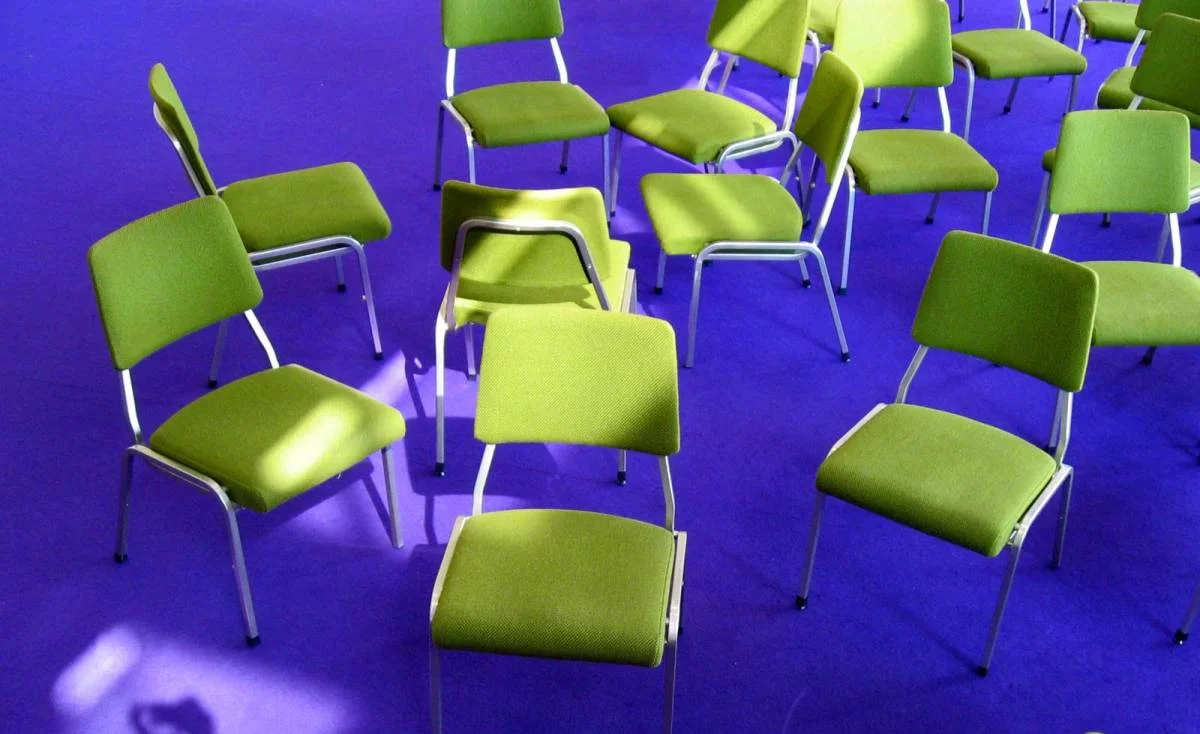

If A Brief History of Portable Literature sees Vila-Matas creating a semi-fictitious avant-garde, in The Illogic of Kassel, written nearly thirty years later and set in 2012, we read about him going in search of a real one. The narrator, a version of the author himself, is invited to the legendary Documenta art festival in Kassel, Germany, to take part in a performance art installation in which he and various other noted authors take turns sitting down and writing amidst the patrons of the Dschingis Khan restaurant [“the most miserable-looking Chinese restaurant I’d ever seen in my life”]. What follows is a mixture of mock reportage, theoretical musing and bizarrely comedic falsification, as Vila-Matas seeks to gain “an approximate vision of contemporary art’s situation at the beginning of the twenty first century,” but instead finds himself ever more deeply mired in confusion.

The artworks at Documenta generally consist of installations, which are not “just for looking at, but could also be lived”; Peter Sehgal’s This Variation, in which the observer walks into a pitch-black room; Ryan Gander’s The Invisible Pull, an artificial breeze that circulates around a gallery space; Susan Phillipsz’ Study for Strings, in which participants listen to a haunting piece of music at the same stretch of platform at which many victims of the Nazis waited for the trains that would transport them to the death camps. Given his rigorous cultural pessimism, and the inauspicious-sounding prospect of the spectacle at the Dschingis Khan, we might expect Vila-Matas to approach Documenta as further evidence of the contemporary cultural malaise. Yet for all that his works can be read as monuments to the tragic demise of some prelapsarian ideal of autonomous culture, what is going on in The Illogic of Kassel is far more strange and intriguing than a straightforward satire or condemnation of the contemporary avant-garde. Indeed, far from approaching the conceptual artworks at Kassel in a spirit of high-modernist disdain, Vila-Matas’s narrator seems to be determined to persuade himself that he is experiencing some sort of renewal or epiphany. Early in the novel he tells us:

I detested all those ominous voices very common in my country that displayed their supposed lucidity and frequently proclaimed fatalistically that we were living in a dead time for art. I guessed that, behind this easy tittering, there was always a hidden resentment deep down, a murky hatred towards those who occasionally try to gamble, to do something new or at least different.

Yet we can never quite believe that Vila-Matas believes himself. Indeed, he immediately undercuts this view with a notably less affirmative revision:

I had systematically forbid myself to laugh at avant-garde art, though without losing sight of the possibility that today’s artists were a pack of ingénues, a bunch of Candides who didn’t notice anything, collaborators unaware of their own collaboration with power.

Rather than resolving to answer this question one way or the other, the novel plays potential positive and negative readings of the Documenta avant-garde off one another without fully foreclosing either, creating an ever-thickening fog of ambiguity. Far from being a diatribe against contemporary art, then, The Illogic of Kassel turns out to be an absurd and enigmatic comedy, recounting an avant-garde art-inspired epiphany that to the untrained eye looks a lot like a nervous breakdown.

The layers of irony through which Vila-Matas’s “real” views are withheld and deferred would seem to mask a genuine ambivalence. The problem seems to lie somewhere in the very nature of the aesthetic experience on offer at Kassel, which the narrator finds both regenerating and strangely isolating. The interactive and conceptual artworks at Kassel do not create determinate meaning or socially significant representations, but instead provide a venue for a subjective and completely user-specific experience, epitomized by Sehgal’s darkened room, which serves to cocoon the viewer within his own private subjectivity. The nature of the narrator’s experience of the artworks is therefore totally individual and private, a product of whatever contingent and non-repeatable frame of mind he happens to be in when he experiences them. As one of the organizers tells him, “Art is neither creative nor innovative . . . Art is art, and what you make of it is up to you.” Rather than standing apart from the world and negating it through the elaborate formal procedures of high modernism, the contemporary avant-garde has succeeded in collapsing the division between art and life:

Had I not learned from Tino Sehgal, Ryan Gander and Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller that art is what happens to us, that art goes by like life and life goes by like art?

Yet this dissolution of art into life would seem to lie at the heart of Vila-Matas’s ambivalence, even if he mostly tries to repress it through his increasingly desperate and self-deluding professions of optimism. If art becomes indistinguishable from the world, does it not risk swapping its critical energy for a socially impotent and ultimately status quo-affirming pluralism? Does art not thereby risk colluding with a social order that wants to teach us that it too is not a binding or repressive structure, but is simply whatever we choose to make of it?

Torn between these positive and negative polarities, Vila-Matas’ narrator descends ever further into his own private eccentricity. And indeed, the longer he remains in Kassel, the more impossible it seems to become for him to communicate with anyone else he meets. This non-communication unfolds through a series of increasingly absurd interactions with the various festival organizers, whom he manages to alienate one by one with his incomprehensible musings. His stay at Kassel culminates in a rambling and inchoate public lecture, which the festival director describes as “Martian”; a remark which, like everything else at Kassel, is open to interpretation:

She didn’t specify whether she meant “admirably Martian” or just Martian, but, since my joy and frenzy for life was ongoing, I chose to take it as a compliment.

If the experience of Kassel provides Vila-Matas with imaginative stimulation and helps shake him out of the vicious circle of his cultural pessimism, it seems to do so at the price of isolation and self-alienation. But then again, maybe the self too is merely another of those modernist shibboleths; perhaps we are all merely what we choose to make of ourselves?

“To say that literature is dead is both empirically false and intuitively true,” writes the British novelist and philosopher Lars Iyer in a “literary manifesto after the end of literature and manifestos.” Iyer names Vila-Matas, alongside Bernhard and Roberto Bolaño, as one of the “very few” writers who have “grasped the dire nature of our current literary moment,” trailing in the wake of an authentic literary culture whose gestures we can only ape with varying degrees of self-consciousness and bad faith. We might add to these names the likes of David Markson, Gerald Murnane, Eduard Levé, W.G. Sebald, Gabriel Josipovici, the J.M. Coetzee of Elizabeth Costello and Diary of a Bad Year, Ivan Vladislavić’s The Loss Library, and perhaps even Karl Ove Knausgaard, whose My Struggle is to some extent a struggle with its own impossibility. Much of the most vital contemporary writing, at least in the Western world, has taken as its starting point a confrontation with the condition of cultural belatedness, in which the gestures of both realism and modernism can only be repeated as farce, and one suspects that the authentic expression of the current age may lie outside of literature, perhaps even outside of culture, altogether.

One does not need to subscribe to the fatalistic “death of literature” thesis to see that the conditions of contemporary culture present a grave challenge to the vitality of the novel. Though Vila-Matas mostly deals with intuited effects rather than detailed cultural diagnoses, the causes are manifold and everywhere apparent: the exhaustion of viable forms of expression and the sense that everything has been done before, and better; the canonization of experimental art and the neutralization of its disruptive energy; the relentless commodification and banalization of mass culture; the LinkedIn-ification of the world and the incorporation of writing into the great neoliberal conflagration of bourgeois self-promotion; a paralyzing sense of belatedness, inauthenticity and farcical repetition; and perhaps above all, a sense of arbitrariness and contingency, of forms and styles being merely choices made from a range of neither more nor less valid alternatives.

And yet for all of this, Vila-Matas continues to write prolifically. With the publication of A Brief History of Portable Literature and The Illogic of Kassel, Vila Matas’s English-language corpus has now grown from four to six, still only a fraction of the twenty-two novels that make up his oeuvre in Spanish. Like the capitalist system in whose shadow it took up residence, modernism has always existed in a state of permanent crisis. We may stand inexorably in the wake of the true avant-garde, but for now Vila-Matas and others like him continue to find new ways to alchemize negativity into strange and exhilarating forms of life.

Danny Byrne is a PhD student in English at Brown University.