Whispers

by Frank Denyer

Frank Denyer (voice, instruments), Elisabeth Smalt & Benjamin Gilmore (violins), Kiku Day (shakuhachi), Juliet Fraser (voice), Dario Calderone (bass), Pepe Garcia Rodriguez & Bob Gilmore (percussion)

The Barton Workshop

Jamie Man (conductor)

(Another Timbre, March 2015)

Reviewed by Paul Kilbey

The softer you whisper, the closer other people have to listen. This is true enough in everyday conversation, but powerfully illustrated by the British composer Frank Denyer, who notes of the Plains Pokot, a people of East Africa, that they sang more “potent” songs more softly, “and very significant texts, such as those of the cattle songs composed by each individual adult male, were sung in a whisper.” To catch the most important song, you have to listen hard. Denyer’s own music—especially “Whispers,” the composition which lends a new CD devoted to his work its title—requires similarly close attention. Murmurs, unvoiced whistling, tapping, an offstage violin that barely surfaces in the mix—listening to this, barely possible unless you strain to hear it, feels like an intrusion, eavesdropping on something strange and unusually intense.

Another Timbre, the record label on which Denyer’s CD appears, has whispered its way through close to a hundred discs. Based in Sheffield, England, and run by its founder Simon Reynell since 2007, it specializes in what it terms “post-Cagean” composition as well as improvisation. Though the label has started to offer downloads on some releases, the focus seems to be firmly on physical objects: this is music to seek out, invest in, and make time for. There is almost no way to listen to Another Timbre albums without downing distractions and devoting substantial attention to them—“The music is intended to be quiet and is best played at a low volume,” reads a note on a marvellously tranquil double CD of Morton Feldman released last year. Many other discs, Denyer’s among them, are not only quiet but filled with substantial silences or near-silences, which set the occasional louder noises that do emerge—such as those in Denyer’s tellingly titled “Two Voices with Axe”—into stark relief. Though almost all the albums seem to stem from divergent compositional or performative practices, they require something close to a common listening approach, one engaging listener and performers alike with the silence as well as the sounds that surround the music. A notable success for Another Timbre a couple of years ago was a six-CD set entitled Wandelweiser und so weiter, which epitomized the label’s approach by bringing the sparse music of the elusive Wandelweiser collective, doyens of the “post-Cage” scene, together with that of a number of other composers, improvisers, and performers, showing common threads: there isn’t quite a “school” of new music represented by the label, but there is a coherent aesthetic, one in which close, committed listening is imperative. You can’t just put these albums on your phone and listen casually, in the background: the music vanishes if you do that. Frequently, one longs for the anechoic chamber of John Cage’s famous anecdote.

But Cage’s point was that real silence is an impossibility. With or without an ax, there are always intrusions. Even in the chamber, shut off from any extraneous noise, one hears oneself (Cage heard his circulation). The closer you listen to Another Timbre’s discs, the less self-contained the music sounds. You unwittingly contribute when you move in your seat, when you hear a car passing outside. Each listen is unique, and it’s you as the listener who makes it what it is—conceptually, through interpretation, but also literally, through the noises you contribute.

Extinguishment

by Fraufraulein

Billy Gomberg (bass guitar, electronics), Anne Guthrie (horn, electronics)

(Another Timbre, March 2015)

Extinguishment, a recent Another Timbre release by the Brooklyn-based duo Fraufraulein, uses quite different musical means to create a similar sort of effect. Three hypnotic pieces of between 11 and 16 minutes combine improvisations on bass guitar (Billy Gomberg) and French horn (Anne Guthrie) with electronics, recordings from their live shows, and field recordings. These are blended with great subtlety—it’s barely ever clear where one element ends and another begins—and they add up to something gently mesmerizing, a soft wash of sound often reminiscent of what you might hear walking idly about in a quiet town. Two-thirds of the way into the first track, “convention of moss,” some sort of choral folk-music concert gradually comes into focus and then fades away amid the sound of heavy rain. Soft bleeps and the murmur of a crowd of people vaguely suggest a shopping center—to me, anyway. It is a tapestry, within which one element is the listener, eagerly finding imagined patterns, overinterpreting, even.

This is Fraufraulein’s first album with Another Timbre, although Guthrie has been involved with a couple of the label’s online projects. Improvisation has been an important part of the catalog since its first release, Tempestuous, by the trio The Contest of Pleasures, which was recorded live at the 2006 Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival. Improvising musicians who have worked with the label multiple times since then include violinist Angharad Davies and harpist Rhodri Davies (her brother), veteran experimental pianist John Tilbury, and various members of Wandelweiser including Jürg Frey (of whose music another album is currently in the works) and Johnny Chang. But no less extensive is Another Timbre’s involvement with more conventionally composed and/or notated music: recently, the musicians of the group Apartment House, especially cellist Anton Lukoszevieze and pianist Philip Thomas, have featured on a number of albums. There are discs devoted to the music of a diverse miscellany of composers, often but not always British: among them, Laurence Crane’s pensive, curiously tonal chamber music; Martin Iddon’s subtly demanding explorations of performance techniques; and the wonderfully drawn-out Vessels, a solo piano piece of 76 minutes (and one dynamic level) by Bryn Harrison.

Despairs Had Governed Me Too Long

by Skogen

Magnus Granberg (piano, clarinet, composition), Angharad Davies & Anna Lindal (violins), Leo Svensson Sander (cello), John Eriksson, Erik Carlsson, Petter Wästberg, Henrik Olsson (percussion), Ko Ishikawa (shō), Toshimaru Nakamura (no-input mixing board)

(Another Timbre, February 2014)

Not that the divide between improvised and “composed” music is in any way clearly defined. The several recent discs by Swedish composer, pianist, and clarinetist Magnus Granberg and his group Skogen demonstrate this particularly well—hard to categorize, they are clearly improvised to some extent, but the material is delineated such that it’s also correct to talk about a composer. These albums are first of all credited to the performers—Skogen on the recent Despairs Had Governed Me Too Long and Ist gefallen in den Schnee; the related smaller group Skuggorna och ljuset on Would Fall from the Sky, Would Wither and Die—and the composition credit is unobtrusively embedded among the list of performers: “Magnus Granberg—piano, clarinet, composition.” Cage found free improvisation distastefully ego-driven, but this is an approach to music-making that combines improvisation’s sense of freedom with a very sincere egolessness.

Would Fall from the Sky, Would Wither and Die

by Skuggorna och ljuset

Magnus Granberg (clarinet, composition), Anna Lindal (violin), Leo Svensson Sander (cello), Erik Carlsson (percussion), Kristine Scholz (prepared piano)

(Another Timbre, March 2015)

I haven’t heard Ist gefallen in den Schnee—the CDs are sold out—but the other two discs feature entrancing, subtle performances. They draw on limited material, each time derived obscurely from other people’s music. Despairs Had Governed Me Too Long comes from a John Dowland lute song, “If my complaints could passions move,” and Would Fall from the Sky, Would Wither and Die comes from the jazz number “If I Should Lose You.” From listening it’s not apparent what bearing the source material has on the outcome, but the pieces both have a strong enough identity of their own that this question—like the question of precisely how the improvisatory and composed elements come together in performance—fades into the background. Rather than addressing these issues, what the albums do is present a long stretch of material, all entirely consistent and even, and yet also formally unpredictable, such that each listen conjures up different shapes and moods. If there is a consistent sense of melancholy running through them, it is the same sort of melancholy to be found in Feldman: a calm, subtle tug at the heartstrings, melancholy through beauty.

It’s Feldman even more than Cage who haunts these albums, I think, which makes the recent double CD of his work—Two Pianos and other pieces, 1953–1969—particularly apt. This is both an important release for any Feldman fan (while everything has been recorded before, a few pieces are quite seldom heard, and all recorded superbly) and an excellent overview of what appear to be Another Timbre’s key aesthetic concerns. Not only does it present long stretches of careful, gentle, unpredictable music; it also achieves its effect through, or in spite of, a variety of means, since the scores require the musicians to play in a number of different ways.

There are no graphically notated pieces here, but all experiment in their own way. Between Categories (1969) and False Relationships and the Extended Ending (1968) are both written for two small instrumental groups, notated one above the other in the score. But most of the time the two groups have different tempi, so that they move through the score at different paces and may even be pages apart from each other at any given moment. Just occasionally, the ensembles do come to line up again vertically on the page—surprising moments of revelation for the performers, though probably not for the listeners, who could hardly know. It reminds me, vaguely, of how it must have been to sing from partbooks in the medieval or renaissance period, with no available score: the otherworldly thrill performers must have felt as cadences or other moments of coordination suddenly appeared.

Two Pianos and other pieces, 1953-1969

by Morton Feldman

John Tilbury, Philip Thomas, Catherine Laws, Mark Knoop (pianos), Mira Benjamin, Linda Jankowska (violins), Anton Lukoszevieze, Seth Woods (cellos), Rodrigo Constanzo, Taneli Clarke (percussion), Naomi Atherton (horn), Barrie Webb (trombone)

(Another Timbre, November 2014)

On the other hand, Piece for Four Pianos (1957), a better known composition, makes moments of (score-based) coordination technically impossible: each pianist moves through the same single page of music slowly, but at their own pace. As a concept this is on a par with 4'33" for its simplicity and clarity; it is a perfect expression of what makes so much of Feldman’s music, and plenty of the music it has inspired, so remarkable. Especially in the hands of what is more or less a supergroup of Feldman pianists—Tilbury, Thomas, Catherine Laws, and Mark Knoop—it’s remarkable. The piece is four interpretations, four subjectivities, expressed simultaneously, with total independence yet also with such complete mutual respect that what the piece really sounds like is not a long, strange canon, but rather one super-composition in which the four performers together improvise the phrases and pauses that emerge, unpredictably, from their material. Though this double album has just one recording of Piece for Four Pianos, the two CDs are bookended by different takes on the conceptually identical Two Pianos (also 1957), played glassily by Tilbury and Thomas; a tribute, as the pieces are themselves, to the beautiful manifoldness of interpretation.

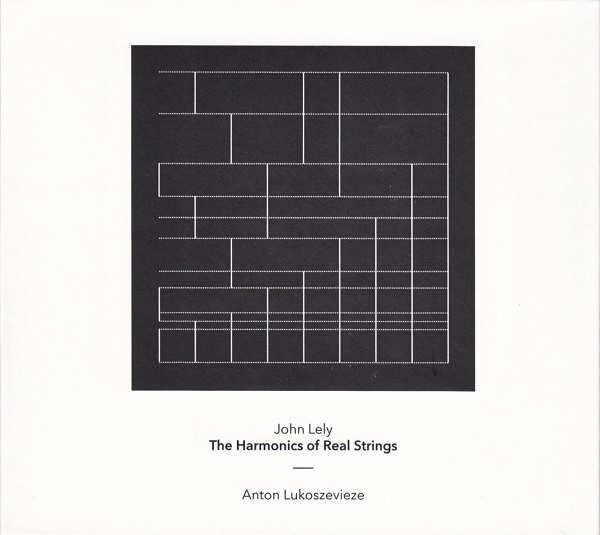

The Harmonics of Real Strings

by John Lely

Anton Lukoszevieze (cello)

(Another Timbre, November 2014)

The other post-Cage/Feldman thread in recent composition is of course minimalism. No surprises that Another Timbre has not hosted any of the minimalists who have tended to dominate the popular discourse over the years—but The Harmonics of Real Strings, a piece by British composer John Lely recorded here by Anton Lukoszevieze on cello, nods its head to “first-wave” minimalism. The composition consists of an instruction with something of the simplicity of La Monte Young or James Tenney. The performer plays one long, very slow glissando, sliding a finger gradually up a string—but pressing down only gently, to produce harmonics. Lukoszevieze realizes the instruction four times on the album: once on each string of his cello. What is entrancing is how unexpectedly this simple idea plays out. Despite the regularity of the performance, the sound produced is irregular, unpredictable. It is both completely simple, and as complex as you let it be. If you find it boring, then let’s follow Cage’s advice, and listen again, and again, until it’s interesting. It’s up to you how many times you listen.

Who is listening, though? All these albums, really, are whispers. Not that they’re designed to exclude people—it’s just that to hear them, you have to lean in and pay attention. The quietness is structural. And a small audience is surely inevitable for music which, quite literally, doesn’t make much noise about itself. So much contemporary music tries to explain itself loudly: through huge orchestras, bloated percussion sections, and maddeningly abstruse programme notes, as if all this baggage were necessary to keep people interested. And, indeed, we are all shouted at very loudly even when we aren’t listening to music: walking down the street, we are pitted against reams of exclamation-pointed imperatives—Buy this! Do that! The real challenge is to listen to as little of it all as possible. All of which makes deliberately quiet music a rare thing: something that doesn’t demand your attention, but nevertheless repays it if you give it. Who’s listening? People who’ve decided to concentrate on it.

Everyone who does decide to do this, needless to say, listens differently. So much so, in fact, that evaluating the quality of the music on these albums seems almost to miss the point. These albums don’t set out to prove the talent of the composer or performer; that isn’t what they make you think about. There is of course a huge amount of technical skill informing all these albums—perhaps especially on the Feldman album, which finds Thomas, Tilbury, and their fellow performers completely in tune both with each other and with Feldman. The Granberg albums are performed with amazing fluidity as well, and Lukoszevieze’s feat of endurance on the Lely album is quite something. But the thing is, there are such large spaces left between the notes on all these albums that really, they are as good as the number of thoughts they set off in the listener’s mind.

I can only speak personally, then. For me, Extinguishment and Would Fall from the Sky, Would Wither and Die are the most consistently rewarding of the above-mentioned albums, alongside the Feldman—they’re the ones that draw me in the most, the ones I most want to re-listen to and try to make sense of, perhaps because they always sound different when I put them on. I find the Lely disc remarkable, but not as diverse. And the Denyer puts me on edge—but then, I like to lie back calmly and immerse myself in listening, and Denyer deliberately works with awkward sounds that stick out, like a half-voiced, breathy whistle and an ax. I get jumpy. You might not. Or you might enjoy getting jumpy.

What I mean is, there are always going to be hits and misses, and with a label like Another Timbre, the hits and misses will necessarily vary substantially from person to person. The Denyer album misses, for me, because it doesn’t fit with how I like to listen, but I wouldn’t want to try and force that view on anyone else. I was glad to read the late musicologist Bob Gilmore’s liner note, which was a typically eloquent explanation of just how much he clearly got out of listening to Denyer’s music (he co-produced the album too). I tried to listen to it like I suppose he did, but I couldn’t. Clearly, he listened in a different way to me. How much less interesting everything would be if we all listened the same way.

Paul Kilbey is a writer on music and culture based in London. He works at the Royal Opera House and has written for publications including Tempo.