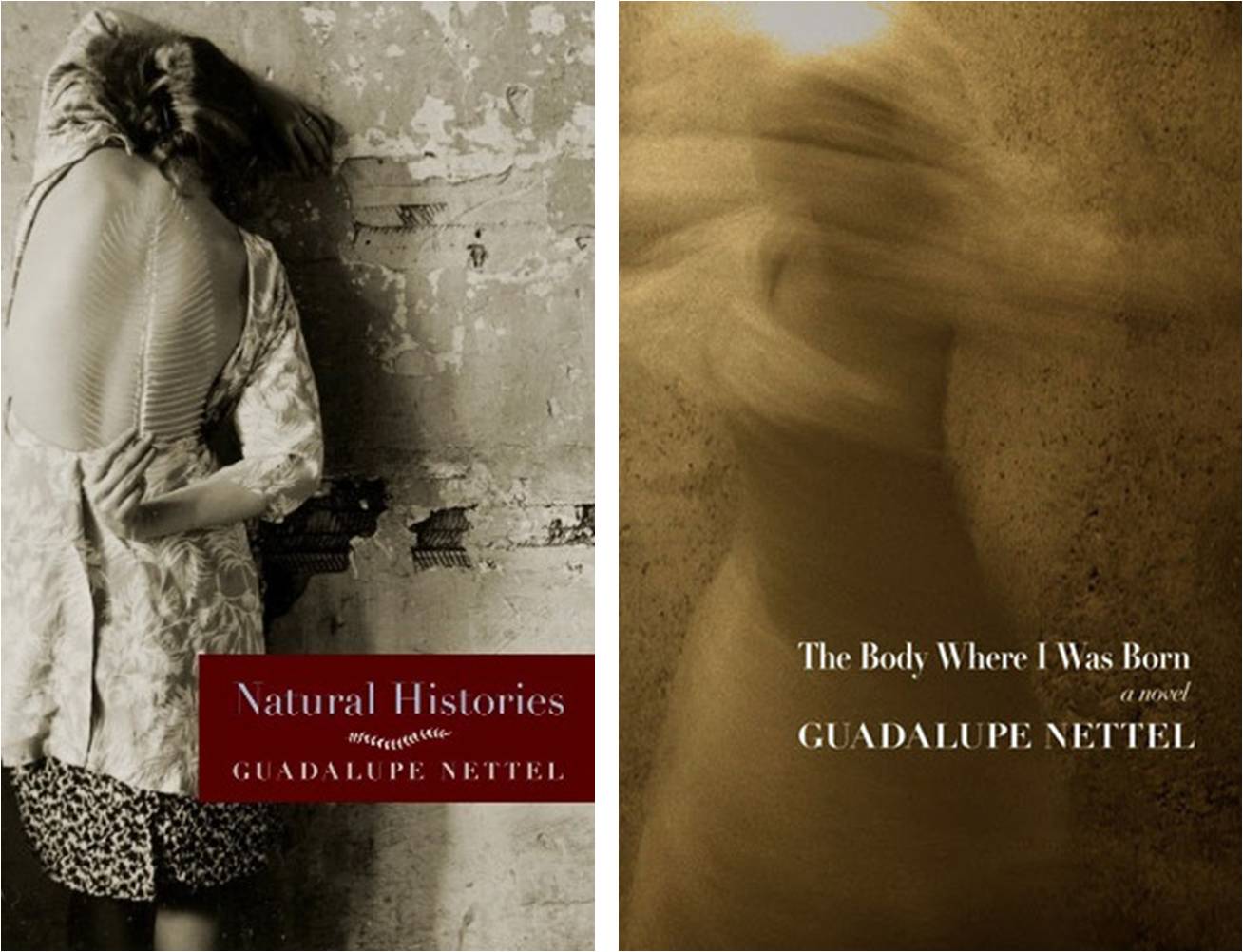

Natural Histories & The Body Where I Was Born

by Guadalupe Nettel

trans. JT Lichtenstein

(Seven Stories, June 2015)

Reviewed by Tyler Curtis

It’s been a fruitful decade for contemporary Mexican writing, and the English-speaking world has become more attentive to our Hispanophone literary neighbors. Heavyweights like Sergio Pitol and Juan Villoro eked their way north to due praise, and Valeria Luiselli and Álvaro Enrigue are increasingly on the rise among Mexico’s beloved living exports. In this vein, J.T. Lichtenstein’s recent translations of Guadalupe Nettel’s short-story collection Natural Histories and novel The Body Where I Was Born stand out as some of the strangest and most sumptuous prose to emerge from this trend. Nettel is a linguist by training, and grew up between Mexico and France; appropriately her language, surely the product of a childhood of linguistic and cultural mobility, toes the line between the sympathetic and relatable and the radically bizarre. Both books—the former a series of encounters with animals, the latter a youth recounted in a therapist’s office—detail the psychological and even ontological degradation of familiarity between us as the world sees a greater propagation of bodies, movement, and cultural and economic encounters. The undercurrent of globalization permeates her texts, so it’s only appropriate her prose mirrors such proliferation.

Subsumed by a strange growth, the protagonist of Guadalupe Nettel’s story “Fungus” concludes, “Parasites—I understand this now—we are unsatisfied beings by nature.” The sentence transitions ever so slightly, ever so gradually from “it” to “we” in referring to the fungal infection, but the effect is glaring in retrospect. She contracted the infection from an extramarital affair, and it’s spread all across both their bodies. As her unrequited obsession continues to grow, so does the fungus, in a manner both horrific and tinged by humor (“My fungus wants only one thing, to see you again”), eventually becoming indistinguishable from the fabric of her desire. Like “Fungus,” each story in Guadalupe Nettel’s Natural Histories pairs its characters with unknowable creatures whose trajectories parallel the inevitable disintegration of their domestic comfort. On top of the fungal fever dream: betta fish exhibit strange behavior and fight savagely as a woman’s postpartum depression grows apace with her husband’s increasing distance; an exotic snake appears while a father longs for his ancestral homeland; a cockroach infestation reaches a head as a family reaches a new apex of madness; a pregnant cat births a litter, subsequently disappearing as a doctoral candidate aborts her pregnancy.

Nettel’s novel, The Body Where I Was Born, exhibits similar concerns and degenerative playfulness, and indeed it feels like an outgrowth or proliferation of what was seen in Natural Histories. On the surface, the novel is less surreal than the collection, certainly more informed by realism. But where the symbolism of animals and interpersonal/psychological deterioration is heightened in Natural Histories, at times even heavy-handed, The Body’s characters experience this spread much more organically. The novel’s narrative ecology seems more subtle, the familiarizing of difference (be it animals, or the protagonist finding herself among strangers in a new country) correlating directly with a degradation of familiarity in both empathy and language, among families, friends, and lovers.

Nettel’s ecology of longing is grotesque in the Rabelaisian sense. The Body Where I Was Born evokes both Bakhtin and Rabelais, and one of its starkest moments centers on the narrator’s aunt:

she was an exceptionally sensitive woman, a lover of the grotesque and the scatological, of Borges’s poetry, Rabelais’s novels and Goya’s paintings—invented a tale inspired by my surreptitious behavior, which she would tell us at night after reading from the children’s edition of Gargantua y Pantagruel.

In her stories, the body is literally open among animals and mycelium, and in The Body, physical marks and defects are points of both contention and camaraderie: “It was as if our strangest characteristics—my crossed eye, Blaise’s stature, and Sophie’s scar, to name a few—were actually markings we had chosen, like piercings or tattoos.” This is not to mention the way in which Nettel pits liberalized sexuality against the rise of post-sixties social conservatism: “That’s how, with the seventies in full swing, I joined the ancestral order of closet masturbators, that legion of children who rarely peek their heads out from under the sheets.” Nettel’s bodies are simultaneously open and closed off, and both the fear of and fascination with consummation is rife among her family and friends.

It is said that the extremely conservative turn taken by the generation to which I belong is due largely in part to the emergence of AIDS; I am convinced that our attitude is very much a reaction to the highly experimental way our parents confronted adulthood.

This is a clever play on the kind of carnivalesque, celebratory grotesque aesthetic so often picked apart by semioticians like Bakhtin and Kristeva. While the “true” (that is: original) grotesque according to the theoretical canon is gay and ambivalent, Nettel recognizes that the opening up of the body scared an entire generation into complacency under the hierarchies it sought to dismantle.

Nettel’s power structures aren’t inverted here so much as the text laments their reinforcement. Like dining on once-feared vermin, the status quo returns to normal, supremacies intact. This comes as a relief to some characters, but therein lies the tragedy. Elements of The Body are semi-autobiographical: the protagonist’s move to France, and fictionalized versions of Nettel’s peers, like Alejandro Zambra, make an appearance. The novel is framed in a therapy session, with the narrator looking back on her life. It’s a kind of anti-Portnoy’s Complaint; instead of foregrounding misogynistic solipsism, The Body focalizes feminine experience and the longing for empathy, and the attempt to break down physical and spiritual barriers, with varying degrees of success. As she confesses to her therapist in the final pages:

My own body that for years constituted my only believable link to reality now feels like a vehicle that’s breaking down, a train I’ve been riding all this time, going on a very fast trip toward inevitable decline.

In this way, the author conspires against her characters, their lives partitioned off by the very means that would grant access to a new world.

Nettel is well acquainted with the tradition at play here; she holds a doctorate from the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales in Paris, once home to Barthes, Derrida, and Lacan, to name a few. She appropriately toys with signification, not only with the grotesque poetics, but also with the otherwise familiar. Family turns strange on a dime, like in “The Snake from Beijing”:

The man standing in front of me had my father’s voice and face; he smelled like him and made many similar movements, but at the same time, something about that person made him a complete stranger to me.

In The Body Where I Was Born, the narrator’s desperate flight to her old home causes her to find that it’s become a home for the elderly, with a sign on the wall reading, “Learn to die and you will have learned to live,” a phrase that sticks with her into adulthood. What’s more, the 1985 Mexico City earthquake hits while she lives abroad, and, confused by the serenity of her French home, she wonders if the “past may have been utterly extinguished by little more than two minutes of terrestrial oscillation.” As signs are constantly in flux, Nettel shows us that the only reliable means to imbue a thing with meaning is the instance of beholding it: “Interpretations are entirely inevitable and, to be honest, I refuse to give up the immense pleasure I get from making them . . . I take comfort in thinking that objectivity is always subjective.”

Nettel’s success is both poetic and conceptual, and there are more that a few moments of linguistic sublimity that Lichtenstein triumphantly conjures into English. The translator is often successful, but not entirely. Like in many of the quotes above, both books shine when Lichtenstein can distill the author’s enchanting and frequently bizarre prose. But the language in Natural Histories isn’t entirely consistent, and at times it’s even awkward. Here’s a sentence from “War in the Trash Cans”: “When I came to their home my aunt and uncle received me with a mix of pity about the situation with my parents and apprehension about the way in which I’d been raised.” Many of Nettel’s sentences do feel a bit confounding and chaotic, as they’re meant to do. The translator did note the challenges she faced when translating the organic peculiarity of the Spanish prose, which ultimately earned Nettel Anagrama’s Herralde Prize for Después del invierno. Still, the translation is compelling, if structurally perplexing at times. The language does hit a stride in The Body Where I Was Born, which was translated after Natural Histories, the symbolism being much less overwrought, the structure much more fluid. And despite some inconsistencies with the language, both books signal Nettel’s exultant arrival to the English language.

Tyler Curtis is a writer and US Editor for The White Review. He lives and works in New York.