The Swan Whisperer

by Marlene van Niekerk

(Sylph Editions, July 2015)

Reviewed by Daniela Cascella

For some time now I’ve been reading The Swan Whisperer over and over as if under a spell, driven by the idea that what links the swan in the title and the words in the text is sound. The word “swan” comes from the Indo-European root “swen-”: “to sound.” And according to some versions of the legend, Orpheus was transformed into a swan after his death.

Words into sound, through a whisper. I try to stitch these elements together, then realize that probably the verb to use shouldn’t be stitch but say, or speak.

This is a tale of transmission, disappearance, and utterance, of writing as it hovers at the edge of language, trafficking with the ephemeral and the unreliable; challenging the primacy of the written text through a compelling reflection on flow and interference, rhythms and non-origin. A tale of listening as the rebeginning of writing; of people missing but resounding through words whose meaning is lost (or maybe it was never there completely): it has to be made anew every time. A story of speech emerged from and given back to birds, wind and water, a story of speech into landscape. A tale of writing as divining and impure continuity.

***

The Germanic word for magic formula is galdr, derived from the verb galan, ‘to sing,’ a term applied especially to bird calls.

-Mircea Eliade, Shamanism

Marlene van Niekerk likes to talks with owls. “The fellowship of breath,” the South African writer calls those birds in a short interview with The Guardian, on the occasion of her nomination for the International Man Booker Prize in 2015. The reference to breath leads me to recall the old meaning of the word “psyche” as air, an element connecting inner states with the sensuous world; and the ancient notion of birds as spirit visitors carrying the whispers and voices of the lost and missing ones, or of birds as originators of human language. In the same interview Van Niekerk mentions Wordsworth’s poem There Was a Boy, about a boy who talks with owls and then is lost in “a pause / Of silence such as baffled his best skill.” Tellingly she refers to Seamus Heaney’s reading of the poem in Finders Keepers. “Skill is no use anymore [to the boy/poet],” Heaney writes, “but in the baulked silence there occurs something more wonderful than owl-calls. As he stands open like an eye or an ear, he becomes imprinted with all the melodies and hieroglyphs of the world; the workings of the active universe […] are echoed far inside him.” The Swan Whisperer is also a story of voice dissolved into the landscape, transformed into a different substance and texture, different but present. It stretches the understanding of language into what is concealed or not yet heard, and farther out into the wild nature of landscape, until language becomes “the very voice of the trees, the waves, and the forests,” to borrow Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s words from The Visible and the Invisible.

Owls, writing, and birdsong. For the Koyukon people of Alaska the owl is the supreme prophet of birds: it “tells you things.” According to Vedic mythology, as I learn from Roberto Calasso in Literature and the Gods, “the meters […] turned themselves into birds with bodies made of syllables.” For the Kaluli of Papua New Guinea, as ethnomusicologist Steven Feld reports extensively in Sound and Sentiment, “‘bird sound words’” have “‘insides’” and “‘underneaths’”; they “alter the framing of interactions, moving them onto a plane where underlying feelings, emotions and thoughts associated with loss come to the listener’s mind.” Turned over, words show more than one side to themselves. A bird appears at a key point in Leonora Carrington’s The Hearing Trumpet, harbinger of transformation through the disruption of rational language: “Belzi Ra Ha-ha Hecate Come! / Descend upon us to the sound of my drum / Ikala Iktum my bird is a mole / Up goes the Equator and down the North Pole.” And in another story of unhinged language, Gert Jonke’s Awakening to the Great Sleep War, birds are seen as winged alphabet letters trying to arrange themselves “even when there’s not much to say.” Are syllables, alphabets, and hearing trumpets enough, to enable a subject to listen, record, write beyond the acquired channels of linguistic representation and transmission devices? The characters in this tale suggest otherwise.

The Swan Whisperer begins as a public address and ends with an incantation.

It begins as a formal lecture and ends, through various reports and erasures of utterance, on the edge of form.

Its pages hold words about getting lost and about to get lost.

Three characters in the story: the narrator, a creative writing professor called Van Niekerk, like the author (who places herself from the outset in a complex mise-en-abyme where person becomes character and back: the embodiment of a necessary Janus-like gaze spanning fact and fiction); a creative writing student the professor calls Kasper Olwagen (but is this his real name? We never find out) who is stuck in a writer’s block, disappears, and later contacts his teacher through various devices; and an elusive Swan Whisperer, encountered by Kasper on the canals of Amsterdam, who can communicate with birds.

The teacher is reluctant to read, the student cannot write, the Swan Whisperer does not speak—or prefers not to. They all appear to be undergoing different stages of a metamorphosis.

Kasper’s nickname is Xenos, outsider, stranger: to himself, and to writing. His story is reported through his teacher, who receives it in seemingly disconnected fragments: a 67-page letter, a book entitled The Logbook of a Swan Whisperer, sixteen 60-minute cassettes, sand. None of them hold any truth but complicate the jolted unfolding of the narrative: records, like the narrators in these pages, are unreliable, voicing erosion through time. The loci from which this story is written are not sites of stability, either. Kasper’s letter is sent from a hospital intensive care unit, Professor Van Niekerk writes from a shaken point of hesitancy. Out of such a condition of instability, of intensive care, the broken subjects in this tale of unwriting appear vulnerable: porous channels for quivering polyphonies, where every voice intimates that they’re using the tongue of another in an ongoing transmission whose origin is lost.

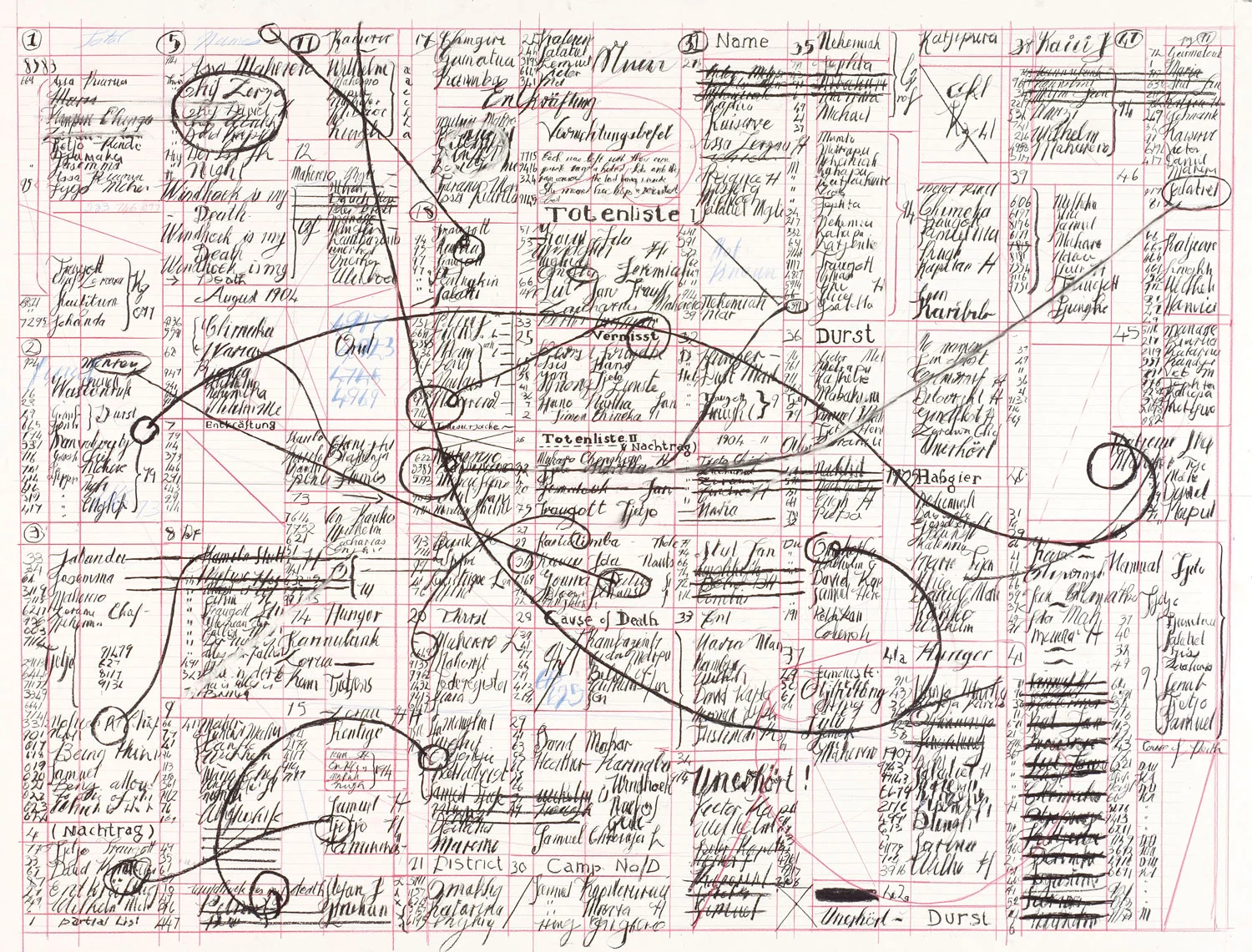

Broadcasting devices are also present—albeit fractured, partially erased—in the drawings by fellow South African William Kentridge interspersed in the pages of the Cahier. They point at the unpolished nature of transmission, and at the uncomfortable, damaged, violated site of writing. Erasure, in Kentridge’s abrupt brushstrokes, as much as in Kasper’s logbook entries, takes the form of black ink washes set against delicate calligraphy, or: the force of life and history as it interrupts and complicates polished forms of writing and reporting. What is testimony, what is transmitted and inevitably interfered with (because it is alive even when unspoken, silenced)?

Much in this story is unresolved, unexplained, untold. The actual documents are rarely disclosed and most of the narrative is half-guessed at or thwarted—and yet present on its own complicated terms.

Understanding does not come exclusively from texts as permanent marks: it is generated through listening on the periphery of canonical meaning, through speech that is sensuous, tactile like the ink, marks, and erasures of Kentridge’s drawings, or like the sand that the professor receives from her student by post. Speech prompts errors and astonishment, Kasper intimates while he morphs into a listening-speaking-writing enlandscaped entity beyond self. It must also voice absence, violence, and omission through dissonance. In this sense The Swan Whisperer is the necessary counterpart to Agaat/The Way of the Women, van Niekerk’s 2006 novel of inner polyphonies. While Agaat’s absorbing fullness, across more than 500 pages, overcomes the barriers of the narrator’s muteness with the noises of inner speech, The Swan Whisperer is a supreme synthesis of taciturn hints, its 37 pages alluding to records and reports where it’s never entirely certain who or what can be trusted, other than the materiality of words which demand to be heard and spoken. Agaat is a torrential unfolding of language in a multitude of selves and voices; The Swan Whisperer’s skeletal structure is that of a story within a story within a story told, mistold, spelled on the vapor on a windowpane only to disappear shortly after. Agaat is narrated by somebody who has lost her voice, is mute. The Swan Whisperer suggests we must make ourselves mute in our voices and adopt the voices of others, to enable a resounding flux of thinking-feeling to enter into writing. It does so by density rather than scale, disclosing connections in every word.

I can’t let go of The Swan Whisperer’s viscous materiality, its thick and fiery lava stream of correspondences drifting through my attention. It has the effect of a chant grasped beyond reasoning, an alchemic transformation that conveys dreamlike visions through a terse, poised language, in a disarming contrast of blurred states of mind and sharp rhetorical edges. At one point the professor encounters the phrase “tohoe wa bohoe” in Kasper’s logbook: first she dismisses it as nonsense, later she finds out that in Hebrew it means “formless void.” The appearance of Hebrew in Kasper’s undecipherable transcriptions seems to be a nod to the Enochian traditions of language divinely received, and to stories of angelic conversations. I begin to suspect every word is here for a reason, in a dizzying vertigo of connections and references that I’ve only begun to fathom, and that perhaps also includes all the numbers and the names precisely dotted all over these pages. The game of join-the-dots nevertheless leads to nothing: this story is not the clear outcome of a scheme or a hidden formula. The more I read it the more I sense, through its density and its frictions, that all its parts will never quite hinge, so close they are to the unruly tensions that exceed language and then claim to return to it in the most tangled arrangements. Through the filter of Kasper’s words and the Swan Whisperer’s spells the professor allows herself boldly and unapologetically to speak of magic and angels, as her character stages intermittent detachment and deep involvement with such entities, never apparently endorsed but certainly long frequented and deeply pondered. Perhaps this is what Kasper meant when he wrote that his story might be used for his teacher’s “dark designs.”

The text is punctuated with confrontations on writing, as the professor reports her discussions with Kasper, the conflicts between the roles of “an archivist” and “an aesthete,” between fact and fiction, the true and the beautiful. The breakthrough occurs when the tale ceases to preempt and critique itself, when its characters—and their readers—stop forcing themselves to understand. Kasper wants the Swan Whisperer to speak, as much as he wants himself to write, so he tries all the tricks, he tries to extract words by exposing him to terror, to the sublime, to romantic music. He even checks his mouth, and its ridges remind him of a harp—another Orphic symbol. He’s drawn to the Swan Whisperer’s ability to converse, although in another language: a skill he’s lost, and he can only regain, like Wordsworth’s boy, through learning to listen and to accept that taking part in a transmission means not always having control over it. He will begin to write when the recurring question, where does writing come from? is transformed into what and whom does writing come through?; when he is able to pass his experience onward, to someone else’s voice, no longer concerned with the choice between truth or fiction, but absorbed by the dissonance of their contrast. Kasper begins to write when he begins to care and to listen; when writing is no longer meant to be still, but is shaken by shivers of spoken words, sounds, relations, and rhythms. When are they heard, who or what whispers them to us, through us? Earlier in his story he had written, on a damp windowpane: “Perhaps my whisper was born before my lips”—a line from Osip Mandelstam, who once said that a poet is a stealer of air. Kasper breathes and writes through someone else’s words, maintaining that “we are here to be called to, to be called upon, to be summoned into existence.” This tale is not a beginning but a rebeginning, to borrow an expression coined by Laura Riding, who postulates that language is a gift to be given one another, in which and through which we disappear as singulars—like in Kasper’s final vision before vanishing, “a procession […] all of us connected at the wrist by an endless black ribbon.”

It ends with an incantation: Kasper’s swan song, or the mark of his metamorphosis into swan-as-sound that occurs through breath, in and out of language. In another chain of transformations Professor Van Niekerk becomes Kasper, Kasper becomes Xenos, writing as utterance is only possible for them as strangers in a language, when they cannot tread safely and must rely on sense and sound for tentative acts of connection, to reinstate their strangeness that will not allow itself to be erased. Like a magic spell, Kasper’s final words dictated through him by the Swan Whisperer and translated through the professor’s voice alter the common organization of sense, yet can neither be dismissed as nonsensical, marginal, nor pointless. Nor are they meant to lead to a higher understanding: they are very much of this world, because this world needs the awkward and the unpolished, the marginal and the unruly.

“I am still listening. I shall never stop listening. I could not discern the words of his poems, if that’s even what they were.” Such is Van Niekerk’s pronouncement as she listens to Kasper’s tapes in the final part of her account. In a moment of revelation that does not reveal anything but the endless questioning of speech and language, she realizes that “meaning is incidental. What matters are the material words.” And the transmissions that ensue. There is no origin, only an endless reworking, a fabulatory interweaving across the boundaries of language and through languages in the plural. Statements such as “I am the real dummy … and god only knows who is writing in me” testify to the moment when translation becomes transience. She reads Kasper’s words out loud, “in the hope that the water and the plumes will keep whispering them, perhaps whisper them through to him.” The landscape of language is both sensuous and psychological: Kasper’s poems in the tapes were “recorded near to running water or waving grass, […] to provide his voice with a kind of pedal point: not a bold bass pedal as in Bach, but rustling, murmuring, as though time were an instrument played by the transparent fingers of grass and water.” As I read these words I was reminded of the German term Stimmung, a tonality of being that conjoins subject and landscape; of Gerard Manley Hopkins’ inscape; of the Sybil’s leaves bearing their message in a flicker whose meaning exceeds trace or tangibility; of German sound artist Rolf Julius, who “wrote” a concert for a frozen lake, allowing his pared-down poetry and the surrounding landscape to become as much a part of the composition as the sounds; of Adriana Cavarero’s notion of chora, transmitted to her by Plato via Kristeva and expressed in her book For More than One Voice as the extra-linguistic, extra-conceptual quality of voice. I was reminded of Aristotle’s statement, “one must not learn, but suffer an emotion and be in a certain state.” I went back to David Toop’s Haunted Weather and its ruminations around secret sounds and states of becoming; to Emily Dickinson’s “being but an ear” marking the beat of her loss of sense and reason. I dwelled on the implications of my own choice, as a writer, to be a stranger in a second language—its discomforts, its thrills, the meddling with residues from another culture to form other sounds. Finally I recalled sentences by Clarice Lispector’s G.H. urging herself, from the edge of language and silence, to become “far-off landscape”: “Ah, but to reach muteness, what a great effort of voice.”

In only a handful of pages, The Swan Whisperer says a lot more about the ineffable yet material quality of listening, and its complex, necessary relation with cultural residues and language, than do most lengthy tomes. That a thirty-odd page text can disclose all this is extraordinary. That I haven’t yet quite worked out what exactly happens in the end will make for repeated reads that are certain to thicken, excite, and complicate my understanding. I shall say it again: The Swan Whisperer is not a text about writing, but a channel of transmission. It sounds a subtle onomatopoeia of the deep, of murmurs and silences, of the doing and undoing of meaning. Then writing re-begins.

Kasper’s initial struggle to “produce something tangible” is dissolved in the shimmer of his swan song. Read those words: if you try to decipher them you will no longer hear them or see them. Speak them out loud: maybe you will hear Kasper’s voice, Van Niekerk’s, and the Swan Whisperer’s. Maybe you’ll vanish in them too.

Daniela Cascella is a London-based Italian writer. Her work is driven by a longstanding interest in the relationship between listening, reading, writing, translating, recording, and in the contingent conversations, questions, frictions, kinships that these fields generate, host, or complicate. She is the author of F.M.R.L. Footnotes, Mirages, Refrains and Leftovers of Writing Sound and En Abîme: Listening, Reading, Writing. An Archival Fiction, both published by Zer0 Books.

Images by William Kentridge