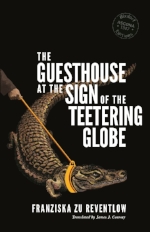

Though largely a conservative society, Wilhelmine Germany was nonetheless home to some of the most progressive and pioneering thinkers of its time. The pronounced militarism and censorship embodied by Kaiser Wilhelm II were counteracted by early human-rights activism and experimental, anti-reactionary art. Yet fiction and non-fiction from this period, in particular from exponents representing the liberal side of these conflicting forces, have remained largely unknown to Anglophone readers. Seeking to rectify this problem, the Berlin-based publisher Rixdorf Editions, in two authoritative translations by James Conway, has now released two texts never before available in English: The Guesthouse at the Sign of the Teetering Globe (1917) by Franziska (Fanny) zu Reventlow, a short story collection; and Berlin’s Third Sex (1904) by Magnus Hirschfeld, which according to Conway is “arguably the first truly serious, sympathetic study of the gay and lesbian experience ever written.”

The Guesthouse at the Sign of the Teetering Globe

by Franziska zu Reventlow

translated by James J. Conway

(Rixdorf Editions 2017)

Reviewed by Tyler Langendorfer

It is hard to imagine a more scandalous and subversive figure in the German Empire than Reventlow, whose individuality and contempt for patriarchal norms (and even those of her feminist contemporaries) earned her the nickname “the bohemian countess.” Born in 1871 to aristocratic parents in Husum (in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein), she received the emotionally reserved upbringing typical of her class in the nineteenth century. Her family’s relocation to the more culturally vibrant city of Lübeck in 1889 offered her a window beyond this confining environment. Here, she had the chance to become acquainted with international literature, such as Tolstoy, Zola, and Ibsen, that challenged the hypocrisies of German social convention, above all the submissive role of women and the centrality of marriage. More passionate about art than literature, Reventlow sought freedom in Schwabing, Munich’s Montmartre and the cultural capital of early twentieth-century Germany. A satirist, free-love advocate, and (less than faithful) translator of French literature, she lived a life marked by debt and illness, unable to obtain financial stability through writing or marriage. Reventlow died in 1918 from injuries sustained in a bicycle accident, too soon for the emergence of Weimar Germany, where, with its more sexually-liberal norms and widespread experimentation in the arts, she likely would have thrived.

Guesthouse at the Sign of the Teetering Globe was published towards the end of World War I, with Germany engulfed in political turmoil and faced with the specter of defeat. Although most of the stories take place abroad, with characters in transit (e.g. on a train, a cruise ship) or on vacation, they nonetheless illustrate this period’s horrific violence, instability (for which the “teetering globe” featured in the title story is an apt metaphor), and tendency toward the grotesque.

Reventlow excels in capturing these era-defining characteristics. Her stories convincingly reflect the tragedy and absurdity of human events, seeming to echo the work of the nineteenth-century German writer Heinrich von Kleist, who stated that “the world is a strange set-up.” Here, in the words of David Luke and Nigel Reeves used to describe Kleist’s writing, Reventlow depicts “human nature” and the world as a “riddle,” where “everything that has seemed straightforward” becomes “ambiguous and baffling.” The influence of the darker side of German Romanticism can also be felt in Reventlow’s use of the uncanny (das Unheimliche in German, meaning literally “unhomely”), an encounter with a strange person, creature, or object that disturbs. It is employed to some degree in the Freudian sense, where the unsettling also attracts. Amplifying the impact of the uncanny is Reventlow’s frequent use of a third-person plural (“we”) narrative voice, a composition of characters that changes from story to story. Conway, in his afterward, notes that “this has an unnerving effect, as it seems to assume a prior knowledge of this ‘we’ (the characters) that we (the readers) cannot possibly possess. We are immediately on the back foot.” All these elements are acutely evident in the title story. A group of vacationers find their plans derailed upon their arrival at a Spanish island, where they are greeted by the eccentric Hieronymous Edelmann. Monocled and sporting a “monstrous” fan-shaped beard, Edelmann tricks the travelers into staying at the eponymous inn, a sinking, “dubious abode” inhabited by idlers “given to alcoholic overindulgence.” Once the vacationers suspect Edelmann of wrong-doing, they attempt to find accommodation elsewhere, only to have their efforts thwarted by (presumably) Edelmann’s menacing reputation. They find upon their return to the inn that Edelmann has enrolled them in the Flame Federation, an international pen-pal network he had recently joined, “which would afford tremendous pleasure to all involved.”

Edelmann (whom the painting The Garden of Earthly Delights by his possible namesake, Hieronymous Bosch, may have inspired Reventlow to endow with an affinity for exotic animals and hedonism) strikes the narrator as a charlatan with a “way of ignoring facts and realities,” from whom normally positive words (fundamental to Romanticism) such as “freedom,” “beauty,” and “pleasure” take on a hidden, sinister meaning. Though he has “given thought to his contribution to the refinement of mankind and its way of life,” his actions (e.g. his enrolling the guests in the Flame Federation without their consent, his attempt to prevent their escape from the island) betray a controlling and megalomaniac personality. Reventlow would die before the rise of fascism and large-scale personality cults throughout Europe, yet as her portrayal of the duplicitous Edelmann—as well as her propensity to base her characters on individuals she knew personally—suggests, perhaps she saw the characteristics of future tyrants in the public figures of her own time. When the narrator refers to the group as “we, the victims of Hieronymous,” her words may not be intended as melodramatic. Rather, perhaps Reventlow is alluding to the prospect of a catastrophic outcome for her country under the influence of such personalities.

“The Polished Little Man,” another of the collection’s stories, could be seen as a variation on this theme, a study of the collective madness and slavish dependency that surrounds such personalities. The story is centered around the tedious existence of five hotel residents in an unnamed “Oriental” town and their obsessive relationship with the “polished little man,” a well-dressed figure with an eerie laugh. The third-person plural narrator states that the “polished little man” is “constantly hopping in and out of our midst” recounting “anecdotes of exotic royalty and persons of high standing in his customary hushed tones.” Although the narrator professes that they can’t stand him, they become increasingly dependent on his presence (“he was absolutely unbearable. Perhaps this was precisely what attracted us”), so much so that their collective will is completely subject to his existence. He has become the master of their fate (“gradually, through no will of our own, he had become the focal point of all our thoughts, determining our lives entirely”) and the only causal agent for the occurrence of events (“or perhaps we had a vague feeling that if anything were to happen at all, that it would only happen through the polished little man”).

This relationship with the uncanny becomes more ominous as the story develops, and a reason for their trance-like state never emerges from these “the ambiguous and baffling” circumstances. One morning, a member of the group, the cavalry captain, returns with minor injuries from a search for a mysterious stranger, a “man with an iron bar” who has injured another member of their circle, and who is suspected of having a connection with the “polished little man.” In the narrator’s eyes, the captain’s injuries “seemed to be an even more sinister outcome than if he had died. Impudent fate was merely toying with us, it never took us seriously.” The arbitrary nature of fate takes on even more mysterious dimension when it is revealed that the “polished little man” seems to go unacknowledged by anyone outside the narrator’s circle, raising the possibility that he is a group hallucination. If true, Reventlow leaves no clues as to the the cause of these bizarre circumstances.

The theme of arbitrary destinies is further explored in “Mister Otterman,” where a scene of happiness is revealed as a mere aberration. At a seaside resort, the beloved of the lawyer Berger inexplicably dies as an unknown stranger introduces himself to her in the water. Suspecting the stranger (who goes by the name Otterman) in his beloved’s death, Berger challenges him to a duel. Berger manages to kill Otterman, but finds no respite in this outcome, as he becomes irrevocably haunted by the latter’s death.

Yet the most disquieting aspect of this story is how both men seem unable to stop this tragedy as it unfolds. Berger, on the one hand, “hardly knew what to feel … had no comprehension of himself, nor of the other man.” Otterman, on the other hand, in a way that seems to anticipate Meursault’s behavior in The Stranger, surrenders himself “blindly and submissively to his fate, a fate he hadn’t made the slightest attempt to avoid since the events of the previous day.” Berger concludes that “why he should have acted this way … would remain forever a mystery.”

Other stories explore different incarnations of the uncanny. In “Spiritualism,” a tale involving a séance with a husband whose murder has gone unsolved, the ordinarily mundane telephone becomes a communication medium for the dead. The spiteful possessions of “The Belligerent Luggage” take on a life of their own, abandoning their owners as they go on a cruise. In “The Silver Bug,” the discovery of a new species of bed bug leads to a romance between strangers.

Though the stories are uneven in quality (one can understand why the underdeveloped “The Elegant Thief” was omitted from the original German edition), Guesthouse at the Sign of the Teetering Globe, with its unconventional plot twists, carnivalesque characters, and existential concerns, will likely appeal to fans of both canonical writers like Kafka and Camus, as well as contemporary authors João Gilberto Noll and Can Xue.

Berlin’s Third Sex

by Magnus Hirschfeld

translated by James J. Conway

(Rixdorf Editions 2017)

While the stories in The Guesthouse at the Sign of the Teetering Globe consist of individuals victimized by the fantastical, seemingly removed from the quotidian, Magnus Hirschfeld’s Berlin’s Third Sex is an anecdotal account of a subject firmly grounded in everyday life: the nature of gay and homosexual relationships in Berlin and the psychological toll of this community’s secretive and marginalized existence. As part of Hans Ostwald’s Grosstadt-Dokumente (a series of fifty-one books dedicated to urban issues running from 1904 to 1908), Berlin’s Third Sex was a political feuilleton written for mass consumption to convince Germans of the biological normalcy of homosexuality and the need for its decriminalization. Hirschfeld (1868-1935), a physician and sexologist based in Berlin’s Charlottenburg district, was a groundbreaking advocate for the rights of sexual minorities. In 1897, he founded the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee, the world’s first LGBT-rights association, and made the repeal of the German penal code’s Paragraph 175, which criminalized homosexuality, a focus of his life’s work. In Berlin’s Third Sex, Hirschfeld attempts to clarify (utilizing most frequently the nineteenth-century term “uranian” to refer to LGBT individuals) that the denial of homosexual rights is harmful to both society and gay individuals, and that the prevention of homosexual behavior, given its scale, is virtually impossible to enforce.

Berlin, which even in 1904 (well before the seemingly gay-friendly Weimar era portrayed in Christopher Isherwood’s Berlin Stories) had a substantial demographic of this minority (50,000, according to Hirschfeld’s estimates), offered bountiful material for Hirschfeld’s text. In his opening paragraphs, he elaborates on the location of his case study:

If one wished to produce a vast portrait of a world-class city like Berlin, penetrating the depths rather than merely dwelling on the surface, one could scarcely ignore the impact of homosexuality, which has fundamentally influenced both the shading of this picture in detail and the character of the whole.

In order to convince his readers that homosexuality should be accepted, Hirschfeld dedicates a significant part of Berlin’s Third Sex to descriptions of homosexual relationships, portraying them as no different from those between heterosexuals. He writes that

Many readers, we can safely assume, would simply never have previously imagined the homosexual to have an emotional, non-sexual life, to have affections and romantic practices essentially indistinguishable from those of the heterosexual.

Most of the relationships in the text take place at social gatherings (e.g. dinners, costume parties, balls) with venues as diverse as mansions, clubs, cabarets, restaurants, and soldiers’ taverns. Hirschfeld covers a broad spectrum of classes and professions, such as students, laborers, prostitutes, military officers, and the aristocracy; the inclusion of the latter two implicating (in Conway’s words) “the very pillars of Prussian propriety.” Most of these accounts were experienced first-hand by the author, who, as a homosexual already well-known for his advocacy work, was often invited to these gatherings.

In spite of Berlin’s relative tolerance towards homosexuality during this period—the city’s chief of criminal police monitored the population but did not rigorously enforce Paragraph 175—homosexuals still had to fear for their reputations. Blackmail was pervasive and ruined many lives. Suicide attempts were all too common, and as Hirschfeld notes “homosexuality” was “not always the direct cause [of suicide], but one” could “almost always establish an indirect link between homosexuality and the violent end.” The author himself counts twenty different individuals within a span of eight years whom he prevented from taking their lives.

Among his most notable calls for sympathy (while adopting, for better or worse, a sentimental tone) are those that concern the loneliness of homosexuals. A passage that addresses the despair felt around Christmas, the “gravest” time of the year, summarizes the full extent of the price they have paid for their sexual orientation. On this day, their thoughts drift “far, far back” to the

time when this day was also a family celebration … many think about their shattered hopes, what they could have achieved if old prejudices had not hindered their progress, and others in respectable positions ponder the heavy lie they must live. Many think about their parents who are dead – or for whom they are dead.

Fortunately, however, not all homosexuals experienced this level of alienation. Perhaps the most moving passages are those that discuss a parent’s acceptance of their son’s orientation. Hirschfeld writes that “in Berlin it is far from unheard of for parents to come to an accommodation with the uranian natures, even the homosexual lives, of their children.” In one case, a gay lawyer leaves the city with his partner and shortly thereafter introduces the latter to his father, a laborer. When the son reveals the nature of their relationship, Hirschfeld writes that “it came as no surprise to the father, who had long suspected something of the sort, and he declared himself in agreement with the situation.”

Hirschfeld’s rhetorical strategy, which includes these appeals to sentiment, walks the line between emphasizing the similarities in behavior between homosexuals and heterosexuals (in other words, suggesting homosexuals are just like the [presumably heterosexual] reader), and relating anecdotes or characteristics that portray the former as uniquely, yet endearingly, different. That this approach has strong parallels with contemporary gay rights rhetoric suggests that there is a timeless appeal in finding reasons for empathy in order to demonstrate that “the other” is just as human.

Berlin’s Third Sex concludes with an entreaty to the reader to consider the current persecution of homosexuals in the same light as that committed against suspected witches in the seventeenth century. Hirschfeld asks that they, “in accordance with the results of scientific research and the personal experience of many thousands of people, … finally see an end to the misjudgment and persecution which humanity will one day look back on as they do the witch trials.” His text may be too sentimental (and perhaps too lacking in scientific evidence) to be thoroughly persuasive, yet it still a social milestone in the scope of its compassion and in the author’s foresight into his society’s capacity, even under authoritarian rule, for social equality.

Reventlow’s work seems prescient as well, and in the case of both authors it is this prescience that makes them feel so modern: The one a Cassandra who seemed to foretell the collapse of Imperial Germany (and perhaps European civilization); the other a visionary who saw a more tolerant and humane future for his compatriots. With the strong focus among Anglophone publishers on Nazi-era and postwar subject matter, it is refreshing to encounter these texts from a period of German history that is no less fascinating. English-language readers can only wonder how much there remains to discover.

Tyler Langendorfer is a New Hampshire-based translator from German and Spanish.

Banner image: Café Bauer, Unter den Linden, ca. 1900. Library of Congress, via Flickr.