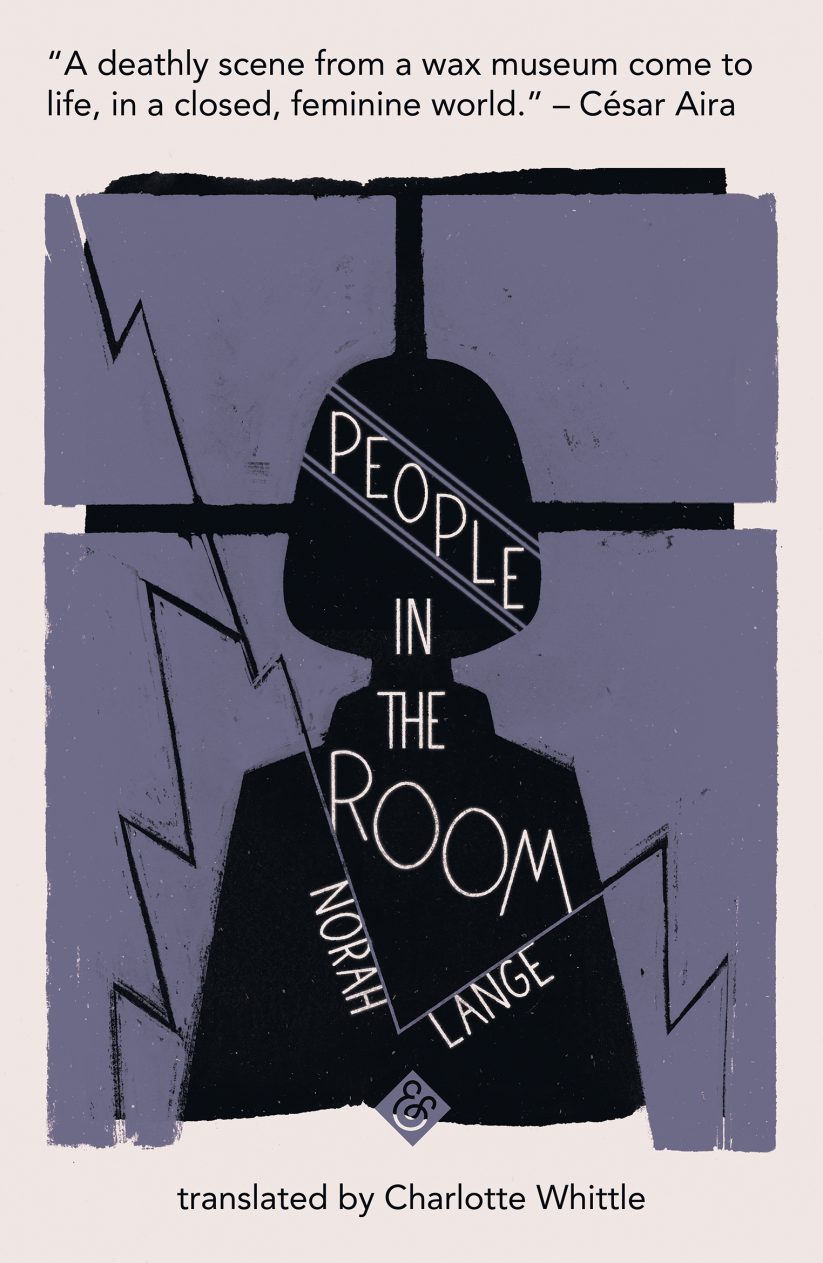

People in the Room

by Norah Lange

trans. Charlotte Whittle

(And Other Stories, Aug. 2018)

Reviewed by Hannah LeClair

In the opening pages of Norah Lange’s People in the Room, a flash of lightning blanches all the corners of a young girl’s bedroom on Calle Juramento, and illuminates the mask-like faces of three women sitting in the living room of the house next door. In that instant, recounts Lange’s unnamed narrator, “I saw them for the first time, began to watch them, and as I watched them, slowly examining their three faces in a row, one barely more elevated than the others, it seemed to me that I held—like the suit of clubs in a game of cards—the pale clover of their faces fanned out in my hand.” Lange’s darkly surreal novel crystallizes around this single moment of transfixion. For Lange’s teenaged narrator, the glimpse of these three women’s mysterious faces is like an “indelible first portrait” or “the beginning of an accidental life story” and her longing to uncover their story becomes an obsession that positions her as the protagonist of a strange narrative. Lange’s narrator enthralls—as she is herself enthralled by the women she watches from her window.

Charlotte Whittle’s accomplished translation of Personas en la sala may be the first chance many Anglophone readers have had to encounter Norah Lange’s writing. For these readers, the author’s biography may be nearly as obscure as the background of this novel’s unnamed protagonist. And Other Stories, the publisher of Whittle’s translation, bills Lange both as a key figure of the Argentine avant-garde and as a writer whose accomplishments have been overshadowed by her role as Borges’s muse. As such, their endeavor to publish her novel in English means that she may now reach a wider audience and take her place in the literary canon alongside luminaries like Virginia Woolf, Clarice Lispector and Marguerite Duras. These names are not arbitrary: Lange came of age in the 1920s, when modernist coteries were the vanguard of the literary scene in Latin America and across the rest of the Western world. As an adolescent, Lange came to writing in the midst of this ferment, because her childhood home on Calle Tronador just outside of Buenos Aires, was a gathering place for a circle of ultraísta poets and writers that included Jorge Luis Borges and his sister Norah (distant cousins of the Lange family), Norah Borges’s husband, Guillermo de Torre, and Oliverio Girondo, whom Norah Lange married in 1933.

The young Lange, who participated in the famous tertulias (salons) of Calle Tronador by declaiming poetry and delivering richly satirical speeches, became a protégée of Borges and began writing poetry of her own. She published her first book, La calle de la tarde (The Street at Dusk), at the age of twenty in 1925, with a foreword by Borges and illustrations by his sister. Following her poetry collection, Lange published an epistolary novel, Voz de la vida (The Voice of Life), and then a more straightforward narrative, 45 días y 30 marineros (45 Days and 30 Sailors), based on her voyage on a cargo ship to Norway. These early novels explore feminine subjectivity and sexuality. In particular, 45 días y 30 marineros lends itself to being read as a metaphorical treatment of Lange’s experience as the only female member of the ultraísta circle, and her negotiation of her role as an objectified girl-muse and an artist in her own right.

In his introduction to People in the Room, César Aira writes of Lange’s early work that “her poetry, while well composed, has the air of an impressive piece of homework . . . The poems are precocious. Precociousness, more than a circumstance, is in fact their very subject matter.” Aira is right to draw attention to Lange’s privileged position: in 1926, Lange, alongside Peruvian writer Magda Portal, was one of only two women included in the seminal Índice de la nueva poesía americana, edited by Borges, Alberto Hidalgo, and Vincente Huidobro. For this group of writers, who coalesced around the experimental magazine Martín Fierro in the mid-twenties, Lange became a modernist muse, lauded as much for her Nordic looks and flaming red hair (she has been described both as a “valkyrie” and as the ultraístas’s “angel and siren”) as she was for her playful spirit and her accomplishments as an author. However, Aira doesn’t quite convey the doubleness of Lange’s position within this male-dominated coterie. For a proper understanding of that perspective, we have to turn to scholarship on Lange and other female writers of Latin American modernism, which, broadly speaking, dedicates a great deal of attention to the ways in which literary women navigated their doubly marginalized position (as Susan Suleiman puts it) with respect to aesthetics and gender within the literary avant-garde: Patricia Nisbet Klingenberg notes that Lange’s image “seems to have frozen her in the midst of her own peers as a precocious child”; Vanessa Fernandez Greene suggests ways in which Lange deliberately cultivated that persona in her life and work; and Vicky Unruh reads across her œuvre to discover the deftness with which Lange moves between the disparate worlds of the literary fraternity, and a more obscure, feminine familial community by “portraying herself as an interloper in both.”

Lange portrays the narrator of People in the Room as a precocious teenager whose acuity of perception makes her feel like an interloper in her own home. We come to know the novel’s narrator-protagonist as someone whose burning desire to tell a story is at odds with her crippling awareness of the limitations posed by her lack of experience, as a sheltered seventeen-year-old surrounded by a happy family. Whose stories and whose secrets does a girl hear age have a right to? In her encounters with the three mysterious women, Lange’s protagonist wants to lash out against them, to declare (as she imagines someone declaring to her, perhaps), “You don’t deserve to keep secrets.” At the same time, part of the reason these women fascinate her so much is that somehow, she says, “deep inside I knew that they alone had the right to speak of death, of ill-timed affairs, of suicides, of bitter loneliness.” Thus, perhaps, it’s all the more agonizing that, when their faces become, for Lange’s narrator, a secret of her own—when they inspire a narrative that begins to unfold with urgency, to alter her, to transform her into the protagonist of her own story—no one notices the drastic ways in which her experience and perceptions are changing.

At dinner with her family, she senses in herself “an urge to argue, to put on airs, to bestow upon the others some of the mystery floating all around me.” She begins to narrate her own performance: “I unfolded my napkin and spread it slowly across my lap, with a sad expression, even though I was happy . . . I felt briefly as if I was dreaming up something dangerous, but for now I wanted to be coy, even if only this once. But no one looked at me as if I was behaving strangely.” Aira suggests that Lange’s narrator-protagonist “occupies the place of a metaphysical Sherlock Holmes operating in a vacuum.” Indeed, what unfolds in People in the Room is a tale of espionage humming with currents of suspense, dread, and desire that crackle with electricity but have nowhere to spend themselves: no crime is brought to light, the mystery is never unraveled, and nothing happens—except for our protagonist’s ineluctable transformation by the persistently obscure presences of the people in the room, and the creation of this very story.

In an interview with Beatriz de Nóbile, Lange revealed that the vision of three women sitting in a living room was inspired by Branwell Brontë’s portrait of his three sisters, which was printed in the newspaper, La Nación. In the painting, Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë’s pale faces gleam in a mask-like trefoil against a gloomy backdrop. The canvas also bears traces of a ghostly presence: Branwell himself, who expunged his own image from the portrait, obscuring it with the light colored and oddly insubstantial-looking columnar shape we now see in the middle of the painting. Branwell’s life story is a tragedy of thwarted ambition: creative and precocious like his sisters, he was the family’s only son and the first of his adult siblings to die—a failed artist who succumbed to alcoholism at thirty-one.

Learning of of Lange’s encounter with the Brontë portrait prompts the reader to seek traces of the Brontës’ influence everywhere in People in the Room: in the novel’s gothic details, its ghostliness, its thunderstorms, and its fascination with tragedy, suicide, and premature death. Lange’s preoccupation with espionage and surveillance recalls Charlotte Brontë’s Villette, in particular. In what is perhaps her most masterful work, Brontë offers her readers a fantasia of espionage and paranoia narrated by a protagonist whose version of events we come to recognize as highly suspect. We are also prompted to recall the fact that all four precocious Brontë siblings fervently inhabited and narrated a make-believe world as children and adolescents: their serious play involved the production of the poetry, plays, epics and periodicals of Gondal, Angria, and Glass Town, realms that they peopled with beautiful ladies, daring heroines and Byronic anti-heroes; prototype Rochesters, Heathcliffes, and Jane Eyres. To the extent that People in the Room is a novel about this portrait, it is fascinating to read the novel as a portrait of play—the dangerous, serious play that might lead a seventeen-year-old girl to become a spy, or a criminal, or a writer.

People in the Room draws upon the tropes of detective fiction, surrealism, and the gothic, but as the story progresses it also becomes increasingly clear that Norah Lange is offering this tale as a parable of sorts about writing and the way it transmutes everyday life into something uncanny—a portrait of the writer as a young girl. Lange’s narrator castigates herself for not having noticed the three women sooner, for somehow having missed the beginning of their story. So, from the very beginning, the telling of her story is framed as a recollection. “Not everything happened at once,” she cautions us, in the story’s opening pages. Lange’s narrator-protagonist’s serious, obsessive play, her narrative-making, reinvests a string of fragmentary episodes with significance they didn’t hold in the moment they were first experienced. The novel’s plotless plot progresses episodically, in a string of provocations. Each of the narrator-protagonist’s tantalizing encounters with the visages of the three women emboldens her to intervene more and more directly in their lives. About a third of the way through the novel, the narrator is moved to insert herself obliquely into the lives of the women she’s been spying on.

On a rainy evening, she waits outside their house so that she can speak to a gentleman caller, whose reception by the sisters in their living room she has been observing through their window, before he gets back in his carriage and departs. Her narration climbs to a high, literary pitch here—her choice to speak and reveal herself to him seems to catalyze a parade of confusingly scrambled somatic impressions and surreal images:

Gradually, his face, sheltered by the carriage hood, his voice, smelling of raincoat, and my favorite tree, suddenly visible as the carriage drew away, revealed themselves to me one by one. Everything was perfect. His voice rising as if from many seats, the driver on his perch, passing just then beneath the streetlamp on the corner, conjuring echoes, perhaps causing someone to lift their gaze, and the people who lived in those houses to think, ‘A carriage is passing…’ though to them it didn’t matter.

Later, she finally plucks up the courage to cross the street. Once she presents herself to the three sisters, speaks with them in their living room, smokes their cigarettes and drinks their pale wine, the stakes are altered. Lange’s narrator has been able to speculate wildly, furnishing the three sisters with guilty pasts and secret sorrows, but now, when she imagines someone posing the simple question, “What are they like?” she freezes. The imperative to put her vision of the three sisters into words seems to menace Lange’s narrator although, privately, she is seized with the urge to record things that they have told her, in their own words.

Her writing takes place at night, as if in secret, and is attended by a welter of intense physical sensations—she writes “with hands like inflated gloves that float,” or tingle as if armies of ants are “marching up and own them.” In the morning, the pages must be hidden away. Finally, the urge to describe the “pale clover” of the sisters’ faces drives the narrator-protagonist away from her view of their living room window and her routine of espionage, and she decides that she must take a trip to spend four days in Adrogué. In the absence of their faces, she finds herself “inventing conversations with people I knew who were incapable of discerning the three faces—impossible to glimpse anywhere but in the drawing room—without assuming, immediately, that I was telling them about a portrait.” Lange’s narrator despairs of being able to explain that the women she has been watching are real people: “It could only be a story about a portrait, a feat for my age, a voyage through their three faces, though I couldn’t even specify the color of their eyes, the way they did their hair, the tentative shape of a smile, as my anger grew and I slipped in and out of sleep.” The torment Lange’s narrator feels as she measures her expressive ability and anticipates the way her story will be received by its intended audience (“a feat for my age”) surely evokes the way in which precocity was Lange’s own torment—and gift.

Notably, and perhaps because of her ambivalence about her role as muse and the tension between her early precocity and serious ambitions, as a mature writer Lange ceased writing poetry and disavowed some of her early work. Aira remarks that her poetry and the humorous speeches she delivered at ultraísta salons (later published in two volumes, Discursos (Speeches) and Estimados congeneres (Dear Assembled Company)), are separated from “the almost mournful seriousness” of her mature prose works by an “enormous distance.” In 1937, Lange gained broad recognition for her prize-winning memoir, Cuadernos de infancia (Notes from Childhood). As a piece of auto-fiction, the book invites comparisons with the work of Nathalie Sarraute and other exponents of the French nouveau roman. It has been translated into French, German, Norwegian, and Portuguese, and the recent publication in Asymptote Journal of excerpts in Maureen Shaughnessy’s English translation highlight it as a work that—in Shaughnessy’s words—communicates “something universal” about the haunting and melancholy particularity of childhood memories. In these excerpts, Norah and her five sisters indulge in morbid reveries (“Sometimes Susana and I would ask each other, ‘What is the most tragic thing?’”) and, together, transform their departure from their beloved childhood home in Mendoza into a voluptuous game of lingering farewells to “familiar trees that we would see no more”: “We kissed the rough bark of a branch . . . sometimes we had to stand on our tiptoes to reach a distant branch.”

The shared reveries contrast, in these vignettes, with other reminiscences that conjure the particularity of somatic experience, as when, Lange recalls

dedicating myself, one very hot afternoon, to discovering procedures that would offer me relief, I found one that produced an immediate and prolonged effect: wiping a cotton ball against a plaster wall . . . The effect was immediate. Shiver after shiver ran up and down my body, the skin on my arms became prickly and a cool tingling sensation shot up my back and lingered on the nape of my neck.

The combination of serious play and attention to the surreality of somatic experience is a hallmark of Lange’s mature work, and it is also a feature of People in the Room. Certainly these modes of seriousness and surreality are in no way mutually exclusive: in Cuadernos de infancia, the two sometimes blend together. Scholar Vicky Unruh points to a passage from the text where Norah recalls how she would “‘nail her eyes’ into a visitor to imagine their profile from within’ . . . as if, she explains, ‘I inserted myself into the person, physically, but only into the face.’” This strange, deeply dislocating game of pretend is something that the Norah Lange who narrates Cuadernos de infancia shares with the narrator-protagonist of People in the Room—a total confusion between the observer and the object of scrutiny; an identification so intense with the people she is watching that it is as if they absorb her or she absorbs them: she puts on someone’s persona as if it were a mask. For instance, the first time the narrator of People in the Room hears the youngest of the three sisters speak, what she hears is this: “My voice, could another voice be mine?” and thinks, “I can’t turn around to find out who’s using my voice, or if I’m someone else, or if I’m not myself and I am mistaken . . .”

Whereas scholars like Unruh and Vanessa Fernandez Greene are more interested in drawing throughlines to connect Lange’s two early novels with her autofiction and later work, Aira points to the publication of her second “autobiographical novel,” Antes que mueran, in 1944, as a turning point in Lange’s artistic development. He characterizes the text as an “unwriting” of her previous memoir: “The authorial gaze is inverted, as if everything were seen from the other side . . . It could be said that the title, Before They Die, sets the tone for everything else that Lange went on to write.” Because People in the Room is narrated in the voice of a mature woman reminiscing about a period of girlhood obsession, the act of reading the novel alongside Aira’s introduction ends up proving his claim about Lange’s trajectory, as well as the trenchant interpretations of Lange’s project advanced by scholars like Unruh. Precocity is a perilous and frustrating state for a young girl to inhabit, and it is easy to see how that tension is also part of what must have motivated Lange’s foray into the unknown and the uncanny.

Indeed, as the narrative develops, Lange draws her reader into realms that become more and more uncanny. People in the Room ends in a surreal climax that unspools across a virtuoustic, paragraph-length sentence. Charlotte Whittle renders its clauses and cadences masterfully, allowing the reader to be drawn more deeply than ever into the whirlpool of imagery, emotion, and somatic confusion conjured by Lange’s protagonist, who envisions

. . .the portraits staring at the wall above the dresser . . . fleeing from all they had listed, not keeping watch on the carriage or the final conversations I didn’t hear, emerging surreptitiously in a wilted clover towards who knows where, after they carried the trunk over their dead father unaware of the belated slit wrists and the discrete wine a spider passed by. . .

The narrator’s vision of the three faces does really seem in danger of flattening, of sinking into two dimensions and turning into portraits instead of people. Whittle’s sensitive translation also communicates the moments in when Lange’s prose torques, when her grammar seems to warp and writhe so that we lose track of the sequence of events, and when the surreality of Lange’s narrator’s language and imagery approaches the poetic.

By immersing us in the protagonist’s frustration with her efforts to bring her vision into words, this novel becomes a masterful realization of Lange’s literary goals. Not content merely to decorate the salons of a male-dominated modernism, Lange discovered that her literary ambitions would require her to invent her own forms and identify her own precursors. People in the Room is a novel in which people are flattened into representations of themselves, portraits take on the heft of indelible characters, and a girl becomes a writer by transforming the limitations of her surroundings into a literary experience—in short, it is a deeply idiosyncratic Künstlerroman. And its ekphrastic origin in Lange’s engagement with the Brontë portrait underscores her preoccupation with a search for artistic antecedents.

No wonder an obscure portrait of three nineteenth-century literary women so fascinated this modernist writer: the sisters’ gazes still look almost feral with an intensity of attention that, as Lange must have recognized, mirrors her own. Lange, who spent so much of her life confronting a male gaze that invited her performance of the role of literary muse, truly came into her own by directing her gaze at muses of her own invention—and witnessing the play of her voracious attention across the pages of People in the Room is precisely what makes this strange, thrilling novel so utterly captivating.

Hannah LeClair is a PhD candidate in Comparative Literature at the University of Pennsylvania.

Banner image: Simulina.