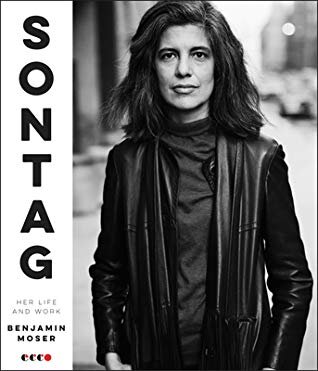

Sontag: Her Life and Work

by Benjamin Moser

(Ecco, Sept. 2019)

Reviewed by Stephen Piccarella

Benjamin Moser’s Sontag: Her Life and Work is the first authorized biography of Susan Sontag, the greatest cultural critic of the twentieth century. The book spans almost a hundred years of cultural and political history, and examines all of Sontag’s published and unpublished work, ranging from fictionalized memoir to academic writing on psychoanalysis to reporting on her experience producing a play in war-torn Bosnia. Moser is a recognized translator and biographer of Clarice Lispector, and to produce this latest work he spent seven years studying a massive archive of Sontag’s papers and interviewing her associates and intimates, some of them family members, others elite publishing luminaries. The book is not as exhaustive as some biographies, but tells the story of a life and of an era with diligence and enthusiasm. Moser’s does what a biography must, and well enough given the outsized reputation of its subject. For a general readership, Sontag is likely to stand alone as an authoritative work.

The circumstances under which this book has appeared, however, include the recent publication of an essay in the Los Angeles Review of Books, by Magdalena Edwards, about her experiences working with Moser on a translation of Lispector, and her subsequent research into his professional practices. The piece details how Moser facilitated a deal for Edwards to publish a translation of Lispector’s novel The Chandelier with New Directions, only to tell her later that her work was unsatisfactory and would require his extensive editing. Edwards was eventually offered a kill fee, and Moser assumed control of her project. Edwards was credited, finally, as co-translator. The piece also recounts numerous instances in which Moser’s professional integrity appears suspect. Evidence has been chronicled that chapter titles of his Lispector biography are lifted from the work of a previous biographer, with whom Moser maintains an uncomfortable relationship. Portions of other writings appear to paraphrase, without attribution, the work of previously established Lispector academics, many of whom do not write in English.

Without serious investigation into Moser’s practices while working on Sontag, evidence of similar wrongdoing is hard to find in its pages. Despite the essay in the LARB, reviews of Sontag are going to be good. Some already are. Moser likely realizes that to pan a book like Sontag takes effort on the critic’s part. If there are specious claims, unfortunate stretches of prose, and needlessly clumsy editorial analyses (there are), they are all part of a moving and overwhelming narrative. For a biographer of questionable talent who employs even more questionable methods, training his focus on such a rich subject is a huge convenience. I was skeptical of Moser while reading his book, and I still cried at the end. It’s sad. She’s brilliant. She’s mean. She dies. There are plenty of reasons to write a literary biography––love for a favorite writer can be consuming, obsessive––but to prove that you can take on the legacy of a formidable subject and succeed is not a good one.

Moser’s book is packed with enough lively moments and juicy details to distract even careful readers from any machinations at work. Torrid affairs with notorious seductresses, expensive nights out with the household names that defined Twentieth Century America, flings with Jasper Johns, Warren Beatty, RFK. Moser offers this last revelation with naked self-satisfaction:

Though Vietnam was in part his brother’s creation, and though he himself was a principal author of the blockade against Cuba, he became a left-wing icon; and though he fathered eleven children, his lovers, on at least one occasion, included Susan Sontag.

This is cocktail party delivery: forget about the politics for a second––wait until you hear this. This sentence is exemplary not just of Moser’s writing style, but of his mission as a biographer. He is there less to honor and more to please, to wow. Anecdotes Moser doesn’t consider essential are cut down to hasty asides to make way for the next shocking twist. Summarizing the life of playwright Irene Fornés, who becomes Sontag’s lover in New York, Moser is so excited to segue into another of these that he barely begins before he digresses:

Irene was dyslexic and had a sixth-grade education. She started working in a textile factory and then began designing textiles herself, which led her to painting. After she met Harriet, at the end of 1953, she followed her back to Paris. There, she began to paint, and back in New York became involved in a ménage à trois with Norman Mailer and Adele Morales, the second of Mailer’s six wives. Adele was renowned for ordering her lingerie from Frederick’s of Hollywood and for being stabbed by her husband—and almost killed—in a brawl.

This paragraph barely provides the information a reader needs in order to follow the plot; the intent here is to build to a punchline. Morales was “renowned” for where she bought her underwear, and, get this: her husband tried to kill her. A lot of people who will choose to read a biography of Susan Sontag already know Norman Mailer stabbed his wife. He talked about it on television. Years after it happened, Gloria Steinem encouraged Mailer to run for office. The public attitude toward the incident has remained astonishingly matter-of-fact for far too long. Moser needn’t––and shouldn’t––bring this up just to gloss over it, but it provides a catchy end to his paragraph.

Beyond courting attention, Moser’s Sontag has an even more dubious agenda. He wants to tell the story of Her Life and Work, but for Moser, the work, the life, is not finished. Much of what Moser reveals about Sontag is difficult to accept without judgment. She brings her school-age son to high society parties and leaves him alone to fall asleep in piles of coats while she networks. She verbally abuses her partner Annie Liebowitz even after accepting millions of dollars of her charity. Although her feelings on the matters are various, complicated, and deeply personal, her refusal to fully commit to either the women’s movement or the gay movement is disappointing at times. Moser takes care not to attack Sontag directly for most of the above. Instead, he spars with her on the level of argument. Particularly in reading her more ethically polemical writings, where he is unable to adopt Sontag’s perspective, Moser aims to revise her thinking to meet his expectations. Discussing some of Sontag’s more polarizing statements and actions, Moser provides essayistic asides that correct or apologize for choices that either history or Moser himself finds regrettable. Constructions like “she had never fully absorbed,” “she had not fully understood,” and “the phrasing may have been unfortunate” become common, and they are hard to miss in a biography of a woman known so widely for absorbing, understanding, and phrasing things well. In some cases, these contextualize comments or positions that might jar or raise eyebrows in this reading climate––no indefensible effort. Moser is not out of line when he questions Sontag’s choice to equate homosexuality with fascism in The Benefactor, for example. In other cases, Moser’s criticism comes off as censorious and even tone deaf, sometimes enough so to embarrass Sontag further along with Moser himself.

Moser’s determination to quibble with Sontag whenever she expresses approval of any radical politic reveals a squareness that verges on ignorance. He does acknowledge that Sontag was one of a number of public intellectuals engaged with the political movements of the counterculture, but cannot read Sontag’s writings of this period in context without arguing against her. As he follows her through the late sixties and early seventies, Moser maintains his skepticism of Sontag’s sincere revolutionary fervor even as she travels to North Vietnam, China, and Sweden in search of utopian communism in practice. He dismisses her interest in the Cuban revolution as a “projection of her own desire to be reinvented.” Sontag’s sympathy with the far left is somewhat performative, but all politics are performed, especially in writing. The political writer performs the certainty she can never achieve in life. When he refuses to allow Sontag to believe, even ephemerally, in communism, what Moser intends as a service to his reader is really a disservice to his subject. At its worst, this kind of reframing extends to obtuse grandstanding that calls the integrity of the book into question.

Sontag’s 1967 essay “What’s Happening In America?” articulates her positions on the cultural upheaval wrought by the Vietnam War. The essay includes a quote for which Sontag still takes heat: “The white race is the cancer of human history.” As far as radical politics go, the quote is not beyond the pale, but the claim and the essay evidently make Moser uncomfortable:

. . . practical politics are missing from “What’s Happening in America.” It was true, for example, that American racism seemed to defy solution. It was also true that less than a year before Sontag wrote this piece, the same president she derided for “scratching his balls in public” signed the Voting Rights Act, a triumphant sequel to his equally monumental Civil Rights Act of 1964. In the century since Lincoln, no leader had achieved anything comparable. But Sontag, who so keenly perceived the intermixture of darkness and light in herself, could not bring such a nuanced reading to her own country.

Moser argues that Sontag lacked the political acumen necessary to acknowledge the Johnson administration’s success toward purging America of racism. This take is as weak as it is bold. American racism runs deeper than “practical politics,” and although Sontag came to regret choosing cancer as her metaphor, she did not regret condemning whiteness. Even after spending years in such intimate conversation with Sontag, Moser can’t manage to see the nuance in her reading. “Hers was not the ‘real’ America,” he insists. “It was America as camp, as aesthetic phenomenon: America as metaphor.” What America is real? Like any soliloquy on America, Sontag’s is rhetoric, not theory to be put into practice. Moser should ask himself: if a reader with his “nuance” were present at a 1967 teach-in against the Vietnam War, in defense of whom would he speak: Susan Sontag or Lyndon Johnson?

Moser begins to speak favorably of Sontag’s politics when she embraces liberalism in the eighties, which tells readers more about Moser than it does about Sontag. When he explains that Sontag’s new friendship with Soviet expat Joseph Brodsky “prepared her for the role she played in the last decade of her life: a voice of the libera—no longer the radical—conscience,” Moser is not afraid to suggest that the liberal rejection of communism is the only sane and ethical choice for an American in the latter half of the twentieth century. “When the Berlin Wall fell,” he later asserts, “even the flintiest cynic might have seen the arc of the moral universe bending toward justice … Communism collapsed, leading to the emergence of liberal governments across a huge swathe of the planet.” Call me a flinty cynic, but I don’t see any real political analysis in this narrative of progress and triumph. Moser may believe Sontag finally publicly states that communism is “Fascism with a human face” in 1982 because she has attained a new political awareness, but I have a feeling the concurrent introduction of neoliberal policy across major world powers might have something to do with it. If revolutionary leftism was the most popular performative mode for fashionable intellectuals in the late sixties, liberalism took its place among those same intellectuals in the eighties and nineties. Endorsing communism at the height of the counterculture was no more campy than preaching liberalism under Reagan. For Moser to advance such a poor reading here in the attempt to redeem Sontag is even more condescending than his earlier suggestion that she might require his redemption in the first place.

Moser delights in delivering the dirty details of Sontag’s personal life for the same reason he attempts to correct her politics: to draw attention to himself. One might expect a writer after this kind of recognition to prefer fiction or poetry, but a biography is a perfect project for a writer with more ambition than good ideas. Susan Sontag was narcissistic herself, and capable at times of manipulations even more objectionable than Moser’s. These Moser catalogues dutifully and with a combination of empathy and angst, as does someone who needs to reconcile the misdeeds of the person he reveres. Sontag was also an exceptional and peerless artist; Moser attempts to improve on Sontag so that he can improve on himself. By inhabiting––with success and to good effect––a figure whose flaws reflect but whose strengths and achievements outpace his own, Moser has managed to place himself at the center of the moving and inspiring story of a literary icon. In many ways, Moser’s biography is a great book. What’s debatable is whether it’s really about Susan Sontag.

Stephen Piccarella is a writer, musician, and community organizer based in Philadelphia. His writing appears in n+1 and The New Inquiry.

Banner image credit: Bob Peterson