Prologue: 1984 – 2008

Southern California, spring, 1984:

The two tenor saxophonists in this high school band could easily be mistaken for members of the basketball team. Seated several chairs apart, they are fairly tall—taller than the average jazz musician, at least—and, more importantly, play with unusual maturity for seventeen-year-olds; in fact, so do all their peers in the California All-Star High School big band, which is currently rehearsing for an upcoming performance at the Monterey Jazz Festival. The saxophonists are named Mark and Donny, and they will soon graduate from Palos Verdes High School and Aptos High School, respectively. In a few months Donny will catch a plane to Boston to attend Berklee College of Music, where he will pursue his dream of becoming a professional saxophonist; Mark will stay in California to attend Cal State Long Beach to study art. Although Mark derives immense pleasure from playing the saxophone, he has other interests: he has always had a sharp eye for design and illustration, and he more recently developed a fondness for break dancing. For Mark, the life of a professional saxophonist does not appear to be in his future.

Boston, winter, late 1980s:

The practice rooms at Berklee College of Music are packed and Chris Cheek, class of ’90, is ready for a break. He sets his saxophone down on the lone chair in this stale, little cubicle and steps into the hall where, peeking out from the churning noise of students practicing, something catches his ear. He follows it several doors down and peers into the window, where a gangly, rail thin saxophonist is diligently practicing a Coltrane solo, the transcription copied by hand. He notices the remarkable tidiness of the penmanship, more like the work of an experienced draftsman than a music school student. The transcription sits alongside pages of what appear to be notes, this particular student’s personal appendix to Coltrane’s musical language. Cheek stands and listens for a few more minutes, then walks back to his cubicle and shuts the door.

Boston, fall, 1998:

Tower Records stands monolithic at the intersection of Newbury Street and Massachusetts Avenue. A glacial procession stretches down the block as eager fans await their shrink-wrapped, midnight-release copies of Prolonging the Magic (Cake, certified platinum September 1999), S’il suffisait d’aimer (Celine Dion, U.S. release, second best-selling French album of all time behind Dion’s D’eux), and other new releases. When one young man finally reaches the front of the line, he causes a minor commotion. “What did you say you wanted a copy of?” A weary employee hastily abandons the stacks of pop, rock, and hip-hop albums at the counter and disappears deep into the store, and several minutes slip by before he resurfaces with the mystery CD.

The next day, the same young man, a Berklee freshman saxophonist from Houston named Walter Smith III, starts picking out melodies by ear from his new acquisition: In This World, Mark Turner’s second release for Warner Brothers. A few hours later, Smith steps out into the hall to clear his ears. He pauses for a moment when he realizes he is still hearing fragments of songs from the album in his head, and then realizes the sounds aren’t in his head; they’re seeping out from practice rooms throughout the entire floor.

Boston, fall, mid-2000s:

At morning rehearsal at the New England Conservatory, the ensemble coach calls a standard, something simple to give the students a chance to blow and get their chops warmed up. The coach counts off the tempo and sits back to let the students take over. When everyone has finished taking a solo and the song comes to a close, the coach looks at the tenor saxophonist. “You know, in this music you’ve got to find your own voice,” he says. He pauses to scan the room, as though to broadcast his teacherly contemplation, before returning his gaze to the saxophonist. “Now, I’m hearing a lot of Mark Turner in the room, but Mark Turner’s not here today. I played with Mark last week. He’s probably in New York somewhere.” The saxophonist looks increasingly uncomfortable. “I didn’t come here to hear Mark. I came here to hear you.”

Brooklyn, fall, 2008:

A few days before his forty-third birthday, Mark Turner is splitting firewood in his house as he regularly does. He favors a power saw. Setting to the work at hand, he is focused and careful, just as he is when he plays the saxophone. This time, however, there is an accident. The rotation of the saw exerts a deep pull, sometimes drawing the wood into the blade with sudden surges. This time, the left hand guiding the wood to the blade is too slow and as the saw takes the wood into it, the left hand is pulled in with the wood.

1. In This World

“I don’t know much about him, to be honest with you; we’re not real close or anything.”

– Chris Cheek, saxophonist

“He’s somebody I can’t say I know that well, and I don’t think anyone knows him that well except maybe his family. I wonder what Ben [Street] would say about him.”

– Ethan Iverson, pianist

“I don’t feel like I know Mark that well—but I don’t say that as a lack, like ‘I wish I knew him better’ or that he’s a man of mystery.”

– Ben Street, bassist

“I personally feel like I’m still just getting to know Mark. He’s got kids and a family and a busy career, so I don’t really get to see him that often.”

– Ben Wendel, saxophonist

“I know a lot of people know him better than I do.”

– Miguel Zenón, saxophonist

* * * * *

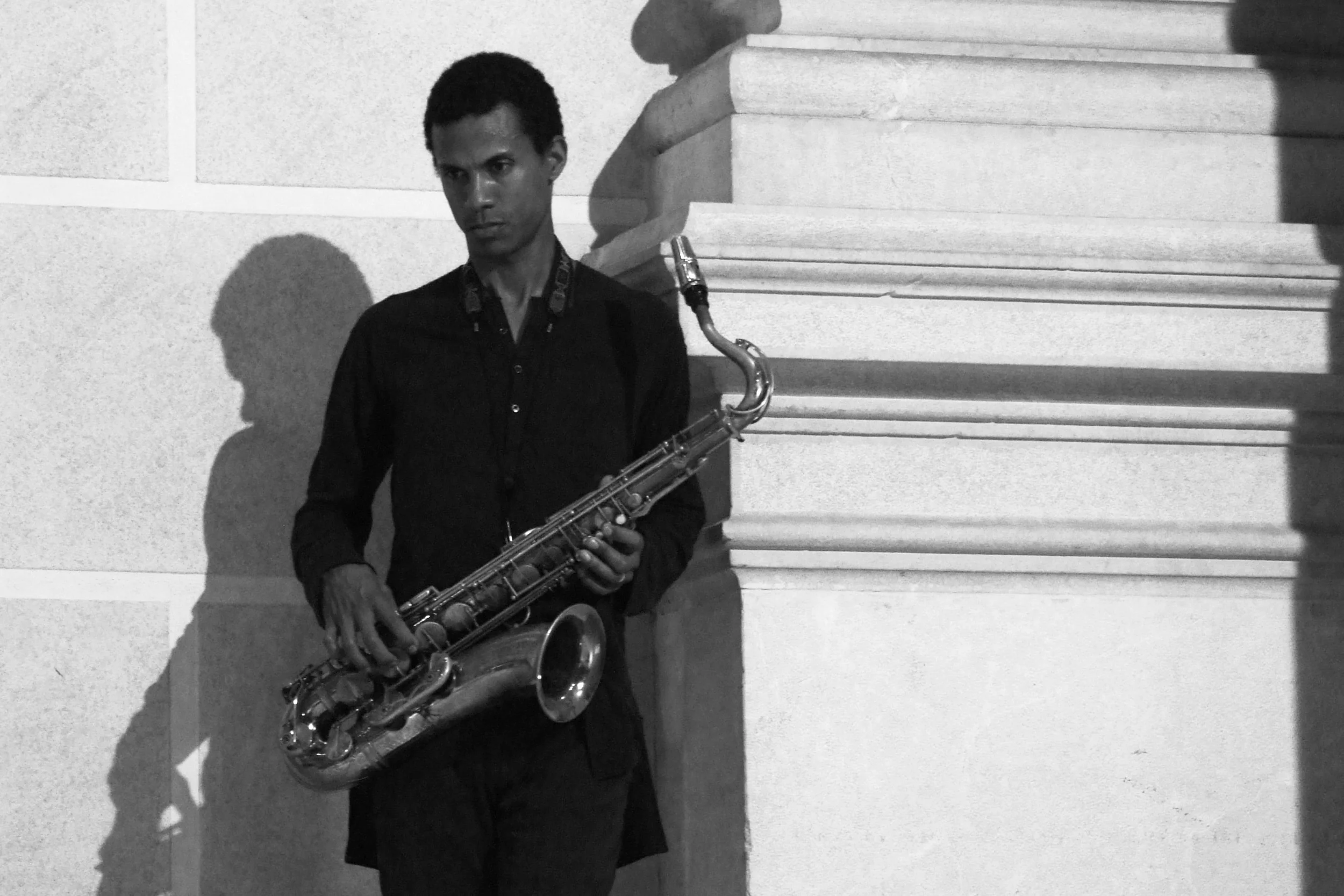

Mark Turner doing the "Mark Turner Leg Spring" (image: Bruno Bollaert, volume12.net)

Go out to hear some jazz and watch the tenor saxophone player. If the player is relatively young—say, under the age of thirty-five—odds are you’ll observe a highly specific body motion: an irregular up-down bend in the knees, feet pointed inward at a shallow angle, giving the impression of a human spring firmly rooted and flexing. There’s no popular name for this, but for the purposes of this article, call it the “Mark Turner Leg Spring.”

The Mark Turner Leg Spring is now so prevalent among saxophonists at jam sessions that non-jazz nerds might mistakenly conclude that the behavior is an essential component of modern jazz saxophone practice. It is not, but it has become one of several predominant traces of tenor saxophonist Mark Turner, who turns fifty this November. Like a ghost, his sound and even his physical mannerisms seem to follow saxophonists everywhere. “It speaks so highly to Mark’s playing,” says Tom Finn, a Brooklyn-based alto saxophonist who studied with Turner from 2010-2011 at New York University, and who is among a younger generation of Turner-influenced saxophonists. “If you can create a cliché, it’s like, you’ve done it, you know?”

As a leader, excluding collaborative and co-led projects, Turner has released only six albums over the past twenty years. Students today often release début albums fresh out of music school, but Turner released his fairly late, at twenty-nine. Although he has recorded widely as a sideman—his Wikipedia page lists about fifty sideman credits—his output as a leader is conspicuously leaner than that of similarly influential peers like tenor saxophonists Joshua Redman and Chris Potter, with fifteen and eighteen albums, respectively.

But the numbers reveal little about an artist whose magnetic sound has burrowed deep in the ears of already several generations of saxophonists now, an infectiously distinctive voice on the horn that has been described variously as “dark,” “dry,” “even from top to bottom,” and “translucent,” and whose melodic inventions and compositions have been called “intellectual,” “harmonically advanced,” and driven by “long, serpentine lines.”

As influential as he is, Turner is also notorious for shunning self-promotion. He was described as “possibly jazz’s premier player” back in 2002, in a New York Times profile suggestively titled, “The Best Jazz Player You’ve Never Heard.” Although elements of his music seem to be everywhere in jazz today, Turner himself remains elusive, resisting the forensics of sonic fingerprinting.

2. Cast in His Image

It’s perhaps a sign of the times that, whereas Charlie Parker’s most extreme followers sought out heroin and other substances in the 1940s and 1950s in the misguided hopes of becoming like their idol, Turner has inspired young followers in matters of healthy living, most conspicuously yoga and vegetarianism, which has not escaped the notice of other musicians.

Toward the end of a recently published interview, trumpeter Nicholas Payton, perhaps best known for popularizing #BAM, or “Black American Music” (a campaign to rebrand and reclaim “jazz,” a moniker which he associates with longstanding commercial and cultural exploitation), commented:

Hey, if you’re really a yoga-loving person and you’re really juicing, if that’s authentically you, that’s fine—like Mark Turner, like that’s who the fuck he is—but a lot of people are posing like Mark Turner or faking it. That’s who Mark authentically is … But other people are afraid to be themselves, and I think that’s reflected in the music.

Every generation has artists who are unavoidable—not so much the elephant in the room, but the elephant parked in the middle of the road, blocking the way.

There was a time in the late 1970s and 1980s when one couldn’t go to jam sessions without encountering sound-clones of Michael Brecker, a virtuosic saxophonist whose blazing, laser focused sound and sheer speed were as widely imitated then as Turner’s style is today. As one anonymous older saxophonist reportedly said of this era, “Michael Brecker ruined the eighth note for a generation of tenor players,” specifically referring to the unmistakably personal way Brecker would phrase the notes in his lines, which often unrolled in a series of individually attacked tones, each decorated with a trademark twang.

Similarly, Turner has dominated the modern jazz saxophone eighth note, contributing to the trend towards eighth notes in jazz becoming straighter—that is, less of the long-short, unstressed-stressed delivery and more of an even unfurling—according to tenor saxophonist Ben Wendel, who first heard Turner’s music as a student at Eastman School of Music in the late 1990s. (He spoke on this same topic for a 2011 Times article.)

Handwritten lead sheet for Turner's "Zurich," recorded on his debut album, Yam Yam

As with past giants of Black American improvised music, Turner’s influence is not just limited to his instrument. The vocabulary he has developed on the tenor saxophone has slowly trickled into the common language, a process expedited by musicians with the persistence to adapt his innovations to their own, very different instruments.

Trumpeter Jason Palmer, a 2007 graduate of the New England Conservatory, has long been a fixture on the Boston jazz scene, having maintained a weekend residency with his band for over a decade at Wally’s Café Jazz Club, Boston’s longest continuously running jazz venue. Before landing that gig, Palmer worked for several years during the early-aughts as an orderly at a rehabilitation center in East Boston. He often worked the overnight shift, which gave him an opportunity to listen to Turner’s albums on repeat and gradually transcribe the jagged, modernist compositions, ultimately deciphering some of their sophisticated logic.

“The one thing I really gathered from this was that he rarely repeated himself verbatim … execution-wise it’s very difficult,” he says, emphasizing the leaping, angular nature of Turner’s saxophone lines that are less natural to the trumpet.

While Turner has served as a model for melodic invention across instrumental families, he also serves as a model of how to negotiate the tricky business of finding a personal sound through studying and, at times, imitating admired elders and ancestors.

“He has no reservations completely getting absorbed within a player, like really going all the way in and reading about their history and really trying to—‘imitate’ is kind of the wrong word—but really embody the spirit of that player,” Wendel says. “But he also feels strongly that everybody can’t help but sound like themselves at a certain point, so he doesn’t have any fear of getting swallowed up himself, losing himself.”

Melissa Aldana, a 2009 Berklee graduate, won the Thelonious Monk International Jazz Saxophone Competition—the biggest in jazz—in 2014, but prior to that she had devoted years to exploring the sounds of other players, most notably Turner’s.

“I was just into Mark for many years. I didn’t check anything else out,” she says. “It got to a point where I was like, ‘Okay, I have enough and probably will damage myself to keep imitating him,’ so I just let it go and things just start[ed] coming out, things I learned years before, and everything started making sense.”

Walter Smith III & Ben Wendel (image: Dave Robaire)

And before Aldana there was tenor saxophonist Walter Smith III, who graduated from Berklee in 2003. Smith has already spawned his own bevy of high-school-aged imitators, but back in high school and college, he was still digesting the styles of numerous saxophonists, including Charlie Parker, John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, and Sam Rivers. Entering college his modern tenor saxophone heroes were Joshua Redman and Branford Marsalis. Then he discovered Turner.

“It got pretty obsessive,” he says. He was not alone. “I’d definitely say that for anyone under forty, maybe even above, it’s kind of like the sound. At this point, you can almost tell how old someone is by if they sound like Trane, they’re over forty; if they sound like Mark, they’re under forty.”

But at a certain point, he felt it had gone too far.

“I used to go in the Berklee practice rooms and sit there for hours and learn little things of Mark’s and perfect them,” says Smith, “but then I had to stop because I realized that it wasn’t just me—it was everybody that was doing it. I would go out in the hallway and everyone was working on the same stuff, so intentionally at the time I had to be like, ‘Okay, I have to find something else that’s not so popular right now.’”

There are no shortcuts to identifying and nurturing the components of a personal sound. Aping the surface elements of a distinctive player can be a stopgap measure to cast the illusion of personal style, but that only lasts as long as others can’t identify the source. “I heard a lot of players who I thought were super-original, until I heard Mark,’ says Finn, “and then I was like, ‘Okay, that’s where everything is coming from.’”

3. Family Tree

“Other people learn more by osmosis or just by actively playing. I definitely need to learn every single tree in the forest and put them all together over time—a very long, long time—in order to play.”

– Mark Turner, Interview with New York University’s Steinhardt School (April 2015)

The mythology of jazz, especially as it pertains to influence and perceived artistic lineage, is often a fishy combination of anecdotal evidence and simplification for the sake of convenience. As alto saxophonist Myron Walden, a 1994 graduate of the Manhattan School of Music, points out, tracing influence in jazz has long been a dismal science resistant to neat, linear narratives and discrete episodes of cause-and-effect. “When you understand influence—how it has the ability to infuse with who you are or you with it and become it—you would know that I’m not just going to mimic or be influenced by one artist,” he says. “In the beginning, you might focus on one guy to try to understand what he’s doing, but in developing a style or in embracing music, you open up to the plethora, because everyone has something.”

The prevailing narrative surrounding the genesis of Turner’s now-instantly recognizable sound is that he began in college much like his peers, emulating and learning to reproduce with exacting detail the nuances in phrasing and articulation that distinguished the masters of his chosen instrument: John Coltrane from Joe Henderson, Joe Henderson from Wayne Shorter, Wayne Shorter from Sonny Rollins. The turning point, as the story goes, came shortly after college, when Turner discovered Warne Marsh, a relatively obscure white tenor saxophonist who weaved sinuous lines with a lighter, almost feathery sound that was a far cry from the rougher, gruffer sound favored by most of his black contemporaries. (Marsh’s influence on Turner has been given extensive critical attention elsewhere, notably in a 2008 master’s thesis by Jimmy Emerzian written at Turner’s first college, Cal State Long Beach.)

Marsh was associated with the blind Italian-American pianist Lennie Tristano, a fierce pedagogue often described as a cult leader-type figure with idiosyncratic theories of improvisation involving the creative subconscious. A priority held by Tristano and his disciples was to avoid repeating oneself verbatim by practicing spontaneous creation. They didn’t practice lines and figures to play on the gig; they practiced playing lines and figures they hadn’t practiced before, on the spot. In other words, they practiced how to really improvise. (Asserting any notion of “true improvisation” pops a can of contested theoretical worms, however, which is far outside the scope of this article, but has been in the crosshairs of critical improvisation theory in recent years.)

Marsh provided an appealing alternative to the mainstream, so Turner, fusing Marsh’s throaty, warbling tone and Tristano’s improvisational methods with the harmonic innovations of Coltrane in the laboratory of his ear and mind, discovered a winning formula that, in time, became a style of saxophone playing that had never been heard before. That’s how one telling of the story goes, at least.

But, as many saxophonists have found, developing an original sound isn’t as simple as hitting on obscure influences and grafting them onto pre-existing molds.

“People started telling me, ‘Oh, he’s just playing Warne Marsh stuff. Check it out if you don’t know it,’” Smith says. “I checked that out and I was like, ‘Well, maybe, but this is something a little bit different here.’”

Ethan Iverson & Mark Turner (image: Jeff Tamarkin)

Pianist Ethan Iverson is perhaps best known for his work with The Bad Plus, the collaboratively led prog rock-meets-jazz trio, but he has played with Turner since the 1990s in numerous configurations, most notably in legendary drummer Billy Hart’s quartet since the mid-2000s. He also suggests that there’s more to Turner’s sound than the conventional narrative allows.

“The Warne Marsh stuff sticks out because it was so unusual at the time, but I think at the end of the day it’s a little bit of a miscue in terms of what he actually is up to,” says Iverson. “In terms of the way he plays, what he’s aspiring to and personalizing is John Coltrane’s spirituality.”

Many musicians interviewed for this essay referenced Turner’s practice of Buddhism, and several commented on potential connections between Turner’s spirituality and his musical personality. For example, Wendel wonders if there’s a connection between creative meditation on a single idea and the role of Buddhism in Turner’s life, “a deep exploration in a small kind of way,” as he puts it. Wendel offered a secondhand account of Turner describing his own learning style to someone as the opposite of the “forest before the trees.”

“He has to see every leaf on the tree before he sees the tree. Some people, they see the big picture really fast, whereas for him it’s about the microscopic and the detail, and expanding out,” Wendel says. “He’ll explore, let’s say, some triadic or chord formation, all the hundreds of possible variations of that throughout the horn in a really detailed way, and then move on.” It’s this thoroughness in his practice, Wendel says, the expansion of the small to the large, which lends such unusual gravity to Turner’s note choices. One pitch somehow reveals previously invisible designs like a ray of sunlight cast upon a silvery spiderweb.“When he’ll play a single note and the note sits in an unexpected place within the chord—and maybe ‘not quite in the chord’—it has this weight to it where it’s almost as though you can hear all the implied tonality underneath and around that note, because he’s explored that,” he says. “It’s like he’s hearing that note in a really different way. It’s not random.”

In addition to Turner’s note choices, his orientation as a soloist with the rhythm section is worth considering, according to Iverson.

“They have something that’s coming up from underneath the music, and it sort of sits in the rhythm section right alongside it,” Iverson says, comparing Turner to Henderson, another influential tenor saxophonist and composer born about a decade after Coltrane.

Saxophonists and horn players in general often get bad reputations for steamrolling rhythm sections, eagerly spilling licks they’ve rehearsed in the practice room on the pianist, guitarist, bassist, and drummer serving as collective placemat. Turner, Iverson says, is no such saxophonist.

“It’s this other kind of invitation to the dance, which I believe is an essential thing to Joe Henderson. He’s really inside the band, and Mark is like that, too.”

But that’s not to undervalue Coltrane’s persisting influence. Iverson adds:

The problem with modern jazz playing a lot of times is that it just lacks that vulnerability. Coltrane, for as much shit as he played, always had that vulnerability, and that’s what really inspires us all, [including] all the non-musicians who love Coltrane. Everybody understands when a Coltrane record comes on, some of that feeling and that sound, loneliness and vulnerability—even when he’s burning the house down. That’s the thing that we all tend to miss in our modern jazz burn these days, but Mark has that.

Iverson was not the only musician interviewed who compared Turner to Coltrane.

“When we listen to someone like Coltrane, for example, we, as musicians, hear things very differently than a regular person would,” says alto saxophonist Miguel Zenón, a 1998 Berklee alumnus and long-time colleague of Turner’s in bands such as the San Francisco Jazz Collective. “A regular person might hear a certain energy or a certain spiritual thing, but we hear hard work. We hear practice. When I hear Mark, it’s kind of the same: I can tell that this guy spent a lot of time practicing and working this stuff out.”

Billy Hart (image: Bruno Bollaert, volume12.net)

Billy Hart, a master drummer who got his start on the D.C. scene in the 1960s, has worked with seemingly everyone—Herbie Hancock, Stan Getz, McCoy Tyner, you name it—but just missed the chance to play with Coltrane, who out of the blue one day called Hart on the phone, inviting him to play. At the time, Hart passed because he simply felt he wasn’t ready, but not too long after that phone conversation, Coltrane passed away, from liver cancer.

Having had Turner in his band for nearly a decade and having observed the steady rise of the saxophonist’s star among critics and musicians alike, Hart takes the comparison to Coltrane a step further.

“Mark’s very lyrical, and that’s one of the things that moves me. A lot of students now can get around their instruments, but I don’t hear the lyricism. Now, you think about something like if I had to replace Mark,” he says. “Of course, I had to deal with some possibilities, but there was nobody I could say, ‘Okay’ [snaps fingers]. Nobody. So then, for the first time, I had to think about it like when Miles had to replace Coltrane.”

Demand for Turner continues to rise, but supply remains inflexible as imitations and substitutes abound. Turner has indeed become irreplaceable in Hart’s band as in other bands. This may be partly for the reason Walden suggests, that Turner studied not just a few great saxophonists but embraced the multitude; however, saxophone ancestry is only a part of the puzzle. Turner’s centered yet elastic playing says as much about who he studied as it does about the community of peers he came up with and the scene that he dove into headfirst as a young man: New York City in the 1990s...

The second and concluding part of this essay is available here.

Kevin Sun is a Boston-based saxophonist, composer, and author of the blog A Horizontal Search. He is a member of Great On Paper, a postmodern jazz collective that will release its début album within the next six months, and has been a longtime contributor to Jazz Speaks, the official blog of NYC's The Jazz Gallery.

Banner image: Simone Capretti; manuscript fragment (from Turner solo on "You Know I Care," by Duke Pearson): Stephen Byth