Introductory note: Part One depicted scenes from tenor saxophonist Mark Turner’s life between 1984 and 2008 and surveyed his impact on younger saxophonists as well as the older players who influenced him as a young man. Musicians introduced in Part One who reappear in Part Two include: drummer Billy Hart, pianist Ethan Iverson, alto saxophonist Tom Finn (New School, ’10), alto saxophonist Myron Walden (Manhattan School of Music, ’94), and tenor saxophonist Ben Wendel (Eastman School of Music, ’99).

4. They Were All Monsters

“It took some people off guard, like, ‘You can’t be that studious or that cool,’ you know? ‘How come he’s not shrieking? How come he’s not playing this cliché or that cliché?’”

– Ben Street, bassist

When Myron Walden visited Turner’s apartment in Brooklyn for the first time in the 1990s, his ears registered astonishment.

“I couldn’t believe the amount of saxophone I was hearing in one room at that time,” Walden says, recalling that Turner shared the apartment with drummer Jorge Rossy, who appeared on Turner’s first album, and tenor saxophonist Joshua Redman.

In those years Walden played regularly with bassist Omer Avital’s band at Smalls Jazz Club, a West Village basement club that has been open since 1993 (save for a period between 2003 to 2006) and has long been a major venue and popular spot for late night hangs and jam sessions. Avital’s band at one time featured Walden as the lone alto alongside a trio of tenors that often included Turner, plus bass and drums.

“There was a rotating cast of tenor players, and, whoever they were, they were all monsters,” he says, noting their deeply shared camaraderie, which he believes was more prevalent then than now among saxophonists. “We talked saxophone, we talked reeds, we talked mouthpieces, we would say, ‘What are you practicing, or what are you working on? Oh, man, it sounded like you were working on this.’ Or, ‘Oh, man, that’s really coming together, I hear it evolving.’”

Considering how the myth of the lone practicing musician has persisted over the years—Charlie Parker practicing eight hours a day in a woodshed out in the Ozark Mountains, or John Coltrane practicing day and night, before and after the gig, and even during the break between sets—it isn’t hard to see why Turner would be lumped into this perceived lineage. In numerous interviews, articles, and liner notes, an overwhelmingly popular descriptor is “studious,” with an implication of solitary discovery, but all of this practice took place in the shadow of an immediate, everyday necessity: going out and playing with others.

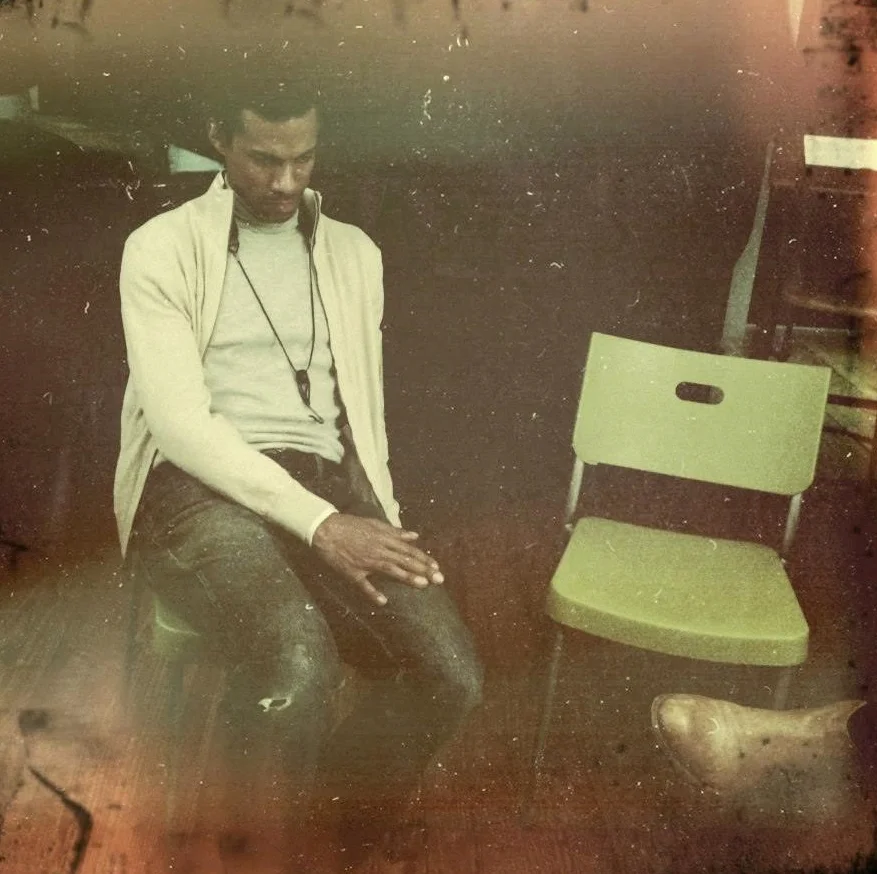

Myron Walden (image: Helen Chang)

In particular, Walden suggests that playing in bands with multiple saxophone soloists, such as Avital’s band, served as an invaluable crucible for personal style. Outplaying one another wasn’t the point; the point was sticking to your guns, resisting the temptation to shred for the sake of shredding, and presenting your truest self in the wake of an epic solo.

“When the saxophone player takes a solo, and he burns the house down, and the leader calls you next—it’s like, ‘What now?’” he says, his voice building with intensity. “He just burned the house down! The stage is still smoldering, and now you have to step up to the plate. That is the test, and we had to deal with that multiple times within a night.”

Imagine following Mark Turner, he says, or any of the great saxophonists who shared the bandstand at the time, which may have included other young virtuosos such as Greg Tardy and Charles Owens. “You have to have the fortitude to stand up and say, ‘This is who I am,’” Walden says. “That’s not easy when ‘the pressure’s on.’”

What’s more, there was little precedent at the time for Turner’s Tristano-influenced cool, his deliberate moderation of instrumental histrionics while playing for audiences conditioned to expect a firestorm every time. In this regard, the burden of the saxophone lineage was perhaps even heavier for Turner, who bore the stamp of a then-unpopular, underrepresented sound, than for peers more easily identified with the surface aspects of popular saxophonists such as Michael Brecker and John Coltrane.

In retrospect, Turner’s commitment to the understated sound approach taken by Warne Marsh and other Lennie Tristano-associated saxophonists steered mainstream reception favorably toward those artists. “I didn’t know a note of that when I was younger. I just thought it was like the bad, unseen white guys from the era where the much hipper shit was all the black cats out burning,” Iverson says. “Mark’s interest in it almost sort of validated it … for him to be like, ‘No, these guys are really happening’—that was a signpost not just for me, but for all sorts of people. I’m sure of it.” (Iverson has written on Tristano and company extensively on his blog.)

In addition to the challenge of resisting the saxophone trends of the time, there also was the simple matter of the instrument having seemingly been explored to its outer limits. It isn’t as though saxophonists in the 1990s felt there was nothing left to do, but expanding upon the monumental technical progress made by previous generations would mean first catching up to Brecker, Coltrane, and other innovators.

Tenor saxophonist Chris Cheek, who graduated with Turner from Berklee in 1990, recalls the awe in which his peers held their immediate forebears, including Joe Lovano, born thirteen years before Turner, in 1952, and Brecker, born three years before Lovano. “Mark has really pushed the boundaries of the instrument, I think, and it would be hard to say how that started,” he says. “We heard Joe Lovano playing a lot of high notes and different sounds and textures, and that kind of expanded our awareness of what was possible.”

Donny McCaslin (image: Nadja von Massow)

“Talking about altissimo, Michael Brecker was the guy who all of us to certain degrees were influenced by; he was completely dealing with the instrument,” says Donny McCaslin, a 1988 Berklee graduate and friend of Turner’s since high school. “I think we grew up where, ‘Well, that’s something that you gotta do,’ where you really have the instrument at your disposal.” (Turner has long admired Brecker, defending his legacy against detractors after his premature passing at the age of 57. As Turner said backstage to Iverson in a rare moment of verbal passion at the Village Vanguard, “Fuck those motherfuckers who don't give it up for Michael Brecker.”)

As McCaslin indicates, among the more conspicuous traces of this lineage is the now-common use of the altissimo register, very roughly the saxophone equivalent to falsetto. (Saxophonists will testify, however, that consistently and accurately sounding one’s first altissimo note will likely take months longer than squeezing out a falsetto note.) The altissimo has been a feature of saxophone playing since the early 20th century, but how it has been exploited and, in recent years, naturalized in the modern jazz saxophone vernacular is a major part of the story of Turner and his generation.

Whereas searing high note cries à la Coltrane became standard practice for the Brecker generation, the altissimo of Turner’s generation, which includes peers such as tenor saxophonists Seamus Blake, Cheek, McCaslin, Potter, and Redman, among others, bears a signal difference. Rather than primarily working up to sustained high notes as a climax within a solo, they phrase entire melodies and complex lines in the highest register, effortlessly executing phrases that saxophonists generations before would have found demanding even in the mid-range.

“As a saxophone player, one of the things that jumps out is just his range, the way he plays the altissimo,” says Zenón. “Even when I heard him the first time, that jump[ed] out, because it’s not usual—maybe now it is, but then it wasn’t.”

In the drop-by-drop technical evolution of instrumental virtuosity, hearing is believing: “His [Turner’s] ability to construct such intricate lines that crossed multiple octaves with ease … I don’t know if I’ll ever get to that level of fluency,” says Walden, “but it’s always in the back of my mind that it’s possible. I heard it.”

5. Labyrinths

Beyond his technical prowess and distinctive sound, Turner also seemed to be at the right place at the right time when, soon after moving to New York, he was invited to join guitarist Kurt Rosenwinkel’s quartet, which featured Turner, bassist Ben Street, and drummer Jeff Ballard. At the time, they were all relatively unknown, but before long they were “jazz famous,” as music school students like to say.

“It seemed utterly new,” says Iverson, who would later play in the Rosenwinkel band alongside Turner, “and that was a really crucial band for a lot of us.”

Among other identifying characteristics, Rosenwinkel and Turner favored pungent harmonic schemes with precisely mapped dissonances, and many of the compositional and textural aspects of their music have been widely imitated. Turner ultimately recorded four albums with the band, which offered many their first enduring impression of his playing. The band’s music emerged at a crucial time where young improvisers struggled to reconcile their eclectic tastes to their love of classic jazz records.

Kurt Rosenwinkel (image: Anders Chan-Tidemann)

“It seemed like you either played very free and acted like you didn’t care so much about the tradition—you were irreverent—or you totally worshipped the masters and tried to sound exactly like them, and we [Street and Ballard] didn’t sort of fit in either one,” says Street of early-1990s New York. “We wanted to play free, but we were listening to Blue Note records as well as to reggae and Stevie Wonder—which now sounds very feigned and cool and mature, but at the time it didn’t feel that way. It felt fucked up.”

Rosenwinkel’s band synthesized their diverse musical influences into a language arguably as recognizable today as bebop. Still, describing this music without getting into theoretical arcana remains a challenge: Iverson identifies a “sort of advanced polychordal or modal sort of language that’s the base of that sound,” while pianist Edward Simon, who has recorded with Turner on numerous occasions, including on Turner’s eponymous début for Warner Brothers, describes the music in an email as “chordal and intervallic, veering on the edge of atonality.”

Turner himself offers a vivid description of his early compositions in the liner notes to his first album, Yam Yam (1995):

I’m not thinking about painting, but that’s a very accurate way of looking at the tunes … They’re basically melodies played off of melodies. Harmony isn’t necessarily functional. It’s more like whatever color is needed. There are common tones, and the forms are odd on purpose.

As harmonically sophisticated as Turner and Rosenwinkel’s music is, jazz harmony has had no shortage of restless explorers in the decades since Coltrane’s passing. In the case of Turner, his influence on improvisers may have as much to do with his nimble traversal of these harmonic labyrinths as the mazelike architectures themselves.

“Mark has this way of threading these complex chord structures so that it’s authentic to the changes, but at the same time seems really improvised, in the way that a Warne Marsh solo is really improvised,” Iverson says, observing that musicians prior to Turner, when faced with harmonically complex forms, tended either to play “pretty much on the grid”—that is, stuck to spelling out difficult harmonies for fear of losing their way—or else to quickly abandon the harmony in favor of rhapsodizing and free association. Both were effective methods, but they had become conventional, even safe.

Just as Rosenwinkel’s band proved through their music that there was no either-or between traditional styles and modern tastes, Turner showed that even the gnarliest harmonic terrain could yield beautiful melodies.

“Usually there’s some kind of inverse relationship between how many notes you’re playing and how fast you’re playing them, and how melodic or how well-considered each one is, because you have limited time and limited melodic imagination,” says pianist Aaron Goldberg, who has played with Turner in numerous bands over the years, including Rosenwinkel’s quartet in the aughts. “What made him unusual was his ability to weave very long lines that were provocatively interesting to a sophisticated ear, yet [to] have them always be in a very tight relationship to the changes as they were going by. He always had that and he still has that.”

Kurt Rosenwinkel & Mark Turner (image: Per Kreuger)

Charlie Parker’s solos, heard slowed-down, reveal their melodic essence and logical patterning, which might sail over casual listeners’ heads at tempo. Similarly, Turner somehow defies the strictures of time by spontaneously composing melodies whose elegance and detail are commensurate to the harmonic landscapes surrounding them.

“He took it a step further, taking the lines you’d hear Warne or Tristano play [where] it almost sounds like they’re thought out and pre-played,” says alto saxophonist Alex LoRe, a 2009 graduate of the New England Conservatory of Music who, like Finn, is among the youngest post-Turner generation of improvisers. “But when you practice a certain way, you learn to develop these lines off the cuff.”

With the right collaborators and years of experimentation both on the bandstand and in the practice room, Turner slowly but surely connected the dots, one note at a time, so that others could follow his lead.

6. A Spiritual Discipline

As of this writing, the third most-viewed Mark Turner video on YouTube, behind “Kurt Rosenwinkel – ‘Zhivago’” (+398K views) and “Kurt Rosenwinkel Group – ‘Jacky’s Place’ [2006]” (+130K views), is entitled “Mark Turner warming up!!!,” with over 50,000 views since being uploaded in November 2006. Providing a complement to Finn’s quip about the significance of creating clichés, one user commented four years ago: “You know you’ve made it when a video of you *warming up* has over 33 thousand [sic] views.”

Many young musicians study Turner’s note choices with semi-religious fervor, but it’s hard to say how many study his attitude toward the notes. Turner and many of his close musical associates seem to share at least a general orientation toward their chosen profession, which is understood as somehow more than just a job or even a passion.

“I’m not sure how he feels about it, but I feel there’s a certain family duty with this music,” says Street. “I really want to join what people have been building on—and not just make some new thing for the sake of my show-biz ego or something like that. I think we’re just fascinated by how this all started how many thousands of years ago.”

Turner, whose own voice has been largely absent from this piece until now, has been interviewed more and more frequently in recent years. In this short YouTube clip advertising his latest release, Lathe of Heaven, he speaks candidly about his continually developing relationship to the blues and the African-American roots of jazz:

For the last five years or so, I’ve just been trying to figure out: what is the blues and what does that mean to me? You know, you’re in school, you’re a jazz musician, you should deal with blues and swing, but I think it needs to be personal and meaningful and have some kind of reference that you can touch and hold and do something about—because otherwise I think the blues can be banal. And I’ve heard it, I hate to say, done in that way all too often, and I actually believe the blues to be sacred, like a spiritual discipline, and it needs to be taken seriously [emphasis added]. So I’ve in a way avoided it because I felt I would disrespect it.

Turner’s profound awareness of this heritage has been an abiding feature of his work since the beginning of his recorded career; to wit, the title of his first album, Yam Yam, comes from the nickname of his maternal grandfather, Lewis A. Jackson, whom Turner described in an interview as his “greatest influence,” period, and the liner notes end with a three-paragraph dedication to Jackson. (Turner’s second album, his eponymous début on Warner Brothers, similarly includes a dedication to his paternal grandfather Harrison Brown and leads off with none other than “Mr. Brown.”)

Lathe of Heaven

by Mark Turner

Mark Turner (tsax), Avishai Cohen (tpt), Joe Martin (bass), Marcus Gilmore (drums)

(ECM, September 2014)

Although Turner is sometimes perceived as cool and even aloof, he is anything but casual as it pertains to approaching music, where the sacrifices of his forebears demand that it be respected and treated, in his words, “like a spiritual discipline.” It goes without saying that talk is cheap, but according to musicians interviewed for this piece, the weight of Turner’s words are reflected in the forceful centeredness of his sound and, perhaps more importantly, with the thoughtfulness that, by many accounts, governs his life.

“Mark is a highly disciplined individual who lives an exemplary life,” Simon writes. “It is reflected in every aspect of his vice-free life. He is studious, dedicated (practices saxophone daily), exercises regularly (yoga and running), he maintains a strict vegetarian diet and on top of all this he is a caring family man.”

Just about everybody interviewed for this story took a moment to testify to Turner’s work ethic as well as his overall ethic as a family man and human being. In particular, both Hart and alto saxophonist Ben van Gelder, approximately equidistant generationally above and below Turner, respectively, mentioned being struck by his bringing one of his children on tour with them.

“Can you imagine that? Imagine yourself bringing a child,” says Hart. “Just think about bringing a child on the road and practic[ing] and get[ting] enough rest to focus and play music on the gig. He’s deep, man.”

7. Seeing the Forest

Mark Turner & Ben Street

Following an accident in 2008 involving firewood and a power saw, which severed tendons and nerves in several fingers of his left hand, Turner was back to performing in just a couple months. In the years since, he has never sounded better. Much of this seemingly miraculous resilience might be attributed to sheer discipline and willpower, but several musicians also noted other personal qualities that might explain such sustained intensity and growth over the years.

Although Turner is known for his thorough, detail-oriented preparation, he just as importantly maintains a longer view toward his time and his world. According to Iverson, not every solo Turner plays is a home run, but he doesn’t mind; his focus is on the much bigger game.

“He’s really unafraid to fail,” Iverson says. “Career shit, making the tune work—none of that matters; he just sees it as an epic cycle, and that’s why he’s Mark Turner. That’s why he gets to these great heights, because he has this other kind of warrior in him for whom failure is just another pleasant way to pass the time, you know?”

Saxophone playing, just like anything else, has its fads, but Turner seems stylistically to have planted his feet firmly and pointing slightly inward since he moved to New York.

“Just being around someone like [Mark], it puts a lot of things in perspective and makes you think about who you want to be … what you’re willing to sacrifice for your music,” says alto saxophonist and 2000 Berklee graduate Jaleel Shaw. “Regardless of what’s happening on the scene, Mark stays Mark.”

As Turner himself points out in the NYU interview cited previously in Part One, deciding what to practice is not just a day-to-day affair, but part of a lifelong commitment toward realizing an artistic self. “A lot of that in particular is just gradually clarifying your aesthetic and trying to figure out what you need to do to reach that aesthetic,” he says. “Otherwise, you can be practicing for millennia! I mean, you can practice one or two things for hours and hours and hours, twenty-four hours a day until you die. You have to decide on something.”

Avishai Cohen, Joe Martin, Mark Turner, & Marcus Gilmore (image: John Rogers/ECM Records)

Turner has already made some of the most widely disseminated and admired music of his generation, and now, with a new quartet featuring both peers (trumpeter Avishai Cohen and bassist Joe Martin) and younger cohorts (drummer Marcus Gilmore), he continues at an unhurried but seemingly unstoppable pace toward whatever he is searching for.

“I didn’t feel entitled at all to become a musician. I still don’t,” he says in the same interview. “It’s still kind of an adventure, like I’m still trying to keep it going. I’m glad it’s still going. It could end at any moment. It could be done next year.”

That being said, Turner seems poised to carry on as he has for the past few decades, although many hope that he won’t wait so long to release his next album. (Thirteen years elapsed between his final release for Warner Brothers, in 2001, and his return as a leader in 2014. He has cited focusing on raising his children as a major reason for the wait.)

“He’s like the D’Angelo of jazz, in a way,” says Shaw, referring to the far-from-prolific but massively influential neo-soul tunesmith while laughing at the comparison—one that may not be wholly without merit, considering their colossal statures in their respective streams of African-American music.

Although many questions surrounding Turner remain unanswered and are perhaps unanswerable, one longstanding question did elicit a concrete answer: namely, the rationale behind the Mark Turner Leg Spring. Wendel, who asked Turner directly about this, explains that there is, as one would expect from him, a calmly considered logic to the unmistakable posture:

I had a feeling—and I was kind of close—that part of the reason why he turns one foot in was something about aligning the hips, because when you’re playing the sax the right hand is down so there’s always a little bit of correction that needs to happen. He basically does it a little different now where his left foot is in further ahead than his right foot and he feels that his legs are like springs on a car. He’s able to kind of balance and float his body weight differently by doing that. It’s really a physical consideration and he’s really thinking about alignment and body motion.

And now that I tried it, it’s like, "Yep, that makes a lot of sense."

Epilogue: Scenes In The Life of Mark Turner, Intimated and Imagined (with a Coda)

Mark Turner walks into the hotel lobby with his bandmates. As they queue up to check-in, Turner splits from the pack. He walks around the lobby and the surrounding room, and he does not neglect the gaudy bouquet at the literature display stand in the corner. He selects one pamphlet among the many trifold brochures and studies the reading material. Only after he has satisfactorily examined the brochure and replaced it to its original spot among the tiered wire pockets does he return to complete his check-in.

*

Mark Turner takes a seat at the table of an undistinguished but fairly clean South Indian restaurant. This place has been recommended to him several times by bandmates, and he has long enjoyed good, spicy Indian food. He politely converses until everyone is served, and when his plate is finally before him, he begins to make an almost imperceptible humming sound, an indication that he is immensely pleased.

*

In the customs line at the airport, Mark Turner stands beside his bandmates. They have had a long flight and are looking forward to performing before the enthusiastic European audiences whose loyalty has made touring possible year after year—but first they have to get out of customs and get some rest at the hotel. He pulls out a slim paperback from his bag, zips it closed, and calmly reads as he waits to reach the front of the line.

*

As usual, Mark Turner has prepared and studied the music diligently before the first rehearsal, but the bandleader has brought in a fresh composition to read. Scanning the information before him, he begins to sound the notes to himself so that he has a sense of the compositional form. He plays the melody, then begins to play the bass part as well to hear the relation between top and bottom voices, and then begins to add a third voice between the melody and the bass to hear the quality of the chords as they move from one to another. This process does not take long, and by the time the group begins to play the piece together, it sounds uncannily as though he has been playing this music for a long, long time.

*

During a private lesson, a student is working on fluency with long lines of eighth notes. The student recently attended a masterclass led by pianist Barry Harris, an octogenarian master of bebop, the language of Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell, and their contemporaries. As he plays, the student remembers Harris’s first words: “I bet if I went around the room and asked you to play, I wouldn’t hear a triplet out of any of you.” The triplet is a bebop trademark: three notes crammed into the space of one, lending motion and density to the eighth note line. At one point, Mark Turner stops the student and offers some advice: “Sometimes, I like to break a long line of eighth notes by playing a quarter note.”

* * * * *

(Coda) Boston, fall, mid-2000s:

Mark Turner isn’t in the room, as the ensemble coach has just made clear: he’s out in New York or Connecticut or somewhere, far away and anywhere but this rehearsal space at the New England Conservatory. “Don’t play Mark; play you,” the coach implores. “Play you!” He starts counting off the same tune once more and signals to the saxophonist: try again. The saxophonist squeezes his eyes shut and, against the sonic gravity of so many hours of transcription and imitation, begins to uncouple himself from the stylistic references buried deep in his ear.

Without calibrating to the sound of one of his heroes, he feels imbalanced at first, but before long something strange happens. In his mind’s eye, he is staring blankly into an enormous bullseye: no matter where he throws the notes now, they always land true and fair, right where he wants. When he finally opens his eyes, he isn’t sure how long it has been since his bandmates ceased playing behind him, but he also realizes now that he can’t see them: the palm of a hand is within an inch of his face, eerily still.

Finally, the hand closes the gap and presses gently against his forehead. “You’re finding it,” the ensemble coach says, lifting his palm. A holy quiet descends upon the room. “Class dismissed.”

Kevin Sun is a Boston-based saxophonist, composer, and author of the blog A Horizontal Search. He is a member of Great On Paper, a postmodern jazz collective that will release its début album within the next six months, and has been a longtime contributor to Jazz Speaks, the official blog of NYC's The Jazz Gallery.

Banner image: Pat Kepic; manuscript fragment (from Turner solo on "You Know I Care," by Duke Pearson): Stephen Byth