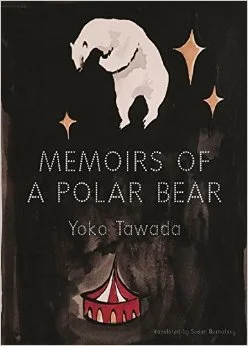

Memoirs of a Polar Bear

by Yoko Tawada

tr. Susan Bernofsky

(New Directions, Nov. 2016)

Review by Alexandra Primiani

Where else would a confused and slightly paranoid polar bear find good inspiration but in Kafka’s stories? When the first of the three protagonists of Yoko Tawada’s Memoirs of a Polar Bear is introduced to Kafka’s “A Report to an Academy” and “Josephine the Singer,” readers unprepared for Tawada’s playfulness and sense of humor might be forgiven for thinking the scene a bit on the nose. Her capable hands, however, have brought us a novel equal parts brilliant and strange, hysterical and disturbing. Tawada’s fifth novel to be translated into English is divided into three sections, which tell the stories, respectively, of a nameless grandmother polar bear, of her daughter Tosca, and of her grandchild Knut. Each is attempting to write their stories down—we do get snippets of both the grandmother’s and Tosca’s prose—and what Tawada exposes is language’s strangeness, to the degree that it seems only natural to be learning it all from a polar bear. Each story reveals layers upon layers of miscommunication, languages piled upon one another. This aspect alone underscores the extraordinary work Susan Bernofsky has done in bringing Tawada’s nuanced style into English.

Translation is so often an act of making an opaque text transparent for a new cadre of readers, but the real magic of Bernofsky’s work has been to maintain the nebulousness that Tawada granted her protagonists in the original German. The three narrators in Memoirs of a Polar Bear go through distinct experiences that expose language as a faulty and inefficient tool when it comes to relating to others. As one of the characters in the novel observes, “the thoughts of animals were written clearly on their faces as if spelled out with an alphabet.” The problem really seems to be when these polar bears are forced to make sense of their lives to their human counterparts. Whereas the nameless grandmother must physically travel from East Germany to West Berlin, and then Canada to reclaim her own narrative (a translation from Russian to German would, she fears, inject another culture’s specific politics into her very personal story), her daughter Tosca is given voice in the usurped dreams of her trainer, Barbara. This regression continues to a strange extreme, as the last member of this lineage of memoirist polar bears, Knut, is born completely without a sense of self, and only finds it through a manner of imprinting, wherein he studies the human caretakers around him, and the zoo at large. The title itself alludes to the more singular trajectory of the story: Memoirs of a Polar Bear collects these experiences so as to offer insight into our inability at understanding individuals around us.

Perhaps this disorientation is endemic to Tawada’s prose. As she was born in Tokyo and moved to Germany when she was twenty-two, Tawada has written in both her native language of Japanese, and German, and in one specific work, Where Europe Begins, experimented with writing in both language simultaneously. While we English-speaking readers have of course read Tawada in just one language, her earlier oscillation between two languages offers a reinforcement of this particular narrative. Tawada focuses on “the outsider,” and with this doubling of language gives weight to their own reality. But while a multiplicity in language helps the reader understand the protagonist’s position, these characters themselves oftentimes must find refuge in other realities. Like in her previous novel, The Naked Eye, the protagonist Anh is pushed to the outer limits of their world by their inability to communicate. She instead finds solace in the simple pleasures afforded to them by the senses: Anh’s world becomes defined by the films of Catherine Deneuve. Tawada deals heavily in the ideas of alienation and otherness, and as such there’s genuine comfort to be found in her clear and energetic exploration of all the senses. Memoirs of a Polar Bear insistently proves that sight, touch and taste—the senses—are truer than language and verbal communication.

Each of the three chapters in Memoirs of a Polar Bear begins with a momentary disorientation: we are not sure who is speaking, but somehow we can trust that what is being represented is real, especially because the descriptions depend so entirely on creating a strong visual, or a decent display of action through the senses and not on verbal communication (i.e., language).

In the opening scenes within each of the three sections, Tawada zeroes in on the characters’ sensory origins to illustrate their basic identities before society has a chance to distort them.

In the first chapter, the nameless grandmother is “tickled,” she is “curled up, becoming a full moon, and rolled on the floor.” It continues with Barbara, who explains her body’s reactions to Tosca when they are alone onstage, the audience invisible to them both. “My spine stretches tall, my chest broadens, I tuck my chin slightly and stand before the living wall of ice, unafraid. It isn’t a battle. And in truth this ice wall is really just warm snowy fur.” Finally, we are introduced to Knut in the third chapter: “He turned his head away, but the nipple came with it as if glued to this mouth. There was a seductive sweet odor, his brain could melt in it.” Touch, sight, taste, and smell. Before their stories are told, before they are confused or misconstrued by language, we are given these moments of their reality. The rest of each chapter diverge to tell their distinct stories and struggles with language.

The anthropomorphized, nameless polar bear of the book’s first section finds herself intrigued by the writing process. This narrative is set deep within the twentieth-century Soviet Union, a monolith unaware of its impending collapse. She confides her interest in a former acquaintance, a sea lion who discreetly and without her knowledge publishes her story in installments. When the polar bear discovers her work is being translated into German outside of the Soviet Union, she fears her voice will be robbed of its story. Taking things into her own hands, she travels to West Germany and learns German. The multiple linguistic levels of this episode are a wonderfully inventive way for Tawada to explicitly convey the dangers of trusting in just one language: “I hoped it won’t confuse me to be suddenly writing my life in several languages at the same time,” the polar bear says to herself. “Something that can disappear is called ‘I’.” The narrator questions the authenticity of her own story as she is learning this new language. No longer trusting that she can convey her past in this new language, she decides instead to write her future from here on out. She believes it much easier, then, to define herself anew and to build her identity within the confines of this new language. And so this polar bear takes on the successive, sometimes overlapping identities of Exile, West German, Canadian, and finally—as she gives birth to Tosca—mother.

Out of this birth comes the next section, which centers on the life of Tosca. She is at first without a voice, without language, until she meets Barbara, a wild-animal tamer at an East German circus. The trainer learns of Tosca’s talents, studies her history in Canada, Europe, and Russia, and invites her to join her troupe. Although Tosca’s story is told obliquely, from Barbara’s perspective, both Tosca and Barbara’s lives are shown in high relief. In her dreams, Barbara begins to speak to Tosca and with each passing night, they become closer. As the two start to get to know one another, a transference occurs. Tawada’s humor helps propel an otherwise disturbing and disorienting story:

“First you should translate your own story into written characters. Then your soul will be tidy enough to make room for a bear.”

“Are you planning to come inside me?”

“Yes.”

“I’m scared.”

We laughed with one voice.

Barbara initially promises to write Tosca’s story, but tells more about her life each day. It took many years and much heartbreak for Barbara to be accepted into the circus, a lifelong dream of hers. Upon joining, however, reminders of her non-circus pedigree can be found everywhere. A colleague warns her of the inherent differences between circus people and city people, “a normal citizen can’t really survive in the circus. A lion can’t become a tiger.”

Simultaneously, Barbara is working with the circus to design a spectacular performance with Tosca and the other polar bears donated to them by the Soviet Union. As they approach a new and inventive way of displaying Tosca’s talents, Barbara’s identity retreats. The division between Barbara’s world, primarily made up of language and human interaction, and Tosca’s insular and animal world breaks down. Barbara fully loses her footing in the human world just as they begin to tour their performance known as “The Kiss of Death.”

In the time since our first kiss, her human soul had passed bit by bit into my bear body. A human soul turned out to be less romantic than I’d imagined. It was made up primarily of languages—not just ordinary, comprehensible languages, but also many broken shards of language, the shadows of languages, and images that couldn’t turn into words.

Perhaps it is because of Barbara’s identity as an outsider to the circus community that she yearns for this connection with Tosca. Mixed in her head is the language of the circus and the language of the city (her childhood), two separate identities she has struggled to combine. With Tosca aiding her, she no longer needs to be a part of either identity, but a distinct, wholly unique one.

The years Barbara spends touring with Tosca are told primarily by Tosca herself. As if this performative kiss nightly cemented both of them to this role of “other,” they lose all connections to the cities and otherwise human world they inhabited off-stage. “We remained isolated from all . . . the circus was an island.”

This apparent solitude sets the stage for the true solitude of the book’s final section, which takes place in the present day, and draws on a story that actually happened. In the early 2000s, the Berlin Zoo became one of the first to nurture a polar bear cub to adulthood. The real Knut was an international sensation whose presence coalesced certain societal issues. In both real life and the novel, the mother Tosca refuses to take care of her cub. In the novel, Knut’s section begins with an omniscient narrator detailing the bear’s day-to-day interactions with his caregivers. At first, Knut is confined to his immediate surroundings: a cage where he spends his nights and the larger research lab with his caregiver, Matthias. As Knut grows, Matthias takes him on early morning walks throughout the zoo, introducing other animals to him and giving structure to the world he previously had only heard or seen through the windows of the lab. “Every outside world had yet another world outside that filled me once more with unease. What was outside the zoo? And when would I finally be able to reach the outermost outside world?” Knut, sadly, cannot imagine how there might be no end to the layers of “outside worlds” for him; with each new exploration offered him by his human caregivers, he will only recognize his otherness even more, and grapple with his identity in relation to all those worlds.

On one of these particular walks, Knut encounters a sun bear, who mocks the young polar bear for referring to himself in the third person. Even as Knut feels angered and duped by language (“Knut was Knut. Why shouldn’t Knut say Knut?”), so do Tawada’s readers feel hoodwinked as they realize the section has been narrated this whole time not by a presumed neutral narrator but by Knut himself. In the real-world version of this story, Knut was more than a polar bear to his devotees: he was the symbol for animal rights activists, of global warming concerns, and of the role of zoos in larger society. So it is fitting that Tawada plays with his identification, and proves the inherent fragility of such arbitrarily imposed significance and symbolism.

After his encounter with the sun bear, Knut focuses his attention on imitating his caregivers, even as this act engenders a new confusion. “And what did Matthias call himself? ‘I.’ What was even stranger was that Christian too referred to himself as ‘I.’ Why didn’t they get confused if they all kept using the same name?” This act is reminiscent of Knut’s own grandmother, who in the first section also questioned the truth behind a word such as “I.” Knut’s purpose within the zoo had never been self-actualization, but simply to be a model for the progress of zoos. In this context, the pronoun “I” serves no function for him.

Tawada’s latest novel continues her dialogue with alienation. While these are heavy and disorienting topics, Tawada’s playful humor keeps readers fully engaged in the characters struggles. Kafka, too used surrealist wit and enigmatic language to explore the inefficacy of self-identification—and it is Memoirs of a Polar Bear that proves how essential Tawada’s voice is in the contemporary literary world. Like Josephine and the ape, Tawada’s three polar bears beautifully relate humanity’s inability to truly connect. Exile, estrangement, confinement: all Tawada’s characters metamorphose under these constraints and are forced to reestablish their identities in new means. It’s through our perception of language—and perhaps our misguided assumption languages plays in our lives—that Tawada fantastically explores those moments.

Alexandra Primiani is a freelance book reviewer and works in publishing. She is originally from Miami, Florida.