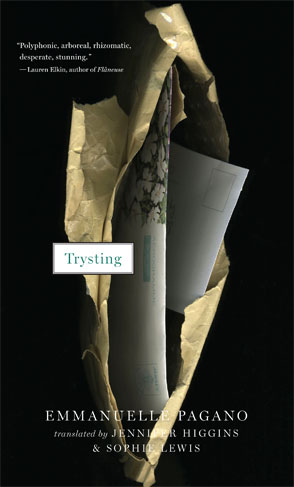

Trysting

by Emmanuelle Pagano

tr. Jennifer Higgins & Sophie Lewis

(And Other Stories & Two Lines Press, Oct. 2016)

Reviewed by Lauren Goldenberg

Language fails as a means to define love; the sentiment is too great, too felt to be held in words. The French author Emmanuelle Pagano’s first book to be translated into English, Trysting, manages to convey the emotion indirectly, definition via fiction. The simplicity of its English title belies the strangeness of the original French, Nouons-nous. Reviewing the various definitions for nouer and trysting, some current, some obsolete, some very specific (the final of six definitions for “tryst” in the Oxford English Dictionary is: An appointed gathering for buying and selling; a market or fair, esp. for cattle) it became clear that Pagano’s achievement is contained within the combined definitions of the two titles. To tryst means to meet at a designated place and time (surprisingly, the OED gives no mention of love or lover). Nouer is a bit more complicated, but en bref it means to tie up, to knot, and the reflexive form means to establish, engage, take shape, begin. Roughly, I read nouons-nous as something like knotting ourselves. Pagano’s book is a series of episodes, whether a brief glance or many years, that reveal the myriad ways love occurs. As two people are brought together, there’s a connection, a start, a moment’s knot. Some of the passages underscore one particular aspect of a relationship and are only as brief as a sentence, while others, running a couple of pages, bring together a wider array of themes. There are no names, often no genders, no ages. Just two people, crossing paths.

Above all the book bears the stamp of emotional truth; there exists no single way to capture or experience love or its loss. There is sweetness, intimacy, humor, pain, loss, suffering, violence, ephemeral unique things that only occur because two particular people intersect at a specific moment in time. The moment of love is a tryst, the formation of a knot.

To read through the slim volume, is to find all your own memories of different relationships coming to mind—ones that you’ve experienced, ones that you’ve witnessed, ones that you could imagine coming to pass. This resonance speaks to how universal many of the trysts actually are; a fair number, for example, center around sharing a bed. Even as the feelings Pagano’s characters experience in this space—intimacy, thrill, boredom, tedium, violence—verge on the particular, they are familiar; to be awake while your bedfellow sleeps unaware of you is so common as to be almost mundane. “I watch him sleeping and feel very far away during these long nights of insomnia. I gaze at him, so calm, wrapped up in the bedding. I’m completely alone next to this sleeping man.” The bed is the closest space to share with a partner, yet even here loneliness exists, and insensitivities can speak magnitudes. “I can’t stand it anymore, this being dragged awake at night that he puts me through, when I’ve fallen into a deep sleep and he comes to bed after me, loud and lumbering, not bothering to check if I’m already asleep.” In the multiplicity of these scenes, Trysting seems to insist love is created, made, and lost in bed.

The bedtime passages demonstrate in part one of the central themes running through the book—those things that we feel and notice about our partner but refuse to say out loud, those sentiments that Pagano shares only with the reader and that we share with no one at all in our own lives. “With him I always felt pleasure without showing it. I wouldn’t fake it—on the contrary—I’d hide my orgasms from him.” Another episode fixates on the dishonesties in a relationship, raising that question of how well we can ever know the person we are with: “So I lie to her. I need her in order to become the man I must become, but I’m not sure I love her . . . I would like her to teach me not to lie anymore, but if I stop lying, I’ll no longer be able to tell her I love her.” Even when an occasional one-liner reads as a platitude that can almost go without saying because so many people have had this same thought, its underlying truth shows precisely why Pagano included it. “No one sees what I see when I look at her.” Not even you, reader.

There is the way love appears to the outside world, the way that same love exists for the beloved, and the way that love exists only within the lover’s thoughts. As it appears to the outside world, there is a passage towards the end of the book that is abrupt and pointed, “I wonder if, when they hear the banging that seems to be coming from our apartment, our neighbors think he’s doing some renovations, even late at night, or if they hear me too, whimpering and begging him to stop.” Pagano at once brings us into this darkest part of the intimacy in this couple and at the same time shines a light on the rest of the world, and the reader wonders along with the narrator, do the neighbors really think nothing is wrong or is this a willful blind eye? Another take on love in the public’s eye that comes a little later:

He isn’t very relaxed in groups, and at the slightest hint of emotion, he stutters. He stutters saying my name, and I love it. I think he’s noticed, so he does it a lot, calls out to me, says my name. When we’re alone he never stutters, but as soon as we’re out in public, having a drink with friends, he turns to me on the slightest pretext, multiplying my name in his mouth.

Other passages encompass an entire life and touch on several themes, several truths. A few I read without thinking twice, some made me chuckle with their frank humor and others shocked me in their uncanny similarity to my own experience. I laughed out loud at a particular few that brought back immediate memories and feelings of adolescent angst (the fraught nerves of speaking to your crush on the phone!). At the same time, Pagano’s sections on age and aging, at once connected to and distinct from the theme of time’s passage, are subtly moving. One of the stories that struck me the most is the following:

In the beginning, as a timid newcomer, I allowed myself to fall into the arms he held out to me. I had only moved into the retirement home under pressure from my children. I felt lost and betrayed. He was there, he comforted me, he offered me the solace of a love story at an age when I thought I had forgotten everything about love. When I found my bearings, he left. I’d forgotten nothing about love; it hurts as much as ever. He moved on to a resident who is starting to show signs of dementia and has trouble remembering things. One of the nurses told me to stop crying. She said it wasn’t worth it. She has known him for years, and he only latches on to women who are disoriented. He wants them to need him. When they recover a bit, like you, he leaves them. It shows you’re doing better.

The narrator’s age has not changed her feelings: “I’d forgotten nothing about love; it hurts as much as ever.” Age collapses love here—at first it might be joyful, but the familiarity is that of pain. I also noted that the language of the elderly narrator’s conversation with the nurse is resonant of many I’ve had with friends in our twenties and thirties. Is the truism of plus ça change one to fear or to accept?

This passage is a cousin to one about a person in an intensive care unit after some kind of accident. The nurse here ignores all requests to call the patient’s wife and instead takes the patient’s hand: “The young woman’s hand wasn’t helping me or calming me down . . . The hand held mine without hurting me and without comforting me.” The whole passage runs maybe half a page, and we are in a confused fog, the patient’s own pain causing us ever more worry, until its final lines hit: “And suddenly that hand drew away and was replaced by a different one. This hand was rough and wrinkled. I squeezed it hard. It was old, twisted by years of work, by life, all this life of ours.” The passage is recast; we are relieved from what we’ve just read, allowed to see the power in a gesture, the restorative strength offered by the love of a life that has been fully lived together.

Many passages highlight sweetness, joy, and the other positive facets of love. But a thread of loss, heartbreak and difficult recovery runs through. And while Trysting may be about how to love, Pagano is also examining how to live. Life lived tied to other people, life lived when that comes undone. One speaker’s life comes apart when his girlfriend leaves him: “My basic functions were abandoning me, just as she had; I didn’t have the strength to cry, or even enough water in me for tears. When tears, hunger, thirst, and digestion returned, I realized that I was alive and that living, filling my belly, getting things moving, getting dirty, would help me forget her.” It seems obvious but the experience of love’s arrival and departure is quite literally lived through, there’s no way but through. In another episode, the speaker has an indescribable oppression that is “just a little too persistent. I have to live with it, since I don’t live with him anymore.”

Love can be cruel and tortuous; misleading in that it promises the most but will also leave you and cause you the deepest suffering. Sometimes even while it is present:

Our bodies, our house, our things, everything had to be beautiful. Otherwise, he would say, we can’t go on. He found me fat, dowdy, and brash, brash in how I dressed and the way I spoke. I was ugly and tacky. Because I loved him, I lost fifteen kilos, let him choose my clothes, and above all, I took to living in silence, afraid that with my noise, my everyday noise, the noise of my life, I would annoy him. He thought I was vulgar in spite of everything. I would have liked to shout, to really test the limits of our bodies and our voices; I would have liked to shout, play, take pleasure. I thought that’s what living was about.

Notwithstanding the impossibility of such an act, Trysting attempts to translate emotion into words, and Jennifer Higgins and Sophie Lewis have reenacted this endeavor by translating these words from Pagano’s language to ours. Translation, fittingly, is directly addressed by a translator in love with the writer whose work she translates:

I’ll never dare tell him how I feel . . . And yet I am en tête-à-tête with him almost constantly, when I’m working on his books. I’m in his head, in his language, in his sentences. One day I bumped into his wife, we even had a chat, and I realized that she doesn’t know him as well as I do, I who spend my time probing his most intimate thoughts and examining his every word as I translate his books into French.

To translate a feeling to a written expression and make an emotion literal, physical, to give it form—this is what Pagano succeeds in doing, giving shape to the inexpressible, the fleeting thing felt but never said out loud. Her book is remarkable in its refusal to be limited to the revelatory or the shocking or the surprising. Some of the fragments wander a little—they don’t go off course in terms of theme or subject matter, but they lean to the fantastical, or fable-like, and these feel a step out of place. I didn’t love the final passage of a woman observing a man drawing a tree who attracts all manner of songbird, but it did bring me back to the beginning of the book, the sounds that you hear with someone: “I wake up, and I can hear the sound of little creatures walking around on an invisible cloth stretched tight next to my ear, stretched between me and him.”

I cannot pretend I did not finish working on this review until after the election. And, after the death of Leonard Cohen—news that I received on a bus to Boston, and that brought me to tears. Feeling broken of spirit and of heart, this book review suddenly felt silly. But, as I found various constructive avenues for my nervous energy, I kept thinking about this slim volume—what it means to write and read about love between people, in all its forms, in a time of its glaring absence. I have no great conclusion to offer, but have noted every single act of kindness between strangers over the past days, which are not unlike these trysts—brief, but poignant. Pagano has given us a way in to a feeling that is beyond words, and yet we all know what it is when we have it, and know what it is to be bereft of it. Words matter, and it is no small miracle that Pagano’s offer a safe harbor.

Lauren Goldenberg is Deputy Director at the Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers at the New York Public Library. A former book scout and bookseller, she's a lifelong New Yorker with stints in Chicago and Paris.