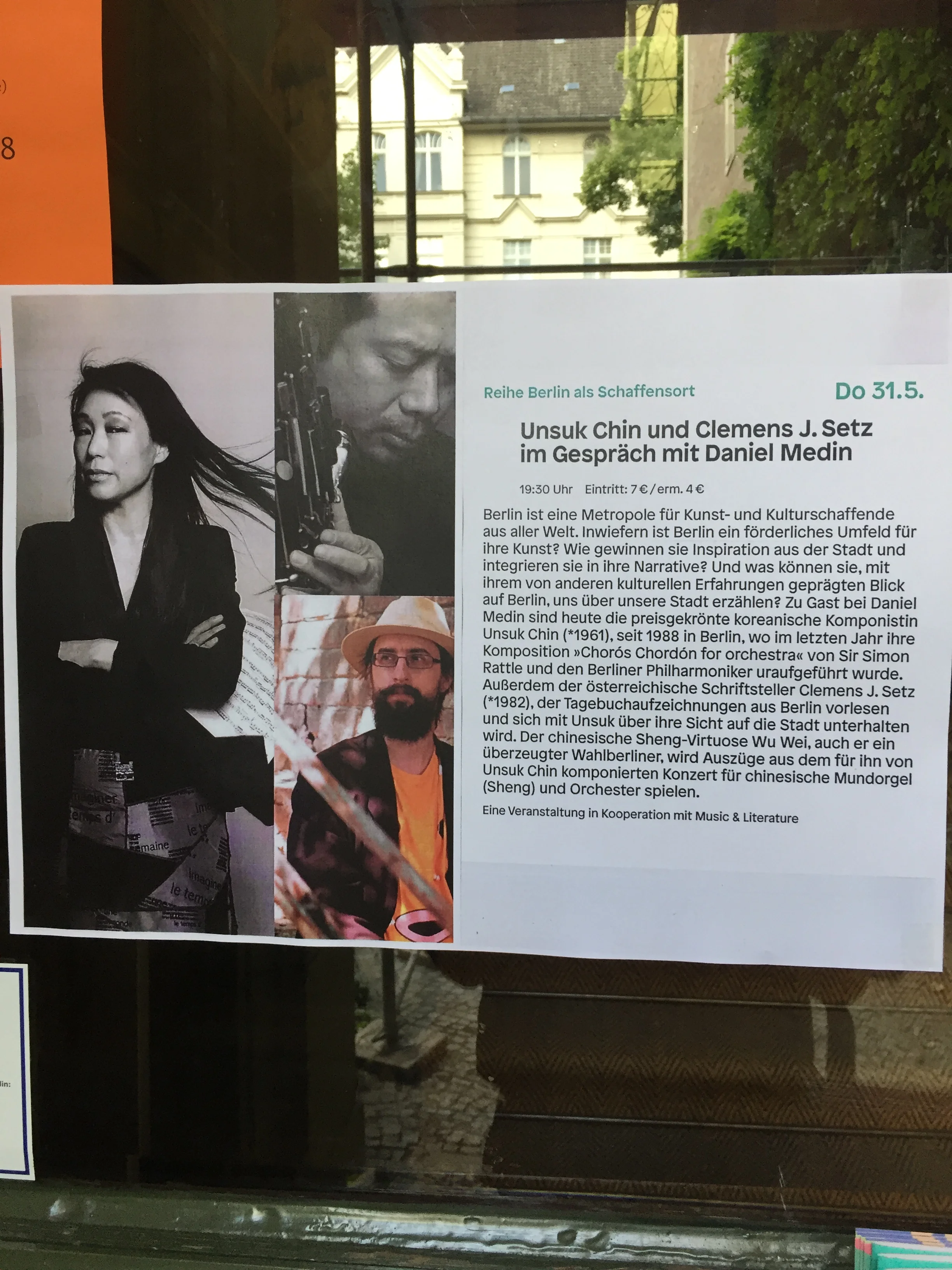

berlin als schaffensort / berlin launch of M&L no. 8

literaturhaus / 31 may 2018

Janika Gelinek (r) welcomes the guests to Literaturhaus and introduces the Berlin als Schaffensort series

The evening of May 31 was a sweltering one by Berlin standards. The ten-degree departure from the historical norm provided not only an extraordinary setting for the second installment of the conversation series Berlin als Schaffensort (“Berlin as Place of Creation,” or, if you prefer, Berlin as Creative Home) and the Berlin launch of Music &Literature no. 8, but also a fitting metaphor for the event as a whole. Conceived as conversations between Berlin-based artists about their creative relationship with the city, this segment broke the mold by inviting Clemens J. Setz, an Austrian writer who, as he cheerfully pointed out, had neither lived nor created in Berlin, to speak with and about Korean-born Berlin composer Unsuk Chin. Above all, however, it is the artists themselves whose work is so maverick, as the evening was viscerally and unforgettably to demonstrate.

After a short introduction by Janika Gelinek, director of the Berlin Literaturhaus, the moderation was turned over to Daniel Medin, who began by reading part of Kent Nagano’s appreciation of Unsuk Chin from no. 8. Though the text was read in German, it is worth picking out some words from Shaun Whiteside’s English translation, as they are the words that seem to come up over and over again in relation to Chin and her work: idiosyncratic, diverse, unconventional, magical. Clemens Setz’s response to Chin’s work was also marked by an almost mystical fascination, and a conviction of its uniqueness. In fact, Setz admitted to having come to Chin partially out of a curiosity about her influences: much has been made of the fact that Chin studied under György Ligeti—and nearly as much of the insufficiency of this intellectual heritage to describe her music. Setz described first hearing Chin’s Akrostichon, and being drawn to it out of an abiding interest in music that plays, as the latter does, with language and text—the evening’s first example, perhaps, of the productive potential of the breaking of creative borders and genres. Chin’s Piano Etudes were more than interesting to Setz, however: he described himself as “obsessed” with them, and read his whimsical yet heartfelt essay from the issue, which recounts the almost out-of-body experience listening to the Etudes provokes in him.

Clemens J. Setz and Unsuk Chin

For the next while, the focus was on Setz, whose unorthodox projects and turn of mind provided a pleasant complement to Chin’s. Setz’s most recent book, Bot: Conversation without an Author, grew out of his curiosity about whether the volumes of diary entries he has written over the years would allow him to be “reconstructed after his death.” The question—posed, like all of Setz’s comments and observations, with the utmost sincerity—found its affirmative “answer” in the book, which comprises a long interview with a “Clemens Setz-bot” derived from Setz’s writings. When Setz read some diary entries having to do with Berlin—from the perspective of a tourist, rather than a resident—it was not hard to imagine such texts as capable of expressing his unique personality: unpretentious to a fault, Setz read off his phone and delivered witticisms and intriguing observations with an earnestness and humility so dry it threatened to cross over into irony.

The outsider perspective having been thusly represented, Medin asked Chin about her journey to and relationship with Berlin. Chin explained that though she had come to Hamburg from Korea to study with Ligeti, she had heard from a former professor in Korea that Berlin was the real place to be, and—since Hamburg hadn’t suited her and by that time Ligeti had gone into retirement—she determined to move to Berlin, which she did with the support of a DAAD grant. Chin also found Berlin difficult at first, however: she was living in Frohnau, in the extreme North of the city, it was 1988, and there was palpable tension, soldiers everywhere, a “thickness in the air.” On the other hand, she suffered no culture shock because, growing up in South Korea mostly under dictatorship, she “didn’t know what culture was,” and only noticed that a few things were different in Germany: “that every sneeze receives commentary,” for example, which provoked laughter from the audience. In reality, it was a slow process of assimilation, she said, and it took 10 years before she realized how much Berlin really offered her as an artist. It was in Berlin, for example, that Chin met Wu Wei, a virtuoso on the sheng,a Chinese reed instrument. After meeting Wei at a friend’s wedding and hearing him play, she immediately vowed to write a piece for him. This turned into Šu for sheng and orchestra.

Wu Wei performs Šu, Unsuk Chin’s composition for sheng

Segue to the third movement of the evening, which was at once the most memorable and most difficult to describe. A sound, at once full and penetrating, entered the room from a distance, nearly imperceptible at first, but growing steadily in intensity until its power nearly overwhelmed the room, then fading once again to nothing. These first notes reminded me of the third movement of Messiaen’s Quatuor pour la fin du temps, but the comparison soon fell laughably short. Wu followed the sound into the room, his eyes closed, blowing into an instrument the size of a large log, which he held vertically in front of his face. After a slow procession to the far side of the “stage,” the piece and instrument blossomed, producing so many different sounds and effects that it was hard to believe they all came from the same source. The sheng sounds at times like a simple clarinet, at times like an organ, at times like some kind of electronic instrument. With 37 pipes, and therefore the ability to produce up to 37 different tones at once, it can generate close harmonies—a possibility Chin’s piece exploited. The sheng is the traditional Western wind musician’s nightmare, as all sorts of skills otherwise considered “extended” or virtuosic techniques are native to the instrument: double- and triple-tonguing and circular breathing are only the beginning. In fact, the experience, for both performer and listener, went far beyond music. As Wei played, his body rocked and wove dramatically from side to side, he hopped and bobbed in a manner that reminded me as much of martial arts as of dance. Such acrobatic movements are partially necessitated by the weight of the instrument and the difficult balance required to hold it, but they also seemed an integral part of Wei’s musicianship and of the piece itself.

This feeling of integrity was one of chief hallmarks of the evening. Wei’s performance, which in the hands of another artist might have seemed gimmicky (to say nothing of the fact that few artists would be remotely capable of playing such a demanding piece), was given with such honesty, dedication, and humility, that it was impossible not to be spellbound. When Šu was over and the inevitable applause erupted, Wei accepted little of the glory, bowing modestly and indicating that Chin should be the audience’s real object of praise. Afterwards Setz, who like so many of us had listened to the piece with an expression of incredulous enjoyment on his face, asked Chin how one goes about composing such an astonishing work. “It’s really not possible to say how one composes,” she answered, but explained that she had taken a few weeks to understand the principle of the instrument—its “silky, slightly metallic sound” and technical possibilities—then had worked from a harmonic idea and a concept which imagined the whole orchestra (which accompanies the shengin the full version of the piece) as itself a sheng, and the combination of sheng and orchestra as a “hypersheng.” The actual composition took 8 weeks. Chin also made clear that her interest in composing a work for shengwas driven by a fascination with the sound of the instrument and in pursuit of the new, rather than by exoticism or some idea of world music. The audience was left with the strong feeling that more than Berlin, the themes which truly unite Chin, Setz, and Wei are integrity, individuality, and daring in art: a drive to explore and experiment, to draw influences from as wide an array of sources as possible, and to break with norms and through boundaries, but that this is done out of pure, authentic curiosity and devotion to art, rather than for the sake of breaking rules. All three artists seem above an interest in wide public appreciation, but happily—at least in Berlin—they have earned this appreciation indeed.

—Anne Posten

Special thanks to Literaturhaus Berlin for their sponsorship of this event.