A feature by Ayşegül Savaş and Amanda Dennis

The project was to resuscitate the letter form, on the topic of how our first novels engage with the urban space of Paris, where we both live and work. The letters took on a life and direction of their own, as we found our way into a conversation about the writing life and the pleasures of making fiction out of spaces and encounters.

A feature by Mark Haber

Agustín Fernández Mallo’s most recent novel, The Things We’ve Seen, is hard to describe. I don’t mean it’s indescribable or obtuse, or a novel that’s difficult to approach; in fact, the novel virtually begs the reader to immerse themselves in the countless stories that cross borders and oceans and sometimes leave the earth’s atmosphere. Yet, like the best of Sebald or Krasznahorkai, any attempt at summary feels like a disservice; there’s too much contained within its pages, too many digressions, both large and small. It’s a challenge to encapsulate a novel that bursting at the seams with such daring imagination.

A feature by Eugene Ostashevsky

How was it different to work on The Pirate Who Does Not Know the Value of Pi as opposed to Rivale, your recent chamber opera for female voice which plays with Baroque music and Baroque poetry?

It has been very important to me—this episode of my life that involved your book—because my work is divided, in general, between new pieces that are, let’s say, explorations of still unknown realities and pieces that I consider analytical. An example of my analytical pieces are Lezioni di tenebra, which is my analysis of the manuscript of a baroque opera by Francesco Cavalli, Il Giasone. When I find myself in front of a text as complicated as your Pirate poem, in both prose and verse, in a language that is very complicated for me, not because it is English but because this English is extremely elaborate, I can say that my composition is more like an analytical investigation of my reading of the text. This approach is part of my work: even the pieces for solo viola are analyses of something that I don’t understand.

Of course, given my experience and my contact with you, I knew that I could do a piece that was both a comic opera and an analytical work that was faithful to my idea of theater of instruments. But at the root of all this was the desire to climb a mountain: for me, reading the whole poem was incredibly complicated, not to say impossible.

A feature by José Vergara

Alisa Ganieva: I always return to the idea that the main character of my novel is not Shamil or any other human. It’s rather the region itself, the space of Dagestan as a whole, and the Caucasus as a region with all its voices and ethnic minorities and wine and crowds and all this multiplicity of positions and perspectives. This is what makes up the main character of the book. You mention that Shamil looks nonchalant. I think many of my characters seem too passive, maybe. They’re not as active as heroes used to be. They’re perceiving the catastrophe going on around them as if it’s normal. They’re not trying to resist it at first, and this way of presenting my characters as groups, instead of individuals, without their own complicated psychology, was a conscious move on my part, because that was the way I was trying to catch the shifting reality of the Caucasus.

A feature by Mauro Javier Cárdenas

All this, of course, Silvina reads, indeed his whole history, originated in the distant past, said Korin, and here Antonio rewinds the recording of Silvina reading from War & War by László Krasznahorkai, trying to remember where he’d recorded her, all this, of course, Silvina reads, indeed his whole history, originated in the distant past, said Korin, no, Antonio thinks, he can’t remember where he’d recorded her so he rewinds the recording to the beginning again, listening to Silvina’s voice again and thinking of Krapp’s Last Tape . . .

A feature by Taylor Davis-Van Atta

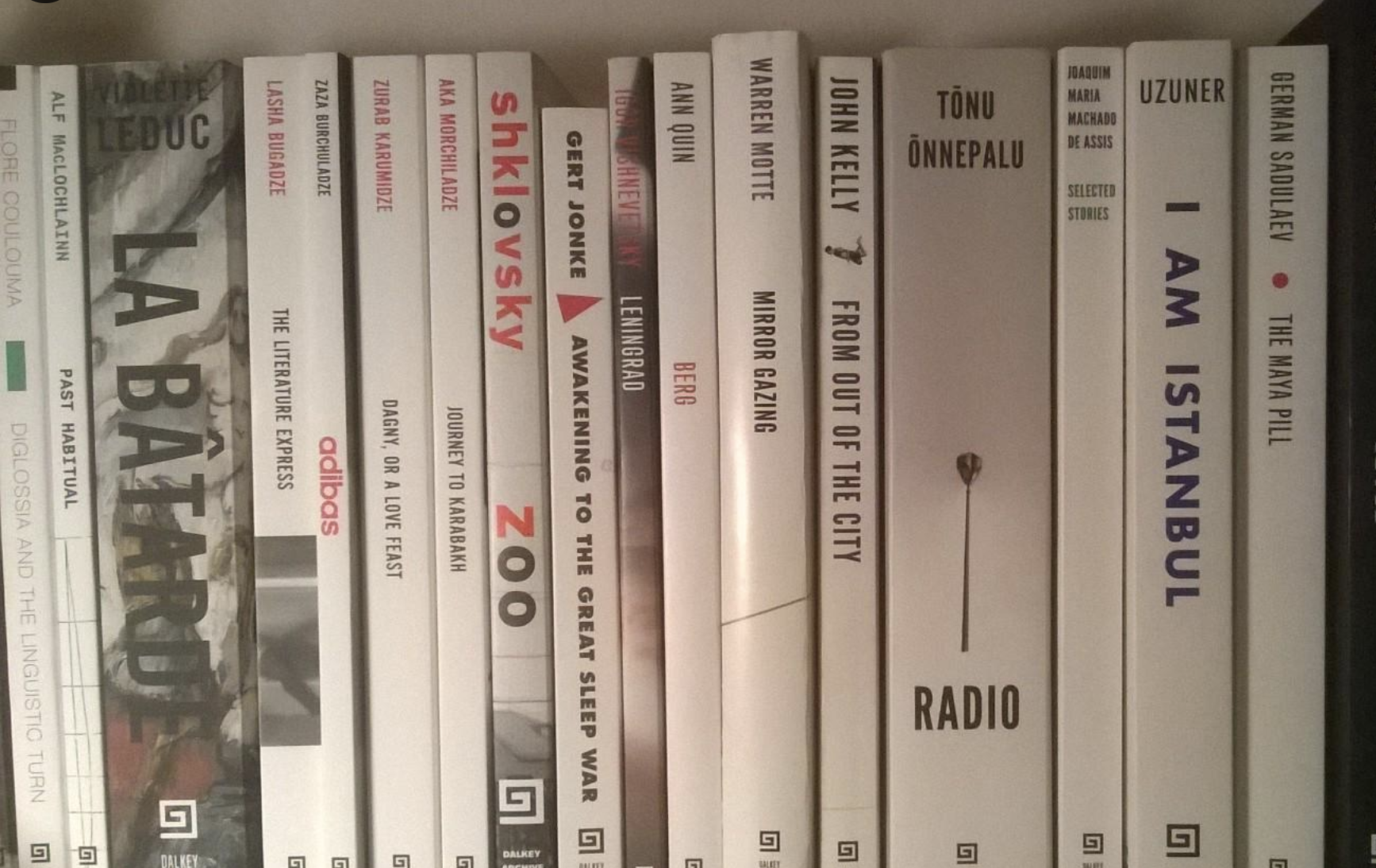

My view is that literature is an international art form and that any serious reader needs to read a novel, for instance, in light of all other novels if one is to gain the full benefit of what a particular writer or work is up to. I like fiction that is doing something different from what I have seen before, this is the kind of fiction that delights me, even though it may also elude me in many ways. It’s not just that great literature can come from almost anywhere, but to appreciate and enjoy a particular work means, I think, that you are reading it against the background of so many other works. But this is true of the other arts as well. The more you have listened to music and the more that you know about it, the greater is the pleasure. And of course with music of painting, one doesn’t say, “Oh, Bach is German, how can I possibly listen to him since I’m an American?”

A feature by Eugene Ostashevsky

Every historian or archaeologist selects and arranges the fragments they use to serve a purpose. To describe the sequence of assaults that eventually took the Passchendaele Ridge. To analyze the assumptions, intel, and pressures that drive commanders in theatre to make the decisions they did. To illustrate, at the level of the individual soldier, the unimaginable horrors and tedium they faced on a daily basis. I guess I arranged my fragments for a different purpose—as a means, not an end. I began with texts from two kinds of manuals, military and spiritual. I trusted that if they seemed connected, and I had been deeply interested in them for decades, something would appear through and in language. Maybe I would find a way in to ground, and into a time, that I could not see.

A feature by Diego Azurdia

I never know where I will land next, but now that you mention the labyrinth, I remember that beautiful parable by Borges entitled “The Two Kings and the Two Labyrinths.” One Babylonian king orders his subjects to construct an impressive labyrinth. When an Arab king visits his kingdom, he asks him to explore the labyrinth in an attempt to mock him. When the king finally reaches the exit, exhausted, he promises to one day show the Babylonian his own version of that labyrinth. Soon after, he launches an attack in which he captures the Babylonian king. He then proceeds to take him on a long camel journey before he releases him in the desert, where he dies of hunger and thirst. After reading your question, I was reminded of Borges’s perfect parable and thought that that might be where I am headed: to that point where nature becomes the perfect, inescapable labyrinth. Natural History already begins that movement away from the library and into nature. At the end of the day, nature is nothing but an archive, full of strata that depict the traces of untold stories.

A feature by Cam Scott

Jazz, one understands, is freedom music. As an art form of African-American origination, fashioned in the crucible of Jim Crow and the endless aftermath of the transatlantic slave trade, jazz has always demonstrated the immanence of creative resistance to any instance of oppression. As historian Gerald Horne writes, jazz “is the classic instance of the lovely lotus arising from the malevolent mud.” For this reason, however, a dubious American nationalism tends to inform popular understandings of the form. Jazz spans the world, not as an American export, but as a music of African provenance, distributed by the machinations of empire. Defying the historical strictures from which it originates, this plural music issues a deep and de facto internationalism, anti-colonial at its core.

A feature by Stefano Nardelli

The rudiments of Lucia Ronchetti’s musical education took hold in the residence of her childhood neighbors, the Bevilacquas—a small, dark apartment full of loose gears and the wreckage of broken clocks. The second child of a large family of modest means, the composer was born in Rome on February 3, 1963, and was three years old when the Bevilacquas, a quite elderly couple, took her in. Mario Bevilacqua, an amateur violinist and composer, had made watchmaking his profession out of necessity. His wife Leny Hanh, a Swiss national, was also a musician, and it was at their encouragement that little Lucia experimented with the sounds produced by different instruments while absorbing the faith the couple held in the redeeming power of music.

A feature by Martha Anne Toll

Hough has had a stellar musical career. Winner of the Naumburg Competition and a MacArthur Fellowship, he holds a thriving international presence as a soloist and chamber player, a rich discography, and more awards and recognition than space permits. Hough is a composer and performer, as well as a highly educated student of myriad musical genres. His tastes are wide-ranging and his repertoire capacious.

A feature by Ida Lødemel Tvedt

What is that about?

I have always made sure there was room for solitude in my life. But not consciously. It was only later, looking back, that I saw the decisions that I made had to do with that. But at the time, when I was twenty-two years old and I chose to stay in the country while my friends were going to the city… What was that about? I didn’t, at that time, understand, but later I did. I have made hard choices, I have given up, I think, a lot of opportunity to make sure I had the time I needed in order to be.

A feature by Brian Evenson

There are certain literary figures who establish themselves in the public eye, who become over time readily identifiable as the face of a movement. It’s almost impossible now to talk about existentialism without thinking of Jean-Paul Sartre, for instance, or to think of literary modernism without James Joyce and Virginia Woolf springing quickly to mind. Once you begin to interest yourself in a movement or school and dig deeper, however—once you begin to consider how a literary or philosophical movement developed—other figures start to gain prominence. You begin to realize that there are other people who were crucial to the development of, say, modernism—indeed, were once seen as central—but faded from visibility with time: Wyndham Lewis or Henry Green or Dorothy Richardson, for instance.

A feature by Éric Chevillard

The coronavirus has embedded itself like one of those secondary characters that the novelist no longer knows what to do with, even though he had assigned him only a lowly or insignificant purpose. How to get rid of him? This miserable wretch has settled down right in the heart of the action. Now he’s calling the shots, dictating the destiny of all the protagonists: I won’t just have to live with him, I’ll have to treat him like the main character, the hero! Nothing will be left for anyone else. At the end of the day, the story will bear his name as its title.

A feature by Éric Chevillard

I thought my little joke about the Zorro masks, which opened this column three weeks ago, was original. No sooner was it published, however, than I began to receive numerous photocollages, drawings, and sketches showing all too clearly that the same idea had germinated simultaneously in multiple brains—as was the case with the invention of photography, and of the phonograph, and even of photosynthesis, which was apparently conceived at the very same moment by a tree fern in La Réunion and a poplar in Maine-et-Loire that had never met one another.

A feature by Éric Chevillard

My older daughter doesn’t like Jerusalem artichokes, her younger sister doesn’t like rutabagas, and just you try preparing a meal in such conditions! All in due measure, of course—except that we’ve lost all sense of measure: our compasses spin endlessly in a vacuum, our tape measures are the streamers of an undertaker delighted by so many mensurations. All out of due measure, then, our current situation calls to mind the great historical restrictions, the siege of Paris, periods of war and occupation.

A feature by Éric Chevillard

We’re still allowed to go out, briefly, for the necessary daily walking of our pets. Let us note that the dog calls “walking” what the human calls “defecating,” and that he requires the street, even the whole city, to deposit his waste—while for us, on the contrary, this rite, this duty, is normally our only daily experience of confinement, in the little room at the end of the hall. In short, this pressing necessity is an occasion for the dog to get out of the house for a spell, and a good reason for his master, on the contrary, to come home running. In both cases, you might say, we get to stretch our legs.

A feature by Éric Chevillard

Confinement’s strict discipline shows us who we really are. Here we are at last, beheld by our own four eyes. That’s right, four eyes, because at least two beings at once are incarnate in each of us. The first one is all nerves, pacing back and forth, biting his fingernails to the quick and then the bone, impatient and furious, while the other one philosophically lets his wise-old-sage beard grow (the metaphor works for comely young ladies too, age and gender meaning nothing anymore) and tries to find something positive in this radical experience.

A feature by Éric Chevillard

I call her Lachesis. It’s a pretty name, I feel, for a spider. For a few days now, in an effort to break up my isolation and not limit my affective interactions to the three members of my family secluded with me, I’ve been working on taming her. Her silk thread is the last link connecting me to the world.

A feature by Chase Kuesel

On July 7, 2013, Keith Jarrett bracingly took to the stage at the Umbria Jazz Festival in Perugia, Italy. The momentousness of the occasion was not lost on anyone: just six years earlier, Jarrett had become the first artist to ever be banned from the festival by director Carlo Pagnotta, for delivering a profanity-ridden condemnation of photographers in the audience. Seeking to avoid a similar incident this time around, Pagnotta issued a preemptive plea to the crowd to put their cameras away and to greet Jarrett with a standing ovation.