The Zaar is an African micro-religion that arose in the eighteenth century in what is now modern day Sudan and continues to survive in small pockets around North Africa. It is a sect that can lay claim to many distinctions, among them that it is an entirely matriarchal religion. Under the aegis of a “spiritual hospital,” women who challenge male authority, as well as gay men fearing retribution from their intolerant peers, have found shelter in the homes of its priestesses who, as a form of treatment, perform song and dance to rid the body of evil spirits.

In 1944, an agriculture student at the University of Cairo named Halim el-Dabh was wandering the alleys of Giza in search of local music. In tow he lugged a wire recorder lent from the school’s radio station where el-Dabh sometimes volunteered. The North African campaign of the Second World War had ended a year earlier and the retreating army of the Third Reich had left behind a surplus of technology—along with the wire recorder the station housed a state of the art magnetic tape machine capable of storing all of its broadcasts. It was also capable of extracting the recorded information from the wire recorder, which could not naturally be played back. El-Dabh’s apprenticeship at the radio had given him a rudimentary knowledge of how the equipment operated—the recorder used lead wire transistors to etch sound onto steel plates. These recordings could be transferred to a tape machine which could play the recording through a speaker.

During his wanderings, el-Dabh came across the frenzied cries and claps of the Zaar song and dance. He attempted to investigate, but the ceremony was private and he was not permitted to enter. In a flash of inspiration, el-Dabh purchased a burka from a street vendor, and, draping the cloth over his head and face, snuck into the ceremony, taking the wire recorder with him.

When el-Dabh returned to the radio station, he began to transfer the wire recording to tape. While fiddling with the console, he discovered that he could manipulate the recording by adjusting the speed and direction the tape was played. Using another tape machine, el-Dabh recorded the treated tape, creating a work that gradually detached from cries of the exorcism he had captured on wire to something otherworldly. He called his piece Ta’abir al Zaar (“The Expression of Zaar”). Included in a Cairo exhibition of Egyptian surrealism that same year, it glimpsed into a possible future of music that has largely come to pass. What Halim must’ve realized, and what modern composers now take for granted, is that a recording was not the end of a work of music, it was just another beginning.

Music of the twenty-first century’s most provocative progression has been the widespread use of digitized audio editing tools, programs such as Ableton and Logic which give a composer or producer endless possibilities to augment sound. Things like sampling, looping, effectation (reverb, delay, phasing, etc.) are largely the result of discoveries made by twentieth-century composers through the use of aleatory occurrence—and more importantly, magnetic tape. If, for example, post-war musique concrètists never had access to tape machines, you wouldn’t have modern pop music. A bold claim, but here are two reasons why. Guitar effects, manufactured processing units modeled off tape procedures, facilitated the psychedelic rock and roll of the 1960s. And the idea of sampling—taking a piece of sound and deploying it repetitiously, this is cornerstone of contemporary pop and hip-hop.

But there is a big difference in employing sound within a composition, and isolating it for study. Tape music celebrates the latter, and its enthusiasts are diehard. This year, the San Francisco Tape Music Collective, the current incarnation of the historic San Francisco Tape Music Center, hosted its annual festival of “audio art” and “fixed media compositions,” a celebration of automated, collaged, and algorithmic music triggered by the press of a play button. To break that down, these included: a collage of recordings made on optical film in the 1930s, Brownian motion sonification, oscillating filter bank drones, manipulated bandoneon music, processed gamelan, samples of Tejano and synth-pop music, and a Frank Zappa classic. Aside from Zappa, the names listed on this year’s three-day bill included tape music luminaries Brian Eno, Pauline Oliveros, and Luc Ferrari. On the stage and around the room were several loudspeakers—twenty-four in all—that could each be patched to an individual channel of sound, allowing for intricately layered music. (Eno’s composition Golden, reportedly made explicitly for the festival, only used a mere sixteen.) The major omission from this gathering wasn’t conventional instruments or their mentation or music, but the musicians themselves. What this was and is, really, is America’s (and perhaps the world’s) only musician-less music festival, a three-day listening party. The composers, aside from a few milling about in the audience, are mostly absent from the festival, or in Zappa’s case, absent from the living. There is no personality on stage, no performers, the audience sits in complete darkness. Had the festival a tagline, one might have been borrowed from the club scene in David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive when the sounds of a live band are revealed to be nothing more than a recording: “No hay banda. It’s all a tape.”

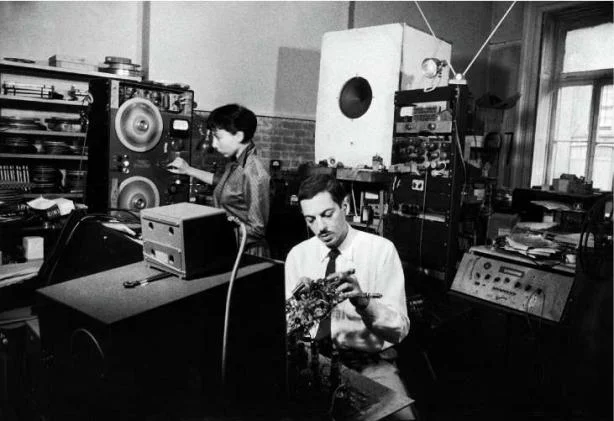

Bebe and Louis Barron

Tape recordings emerged as a way to document radio broadcasts during World War II. The reel-to-reel equipment resembled cinematic film cameras, but these machines were quite large, sometimes filling an entire room. Engineers positioned at consoles could both record live broadcasts or play pre-recorded material by transferring the sound plates from portable wire recorders. Because tape machines were costly, the earliest forays into tape music exploration were done almost entirely at radio stations by composers trusted with the equipment. Experiments with tape first emerged when the French musicologist and sound engineer Pierre Schaeffer founded the Studio d’Essai de la Radiodiffusion Nationale, a covert French Resistance radio station. It was Schaeffer who, after the war, was given carte blanche to experiment with the station’s equipment, thereby discovering sampling, reverse play, reverb and delay, and methods of juxtaposing sound—investigations that provoked the musique concrète movement. His pivotal tape work Cinq études de bruits (“Five Studies for Sound”), premiered in 1948. Musique concrète also influenced early Japanese experimentalists such as Toshiro Mayuzumi, whose Works for musique concrète x, y, z appeared in 1953.

That same year, in America, tape music greatly took off thanks to the husband-and-wife team Louis and Bebe Barron (no relation). The Barrons were a Greenwich Village anomaly—futuristic bohemians. To step into their apartment was to step inside a control center of tape reels, switchboard consoles, wire recording equipment, and other machinations for information manipulation. Their initial admirers included Henry Miller, Tennessee Williams, as well as Anaïs Nin, who worked with the Barrons on her first audio recordings. The Barrons also provided the sci-fi sounds to the 1956 MGM film Forbidden Planet, a score which MGM refused to credit as musical—a snub which caught the attention and ire of John Cage. And it was the Barrons who, along with David Tudor, Morton Feldman, and Earle Brown, helped Cage to record and edit his first tape music piece Williams Mix. Using the I Ching, Cage conceived of a 193-page “dressmaker’s pattern” which would guide the cutting of the tape.

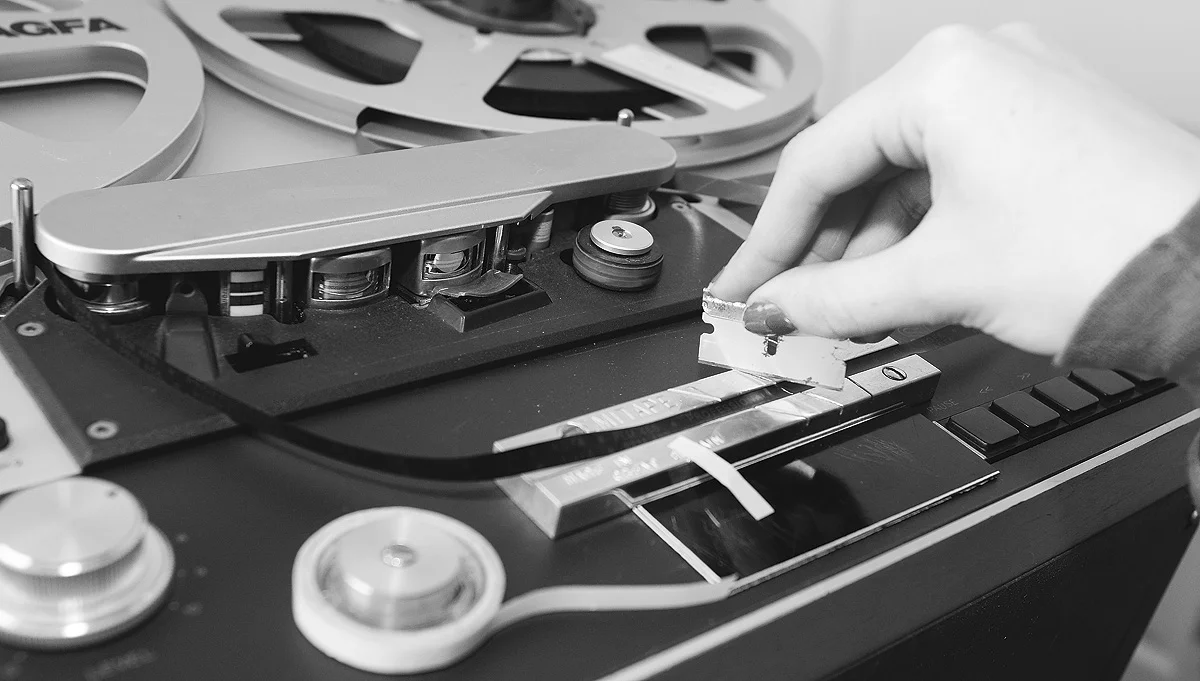

Information is stored on tape by electromagnetic signals imprinting upon an oxide powder that covers the ribbon and resembles events marked on a timeline shrunk down to a microscopic level. Early audio editing was a bit like carpentry, in that it required rulers, razors, cutting blocks, and adhesive equipment. Using these tools, the six-minute Williams Mix was reported to have taken a year to assemble—a composition that required as much technical savvy as it did musical discipline.

“Earle Brown and I spent several months splicing magnetic tape together,“ Cage recollects in Silence. “We sat on opposite sides of the same table. Each of us had a pattern of the splicing to be done, the measurements to be made, etc. Since we were working on tapes that were later to be synchronized, we checked our measurements every now and then against each other. We invariably discovered errors in each other’s measurements. At first each of us thought the other was being careless. When the whole situation became somewhat exasperating, we took a single ruler and a single tape and each one marked where he thought an inch was. The two marks were at different points. It turned out that Earle closed one eye when he made his measurements, whereas I kept both eyes open. We then tried closing one of my eyes, and later opening both of his. There were still disagreements as to the length of an inch. Finally we decided that one person should do all the final synchronizing splices. But then errors crept in due to changes in weather. In spite of these obstacles, we went on doing what we were doing about five more months, twelve hours a day, until the work was finished.”

By the 1960s, tape equipment had become a de facto compositional aid. Cage’s splicing technique was but one of the many uses composers began to find with working with prerecorded music. “It used to be said,” the musicologist Ramon Sender wrote in 1964, “that every composer must confront Arnold Schoenberg’s Method of Composing with Twelve Tones and come to some sort of working agreement with it. Today the composer cannot afford to ignore the experience of working with tape.” Sender was the co-founder, along with his old Mills College buddy Morton Subotnick, of the San Francisco Tape Music Center (the festival is held in its honor), which “offer[ed] a place to learn about and work within the tape music medium.” The SFTMC opened its doors to artists, hosting shows that plugged right into the city’s growing counterculture movement. Among the pieces that made their debut here were Pauline Oliveros’ Sound Patterns, a vocal a capella of galvanic mouths and lips trying to achieve what she called “an electric sound”; Terry Riley’s In C, the seminal minimalist composition; the John Cage and David Tudor collaboration Variations II; and Steve Reich’s monumental phased 1965 recording of a black street preacher, It’s Gonna Rain.

That same year six teenage African American boys were accused of murder during the Harlem Riots. Truman Nelson, the civil rights activist and lawyer for “The Harlem Six,” put together a performance benefit for the boys to pay their court fees and reached out to artists including the self-identified avant-garde of Greenwich Village. Nelson reached out to Reich and handed him the court rape reels from the Harlem Six trials, presumably hoping that the composer might produce a similar work to It’s Gonna Rain.

Reich isolated a segment in the testimony of Daniel Hamm, one of the six accused of murder, in which the boy discusses his wounds sustained during the riots: "I had to, like, open up the bruise, and let the bruise blood come out to show them.” Reich captured and bifurcated the statement “come out to show them” into two separate channels, looping them so that each iteration leaves a residue that builds into a sonic slime. In so doing he was creating an earworm, a bug for protest not unlike Poe’s beating heart. Come Out, isn’t just a historical document used as a solo instrument, it’s also one of the first pieces of protest music for tape, a tradition that has continued to grow in the genre.

The SFTMC’s influence began to color the mainstream. Around this time, major studios were also experimenting with sound production. Abbey Road Studios was equipped with a tape machine that the Beatles used to great effect in assembling musique concrète techniques on their track “Tomorrow Never Knows.” In the late 1970s Brian Eno released one of the most pivotal studio works of tape music, Music for Airports, which he composed with the intention “to produce original pieces ostensibly (but not exclusively) for particular times and situations with a view to building up a small but versatile catalogue of environmental music suited to a wide variety of moods and atmospheres.” The composition played as Heathrow Airport’s background music for many years after its release.

In the early 1980s, magnetic tapes became mass-marketed through playable plastic cassettes and impacted another form of culture: hip-hop. The mixtape was urban samizdat handed around to spread beats and unreleased tracks, and in a full 360 back to radio was employed heavily by station DJs. Among the most famous mixtapes is the Latin Rascals’ 1984 98.7 KISS-FM “Mastermix” which was assembled by employing the same cut-and-paste techniques John Cage used to assemble Williams Mix, collaging together a new strip of samples of then-new acts like Afrika Bambaataa, Kurtis Blow, and Doug E. Fresh, that jump from one sample to the next without ever skipping a beat.

The idea of a mixtape has a powerful hold on pop culture despite a massive decline in the actual usage of tape. “If you think of the timeline and the continuing impact of tape in the last sixty years,” said Lucas Crane, a thirty-five-year-old Brooklyn-based tape musician, “it’s like watching a baby squid grow into a giant with its tentacles going into all these different directions, all of them grabbing onto the ship that was classical music.”

I ask him what he sees as the current purview of tape music.

“Everything is digitized,” he says, “but the image of a clear cassette tape in which you can see the spools and a title scribbled on a narrow strip of adhesive paper is still ingrained in pop culture. It’s like this badass thing, when ten years ago, these same objects might have littered your car floor. But let’s be honest, if I gave you a cassette mixtape now, in 2015, would you have any easily accessible way of listening to it?”

Under the moniker Nonhorse and with a suitcase full of cassettes, Lucas creates live noise collages by sampling from an array of tape decks (up to eight) and processing those samples using an assortment of mixing and looping equipment. His body convulses orgasmically as he performs: he might allow a tape to play on, or slice it as soon as he hits the play button, his hands and fingers flicking back and forth from tweaking and teasing the tape and the mixing dials. A mouthpiece is rung around his face into which he speaks/sings/screams additional fodder for the mix he is creating. He may briefly pause to pop a tape out of a deck to insert another or he might select one without a break in movement. What these recorded tapes sound like untreated is anyone’s guess. He doesn’t sell or give them away.

There are others like Crane who keep not just the spirit of tape alive, but the medium as well. Japan’s Aki Onda also employs cassettes to create meditative environmental music that follows Brian Eno’s creed that “music must accommodate many levels of listening attention without enforcing one in particular; it must be as ignorable as it is interesting.” Birds chirp, a shamisen [a plucked Japanese string instrument] stutters gently within a loop, a woman’s voice announces the time. During a live set in Brussels, Onda performs on a street corner with loudspeakers blaring into the city, but no one seems to mind. People walk by, some stop and listen, others become material—like the sound of a woman’s heels clacking on the cobblestone.

Perhaps the most acclaimed contemporary user of tape is the composer William Basinski, who achieves somber, almost tragic tape music through ingenious uses of subtlety. Around a small board his tapes circumnavigate rounded objects such as batteries to get from one reel to another to which, by applying slight pressure to the battery tops, he is able to alter the tape microsonically with each loop. The results are often thirty-to-forty-five minute suites of music that tonally depreciate in indiscernible degrees, sensed but not outright heard. I once attended a show held at Brooklyn’s Issue Project Room to see Basinki perform A Red Score in Tile, a ten second work that perpetuates for forty-five minutes. Projected on a large screen behind the composer was a video of will-o’-wisps blinking in and out of the night sky, a combination of stimuli that submerged me in deep contemplation, as though I were before a painting whose detail emerged only through a prolonged examination. With his magnum opus, The Disintegration Loops—among the most powerful 9/11-related works of art in any medium—Basinski digitally captured the deterioration of taped symphonic works that erased bit by bit with each revolution, as though one by one members of the orchestra were slowly being put to sleep. The music is set to Basinski’s homemade video, recorded on his Williamsburg, Brooklyn rooftop, of the approaching dusk over the smoldering ruins of the Twin Towers.

This composition offers another kind of profundity: the event that catalyzed our era was rendered most resonantly through technology that had by then entered into its twilight—a document of the future created with materials from the past. Technology is always in a state of obsolescence, with devices, software updates, and apps appearing or announced almost daily. The deus ex machina of tape, its jack-in-the-box surprise, was also its chief modernizer, and in that sense, it could be whatever it wanted, free of historical burden, and ready to remix its history to create something entirely new, even if its physicality has all but disappeared.

Michael Barron has written about virtuosity in electronic music, Balzac's imagined synthesizer, and the jazz novel canon. As a percussionist, he has recorded with Megafortress, Jonas Reinhardt, and Holy Spirits. He lives in Brooklyn.