The contemporary French novelist Antoine Volodine has explored the soul’s migrations and the mind’s liminal states—between humanity and animality, madness and reason, life and death—in over forty books since he began publishing in the mid-1980s. In this article, the French musician and composer Denis Frajerman recollects his twenty-year-long friendship with Volodine and their numerous literary-musical collaborations, the most recent of which was performed last month at the Maison de la Poésie in Paris.

—Jacob Siefring

First encounters

Jacques Barbéri, author of science-fiction novels and my bandmate in the experimental group Palo Alto, introduced me to Antoine Volodine’s work in 1990. Immediately I was drawn into his universe, and imagined a long hypnotic piece of music inspired by Lisbonne, dernière marge, called “Le Montreur de cochons” (“The Pig Exhibitor”). I put together folders of material, took extensive notes on the characters, and hastily began a thorough literary analysis of the text. Being fascinated by entomology, I also had accumulated a large collection of animal sounds, notably insects, that I had collected and recorded over the years. These raw sounds were sometimes altered, sometimes used as they were, set to rhythms I cobbled together in my living room with instruments I invented, and melodies played on old synthesizers . . . My goal wasn’t at all to underscore Volodine’s text but rather to imagine a music for the reader to listen to while reading the book. Above all, not to be limited by the text. I sent this piece of music to Volodine and soon received his reply by fax: he effectively said he had recognized his worlds while listening to the piece of music, the rarest of things according to him, and he encouraged me to continue writing music in parallel with his books. He even imagined a closer collaboration: that he would write texts responding to the music composed in response to his texts, and that I would write compositions based on those texts, and so on. A veritable mise-en-abîme. Galvanized by that recognition from an author whom I respected, along with Cormac McCarthy, as one of the greatest writers of our time, I continued exploring his works through sound materials.

Regarding the “The Pig Exhibitor,” Volodine wrote back: What a feeling of amazement that first listen brought, during which I could SEE ONCE AGAIN my text and also what has always been of the utmost importance to me: mysteries and atmospheres located in the border regions of madness and unearthliness, long waits, internal violence. You embedded all that in your composition. Listening to you, I was transported again back to that place where my writing had previously taken me. [ . . . ] In a certain way, we have both taken the same path through a singular dream.

He also wrote: The complete literary independence of your music [ . . . ] is the mystery of two pieces of work (one in phonemes, one in sounds) that lead back to the same poetic, oneiric center. As if we each had in our possession different keys permitting access to the same magical location. [ . . . ] What occurs during the course of a poetic encounter is not well understood, it involves secrecy and mystery, but it constitutes a miracle [ . . . ] That precious complicity comes from dreams or from nowhere; I hadn’t felt that sensation in years. Your music did that.

At the time I was listening to a great deal of radio, a medium that helped me discover the full potentials of sound through certain radio shows and dramatic adaptations, in particular on the national radio station, France Culture, which I listened to on headphones. I was fascinated by the work sound-effects artists were doing, and how sound was used to conjure up different spaces. Epsilonia, a show that aired on Radio libertaire, was also profoundly interesting, as it drew a link between Burroughs and Ginsberg’s cut-up techniques and the so-called industrial music of the eighties (Cabaret Voltaire . . . ), German kraut rock (Can, Neu, Faust . . . ), and concrete and electro-acoustic music (Pierre Schaeffer, Pierre Henri . . . ).

|

Four Prose Poems by Volodine |

Four Prose Poems by Antoine Volodine, read by the author

(13 minutes)

In 1995 I had the opportunity to compose a segment for a show on France Culture’s Clair de nuit. I proposed a collaboration to Antoine Volodine. He sent me some poems that had initially appeared in the magnificent and now-defunct review Les Cahiers du Schibboleth. I selected four of these, which then became the basis of my work, and Antoine came to see me and lay down vocal tracks. That was the first time we met in person, and I still have to this day a very fond memory of the occasion. He struck me as charming, smiling, and simple. He seemed to radiate an inner strength and a rare charisma.

For the occasion, I composed a piece of music for strings, trumpet, electric guitar, percussion, synthesizer, and magnetic tapes. All the recording was done in my home in a small room set up for making music and recording. Two short string segments began and ended the composition: intro and closing credits. A jingle served to demarcate the piece’s four parts, each corresponding to the four poems. Antoine Volodine astonished me with an extraordinarily hypnotic reading, cleverly imitating several different Central European accents—he is, of course, a former professor of Slavic languages . . .

|

Les Suites Volodine |

Les Suites Volodine

(60 minutes)

I continued to meticulously explore Volodine’s novels. Whenever I finished a piece, I sent it to him, and he wrote back to describe his impressions and his delight upon hearing the new composition.

Travel effected by means of a long, lancinating ascent. You arrive, and down there, you are born (on “Un Cloporte d’Automne” [“An Autumn Woodlouse”])

It took me two long years to finish what I would eventually call Les Suites Volodine. Two years holed up at home, obsessed by his books and the weird sounds I was creating. A total immersion in the Volodinian universe. After our meeting we had begun a rich correspondence, and I confided in my elder, who assured me with his warmth and kindness. During those years Antoine Volodine became my spiritual uncle, my model (along with the other author mentioned at the beginning of this article: Jacques Barbéri).

Les Suites Volodine was released by a French record company—Noise Museum—in 1998 with a previously unpublished text by Volodine: “Conseils pour le concert” (“Suggestions for the Concert”) . . .

|

Des Anges mineurs |

Des Anges mineurs [Minor Angels]. Post-exotic oratorio for an ensemble of 7 musicians, female singer, narrator, female dancer, and videographer

(50 minutes)

In 1999 and 2000, the book Des Anges mineurs (Minor Angels) won several prizes, including the prestigious Prix du Livre Inter. Jérôme Schmidt, journalist for the magazine Chronic’art, approached me with a proposal to adapt the novel for a literary and musical event he was putting together with his journal in a large Parisian concert hall, La Cigale. I composed a work for cantatrice, voice, strings, saxophones, bass guitar, drums, and tape reels. Most of the tape material was recorded in the chicken coops and stables in my village in southwest France. Slowed down, the milking of the cows and the sounds of the calves sounded like the agonized crying of diabolical, prehistoric or alien animals . . . I was very interested in contemporary dance then, and I imagined an introduction by a shamanic, female dancer. The dancer Keity Anjoure played that part marvelously: entirely immersed in the book, she built a set inspired by Siberian yurts. A spellbinding succession of images by Margo Berdeshevsky completed the visual aspect, as well as little red Chinese lamps set up in front of each musician. Margo introduced me to the extraordinary singer and composer Géraldine Ros, whose stunning, solar voice lit up the performance.

I’ve always thought of myself as an artisan, mostly uninterested in technological progress, my home studio being constructed from so little material: an old eight-track tape recorder (which regularly stopped working, thereby rendering the tapes themselves useless, and requiring me to re-record everything—Volodine called my studio “Le Nautilus” because of that!), a K7 four-track recorder (which I used to process the magnetic tapes), various guitar pedals adapted to my purposes, a little reverb. . . At present my setup has grown to include a 24-track digital recorder, but I still can’t work on a computer . . . Everything in my compositions is played live, nothing is programmed, and when there are errors in the performance, I often don’t correct them but mask them with bizarre sounds . . .

|

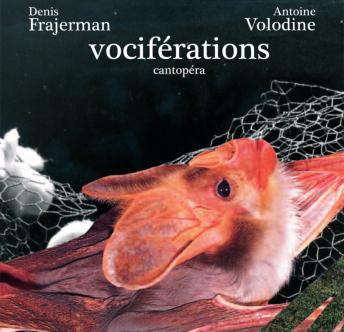

Vociférations |

Vociférations, cantopéra

(70 minutes)

In 2004 Antoine proposed a collaboration that he submitted to France Culture for the show “Les Ateliers de Création Radiophonique.” He had written a long incantatory poem inspired by Maria Soudayeva’s book Slogans, which he had recently finished translating. Volodine wanted the style of the music to be powerful and operatic, with a brass section. I started working on a piece for thirty musicians but had to decrease that number for budgetary reasons . . . I had actually imagined that I would write an opera, before even having met with the producers . . . Sometimes I was a little overzealous! In the end I replaced most of the instruments with synthesizer (certainly the brasses), and arranged the musical drama for drums, saxophone, violin, viola, cantatrice, magnetic tapes and voice (Volodine’s). Most of the instrumental parts were recorded at the Maison de la Radio, in Paris, equipped with the excellent technical capabilities of the sound engineers there, and Antoine recorded his text flawlessly in a single take! A veritable actor’s performance. I recorded the keyboards at home on a K7 four-track, my eight-track tape recorder having recently broken . . .

In our correspondence we spoke during a certain period of the practice of sport. Volodine was assiduously training in Budō (Japanese martial arts), and practicing sword-handling, a very physically demanding and difficult art, he said. Meanwhile, I was swimming a lot and my intensive training provoked hallucinations during the naps that followed. I dreamed that my body split in two and was floating . . . Then I awoke into a second state and made post-exotic music. Sometimes I would dream of the music, wake up, and the music would already be there, sounding just the same as before in my dream . . .

After the broadcast of “Vociférations, cantopéra,” a concert version of the piece was performed with five musicians in Nantes at Le Lieu Unique, a French national heritage site.

|

Terminus Radieux |

Terminus radieux [Radiant Terminus], cantopéra

(49 minutes)

In September 2014, Antoine Volodine informed me that the Maison de la Poésie in Paris was giving him carte blanche to put something together over three days in April 2015. He wanted me to be involved in the project in whatever musical capacity I preferred—a performance of one of our previous collaborations, perhaps . . . I quickly settled on a creation with two female lyricists, a celloist, and a guitarist (me). Volodine suggested that we do something based on his latest project, Terminus radieux, and more specifically the character Solovyei’s wax cylinders, which were more or less long “divagatory poems.” I read that amazing book numerous times, one of my favorites by Volodine, more than 600 pages in all, and I also read books mentioned in it and related to it, including The Steppe by Anton Chekhov, James Oliver Curwood’s The Golden Snare (how odd to dive back into the work of an author whose work I had read in its entirety as a child!) and Manuela Draeger’s post-exotic Grasses and Golems. I also researched kolkhozes and sovkhozes (respectively, the Soviet collective farms and state farms).

The composition of the work respects the novel’s four-part structure (“Kolkhoz,” “Hymn to the Camps,” “Amok,” “Taiga”) and lasts 49 minutes, to correspond to the book’s 49 chapters. The performance was very successful: the concert hall was packed (a beautiful, 160-seat hall with great acoustics and balconies), and an almost sacred atmosphere reigned for the concert’s entirety. Justine Schaeffer was especially fascinating: a singer with a unique voice and perfect articulation, she illuminated the work with her magic voice. As for Carole Deville—my favorite celloist—I wrote a section just for her: the “mold, pedestal, and sphagnum” of Terminus radieux. Émilie Nicot, mezzo-soprano, impressed the audience with her vocal strength and precision. She collaborates with many professional ensembles, regularly performs as a soloist in the repertory of classical oratorios (Rossini, Vivaldi, Mozart, Bach . . .) and in operas of all sorts: baroque, classical, romantic and contemporary (Purcell, Colasse, Mozart, Donizetti, Verdi, Wagner, Strasnoy, Rabaud, Lecocq . . . ).

We did our first rehearsals in the home of Justine Schaeffer’s father, the renowned Pierre Schaeffer, in his very study: a true cabinet of curiosities. I am infinitely grateful to Justine and her mother Jacqueline Schaeffer for making that happen.

I have not been recording on magnetic tapes for some years now. Perhaps one day I will return to that medium, but for now I want to write entirely acoustic compositions, without synthesizers. The exploration of the voice—the female voice, especially—is my passion at present. In truth, with each new project I try—more or less successfully I think—to explore new musical paths. Thus, my second album Fasmes (Noise Museum/Naïve, 1999) goes in the opposite direction of the multi-faceted, narrative album Les Suites Volodine: time is stretched to its limit, the sounds go up in smoke and nothing really develops or evolves. I find it very hard to listen to that album today. Yet certain people, especially musicians, appreciate it . . .

I’ve been thinking about re-releasing the albums Les Suites Volodine and Vociférations along with two of the unreleased studio pieces: Des Anges mineurs and Terminus radieux. That would make for a nice tetralogy. After that I would like to go back into the studio pretty much by myself to record an album that would be a sort of continuation or follow-up to Les Suites Volodine . . . An album using magnetic tapes again, but with very few other players. Patiently constructed in my studio. I should add that the mixing will be very important. That step amounts to three-quarters of the composition.

—Translated from the French by Jacob Siefring

Denis Frajerman started as a composer in the French experimental Band Palo Alto. He now collaborates regularly with storytellers and writers—including and especially Antoine Volodine—for radio performances, oratorios, or records, as well as composing soundtracks for contemporary dance, object theater, animation, short films, and documentaries. He also plays guitar, and is influenced by Greek folk music and southern United States rural blues.

Jacob Siefring was born in Dayton, Ohio. His poetry, translations, and criticism have appeared in Black Sun Lit, The Brooklyn Rail, the Montreal Review of Books, Quarterly Conversation, ohio edit, and Ambos. He resides in Ottawa, Canada, and blogs regularly at bibliomanic.com.