By all accounts, hers included, the Argentine poet Alejandra Pizarnik (1936-1972) spent as much time subtracting words from her poems as adding them. She was perennially mistrustful of her medium, seeming sometimes more interested in silence than in language, and the poetic style she cultivated was terse and intentionally unbeautiful. Her poems are short but rarely easy—they’re too severe and programmatically bleak. Yet recognition came early. Her first collection, The Most Foreign Country, appeared before she was twenty. By the time of her suicide, at age 36, she had published seven more books, including Diana’s Tree, her most celebrated, and The Bloody Countess, a work of fiction (her later poetry is forthcoming, in Yvette Siegert’s translation, in Extracting the Stone of Madness: Poems 1962-1972). Thick posthumous volumes of her diaries and collected prose followed. In Argentina, Pizarnik is counted among the country’s most important poets. Her work is very fine. Yet like Sylvia Plath, to whom she’s been compared, her allure is bound up in her biography—her depression, her bisexuality, her intense artistic dedication, her premature death. The attention to how she lived could be seen as a disservice but it isn’t one. Pizarnik was, in fact, consumed with the subject herself. For all her fears of unreason, she approached her choices seriously, deliberately, and even her maddest, most unhappy decision—her final one—was not without design.

Alejandra Pizarnik

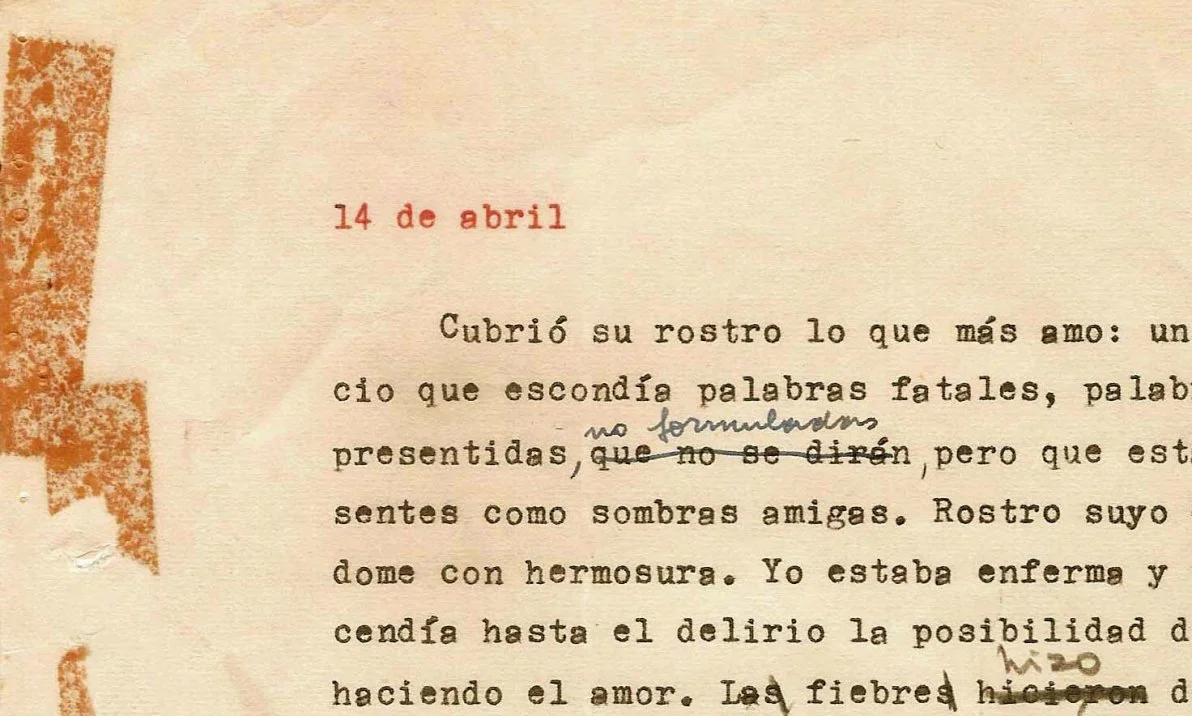

Pizarnik's obsession with the form of her life—how it went, how it should go—is especially visible in her letters to her psychoanalyst, León Ostrov, a selection of which appears below. Pizarnik began seeing Ostrov in 1954, when she was eighteen. The analysis, which lasted barely more than a year, initiated a friendship that remained analytically alive long after it stopped being formally therapeutic. The conversation was not confined to Pizarnik’s “problems and melancholies,” as Ostrov would understatedly refer to the often debilitating mental illness of his former patient. Pizarnik and Ostrov shared their minor doings, riffed on books, discussed Pizarnik’s writing and career. Pizarnik visited Ostrov’s house and grew close with his family. Ostrov’s daughter, Andrea, remembers Pizarnik arriving at an elegant dinner party in a “furiously” red sweatshirt and pants. In 1960, when Pizarnik moved to Paris, she and Ostrov began regularly corresponding, and stayed in touch throughout the four years she lived abroad. The nineteen letters that survive this period (there are twenty-one in total; two date from earlier) showcase the young poet’s wit and spirit even as they reveal her anxieties. Pizarnik complains about her parents, insults her boss, mocks the Parisian literary elite (she’s appalled by Simone de Beauvoir’s screeching voice), wonders whether a poet should live artistically or like a “clerk,” and fantasizes about her artistic future. “I’m numbering the letters for our future biographers,” reads one postscript.

Just five of Ostrov’s responses remain, yet they are enough to show how central and reassuring a figure he was for Pizarnik during her self-imposed exile. At twenty-four, she had forcibly distanced herself from her home. She wanted to act like an adult, she told him, yet she felt uncertain of her capacity to successfully work a job or support herself fully or stay sane—nor was she sure she wanted to do those things. Ostrov was a sympathetic, encouraging listener. He endorsed her impulses toward independence and soothed her fears, organizing and interpreting what she said with tender, sometimes textbook, theories—her feelings about a friend are really feelings about her mother; her resentment of her mother masks a longing for her; the longing is the result of an ancient wound. Throughout the correspondence, the reasons for Pizarnik’s enduring appeal as a romantic figure—beyond her attractions as a poet—are obvious. She’s essentially radical. She’s as proud of her unfitness for ordinary life as she is anxious about it. How can she, who lives “passionately on the moon,” care about money? Why go outside if she can read all day instead? Her flaws she transmutes into virtues. Pizarnik was, as she is known to have been, tortured and lonely and endlessly self-doubting. But she also had a sense of humor and a flair for drama, not to mention spectacular ambition, and she was on occasion quite pleased with herself too. Sanity and good behavior, she knew, are a drag—and what did she show but that art needs their opposite.

—Emily Cooke

[Letter No. 10]

27 December 1960

Dear León Ostrov:

I’ve wanted to write you for a long time and who knows what impatience stops me in the middle of letters, what exasperation at my poverty of language. In the end, I’m sending you a few lines so you know that I’m here, that I’m alive, and that if I don’t write it’s because I can’t.

My life here is up and down, it’s the usual flow, hope and hopelessness. Desires to die and to live. Sometimes there’s order, other times the chaos devours me. I think right now it’s the latter. Perhaps that’s why I’m writing you.

Alejandra Pizarnik

Work at the office is going well. I’m good at it. I work with absolute lack of focus. But that, apparently, is the reason for my success. I think about the most distant things while my hands and something—who knows what—merges with the task before me. I’m far away, and nevertheless the work gets done. It surprises me I haven’t transformed this job into hell, I mean my relationship with the people around me. I’m polite and silent (très gentille) and my only concern is Eichelbaum (whom you know, I believe), and whom I secretly hate. This hatred exasperates me like all emotional manifestations I don’t understand. With all due psychoanalytic humility I let myself discover—through dreams and associations—that I identify him deeply with my father. In addition, I’ve fallen platonically in love with an Argentine journalist who’s working with him on a radio program. This love was just what I needed to bring the always burning problem of my mother into the present. It should be added that the journalist is a confessed lesbian and that E. meets with her everywhere but the office (“He’s preventing me from seeing her”). All this plunges me into the two usual shadows, the two figures of my childhood, the feeling of orphanhood and the old pain. Only now do I really see and discern it. That is, during the day I understand the pathology of the love (I’ve been crazy about her for three months already), but night has its revenge, and the more I’m “cured,” thanks to my own strength and intelligence, the more I have sad dreams like hospitals about her and my family. In the end, those two figures, E. and the journalist—I don’t know why I’m not using her name, you must know her—are present and near me almost all day and all night. My life, then, is a conspiracy of shadows. I see other people; I try to go out; I make myself go to the movies, the theater; I read; I write. Plus, as of last week I have a lover—a lover who makes me happy. It is so surprising, at the very moment I was feeling exactly in the middle of homosexuality, someone comes (a young poet very similar—in his poetry and his way of making love—to Enrique Molina) with whom I’m reaching absolute physical realization, absurdly perfect. I’m still amazed, how is it possible, I wonder, to be so sick and neurotic and nevertheless permit oneself such bodily exaltation, such sexual plenitude, such deep adventure. All of which is surrounded by fears about the consequences (as usual) and also a strange astonishment because I don’t love the young poet, I am, in short, indifferent, and nevertheless when he visits it’s like a drug, something much stronger than everything else. However, the following day the guilt comes, a biblical feeling of the heaviness of the body, of sex, and I’m filled with memories of doves and need angels and flowers: poems. Everything else is in doubt: I don’t know if I’ll go back or if I’ll stay. They still haven’t told me that they’ve definitely accepted it but I suspect that it will be so; after all, what does it matter whether I go or not—or, better said, what matters is that I don’t go, what matters is the solitude—which I’ve begun to want— of my little room, what matters is my freedom of movement, and the absence of other people’s eyes on what I do. If it weren’t for my infatuation (which many nights makes me roam the streets looking for her: in every face, every tree, in the dogs, the dead leaves, in the shadows; and then the final sadness of returning before having found her, and discovering that, what if that which ought to be doesn’t exist?), my life would be calm and possibly joyful, but instead there is only this new unreality into which I’ve been plunged, this absurd love (as always in these cases, making it so that I can’t remember her true face). In the end, I’m afraid and at the same time delighted, fascinated by what I lack and what is unavoidable about who I am, all that I am, and all the women I am, all those who make and unmake me. (“They suffer but they’re alive. Suffering is reality.”) I’d like to talk to you about all this. Meanwhile, forgive all this conflict, my throwing myself at you through the air, a patient for life, erected on the Eiffel tower like an unwavering “homage to Freud.” Hugs to you, to Aglae, and to Andrea.

Alejandra

[Letter No. 14]

Undated and without an envelope.

Likely sent between July and August 1961.

Dear León Ostrov:

I’m writing to you from Capri, in a café surrounded by boats on a pure blue sea below a pure blue sky. I spent three days in Rome—following your advice—and fell in love with the streets there. I promised myself that I’d return for more time. Now I’m in Capri—it’s my first day—and I feel unhappy. Last month I was so tired I didn’t have the strength to choose a place to stay for my vacation (1 month). Following the advice of my cousin, a student of medicine, I’ve come to Capri for the Club Méditerranée, a sort of travel agency apparently under the influence of Israeli kibbutzim because in place of a hotel there are cabins and all the inhabitants appear extremely keen on communal life. I, more tired than ever, and with no ability to talk to anyone, how can I talk to kids who recall my own stupid adolescence? It’s clear that I’m absolutely exiled from society and I’ve just confirmed that this isn’t a meaningless expression. I simply have nothing to say to them, we have nothing in common. But I’m the one who understands, I’m the one who knows. That is so hard to say. But I also don’t wish to talk. To anybody. I want to see clearly into myself.

I still want to go home (to Bs. As.). Health reasons. Every day I feel sicker, more tired (nothing more than vertigo and fatigue). I’d like to go rest for months. But on the coast of Rome and Paris, what will I do in a city as ugly as Bs. As.? But nothing is alive in the streets. I don’t know, basically, how I’ll stand this month in Capri, not only because of the imbeciles at the club but also the terrible beaches… Another thing that disgusts me is the landscape in the style of classic postcards. No doubt the surrealism pains me… I don’t know if I told you that they’re publishing my poems in the NRF5 and in Lettres Nouvelles. Basically, I’m tired and can’t sleep.

I’m sorry for this vapid humorless letter. I’ve no strength for anything else. Plus now I’m worried about the mix of French, Italian, and Spanish that I use every day. To speak multiple languages is to speak none. It wasn’t for nothing that Rimbaud immediately dedicated himself to language after leaving poetry. That’s how I am, refusing myself Spanish even with the people who know it. It’s been two months since I’ve written a poem. I think it “advisable” that I go back to resting and writing.

I wish I could tell you more. I’ve thought about and seen and observed so much over these days. But maybe I’ll write it. Maybe a story, an article about my discovery of what imbeciles people can be, are. And yet I’m sad about it, sad to realize this, I’m sad and they’re not. If knowing what I do I don’t write beautiful poems… Basically, the conflicts of someone without a personal life.

I’ll write again, from here or when I arrive. “Forgive my sadness.” Hugs to all three of you,

Alejandra

[Letter No. 19]

Paris, 21 September 1962

Dear León Ostrov:

Thank you for your letter and congratulations to you and Aglae on your approaching child. I suppose that in spite of all the revolution and conflict you’re thinking of the name you’ll give him or her. At least that is what I would do because for those who love (or fight with) language, a name is very important. I imagine Andrea is so happy expecting a future companion for her games.

It’s been just a few days since I returned to Saint-Tropez, where I was “resting” for three weeks in Doctor Lauret’s ocean villa. More than the sea and the sun and the pool and the whiskey and the people I met (Italo Calvino, Marguerite Duras) and the ones I eagerly spied in passing (Picasso), I was most excited by a tiny blue motorcycle that the owners of the house put at my disposal. How and why I had not a single accident are questions that make me believe in the existence of something like fate. Dr. Lauret, as I’ve already told you, is my psychiatrist. She also does psychoanalysis—or she used to, I don’t know.

Alejandra Pizarnik

What I’m doing with her is conversational psychotherapy (please excuse my errors or inaccuracies in this realm because I’m ignorant of the nomenclatures). I don’t know if it’s helped so far, I don’t know if it will help. The only change (according to my friends) is so far physical, corporal. My body has improved, changed quite favorably, and, what’s most amazing, my hands aren’t like they were before: their current delicacy almost makes me afraid. On St. Tropez I fell, just like that, into the dreaded transference, in response to a gesture, a look, a special way she had of looking at just-bloomed flowers. Useless to tell you about my present “mystical” state, my hell, my distance, my suffering, my fragility. How sure and hardened I thought I was after these two years of Parisian solitude… None of that, now. Now I’m never alone that I’m not pursued by her image (“et c’est toujours la même, et c’est le seul instant”). If you have Nerval’s sonnet “Artemis” on hand read it in my honor, the first verse will tell you more than this letter).

Yesterday the doctor said, when I talked about your letter, that if you wanted to write to her—about me, naturally—she would be delighted. Here is her address:

Mme. Le Dr. Claire Lauret

7, Rue de Chaillot

Paris 16

Although I imagine that you write French perfectly I can tell you that Mme. Lauret understands Spanish very well.

In the end, if it does anything to whisper a prayer, if there is someone to ask, I’m praying for this to be my last “transference,” my last fantasy love, my last impossible thing. If not I’ll be turned into a fountain, as Malte says.

Naturally I’m writing a lot because of this excessive new enthusiasm. I did a kind of enormous poem in prose—the best I’ve written in my life. It’s a pity I don’t have the strength to edit it or type it out.

I don’t know if I told you that the director of Mito (where they published my diary), Jorge Gaitán Durán, died in an accident in which a Boeing airplane crashed in Central America. We’d been friends—maybe more than friends. He was thirty-five, he was very beautiful, and we’d made plans before his departure, marvelous and possible, that had pulled me out of my unhappiness. His death affected me enormously. Here is the address of Mito:

Apartado Aereo 5899

Bogota D.E.—Colombia

You can tell them that you need number 39–40 for the homage to Borges it has. I, unfortunately, have only one copy—and I don’t know where it is.

My book is going to come out in SUR. I’m anxiously awaiting any news regarding it. They tell me that the post office is on strike. Could you ask them, please, to delay the strikes and coups until my little book is finished?

I share your fascination with Rio de Janeiro. I was there for only eight hours and I still have with me the colors, as if of an enchanted garden; the perpetual formless rainbow; the desire to celebrate when you look at the sky. But it must be rather damaging for “intellectuals.”

My hugs to all three (or all four) and maybe if the post office strike continues by the time this letter arrives there will be five,

Alejandra

Mexico is done in terms of articles. The magazine dissolved. So goes l’Amérique Latine—I’m making extra notes for Cuadernos.

Alejandra Pizarnik was a key figure in twentieth-century Argentine poetry. Her most recent collections to appear in English are Diana's Tree (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2014) and A Musical Hell (New Directions, 2014).

Emily Cooke is a senior editor at Harper's and a writer. Her reviews have appeared in the London Review of Books, the New York Times Book Review, and Bookforum, among other publications.

To read more of the correspondence between Alejandra Pizarnik and León Ostrov, order your copy of Music & Literature no. 6 . . .