“Rut Hillarp was born 100 years ago this past Friday. She is one of the most unfairly marginalized authors in Swedish literary history. It’s as if we refuse to allow ourselves to discover just how damned excellent a poet she is.” — Bernur, February 23, 2014.

“Her lyrical prose is fantastic: so beautiful, erotic, dark, perceptive and intense.” — Swedish novelist Therese Bohman on her female role models, Kulturkollo, 2014.

Some discoveries are almost too delicious to share. We see an author’s name (on the web, on a shelf) and we decide we must read them. There was something to that name (the way the letters looked together or the paper’s grain). From the first line, the words tumble into an order, tantalizing and new, but somehow familiar. An echo we’ve heard before. The words tangle with our thoughts, become inseparable, and we, the curious reader, become devotees. For a time, perhaps forever, we keep the name to ourselves, guarding it as a jealous lover would. But some names ask to be spoken aloud, written in emails and on scraps of note paper with the addendum “must read.” One of those names is Rut Hillarp.

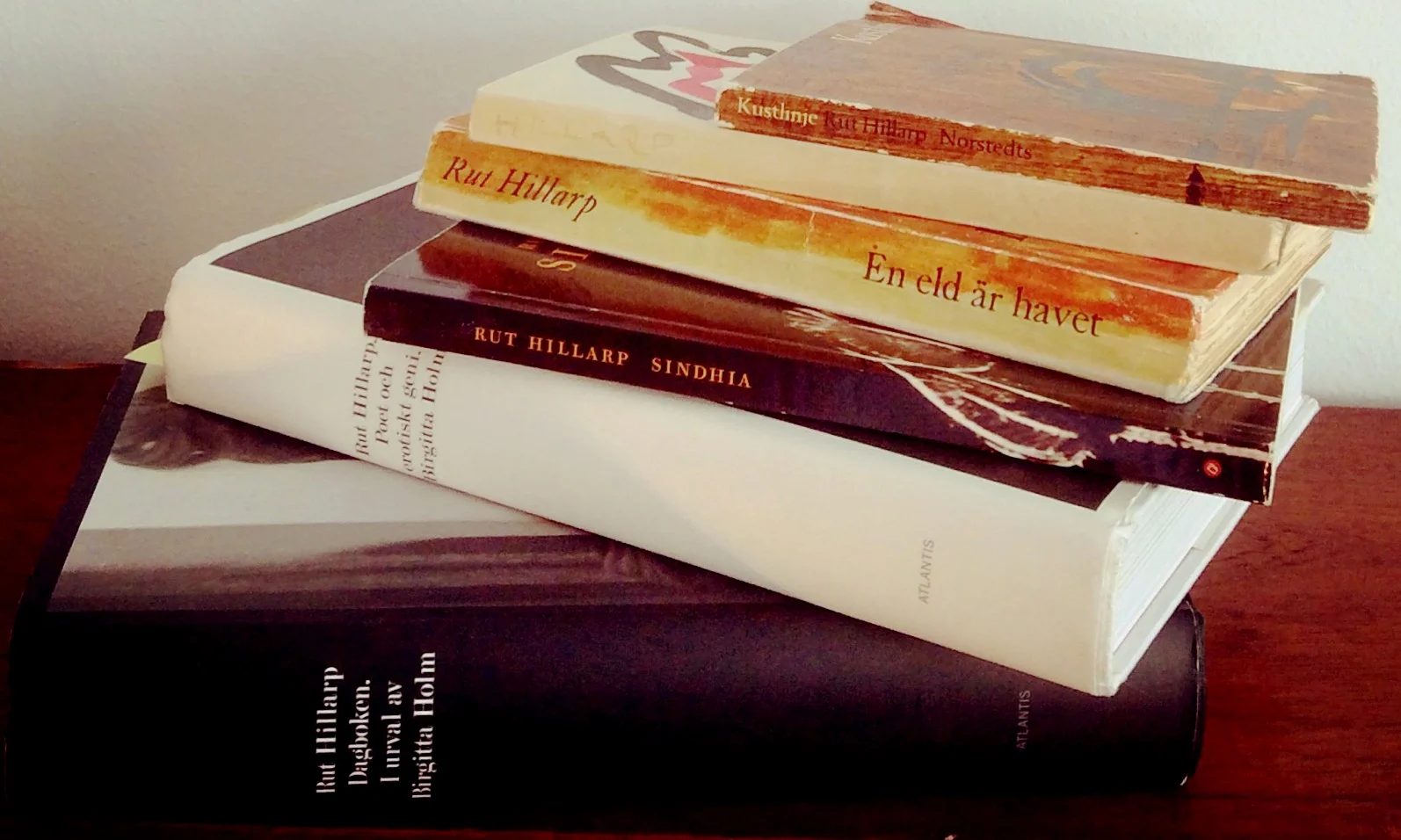

Rut Hillarp—who was she? The year of her birth, 1914, seems so distant, but the year of her death, 2003, still feels like it was yesterday. Five years ago, The Gothenburg Post called her a grand dame of the women’s movement. Rut Hillarp—one of Sweden’s great, yet overlooked Modernists—turns those whom she touches into devotees: her readers, lovers, students and mentees. She is a cult figure, an antiquarian bookseller in Gothenburg told me after I had learned her name and embarked on a mission to possess each and every one of her books. As soon as his shop gets one of her books in (rarely), it sells. None were in stock.

My romance with Rut Hillarp began this past summer when the Berlin-based publisher Readux Books was looking for one more piece to complete their Sex series which was to be published at the end of 2015. Since Readux launched in 2013, the publisher, Amanda DeMarco, has let me scout Swedish stories for their short, small format books, which include contemporary fiction, rediscovered classics, and essays about cities. My translation of Malte Persson’s short story “Fantasy” was my second translation ever—part of a gamble to see if I could turn my ability to speak Swedish, my mother’s second mother tongue, into a career. When I want to feel official, I say I am their Swedish editor. Mostly, I like to call it nothing at all and think only of the special pleasure of reading for love and with purpose, for Amanda.

Erotic culture is a special interest of mine (academically, professionally), and as her deadline drew near I berated myself for still having found nothing. In a fit of frustration (inspiration?), I typed something like “forgotten Swedish eroticist” into Google, thinking that my chances of coming across Sweden’s Anaïs Nin—or anyone vaguely comparable—were slim to none. But there she was: poet, diarist, experimental filmmaker, photographer, teacher, and novelist. And her novels, four in total, are how I would like to introduce her to you here—Blodförmörkelse (Blood Eclipse, 1951), in particular, from which the English translation The Black Curve (Readux Books 2015) is taken. I am not the first to love her, apparently, but I suspect I am the first to have brought her into my mother tongue. To the best of my knowledge, this is the only published English-language translation of her work.

When her debut novel Blood Eclipse arrived in the mail, I barely dared touch it. A slim, brittle volume from an antiquarian bookseller in Stockholm. One of two available for sale online. Self-published in 1951. Number 27 in an edition of 500, with one of 50 covers hand-painted by the author and signed to Nils Ferlin (the poet, I assume). It was love at first line. I let the sun burn my shoulders as I devoured her words on the balcony wearing white gloves, so as not to mar the stiff, yellowed pages.

The novel begins with a man’s reply to his female lover’s letter:

It’s true, I didn’t come. I never intended to.

And I can’t accept the discreet excuse you offered me in your letter.

I don’t believe you waited long enough for me . . . I asked for you to wait as a period of gestation during which your desires would consolidate, your emotions coagulate. Until now any man has been able to satisfy these desires in you, but after this waiting period, they will be devoted only to Man.

Because waiting shapes his story and gives him his reality . . .

Like hunger, waiting is creative. It rouses new senses and needs, and so it offers Man an infinitesimal keyboard and a palette with metaphysical resonance.

Waiting entices the desired man, and he comes more quickly when he is late than when he is on time.

It is tempting to make a case for Rut Hillarp as Sweden’s Anaïs Nin. In response to Anaïs Nin’s notoriety, she wondered in a 1951 letter if she too couldn’t do just as well. Indeed, they have a similar erotic project. Like Anaïs Nin, Rut Hillarp’s works trace a map of the psyche’s movements through love, lust, and desire. One could align elements of Hillarp’s life (including a connection to Paris and creative intercourse with renowned cultural figures of her time) with Nin’s own. Whereas Nin’s fame was helped along by who published her in English and the censorship trials that added that tantalizing element of the forbidden to her work and life, Birgitta Holm offers no comparable story of scandal in her 2011 biography Rut Hillarp: Poet och Erotiskt Geni. Hillarp was a celebrated writer who traveled the world, took the matter of having lovers and being a lover seriously, and for whom desire was a way of becoming more receptive to her environment. One could try to spin sensation from the threads of her life—her joy in photos from costume parties, the cancer that left her with only one breast, the men and women who she invited to stay at her home, her masochism, her suicide—but that would do a disservice to a heart that beats with a singular rhythm. Holm, her former student and close friend, calls her an “erotic genius.”

Life Meets Art

Like other beloved eroticists, Hillarp’s life and art are intimately entwined. Rut Hillarp’s father was a hardware dealer and her mother was an evangelist in Sweden. And so religious mythology emerges as a major theme across her work. She draws from Norse, Greek and Biblical stories, and in each of her novels she wrestles with the idea of God and interrogates the logic of sin. For Hillarp, sex was sacrament and the erotic had the power to subsume the religious. “Even if you’re not aware of it, you know that intercourse is supposed to be a ritual act, a symbolic repetition of Creation. Not a bit of extra heat in bed and a quiver in your membranes,” Hillarp writes in her third novel En eld är havet (Fire Is a Sea, 1956).

Hillarp was one of few women in the inner circle of poets (mostly) who published in the literary journal 40-tal (The Forties) who were storming the Swedish literary landscape with their lyrical modernism, including Karl Vennberg, Eivor Burbeck, Solveig Johs, Gösta Oswald, Sivar Arnér, and Erik Lindegren. In 1946 she debuted as a poet with the collection Solens Brunn and would publish five more collections. In a documentary about Hillarp’s love of dancing and the dance halls in Paris (such as Olympia—whose other visitors included Marcel Marceau, Raymond Queneau, Juliette Greco and Grock the Clown—and other venues in which one risked one’s reputation simply by association), Holm says Hillarp distinguished herself further in this circle by “emphasizing her femininity erotically and socially.” Dancing, too was a recurring theme in her work, encompassing submission, masochism, freedom, and oblivion. Take this passage from The Black Curve:

But we danced and danced . . .

Danced every night until dusk. It snowed.

Dancing means giving up, disappearing, and that’s why all women want to dance. And you who didn’t exist, you have to dance the death of your women in order to experience them. Every night in the snow-dusk and cloud-dusk we danced and the dance was the softest death. The eagles of the day flew into the sinking sun.

And each step was destiny: entangling and enticing and gliding. Ever further into your kingdom, your crown of ice ever more irreproachable, ever more threatening. And I loved my fear: the murmuring seashell-song inside your affection. Murmuring its black curve.

From 1946 until 1963 (when she published her fourth novel Kustlinje [Coastline]), she published regularly with two of Sweden’s largest publishers, first Bonniers then Norstedts, and worked on experimental films that call to mind the work of Man Ray and Maya Deren. Her long career as a high school English, Swedish, and German teacher began in 1945. In 1982, she made a comeback with her collections of poetry and photography, the first of which was Spegel under jorden (Mirror Under the Earth).

When she published Strand för Isolde (A Beach for Isolde) at seventy-seven years old in 1991, Hillarp’s career as a writer found a new life. She was reappraised by critics and now “belonged to the young,” as Holm writes. The pop group Änglagård put her poems to music. She was asked to design a number of album covers, young feminists flocked to her, and in 2001 she exhibited at the Nationalgalleriet in Stockholm. When she performed her poetry—at the age of eighty-six—to a large audience at the 2000 Arvika music festival, she was considered a highlight of the event. Ever alive to the culture of the day, Hillarp told journalist Johan Wingestad that she was looking forward to seeing Einstürzende Neubauten perform; she had several of their albums at home.

Then, in 2003, Rut Hillarp committed suicide. In the midst of a discussion of Hillarp’s erotic masochism and “autopossession” (being able to hold your own reins) in Birgitta Holm’s biography, Holm writes with wrenching suddenness, as if it were an aside: “With a plastic bag over her head, taped tightly, I found Rut one November day in 2003 when I cycled out to [her home in] Årsta.”

Blood Eclipse

As a young woman in Stockholm during and after the Second World War, Hillarp frequented expat haunts, notably Rive Gauche, a bar where intellectual refugees from across Europe congregated. Among them were the Belgian poet and artist Olivier Herdiès, the Estonian poet Ilmar Laaban, and the Berlin-born writer, painter, and filmmaker Peter Weiss. And Mihail Gandhi Livada: a Rumanian poet, engineer, and composer (among other things). Hillarp and Livada’s love affair was the inspiration for Blood Eclipse.

Blood Eclipse is a “surrealized autobiography”—a story of a love affair—that explores the origin of romance through dreamlike prose poems, scenes adapted from Hillarp’s diary, a dialectical dialogue between two lovers (Man and Woman), and Woman’s inner monologues on sado-masochism, love, power, gender and desire. Her prose is lyrical and full of longing: for passion, for intelligent sadism, for recognition and understanding. For freedom in a man’s world.

She was married at the time she wrote Blood Eclipse, but kept lovers. In Fire Is a Sea, we are perhaps given a glimpse into her reasoning. She writes that committed relationships begin to take on the whiff of “incest,” so couples must either develop a taste for this dynamic or keep the passion alive by seeking fire elsewhere, and that heat keeps the couple’s relationship alive. In Blood Eclipse, this dynamic is teased out and presented as a sophisticated sado-masochistic power play with rules and expectations that both enliven the woman and cause her distress. Woman is an erotic masochist, but Man, more often than not, seems simply uncaring, unfeeling and as such, sadistic only for sadism’s sake, not hers. The lovers in her novels are often not as invested as the woman, or perhaps do not understand the framework of the desired erotic play (or perhaps are bad at playing?), and this dynamic is tragic. One feels great empathy for a woman who wants to find a erotic partner, but the mores of the time, ego, and perhaps simple miscommunication prevent her from finding a balanced bond.

Soon before she wrote the diary entries that informed Blood Eclipse, Hillarp had ended a relationship with the Englishman Louis Wilkinson, a lecturer, author, and biographer of John Powys. Holm writes that their relationship ended because Wilkinson couldn’t fulfill the role she needed of him; he treated masochism as a game, rather than embracing it fully and arresting her body and mind. The man who did engage her masochism was M. G. Livada, though he does not come across well in Blood Eclipse. In real life, he was nicknamed “The Crow”. And so, when a critic expressed such a low opinion of Livada’s character in the book, Hillarp sighed and wrote in her diary: “Poor Crow!” In that same diary (which she wrote in the third person, switching effortlessly between Swedish and her other languages), she recounts in English and French how one of her lovers, a Frenchman called Léon who presumably was part of the Rive Gauche crowd, had described his impressions of Livada to her:

— He is a Roumanian — What does that mean? — They are ideal lovers. Oriental. Adoring women, falling on their knees to them, clinging to them. Like Italians. You don’t know about Italians either? What do you know of love then? — Have you known him long? — As long as he has been here. But we never talked of anything but women. I can meet him in the street and say I have had a phantastic woman, making love comme une française, and the eyes bulge out of him, he takes out his note-book and writes everything down, her specialities, her tel-nr. And next time I see him, he can say “Elle n’a pas voulu”, and I have forgotten her long ago. — Il est trop empressé? Empressé? Vous comprenez? — Oui, she laughed.

A number of scenes in The Black Curve seem to have been drawn directly from her diaries: dance halls they visited, broken bike lights, summer in Stockholm’s archipelago. Take for instance this diary entry, which she originally wrote in English and French, and the following extract from The Black Curve. Images, snatches of dialogue, cruelty and tenderness echo in the translated extract. With its reference to seeing “my morning”, the second extract also touches on an idea about duality that recurs throughout her work: there is a different self for day and night, the former is sensible and matter-of-fact and the latter, free and sensual. I imagine her language comes from night.

From her diary (in her own English):

She remembered his face in the dim light, a new face, still with beauty, youth, a strange face, stirring her soul, and through her soul her body. She remembered him standing at her head, opening the blind to let in the pale sky on her; his voice as if a miracle had happened. “Mais tu es terrible comme amante. Tu me fais peur. Why haven’t you told me? Tu ne fais pas de réclame!” She remembered him hiding his happiness in self-irony, on his way out, giving her a cigarette from a packet he caught sight of when opening his bag to put in the belt they had taken out of his trousers. “Others would have offered you their lives and their fortunes for such a night, and I offer you a cigarette!”

From The Black Curve (in my translation):

I smoke too much now. “Others would’ve given their lives and all their earthly possessions for a night like this, and all I give you are a couple of cigarettes,” he said. I didn’t know there were only two left in the etui. If not for her, they would’ve just laid there — idiotic souvenirs — I wasn’t available that night anyway. His voice a wonder. “But you’re ... You frighten me.” He stood by the bed, pulled the curtain aside so he could see my morning. And his face, renewed, distant, resting in its own myth. It doesn’t speak to me anymore.

Hillarp’s love affair with Livada was one of creative intercourse as well. He read her work, offered notes, and according to Holm, Hillarp can be credited with giving direction to his scattered set of talents. At one point, Livada wrote (in a mix of English and Swedish) to Hillarp about the diary entries covering their relationship, and which would later make up passages of Blood Eclipse: “What a novel! Teaching people to love and understand love. The first real analysis of love from all points of view. Not even Proust was better, he was too ill.”

As a reader, Hillarp’s language swallowed me, an experience not unlike being caught in a shorebreak wave. As a translator, her prose made me feel afloat. I sat down with Malte Persson, a young Swedish writer whose playfulness and modernism I admire, to puzzle out certain turns of phrase and images. Wherever I was struggling to find something concrete—a link to an idiom, perhaps a play on words—we rarely settled on a reading that leaned this way or that. The general conclusion of our long meeting was that the text was meant to be read freely. We wondered how different the book would have been had she not self-published. This refusal of fixed meaning, however, aligns with the aesthetics of the time. Anxiety and disillusionment characterized the work of the Forties-writers writing in response to the political climate in Europe, as well as with an awareness of the world around and its shortcomings. These writers distanced themselves from the conventions of language and welcomed ambiguity. Or as harsher critics put it: incomprehensibility. Take for example this moment in The Black Curve:

Too many keys too many doors. The front door that always was, the windows, the blinds. Everything happens in other rooms. And yet only I live in the house no one else knows where it is where is my house is it on the cliff by the sea where the horizon, was there once a horizon and my blood that drowned the horizon our silence that drowned my blood your pulse against my lips the morning you stayed that morning.

Hillarp’s prose asks for a physical response, but not in the way of horror, comedy, melodrama, or pornography, genres whose highest praise is the unleashing of our fluids and convulsions. With varying degrees of conventional and experimental storytelling, her novels ask you to let go of the attachment to meaning. Hillarp asks us to transcend the flesh and feel: “God is an experience: it feels like something supernatural. God is the experience from which love springs. In the moment of feeling, one doesn’t doubt,” she insisted in Fire Is a Sea.

I find myself quoting from this novel of ideas often in this essay. In part, I assume, because it lends itself to quotation particularly well. More conventional in form and narrative than her other works, it has the quality of a parable, telling the story of two types of women (Charlotte: free with herself and her body; Rakel: weighed down by an evangelical childhood; both burdened by their place in a patriarchal society, which can be read through the male characters). In it, we also encounter an “erotic high priestess” called Cynthia (who we assume is the eponymous Sindhia from her second novel). Cynthia muses on love, God and the erotic with Charlotte. Though Hillarp’s diatribes against the patriarchy in Fire are sometimes jarring and as subtle as bricks, when I consider her body of work as a whole, I find myself cheering Hillarp on in these moments.

In Eclipse, we are introduced to the themes and style that she carried through each of her novels. In a scene where Woman is graphing her experiences with Man, she shares her findings with him. The black curve is pleasure. The red is jouissance. And violet, which she introduces later, is man’s domain: the power he has in guiding the black curve.

He asks: “What are you painting?” and she replies:

Love. The towers and the valley of dreams. Charting curves that aren’t found in books. This one here shows what it’s like when I’ve waited a few days: it shoots straight up for ten minutes, followed by waves with increasing distance between the peaks, and peak- ing in different ways. Meanwhile, the red curve is climbing steadily, that’s happiness; the black is pleasure, and as you can see, it reaches its climax later, it can take a few minutes, and then it stays up.

—For how long?

—It depends on how ravenous you are and how long you’ve been at it. An hour, half a day. Or until the next time you become cruel.

In this examination of a female masochist and her cruel, calculating lover, gender dynamics are laid bare and we are given insight into the nature of female (her) masochism. How easily the expectations of women in society and their lack of power and agency can cloud pure erotic play. In this story, Man creates love out of the material of the Woman. He wants nothing from her but for her to be the material to play his love off of. In Blood Eclispe and beyond, masochism, as Aase Berg, the poet and critic who once studied under Hillarp, writes “is a strategy of achieving control over suffering—by seeking out that which one fears the most. The ritualized suffering differs from the uncontrolled and chaotic in that it is ‘self-determined.’” In this Promethean way, Hillarp takes fate into her own hands. Berg continues: “In that the feared quality is the capricious nature of suffering, the masochist is invulnerable.” At the end of the novel, Woman discovers Man’s laboratory, which is filled with his other women. It’s a Cronenbergian horror-show.

One couldn’t stop combing her hair, she had very long and beautiful hair that even grew from her shoulders. Another was reading old letters, holding them upside down. On a third, her arm and leg had been switched, so she could not walk and was forced to cartwheel around. There were women dripping wax on their arms and women playing with themselves.

In the end, Woman finds herself stripped of any agency she thought she had in the affair when she discovers that she is nothing more than matter in his grand love experiment.

Hillarp submitted Blood Eclipse to Bonnier, the publishers of her poetry, who then requested a number of changes she wasn’t willing to make at the time. The arts journalist Gunilla Kindstrand suggested the book was too experimental and outspoken for its time. Eventually Hillarp decided to self-publish, Holm writes, in part to clear the table so she could work on her second lyrical novel Sindhia (1954). Her debut was met with critical praise, and soon went into a second printing. Holm writes that female critics of the time felt the novel was groundbreaking; Hillarp was the first woman to put to words what women had been feeling about their erotic lives. In certain circles, the term “blood eclipse” became synonymous with twentieth century love.

The theme of female masochism is further developed in Sindhia, her prose masterpiece. Where Blood Eclipse’s experiments can seem obscure in form or meaning, Hillarp achieves a moving clarity in her formal play, surrealism, dialectic, and lyricism. The novel delves deeper into submission and the idea of men as gods. It was reissued as a print-on-demand classic by Podium in 2000 and in the preface Kindstrand writes:

Here we find depictions of questions that every age has tried to steer clear of, including the women’s movement: How do we reconcile equality with love’s demands of power and submission? Can passion and fellowship ever be reconciled? Is a perfect union even possible? . . . Sindhia has waited nearly half a century for us to be ready to listen. [Sindhia] knows that certain experiences don’t age.

Has her time finally come?

Sindhia is a dark and powerful novel that reads like dancing: leading and yielding, rich with controlled flourishes and subtext. In episodes in cafés in Paris and with lovers and friends, in letters to, from and about Sindhia and through shifting perspectives, we are given intimate access to the story of Sindhia and Reger, an indifferent man who learns that they had a love child, which she has given up for adoption. Sindhia is a high priestess of the erotic, and as in Hillarp’s other novels, no level of erotic religiosity can change the fact that women pay a higher price for their sexuality. We see Sindhia’s narcissism, her longing, how she is trapped and how she finds moments of freedom.

Amid further exploration of female eroticism and the dynamics needed for a fulfilling love affair, we are also drawn into an exploration of motherhood that would fit in with today’s discourse about a woman’s right have control over her own body.

She had made her decision, it was finished and all tied up. All she had to do was dissolve it, so that it wouldn’t sit inside her like a parcel, but become part of her flesh. Sometimes she thought of eating her child.

All she could do was wait. Ever more rarely did she become sentimental, hearing the voice that spoke that illogical feeling’s word: “son.”

Never did the voice say: “daughter.”

A son, a son—the word, the idea intoxicated her. But when she thought about a grabbling, whining creature with an unfamiliar face, the feelings didn’t follow.

Instead she thought of young men with beautiful child-like lips. There was one in particular, but he was far away. She wanted to stuff one of them in a bag, so that everything would be still, and nothing more would happen in this world.

“The bag.” A child in a bag. A madonna in a bag. Each time this image appears, I hear the echo of her suicide ringing with the desire for control and autonomy in a world that is not her own.

We find this idea distilled in Kustlinje (Coastline, 1963), her fourth and final novel, a short travelogue based on Hillarp’s own journey alone on the Dalmatian coast. It is my personal favorite because in it biography and literature merge in a new way, and reveal a sense of the woman that inspired such devotion in her students and friends: wild, vibrant and witty. We meet a woman at ease in middle age, alive as ever to the looks of longing around her. Nothing seems to be setting her desire ablaze as before, even though she is still interested: “How many seductions have happened to the tune of ‘Why not?’” Though her interest in the men around her is noncommittal, she still finds herself drawn in and her emotions batted about when she encounters their desires and expectations. Coastline begins:

Strange Seas

As a woman you are condemned to loving the strange. You wander on the shore of a softly sloping ocean floor, the sand gives under your feet, at play with each step. It’s summer’s inward caress and the beach is long long. But the water is rising. It fills in and levels out. You wander unknown. You wonder who you are — perhaps? Who you would be if you were wandering by a different sea?

A man in the distance entices, hands full of tenderness:

“Come! I’ll teach you how to swim.” Which means: “I’m going to help you drown.” But he doesn’t know that. Neither does he know how much you wish to drown.

Once there was a different sea, in the middle of the world.

Someday there will be a different sea!

This is man’s sea, strange and beloved. Surging oceanic, rising, filling my tracks and caves.

Most striking about this slim volume is the moment when she longs for female companionship, echoing a prominent feminist theme in recent pop culture and literature (Girls, #squadgoals, Rachel B. Glaser’s Paulina and Fran, Sheila Heti’s How Should a Person Be?, and so on). In this man’s world, she seems to be saying, it’s easier to have relationship with the opposite sex than it is to solicit female friendship (which can perhaps be extended to solidarity). She writes:

All the waiters greet me when they pass by. Why are there no waitresses in this country? Behind me and to one side is a woman who I’d very much like to speak with about many things. She looks like Birgit Cullberg, but with black hair, and works in town: I’ve seen her on my way home, stopping in for a cup of coffee at a little café near Placan, taking a seat among the men at the regular’s table in the center. That was when it was rainy, we looked at each other, her face sparkling with laughter, her eyes half-moons. She attended the first concert wearing a white jacket, and now she’s sitting among friends again. If one of us were a man, we could have danced and gotten acquainted that way. But that could also have led to the silly troubles that gender creates. That one partner will want to dig their claws into the other. Wanting more. And more. Speaking in a tense made with the help of infinitives: future. And tomorrow, domani, dopodomani.

In Coastline, Hillarp’s examination of the alienation inherent between men and women. She writes using the kind of language you use when you do not share a common tongue: snatches of other European languages and gestures filling in where mother tongues and common tongues fail. With a sense of humor and exasperation, her characters make themselves understood to each other and she to us, and meaning takes shape between the lines.

In this observation of the other woman is an echo of a question she asks in her debut novel, too. Framed by her admiration of women, Hillarp’s female protagonist stops to ask an important question, one that asks to know the other side of the stories she has been telling. It goes like this:

One should love women. Not young girls, they are tedious, but women of my kind, shutting their lips in dreams of my own pain, the proud curve of their betrayed necks in my hand. Women with forest-eyes, ocean-eyes. Women with the downy caress of hair on their anxious shoulders. Women who say inappropriate things at gatherings. Women of great suddenness and silence, whose nights turn me into one. Women with bodies of longing.

What have men done with their own bodies?

With this question, Hillarp also seems to be asking us to think of ourselves as both subject and object of our perception—to put ourselves in the picture when we look at the world, so to speak—to interrogate how the way we look at the world, affects how we understand ourselves. It reads as an acknowledgement that her female story, voice and gaze can only go so far. The recipient of the gaze has to respond, and through call and response, perhaps “Someday there will be a different sea!” This call echoes in the space between emotion and language, public and private, me and you. Like the idea of Hillarp herself: intimate and unknowable, enduring but caught in the folds of history. Rut Hillarp—a great and enduring talent obscured by the folds of history—invites us into this space and asks us to listen.

Saskia Vogel is a writer and translator from Swedish. A native of Los Angeles, she now lives in Berlin. @saskiavogel

Biographical information comes from Birgitta Holm’s Rut Hillarp: Poet och Erotiskt Geni (Atlantis 2011) and Dagboken by Rut Hillarp (selected by Birgitta Holm, Atlantis 2011), unless cited otherwise.

The Black Curve by Rut Hillarp is published by Readux Books. It is a long standalone extract taken from the novel Blodförmörkelse (Blood Eclipse).