Linor Goralik (credit Olga Pavolga)

Russian-Israeli writer, poet, playwright, and installation artist Linor Goralik first entered the literary scene around 2001 as a prolific LiveJournal poster. A workaholic founder of new-media discourses, she soon became a fixture of the early Russian-language Internet. Perhaps because it originated in the blogosphere, Goralik’s writing often seems aimed at a narrow circle of insiders—an impression fostered by the remarkable intimacy of her style and her excellent eye for detail. This last quality enables Goralik to be political without veering into preachiness or polemic. For example, her ongoing “Five stories about…” series presents topical vignettes from the life of Russia’s liberal intelligentsia that, at first glance, seem entirely divorced from politics. Identified only by their white-collar professions and a single initial, Goralik’s characters are shown simply moving through life: going through passport control, dealing with a mole infestation at the dacha, or declining a favorite nephew’s request to photograph his upcoming orgy. For all their understated irony, these little fables often end with a devastating twist. Each one begins with a mock-hypothetical “So, let’s say…” followed by an anecdote of such lapidary specificity that it seems drawn from directly observed reality. One entry from April 2014 reads:

So, let’s say classics professor S. tells her students that, when considering the culture of the Roman Empire, it’s important to note how small the number of truly educated people really was. And that the entire intellectual elite of Caesar’s time could have fit into two to three paddy wagons.

What is this story about? The words “let’s say” recall the beginning of a mathematical proof, suggesting we’re about to witness the impartial demonstration of a general principle. The next line only intensifies this impression with its neutral invocations of the nearly nameless “classics professor” and the cultural values of ancient Rome. But the final sentence—specifically, the reference to “paddy wagons,” which police have been stuffing full of protesters since the “Snow Revolution” of 2011–12—makes it clear that S. can only be a Russian intellectual speaking to a group of like-minded peers. Slow-burn syllogisms like this one belie Goralik’s claim that she doesn’t “give a shit” about politics, as she told journalist Yulia Idlis in 2010.

Goralik’s “Bunnypuss and His Imaginary Friends: F., Sch., Hot Water Bottle, and Pork Steak with Peas.”

Left-hand panel: To make Neapolitan sauce, all you need are some nice, inexpensive little tomatoes.

Right-hand panel: To get nice, inexpensive little tomatoes, all you need is regime change.

Much of Goralik’s work, including the pieces below, relies on this kind of reversal. After carefully constructing the illusion of sober abstraction, she tops it with a detail that brings the entire structure tumbling down to earth. Sometimes this detail acts as a punchline (as in the cartoon, here, from the Bunnypuss strip); at other times, it is more like a Chekhovian pointe, requiring several lines, paragraphs, or pages to emerge. Even as Goralik addresses topics specific to the contemporary Russian context, such as the effects of Western sanctions or the lingering traumas of Stalinism, she also pushes universal emotional buttons. Sudden sartorial upsets, a snub from a colleague, a misinterpreted remark: Goralik excels in wresting these small moments from a sea of higher-profile troubles.

Just as we can discern the ancestors of the novel—the letter and the diary—in eighteenth-century exemplars of the genre, so too does Goralik’s writing betray its roots in the anarchic, confessional culture of early Runet. Even on paper, Goralik’s texts retain an intimacy and immediacy, a sense of just having been overheard, that digital natives associate with online posting. They are also eminently shareable, which is what compelled me to translate them in the first place—so I could keep on laughing and cringing, this time with English-speaking friends.

—Maya Vinokour

EVERYTHING IS FINE

From the cycle “In Short: Ninety-One Rather Short Stories”

Translated by Maya Vinokour

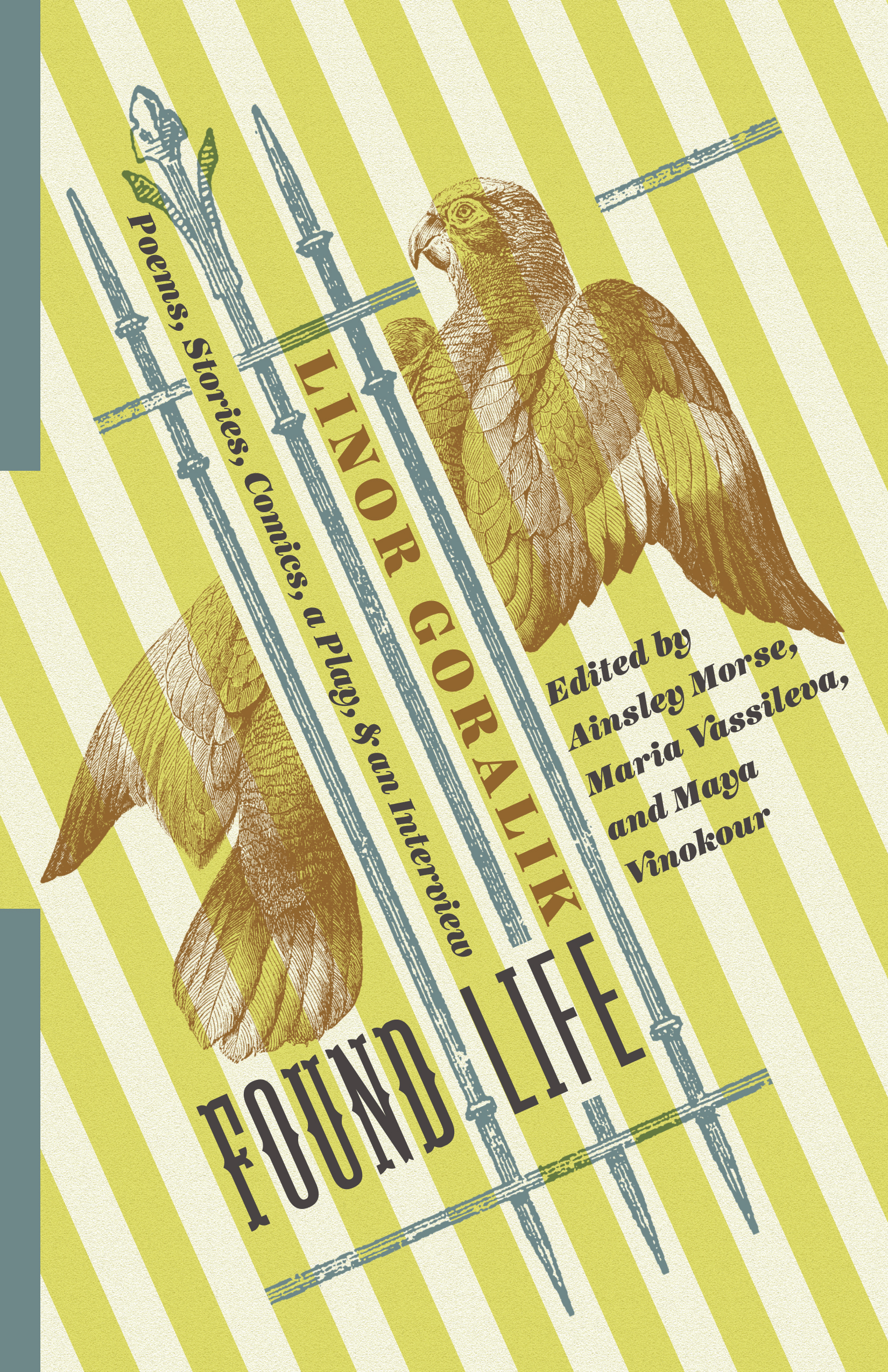

Found Life: Poems, Stories, Comics, a Play, & an Interview

by Linor Goralik

(Columbia University Press 2017)

Not only was the ice cream the best ice cream in the world, but also the weather was the best weather in the world, and the pebbles they found were the roundest, pebbliest, weightiest pebbles in the world, and Tima didn’t keep straining his harness, but behaved really well, and Yonka secretly fed him a scoop of ice cream, which Tima was absolutely in no way allowed to have, and he ended up all smeared in it, and Marinka guessed everything, and told on her brother to Mom and Aleksei, and Yonka would have certainly gotten it in a big way if this had not been the best day in the world. They had been planning this day for almost a month, Aleksei kept trying to convince her, and she would initially yield, then say, “No,” and he never argued, would just say, “OK, no means no,” and she would think each time that if he hadn’t been so laid back, she would never have gotten to know him in the first place, if even once during these past five months he had tried to pressure her, hurry her, push her, she would never have agreed that time even just to have tea with him in the hospital cafeteria. He had walked up to her when she was standing in the middle of an empty parking lot, in the hellish sun, just standing there, not knowing how to go on living, and said, “I’m Aleksei, I work here, I’m a physical therapist. There’s a cafeteria, would you like some tea?” And she said, “No,” and he said, “Sorry,” and started walking back toward the hospital, and then she said, “OK, let’s go.” And when he said that they should finally spend a day off all together, really together, with the kids and Tima, she had said, “No,” and continued to say “No,” “No,” “No”—when he suggested not going to Izmailovo, but just coming out to a little park on Pokrovsky Boulevard, when he said that they shouldn’t eat in a café but take food with them so as not to risk it with Yonka’s mysterious new allergy—she would say, “No,” he would say, “Sure, OK,” and then bring by a map of the park, or tell her about the weekend weather report, or appear out of nowhere with a dusty picnic basket, put it on the balcony and explain to Marinka where things go (“forks on the left, knives on the right, like in the picture, see?”). So when he said that they should take Tima along, she, of course, said “No,” and he acquiesced and didn’t say anything for a couple of days, but then brought a wide harness with a clasp on the back for Tima. This was so barefaced it actually took her breath away, and she threw the harness at him, the clasp hit him in the ear, he clutched at it, and then calmly picked up the harness and put it away, not in his backpack, but in the hallway closet. And, of course, they took Tima with them, and he behaved himself really well, strode confidently up ahead on the wide short leash, and then, when she took his container of food out of the basket, Tima suddenly looked at her with totally clear eyes and embraced Yonka with a steady, robust motion, a motion as accurate as if there had never been any stroke.

FOUR EXCERPTS

From the cycle “She Said, He Said”

Translated by Ainsley Morse and Maya Vinokour

. . . he’s styling my bangs and talking away as he goes—and he’s this glamorous young man, a real stylist—so he’s prattling on about all sorts of well-bred trivialities entirely appropriate to our discourse, like how young Sofia Rotaru looks. And suddenly he says: “By the by, I grew up with foster parents. My real parents worked a lot and put an ad in the paper: for someone to pick up the kids from school, and we’ll take them on the weekends. One elderly couple responded,” he said, “their thirty-year-old son had just drowned. They were very unusual people. The granddad had lost one arm in the war, but before that he’d dug canals and been in the camps and everything. I don’t really remember much about him. I do remember, he always used to tell me, he had this hoarse voice: ‘Eeegor, if anyone esks you what time is it—ponch ’im upside the chin.’ But why, I don’t know,” he says. And then more blah-blah, blah-blah about bronze highlights in dark blonde hair. I asked him cautiously: “Igor, it was probably his left arm he lost?” “Yes,” said my hairdresser, astonished. “In that case,” I say, “it probably makes sense why he would tell you about people asking the time.” “What do you mean?” said my hairdresser. “Well,” I say, “just think about it—If someone wanted to make a cruel joke . . .” He looked at me silently in the mirror, then lowered the blow dryer and was like: “Oh wow.” Then he turns the blow dryer back on, then puts it down on the little table, walks off and sits down on a stool. “Just give me a second,” he says. “I have to think about this.”

. . . everyone hates us, but it’s not like we’re having a great time. Like, on New Year’s the boys call me up: lieutenant, sir, they say, there’s a guy climbing the Christmas tree here. You know, near Lubyanka, on that street, Nikolskaya. He’s climbing right up like a monkey. And it’s a holiday. And I think: so now I tell them to take him down and bring him in, and it’ll just be one more police asshole sticking it to someone, on New Year’s to boot. So I’m like: “Is he climbing kinda calmly?” They say, “Yeah, pretty calmly, just climbing along.” “Then screw him,” I say, “let him climb.” The boys don’t care, it’s a holiday for them too, they want to do like everybody else. So I’m sitting there thinking: I did a good deed, like they say—how you start off the year and all. So I’ll have a good year. Then fifteen minutes later they call again. He crashed down out of that tree and broke his neck. Soon as they got to him he’d already broken it. There’s your good start. And you tell me everyone hates us! Why don’t you climb on down here with your ID ready, don’t fuck with me, you smartass!

. . . every Christmas people set up those little scenes from the life of, you know, Jesus, little cradles and all that. So he bought like five pounds of meat and went around his neighborhood that night and switched out all the Jesuses with, like, hams . . . It was super conceptual, really great. Not like just sitting at home with the family, smiling like dumbasses.

. . . taught myself, so my brain just turns off at moments like that. I’m a robot. I could tell a block away from the smell that it was fucked over there. I was right—there was nothing left of the café, just a single wall. That’s when I just flip the switch in my head: tick-tack. I’m a robot, I’m a robot. Then for three hours we, you know. We generally break up into groups of three, two do the collecting and one closes up the bags, so there I am zipping—zhzhik, and it’s like these weren’t people, we’re just collecting various objects and putting them in sacks. We were in four groups, finished in three hours. Zvi says to me: let’s do one last walk-through, just in case. Sure, what do I care—I’m a robot. We walk around, look in the corners, the wreckage, where we can we rummage around a little. Looks like we got everything. And then I notice, like out of the corner of my eye, some kind of movement. And I’m like: “What’s that?” I look, and by the one wall that didn’t collapse, there’s a display case, still in one piece, and there’s pastries in it, rotating. And that’s when I threw up.

Linor Goralik is a Russian-language writer, journalist, and cultural critic. She has published prose, poetry, flash fiction, plays, children’s books, a science-fiction novel (2004, co-authored with Sergei Kuznetsov), and a monograph on Barbie (2006).

Maya Vinokour is Faculty Fellow in the Department of Russian and Slavic Studies at New York University, specializing in late-Imperial Russian, Soviet, and post-Soviet literature and media.

All excerpts from Found Life: Poems, Stories, Comics, a Play, & an Interview by Linor Goralik. Edited by Ainsley Morse, Maria Vassileva, and Maya Vinokour. Translation © 2018 Ainsley Morse, Maria Vassileva, and Maya Vinokour. Used by arrangement with Columbia University Press. All rights reserved.