Fifty years ago this month, on July 17, 1967, saxophonist John Coltrane died of liver cancer at Huntington Hospital in Huntington, New York. He was forty years old. Coltrane was arguably the central figure of the rapidly evolving New York jazz scene, and his death came as a shock to the musical community. Trumpeter Miles Davis, one of Coltrane’s former bandleaders, said, "Coltrane's death… took everyone by surprise. I knew he hadn't looked too good... But I didn't know he was that sick—or even sick at all.” Coltrane’s funeral would be held four days later at St. Peter’s Lutheran Church on Lexington Avenue and 54th street in Manhattan. St. Peter’s was an ideal setting for the funeral, as under the leadership of pastor John Garcia Gensel, the church had embraced New York’s diverse jazz community through a “jazz ministry” founded in 1964 (a commitment that has continued into the present day). Reporters estimated that nearly one thousand people filled the church for the service, including a who’s who of jazz musicians: Dizzy Gillespie, Max Roach, Gerry Mulligan, Archie Shepp, Milt Jackson, and Nina Simone, to name a few.

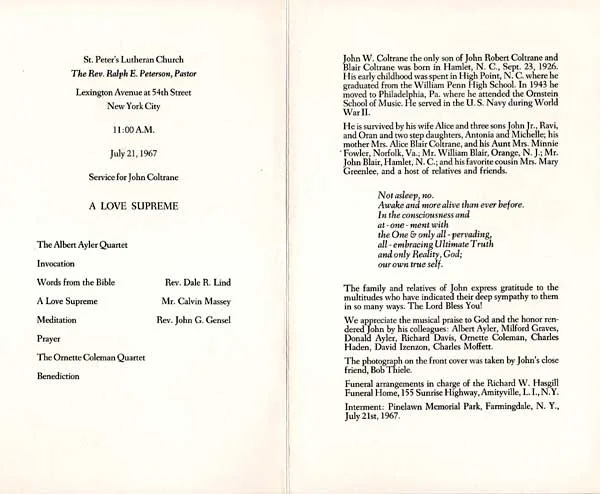

Program from the funeral of John Coltrane

The service featured readings, including Coltrane’s friend, the trumpeter Calvin Massey, reciting the former’s poem “A Love Supreme”, and musical performances by Coltrane’s saxophonist-peers Albert Ayler and Ornette Coleman. Ayler’s quartet, featuring Donald Ayler on trumpet, Richard Davis on bass, and Milford Graves on drums, opened the ceremony, while Coleman’s quartet, featuring David Izenson and Charlie Haden on bass, and Charles Moffett on drums, played just before the benediction. Both of these incendiary performances were captured on portable recording equipment—albeit with fairly low fidelity—and were eventually released on record. (Ayler’s performance can be found on the compilation Holy Ghost: Rare & Unissued Recordings (1962-1970), released by Revenant Records in 2004, while Coleman’s performance was originally released under the title “Holiday for a Graveyard”, on the album Head Start by the Bob Thiele Emergency on Flying Dutchman Records in 1969.)

Befitting his overarching influence on the direction of jazz in the 1960s, Coltrane’s funeral was the largest public memorial service for a jazz musician to date. (While Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington would receive even larger public displays of mourning, they lived until 1971 and 1974, respectively.) The range of musicians who came to the service was evidence of the outsized role Coltrane had played in shaping several strains of modern jazz—post-bop (as on his 1959 album Giant Steps), modal jazz (as on 1961’s My Favorite Things and 1965’s A Love Supreme), and free jazz (on his later albums, like 1966’s Ascension). His influence could be heard in players from across the stylistic spectrum, and he was still in the prime of his career. Egged on by Coltrane’s inveterate search for new ways of playing, jazz was quickly becoming an accepted form of art and experimental music. How could one properly and publicly memorialize such a central figure in the jazz world—a task with very few prior antecedents?

Because of Coltrane’s musical stature and the public nature of his funeral, the performances by Albert Ayler and Ornette Coleman had the power to establish the conventions of a modern jazz requiem—how to properly memorialize a member of the jazz community. In their performances, Ayler and Coleman memorialized Coltrane not through imitation or pale attempts at resurrection, but by organically integrating aspects of Coltrane’s playing into their own distinct styles—a form of musical signifyin(g).

***

After Coltrane, Ornette Coleman and Albert Ayler were easily the two most talked-about saxophonists of jazz’s avant-garde. When Coleman brought his quartet to the Five Spot club in the East Village for a two-week residency in November 1959, he turned the jazz world on its head. While Coleman’s tunes had roots in the blues and bebop, the improvisational structures were much looser, sometimes bordering on the non-existent. Coleman himself was less concerned with harmonically complex lines in the vein of Charlie Parker than with playing with as vocal a tone quality as he could. While Coleman’s approach provoked sharp divisions within the New York jazz community, Coltrane was intrigued by it. In a 1963 interview, Coltrane noted:

I feel indebted to [Coleman], myself. Because actually, when he came along, I was so far in this thing [the "harmonic structures"], I didn't know where I was going to go next. And, I didn't know if I would have thought about just abandoning the chord system or not. I probably wouldn't have thought of that at all. And he came along doing it, and I heard it, I said, "Well, that—that must be the answer."

In 1960, under the Atlantic Records imprint, Coltrane recorded a series of Coleman tunes with the members of Coleman’s working quartet—Don Cherry on trumpet, Charlie Haden on bass, and Ed Blackwell on drums—though the recordings wouldn’t be released until 1966.

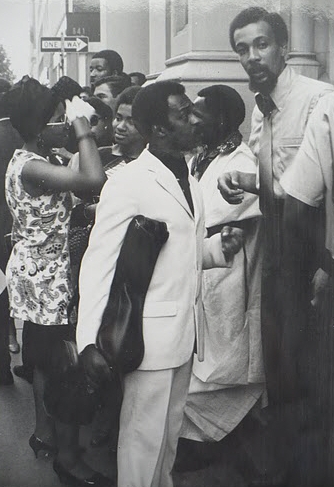

Albert Ayler & Milford Graves at the funeral of John Coltrane

Ayler was several years younger than Coleman and made a splash in New York in 1963, playing alongside pianist Cecil Taylor. Ayler had a big, burly sound evocative of bluesy swing-era players like Coleman Hawkins, but with the intensity turned up to eleven. For some, his broad vibrato went beyond the confines of good taste into buzz saw territory. He was interested in simple, hummable melodies, but would stretch them to their breaking point, rarely playing against a solid, swinging beat. With this controversial approach to music, Ayler had a difficult time finding opportunities to perform and record. However, his music caught Coltrane’s ear, and Coltrane would become Ayler’s most prominent artistic supporter, helping him secure a recording contract with his label, Impulse! Ayler would in turn influence Coltrane’s later moves toward free improvisation, and his consequent emphasis on tone quality over melodic syntax.

While Ayler and Coleman were both associated with Coltrane in the larger jazz scene, they never recorded with him. In addition, despite both players’ influence on Coltrane, it would be a misnomer to say that their styles and approaches truly resembled each other. In terms of creating the form of a proper jazz requiem, it is telling that the musical performances were offered by fellow musicians with their own strong personalities, rather than Coltrane’s own closest collaborators—pianists McCoy Tyner and Alice Coltrane; bassist Jimmy Garrison; drummers Elvin Jones and Rasheed Ali; saxophonists Pharaoh Sanders and Archie Shepp. Ayler and Coleman did not even play Coltrane’s tunes, instead offering either original compositions or free improvisations. It is clear that Ayler and Coleman were after a new form of memorialization that would not freeze Coltrane’s memory in stone, but that interacted with Coltrane’s legacy as a still-living agent.

***

Within each of their performances, Ayler and Coleman play as if Coltrane is in the band as well, offering his own improvisational commentary on the music. In other words, elements more commonly associated with Coltrane’s style actually inflect Ayler’s and Coleman’s melodic lines.

Albert Ayler, Don Ayler, & Richard Davis at the funeral of John Coltrane

To open the service, Ayler played a short medley of three original tunes. The first—“Love Cry”—was a relatively new tune that Ayler would record later that summer for Impulse! The next two, “Truth is Marching In” and “Our Prayer” (the latter composed by his trumpet-playing brother Donald), were standards in the Ayler repertoire. Both had been recorded live at the Village Vanguard that previous December and released by Impulse! earlier in 1967. (Coltrane was in the audience for this concert.) “Love Cry” consists of a somber, searching melody in B-flat major over a bass drone and frenetic cymbal textures. The melodic contours are reminiscent of a spiritual, or a Muslim call to prayer. “Truth is Marching In” is more hymn-like in its contours and harmonies, a messy chorale in D-major at a dirge tempo. “Our Prayer” has the same key and hymn-like feel as “Truth is Marching In,” but features fewer melodic notes held for longer periods of time, creating more space for Ayler to comment on the melody.

After “Our Prayer,” Ayler moves back to playing melodic material in B-flat major, very much in the vein of the “Love Cry” melody. Over this line, Albert begins to scream-sing, sometimes hitting discernible notes, other times unleashing more complex noise. Ayler’s vocalizations simultaneously evoke both terror and joy, inspiring the rest of the band to improvise at fever pitch. Ayler then brings the saxophone back to his mouth and cues the band to fade with a plaintive melodic resolution, an “Amen.”

Since the medley’s latter two tunes were recorded the previous December, we can compare the respective performances in order to reconstruct Ayler’s conception of the jazz requiem. In the earlier versions of both pieces, Ayler’s playing is dense and highly energetic. His lines are less rooted than in his funeral performance, jumping across the register of his horn. His phrases are more clipped, emphasizing harsh articulations rather than the quality of sustained tones. Motivically, Ayler focuses on little cambiata-like figures that ornament and circle a central note. These aspects are quite indicative of Ayler’s style, reflecting his desire to explore extreme timbral contrasts.

On the other hand, in his funeral performance, Ayler’s lines have a strong sense of directionality. Instead of jumping quickly between different ranges, he constructs lines that move up and down, stepwise, slowing as they reach their crest. The pointillistic quality of his typical improvisations is replaced with a new linear quality—a quality more associated with Coltrane’s improvisational style. Even as Coltrane moved from a dense, post-bop-oriented harmonic language to a looser and eventually completely open one, his melodic sense still retained its linear, bop-like character. This gave his music a searching quality that underscored the themes of spiritual pursuit present in much of his later music. While Ayler does not play phrases in his funeral performance that would be mistaken for Coltrane’s—they aren’t nearly as dense and traditionally virtuosic—the notable linear qualities of his improvisation show Ayler integrating the feel and character of Coltrane’s music into his own style, performing as if he hears Coltrane playing along with him.

Billy Higgins & Ornette Coleman at the funeral of John Coltrane

While Ayler’s funeral performance drew from traditional religious musical forms to create a meditative atmosphere, Coleman’s freely improvised performance was bluesy and hard-swinging. But like Ayler, Coleman plays as if Coltrane has his ear. Initially, the performance is classic Coleman, featuring his clear sense of melody and reedy, imploring tone. However, at about the 40-second mark, Coleman begins to play a series of dense streams of notes, quickly moving up and down the horn’s register. These sheets of sound are much more typical of Giant Steps-era Coltrane than Coleman’s vocal-oriented style. About two minutes later, Coleman unleashes a phrase that single-mindedly develops a short melodic motive, moving the starting note and metric placement of the motive around, but retaining its original contour. This kind of improvisational technique is also more commonly associated with Coltrane—perhaps the most famous example being his extended solo on “Acknowledgement,” the first track of A Love Supreme, and which slowly and methodically builds off of a three-note melodic cell. But as with Ayler’s performance, these nods to Coltrane’s style are subtle and fleeting, organically integrated into Coleman’s passionate solo.

***

The ways in which Ayler and Coleman obliquely reference and evoke John Coltrane’s musical style, without becoming subservient to it, can be conceived of as a two-way conversation between the living and the legacy of the deceased—a form of virtual signifyin(g). As Henry Louis Gates, Jr. describes in it his seminal book The Signifying Monkey, “signifyin(g)” is an African-American rhetorical trope that plays the semantic meaning and spoken inflection of words off each other for a particular effect. A classic example is the use of a negative word with a positive inflection, as a kind of compliment. That kind of interaction is deeply embedded in jazz performance and culture, particularly in the ways through which different musicians interact with each other, simultaneously trying to fit in with the other players while still articulating a unique personal voice.

Not only do the evocations of Coltrane’s musical style in Ayler’s and Coleman’s improvisations show these soloists commenting on Coltrane’s music; rather, they also show Coltrane “actively” commenting back on them. In Coleman’s performance, for instance, the way he introduces the sheets-of-sound idea and motivic development, seemingly out of nowhere, creates the sense that Coleman and Coltrane are playing together and feeding off each other. Both players are trading licks back and forth, constantly responding to and commenting on what has just been played. During the especially Coltrane-esque moments of Coleman’s improvisation, one can imagine him responding to a particularly potent Trane lick, attempting to fend off the musical barb and pull the group improvisation back toward more congenial blues-inflected territory.

John Coltrane

As a mode of mourning, the virtual signifyin(g) in the performances acts as a new, modern form of prosopopeia, a rhetorical device in which a someone speaks as someone else—as if the deceased person were communicating from beyond the grave. However, instead of pretending to speak as Coltrane, they perform as if speaking with him. This form of communing with the departed has the impact of distancing Coltrane’s music from that of Ayler and Coleman—by signifyin(g) with Coltrane, they show just how different his music is from theirs. Through their performances, Ayler and Coleman acknowledge their inability to recreate Coltrane’s unique improvisational style while still remembering and cherishing him through virtual musical interaction. In this way, Ayler and Coleman are able to memorialize the human Coltrane. Instead of reducing him to a repeatable, imitable riff, they preserve Coltrane’s spirit, a living legacy that continues to comment on new, creative music.

Ayler and Coleman’s virtual signifyin(g) simultaneously acknowledges Coltrane’s living presence in jazz music and their own inability to truly resurrect his musical personality. Jacques Derrida theorized this form of internally contradictory memorialization, arguing that the means of forgetting that are such a vital part of traditional mourning processes are unethical, and offensive to the lost loved one’s memory. For Derrida, the only way to truly honor the dead is to create a relationship that sustains a sense of intimacy while acknowledging the finality of death. This relationship, he says, takes the form of prosopopeia, a “fiction of an apostrophe to an absent, deceased or voiceless entity, which posits the possibility of the latter’s reply,” while still acknowledging that the other is “alone, outside, over there, in his death, outside of us.”

While Derrida’s ethics of mourning share a philosophical underpinning with the mode of mourning offered by Ayler and Coleman, the major difference is that the former offers no form of praxis, no means of carrying out this mode of mourning. What makes the modern jazz mode of mourning so vital and important is that it both articulates a strong philosophical underpinning that acknowledges the complexities of grieving in the modern world, while also creating a replicable form through which to carry out this mode of mourning. Coleman and Ayler do not just explain what an ethical mode of modern mourning is—they show how to mourn properly in musical form through virtual signifyin(g). The form of the jazz requiem that Albert Ayler and Ornette Coleman established at the funeral of John Coltrane in July 1967 was a robust ritual, not a cheap, creepy resurrection, but a true communing of the spirit.

Kevin Laskey is a composer and jazz drummer based in Philadelphia. He edits the blog Jazz Speaks and is currently pursuing a PhD in music composition at the University of Pennsylvania.