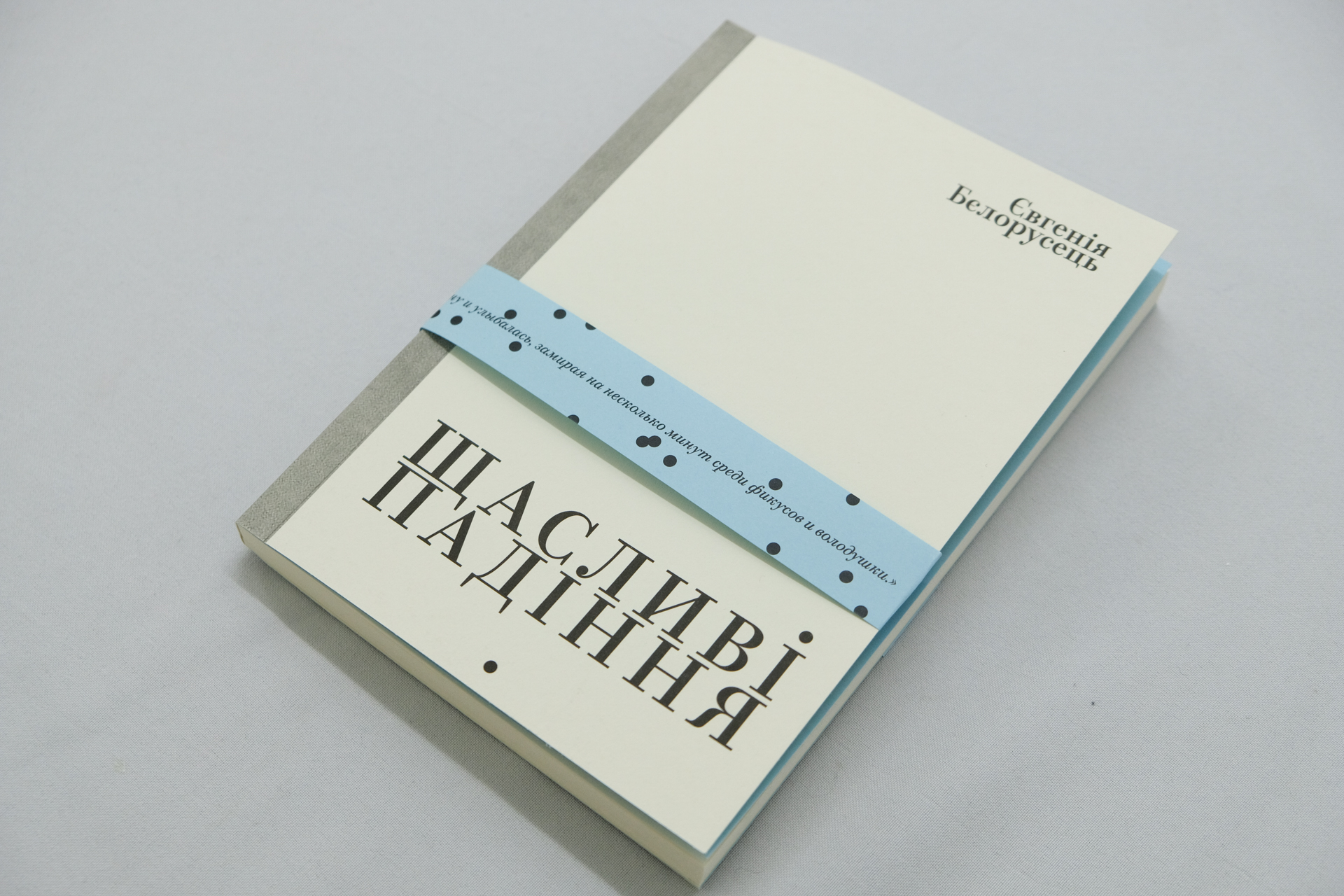

Shchaslivi padinnia (Fortunate Fallings)

Yevgenia Belorusets

Ist Publishing, 2018. 150 p.

Yevgenia Belorusets is a Ukrainian photographer who lives between Kyiv and Berlin. Her photographic work calls attention to the more vulnerable sections of Ukrainian society: queer families, out-of-work coal miners, the Roma, people living in the warzone in the East. She has just published a book of stories called Fortunate Fallings (Shchastlivyie padeniia) about women living in the shadow of the now-frozen, now-thawing conflict in the Donbass region, caused by Russian military intervention after the Kyiv Maidan of 2014. The book’s linguistic eclecticism—the stories are in Russian but the publisher and packaging are Ukrainian—silently defies hardline cultural propaganda in both countries. Apart from being political, Fortunate Fallings is also an astonishingly intelligent, moving, and exquisitely written work of ironic European literature. The publishing house Matthes & Seitz will issue the book in Germany in fall 2019; meanwhile, Music & Literature is pleased to debut two stories from it, “The Florist” and “The Woman with the Black, Broken Umbrella,” both in Eugene Ostashevsky’s English translation, followed by a review of the entire collection by Russian writer Maria Stepanova. These texts are accompanied by several of Belorusets’ photographs from the book.

The Florist

The florist is a woman who loves flowers. As for me, I confess, I was for some consecutive months in love with such a woman. The florist has a better grasp of flowers than anybody else. The words ranunculus and hellebore cannot astonish her. But she very much does like to be astonished—to recoil, her daisy of a face turned innocently toward her interlocutor, to open her eyes widely, grasp the back of a chair with a fluttering hand, set her mouth into an O.

Actually, she took after flowers also in being imperturbable, and even her rare beauty she got from flowers. Each morning she raised the shutters of her store, neared the window and smiled, pausing for some moments in a prospect of aspidistra and bupleurum.

Practically no one ever noticed her astonishingly well-assembled face. I have never seen a passerby stop to admire her. In the afternoon, right after lunch break, she would stand for some time, leaning against the plastic window frame, as indifferent passersby went past and only rarely did anyone enter her flower shop. I liked to look into her store and to study how she gathered bouquets, arranged flowers and branches in vases, cut stems, tore off leaves. The florist was familiar with exotic, barely existing words denoting hues, tints, petals. She pronounced them clearly and with joy, the way a child recites a poem it learned by heart for the first time: Bring them closer to light, these Persian buttercups the color of ivory. She was convinced that her customers bought not so much flowers as their names.

This acquaintance of mine lived in Donetsk and more than anything in the world she loved to make up designations for flower arrangements, bouquets, and flower packages. One winter morning I found her glowing and happy behind the counter. Her brightly painted lips, aptly located in the lower half of her mother-of-pearl face, triumphantly pronounced: Listen, my new names are finished! Attend to their melodic form, but do not forget the philosophical significance, too.

Breakfast in Venice.

Spring Pageantry Wow.

Absolute Spring.¹

A Roman Bedchamber.

An Ukrainian Mystery.

March Spring.

She was waiting for my approval and it was granted. She had made up bouquet names for the next season—it was to be spring—and she counted on its rapid approach.

The florist was a successful, practical woman, with an excellent understanding not only of flowers, but also of book-keeping. At the same time, she was entirely unsuited for real life. As she herself frequently told me, only inside her store, which at some moment became the meaning of her life, did she know how to exist. She decided to abolish weekends even, and in the winter of 2014 she was working on Saturdays and Sundays.

What is this story I am telling about? Does it make any sense to continue? In fact the story does not exist, the narrative does not continue, it breaks off. The florist disappeared. The house where she lived was destroyed. Her store was refitted into a warehouse of propaganda materials. Her regular customers left Donetsk long ago.

Not long ago and purely by accident I met up with one of the people who had often bought flowers from her, and he confessed to having heard something of the florist. He said she went off into the fields and joined the partisans. That’s exactly what he said: “went off into the fields.” But on what side her partisan unit is fighting and where those fields are, he had no idea. The florist, he reminded me, never had a sense for politics. She was a sort of a flowerworm: she even divided people into different kinds of flowers. She had never seen anything in life other than flowers, he lamented.

“She must be fighting on the side of the hyacinths,” he suddenly declared and broke into laughter. We fell silent, and then he looked at me and waited that I give his sense of humor its due. “Time is passing, I am getting cleverer, I am beginning to understand which way the wind is blowing, and where we’re going to,” he added. “I am not the person I was. You can’t fool me at one try! Kyiv has taught me a thing or two. It’s not our naïve Donetsk. But I still have my sense of humor at hand. I don’t have to rifle my pockets for it.” And he again broke into laughter and walked off, with a triumphant gait, to follow his business.

¹ Translator’s note: original in English.

The Woman with the Black, Broken Umbrella

Kyiv, March 2016

I don’t want to write about her, I have no wish to recall her. She forgot her umbrella at the bus stop—believe me, there’s no need to recall that incident—then she was going to the bus stop in the pouring rain in order to pick it back up—if I remember correctly—and then, when she finally took it into her hands, could not manage to open it.

It seems it was her last umbrella.

Can anything be more affecting than events of this sort: lacking an umbrella, striving to possess it, this fluttering hand extended in its direction? Perhaps only the need to think and speak of such insignificant, trivial things.

A man’s umbrella, medium-sized, semi-automatic. A black inkblot.

The bus stop: a transparent cage. She was stealing toward that spot of black in the rain, going for it—and in the meantime, as she communicated to me afterwards, recalled as, not long ago, in another city, she had gone under bullets for some black rag. She recalled her tremors, her stupidity. This woman moved to Kyiv from a region where the war is being fought—but here, against all common sense, went on with her wartime habits, her wartime tricks of desperate intercourse with objects, things, the street.

I didn’t want to talk about her at all, it’s painful for me to recall her face, slit up by the thin rifts of wrinkles. She said the same things too often. But lately I’ve been doing that also. She made overly insistent attempts to explain her despair to me, she wanted even more—for me to put a high value on the pain, agitation, and fear that do not let her rest.

I will never manage to shed light on that abiding bewilderment, the inability to concentrate that never loosens its grasp, I can only try to reproduce it, to list its existential forms: the sudden lurch from the house to the bus stop for the umbrella, the fit of wrestling with it, the engagement to be blamed for the flight of a coat button, recently bought and resewn, while the spokes strip and cast a shadow across the face. The umbrella will not open. It is abandoned in wrath on the bus stop bench, and then ensues the rush to the closest café for a breather. Although it’s not even a café but an unprepossessing kiosk on the Boulevard of International Friendship. Here they offer bad coffee for 8 hryvni, and for 6 will pour a glass of tea. Our eyes meet each other. She commences her eternal lament, she sings it to the kiosk woman. The kiosk woman looks at her with envy, for she is a free woman whom the rapacious and venal kiosk owner does not hold in her paws.

The kiosk woman says: These blocks of butter here have almost melted. I would have liked to butter myself, I would have smeared the butter all over me, I wouldn’t have spared even my hair, because in this kiosk your skin turns to tin. I both sleep and live here, I’m cooped up here the whole week. Only sometimes for a half-hour I dash off to the house next door—to brush my teeth, wash my face—otherwise I’m here, there’s no going outside, like a bunny in a terrarium.

Both women are anxious. Neither knows what to do with herself. As for me it is by chance that I happened near them, and we succeed in holding a conversation for some measly fifteen minutes.

And the woman who had been going for the umbrella, who has just now caught her breath, again wants to take off from where she is, to run under snow and ice to the bus stop to take back her umbrella, which she abandoned in the middle of an iron bench at the bus stop, and it lies there like a black stain, like a crushed tube of paint or an indefinite ink spill. She left it at the bus stop even though it had allegedly gone through unbelievable hardships with her, the things that umbrella had seen over the last year, what hadn’t it lived through.

The kiosk woman tries to hold her back, appealing to her common sense, reason, dignity, honor, and pride, and also to her not having finished her coffee yet.

At the end the woman throws us a cunning look in which I read pity and disdain, and says that in any case she must buy some milk at the Lybedskaia metro and she will now go in that direction, past the bus stop, naturally.

She tears herself from us. Quickly, stumbling and jumping over small obstacles, as if dashing for the next shelter, she careens to the bus stop, takes the umbrella into her hands, and attempts to open it. We’ve seen it all before! Pointless.

But now she does not throw the umbrella back on the bench, she takes it into her hands and begins going somewhere aslant, in the direction of a small park, and I am going after her for some reason, I am nearing her.

I hear what she says to her umbrella: You black scab. What did I buy you for. You always go about dirty, sick, infected. You can never be by yourself. You’re all gnawed up by illnesses and infections, you’re a scab, and I’m going to get rid of you, believe you me. I won’t act like I’m sorry for you anymore. I carried you into the park yesterday, I left you on a bench by the trash bins, but you lay out your term, you bastard, you abortion, you waited me out. But today I’m gonna carry you into such wilderness that lying around will get you nowhere, you’ll be lying around for nothing, you thankless wretch. When I was asking you to be like everyone else, to do what you’re told, you just had to have it your way, you wretch, you. When I was cleaning, washing everything around me which means you also—it was like zero fudge, you just went on being yourself. That’s what you care about. To be yourself! But I can’t do this anymore! I’m at the end of my rope! I forgot the last time I was myself! I’m exhausted! I’m sick and tired of tending to you everywhere, sick and tired of coming to your rescue. So you just stay where you are, friend, I am going off to Lybedskaya. Believe me, it’ll be easier that way for you and for me.

She disappeared behind one of the buildings. I would not follow her any longer.

Translated from the Russian by Eugene Ostashevsky

***

A review of Fortunate Fallings

“War disarms? War takes away hope, meaning, makes the entirety of life grey, sucks life out of the city, the street? What are you saying? War helps us! We now have the luxury of taking our minds off ourselves, we can give self-reflection a rest. For some time now we have taken peeks into who we are only in the mirror of war.”

Fortunate Fallings by Yevgenia Belorusets was written about war, near a war, at the time of war. It has a Ukrainian title, and it was written in Ukraine. But it was written in Russian. But the author’s introduction is in Ukrainian, and the publisher is Ukrainian, although far from all Ukrainian bookstores stock it: for the very reason that it is in Russian. Each of these facts matters—and each new fact softly displaces or contradicts the ones that precede it. Together, they might be said to prevent the reader from taking aim—except that, since the book was written about war, we must choose other words. It is a book in Russian about the war in Ukraine that does not describe combat operations and that forbears to generalize in any way.

Everything that lies at the heart of military life here appears haphazardly, in passing, like something too obvious or too vital for mention. It just so happens that some protagonists, who come too close to the center of events, unaccountably disappear, but even that fact warrants no explanation. Neither does it seem worth remarking that all the actors of this spacious and teeming text are women, that men don’t come by here much. But when one of them does appear, he makes no bones about it, he says that he married war.

It’s a good summary of the situation that Belorusets, as chronicler and investigator of human history, works with. There is a classic love triangle where, as in the days of Lysistrata, the man must choose between woman and war, and there is the female choir that separates into a multitude of different voices and stories. Each story imagines itself to be not about war but about peace. The love rival remains anonymous. The leading ladies have more pressing business to attend to: they put together hairdos and bouquets with names one wants to cite in their entirety, like the classmate list in Nabokov’s Lolita: “Breakfast in Venice. Spring Pageantry Wow. Absolute Spring. A Roman Bedchamber. An Ukrainian Mystery. March Spring.” They visit the cosmetologist, they look for a job and they find it, they get ready to visit Paris, they behave rationally or inexplicably, they sit in a lightless cellar, they read horoscopes, they organize rebellions and create city-states. All of this happens somehow aslant, slowly and incorrectly, as if the normal order of things shifted, things lost their balance or froze midair, and you now have to take that into consideration, whether you are a hairstylist or a journalist, you have to behave accordingly.

This shifting or displacement has a name that is never spoken aloud. It’s then happened the thing that happened: no need to explain, everyone understands anyway. The country with its small and big cities now has a displaced center of gravity, like a bullet. You think that the Russian language the book is written in, that I am writing my text in, is overladen with military metaphors, just like an armory, whose arms can at any moment be distributed among the civilian population for self-defense: here’s another such metaphor. The center of gravity or of something other than gravity, elusive and ineffable, now lies where there once transpired a life that has nothing in common with life at present. The protagonists, many of whom are refugees, think of themselves as has-beens. To be, like one of them, a woman formerly from Alchevsk, in the contested Luhansk region, becomes the support structure for a new identity, one that hasn’t been worn in yet: an identity of which all we know is that it’s irreversible, the old rules don’t apply anymore, the world is never to go back to being what it was. This is the point at which the tender and terrible stories of Yevgenia Belorusets, where bogeyman tales of childhood dress in the language of Jean Genet, and the documentary dilates into the epic, become the history we all have in common. It is essential in our time that we learn about people trying to survive in a world that has irreversibly changed, since just about any one of us can become one of them: one of those who “went into the fields and is fighting on the side of the hyacinths.”

—Maria Stepanova

Yevgenia Belorusets is a photographer and filmmaker working at the intersection of art, literature, journalism, and social activism. She has taken part in several Ukrainian and international exhibitions featuring socially critical and engaged art.

Eugene Ostashevsky is a Russian-American poet residing in Berlin. His latest books are The Pirate Who Does Not Know the Value of Pi and The Fire Horse: Russian Children’s Poems by Mayakovsky, Mandelstam and Kharms.

Maria Stepanova is the author of several books of poems and the recipient of numerous literary awards, including the Andrei Bely Award (2005) and a Joseph Brodsky Memorial Fellowship (2010). Her latest novel, Post-Memory, won Russia’s 2018 Bolshaya Kniga Award (The Great Book), and is forthcoming in English with New Directions and Fitzcarraldo Editions.

Banner and image credit: Yevgenia Belorusets. All reproduced with permission from the photographer.

Stories translated and published with permission from Verlag Matthes und Seitz.