Editing Blue Light in the Sky was one of my most rewarding experiences while working at New Directions, and I was really thrilled to receive an email from Can Xue recently saying she thinks it is one of her best works ever published. The biggest challenge for me in editing the translation was latching on to the style and hearing the voice. I might be wrong, but I think Can Xue emphasizes mood and story over highly stylized prose. Her voice is deliberately flat. Western literature draws on sources with which we’re all familiar: the Bible, Shakespeare, Homer, Dante. Can Xue’s biggest influences are writers like Kafka, Dante, Goethe, and Calvino, though I’ve read arguments elsewhere that her writing is rooted in emotion and landscape. I believe this is true. Her writing always conveys the constant threat of chaos lurking beneath. That said, the challenge of my job as editor was to see the arc in each story and make sure the sentences were correct, that the paragraphs flowed, and that the arc emerged clearly in each of the stories. As I said before, Can Xue’s stories are to me like modern abstract paintings, demanding the reader’s engagement in that particular way . . .

A feature by Paul Kerschen

Can Xue’s Five Spice Street is among other things an author’s reflection on her newfound public position. The book was originally published as Breakthrough Performance (突围表演), a purposely self-conscious title for a debut novel. At the same time, 突围 suggests breaking free, an escape from entrapment or other immediate danger, and this raises the possibility that the escape itself constitutes the performance, that a kind of Houdini act is being staged . . .

Kronos first met Kaija in the summer of 1984 at the Darmstadt Festival of New Music. I remember it was the same summer that we played Morton Feldman’s big and beautiful String Quartet No. 2 there. And it was the same festival where we met Kevin Volans, the South African composer who would go on to write White Man Sleeps and Hunting:Gathering for Kronos—very important works in our repertoire, and among the first string quartets ever by an African-born composer. So in meeting both Kaija and Kevin, Kronos began two very important relationships that summer . . .

Stig Sæterbakken is one of the most important Scandinavian writers of my generation. His novels in many ways resemble paintings by the Danish artist William Hammershøj: scenes of one or two persons in an otherwise empty room, painted in shades of white, gray, and black. The models often turn their back to the viewer. Occasionally you glimpse a pale face in a mirror. There are sometimes endless corridors, and open doors that lead to a room with more open doors leading to yet another room with yet another open door, and, behind that door, darkness.

Galehaut: I am a character.

Violin: Perhaps I am too. I have no physical existence. I am not an object, though I need a certain class of objects—wooden boxes with strings and a bow—to be heard in the real world. I am represented, bodied forth, by these objects, just as you are by a voice, even a silently reading voice. I am not to be identified with the object that renders me, nor with the musician, any more than you are with the voice relating your words, or the reader or actor whose voice this is.

When Kaija Saariaho describes her 1994 composition Graal théâtre as being “for violin and orchestra,” or as a “violin concerto,” we may imagine her to have had in mind a musical instrument in its actuality, including its tuning and its responses, and we may suppose her to have been considering also Gidon Kremer, her destined performer, but she will have been thinking not only of but through these manifest conditions of her work, to me, to an entity whose features are not materials and dimensions, not personality and technique, but sound, and a design for sound, and experiences of that sound through time.

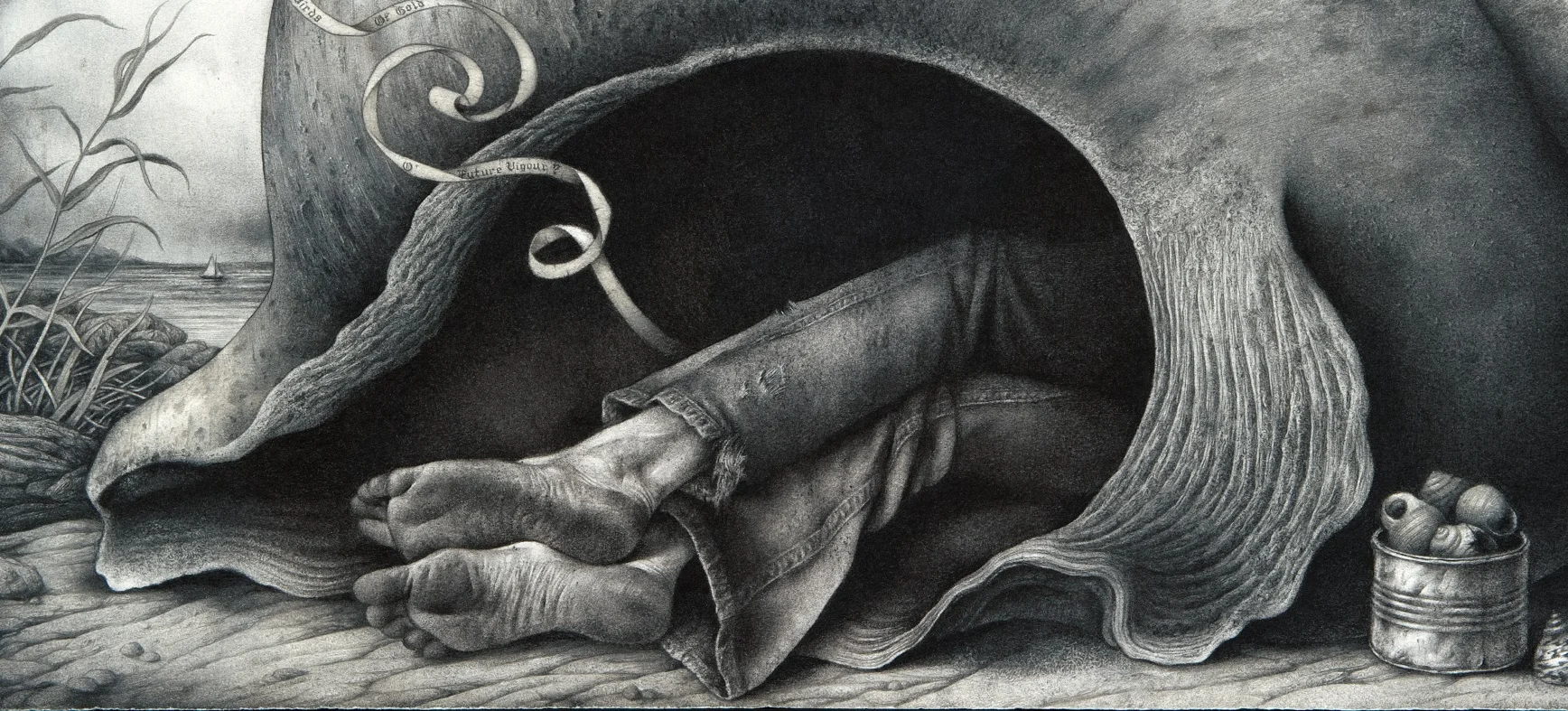

A wonderful sense of being consumed, this is what the Vigeland mausoleum offers its unprepared first-time visitor. But the feeling does not fade through repetition. On the contrary, I’d say. As if the knowledge of what awaits you heightens rather than diminishes this overwhelming sensation. And I guess that’s why so many visitors keep coming back: they want to be devoured again. And again. And again. And isn’t that what drives us, repeatedly, toward art in any form, the dream—however often it leads to disappointment—of being overpowered, shocked, overcome by horror and joy, the stubborn dream of becoming one with the object in question, melting into it, rather than standing at a distance watching it, analyzing it, evaluating it, in other words: the dream of being swallowed, digested, and spat out again, presumably dizzy, definitely shaken, thoroughly and utterly confused, as we re-enter the so-called real world?

A feature by Clément Mao-Takacs

Clément Mao-Takacs: I would like to start by clearing up a few clichés that have been said about you. To name a few: You’re from Finland, therefore, you love and get inspired by nature; you are “a fiery volcano beneath ice”; since you live primarily in France, you inevitably subscribe to French music. Can we try to make sense of some of these common preconceptions? Let’s start with the nature-Finland parallel.

Kaija Saariaho: I think there is some truth to the connection between nature and Finland. The country’s population size is so small and nature’s presence there is so important, that it’s impossible to live the kind of urban life you’d have in a big capital—even though some people try desperately to pretend they do. Nature is one thing, but what’s more important is light. Changes in sunlight throughout the year are so drastic that it affects everyone. You can’t escape it when you live there. And because of this experience—which is so physical, we feel it in our body—we have a very special relationship with nature. We have respect for it, we are aware that it’s something larger than us; and also, there are things that are a part of our culture, which can be seen in Finnish epic poems where nature is truly sacred—as is the case for many early cultures. For me, it really comes from this experience of living in the “period of darkness”—there’s a very specific term for this in Finnish: kaamos—all the while having hope for the sunlight to start strengthening again until it is fully restored. Springtime is extremely long, and since the earth has been covered in snow for such an extensive period, there’s a kind of rotting—but pleasant—smell, which gradually gives way to spring vegetation. My relationship with nature isn’t about admiring the aesthetics of a sunset; it’s something much more physical that I carry inside me . . .