Galehaut: I am a character.

Violin: Perhaps I am too. I have no physical existence. I am not an object, though I need a certain class of objects—wooden boxes with strings and a bow—to be heard in the real world. I am represented, bodied forth, by these objects, just as you are by a voice, even a silently reading voice. I am not to be identified with the object that renders me, nor with the musician, any more than you are with the voice relating your words, or the reader or actor whose voice this is.

When Kaija Saariaho describes her 1994 composition Graal théâtre as being “for violin and orchestra,” or as a “violin concerto,” we may imagine her to have had in mind a musical instrument in its actuality, including its tuning and its responses, and we may suppose her to have been considering also Gidon Kremer, her destined performer, but she will have been thinking not only of but through these manifest conditions of her work, to me, to an entity whose features are not materials and dimensions, not personality and technique, but sound, and a design for sound, and experiences of that sound through time.

A feature by Jesse Ruddock

Avishai Cohen has been working since he was ten, when his job was to stand on a soap box and play trumpet for a big band. Raised in Tel-Aviv, the youngest of three jazz prodigies in one house, his music is persistently lyrical, often sublime, and intensely playful. Cohen stands out on stage in a way that’s athletic: his lead’s to follow. What the body has to do with the soul can be heard in the tone of his trumpet, that strange precise math of breath and spirit. On Dark Nights, the third and latest album from his trio Triveni—with Omer Avital on bass and drums by Nasheet Waits—Cohen’s tone is clearer than any voice. The songs all go slow but never keep you waiting to find out what they’re trying to mean. This interview took place high above Broadway Avenue in Manhattan, one afternoon before Cohen played three sets through midnight with the Mark Turner Quartet . . .

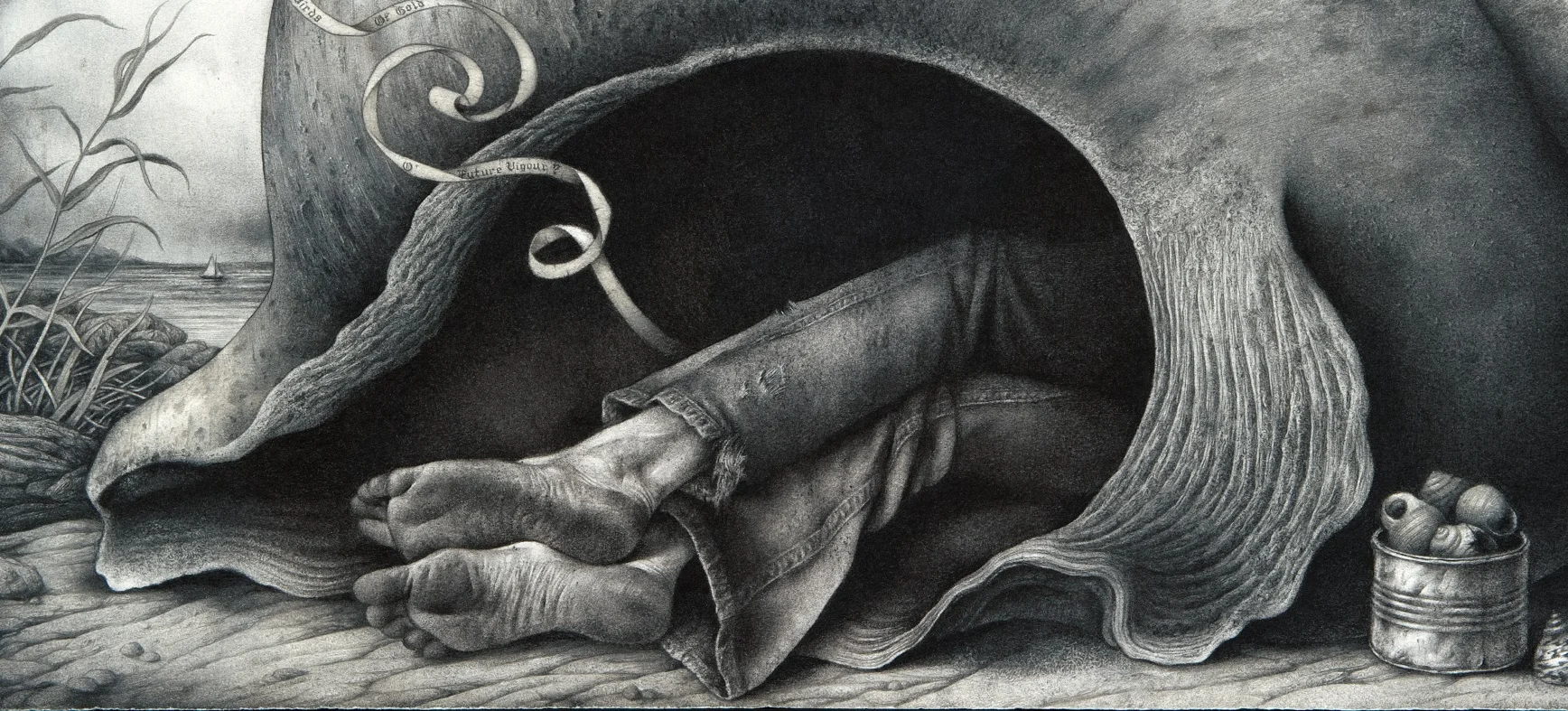

A wonderful sense of being consumed, this is what the Vigeland mausoleum offers its unprepared first-time visitor. But the feeling does not fade through repetition. On the contrary, I’d say. As if the knowledge of what awaits you heightens rather than diminishes this overwhelming sensation. And I guess that’s why so many visitors keep coming back: they want to be devoured again. And again. And again. And isn’t that what drives us, repeatedly, toward art in any form, the dream—however often it leads to disappointment—of being overpowered, shocked, overcome by horror and joy, the stubborn dream of becoming one with the object in question, melting into it, rather than standing at a distance watching it, analyzing it, evaluating it, in other words: the dream of being swallowed, digested, and spat out again, presumably dizzy, definitely shaken, thoroughly and utterly confused, as we re-enter the so-called real world?

A feature by Nell Pach

The previous century saw the explosion of magic realist fiction, texts where daily life and the fantastic filter through each other. The continued development of a genre that steps away from straight realism seems not just likely but, paradoxically, necessary for effective artistic representations of the real and the human. Can Xue's The Last Lover, at once alien and familiar in its casual miracles, its people and things that blink in and out of solid existence, and its radical reconsideration of subjectivity, reads like an inaugural, or at least transformative, text. Call it magic virtual realism. We are perhaps overdue for a literary approach to this new form of human experience. Most of us now live substantial portions of our lives within a cyber-sphere of kaleidoscoping stories, dialogue, and images. We waft in from all parts of the analog world to hold either infinitesimal or prolonged intercourse with people who appear, like us, out of nowhere; we friend them, fight them, not infrequently doubt their existence or aspects thereof. We share moments of feeling we don’t understand, we slide into oblivion or obliviousness with a click. We have come perhaps closer than ever to something that resembles a dreamscape in sober waking life . . .

A feature by Clément Mao-Takacs

Clément Mao-Takacs: I would like to start by clearing up a few clichés that have been said about you. To name a few: You’re from Finland, therefore, you love and get inspired by nature; you are “a fiery volcano beneath ice”; since you live primarily in France, you inevitably subscribe to French music. Can we try to make sense of some of these common preconceptions? Let’s start with the nature-Finland parallel.

Kaija Saariaho: I think there is some truth to the connection between nature and Finland. The country’s population size is so small and nature’s presence there is so important, that it’s impossible to live the kind of urban life you’d have in a big capital—even though some people try desperately to pretend they do. Nature is one thing, but what’s more important is light. Changes in sunlight throughout the year are so drastic that it affects everyone. You can’t escape it when you live there. And because of this experience—which is so physical, we feel it in our body—we have a very special relationship with nature. We have respect for it, we are aware that it’s something larger than us; and also, there are things that are a part of our culture, which can be seen in Finnish epic poems where nature is truly sacred—as is the case for many early cultures. For me, it really comes from this experience of living in the “period of darkness”—there’s a very specific term for this in Finnish: kaamos—all the while having hope for the sunlight to start strengthening again until it is fully restored. Springtime is extremely long, and since the earth has been covered in snow for such an extensive period, there’s a kind of rotting—but pleasant—smell, which gradually gives way to spring vegetation. My relationship with nature isn’t about admiring the aesthetics of a sunset; it’s something much more physical that I carry inside me . . .

A feature by Keenan McCracken

One of contemporary American fiction’s most lauded and prolific novelists, Richard Powers might also be described as the autodidact’s autodidact. An amateur musician and composer, former physicist, and self-taught computer programmer, Powers has become known for his deftness at tracing out the subtle interrelationships between science, art, and politics with a lyrical virtuosity and breadth of intelligence that have elicited comparisons to writers from Melville to Whitman to David Foster Wallace.

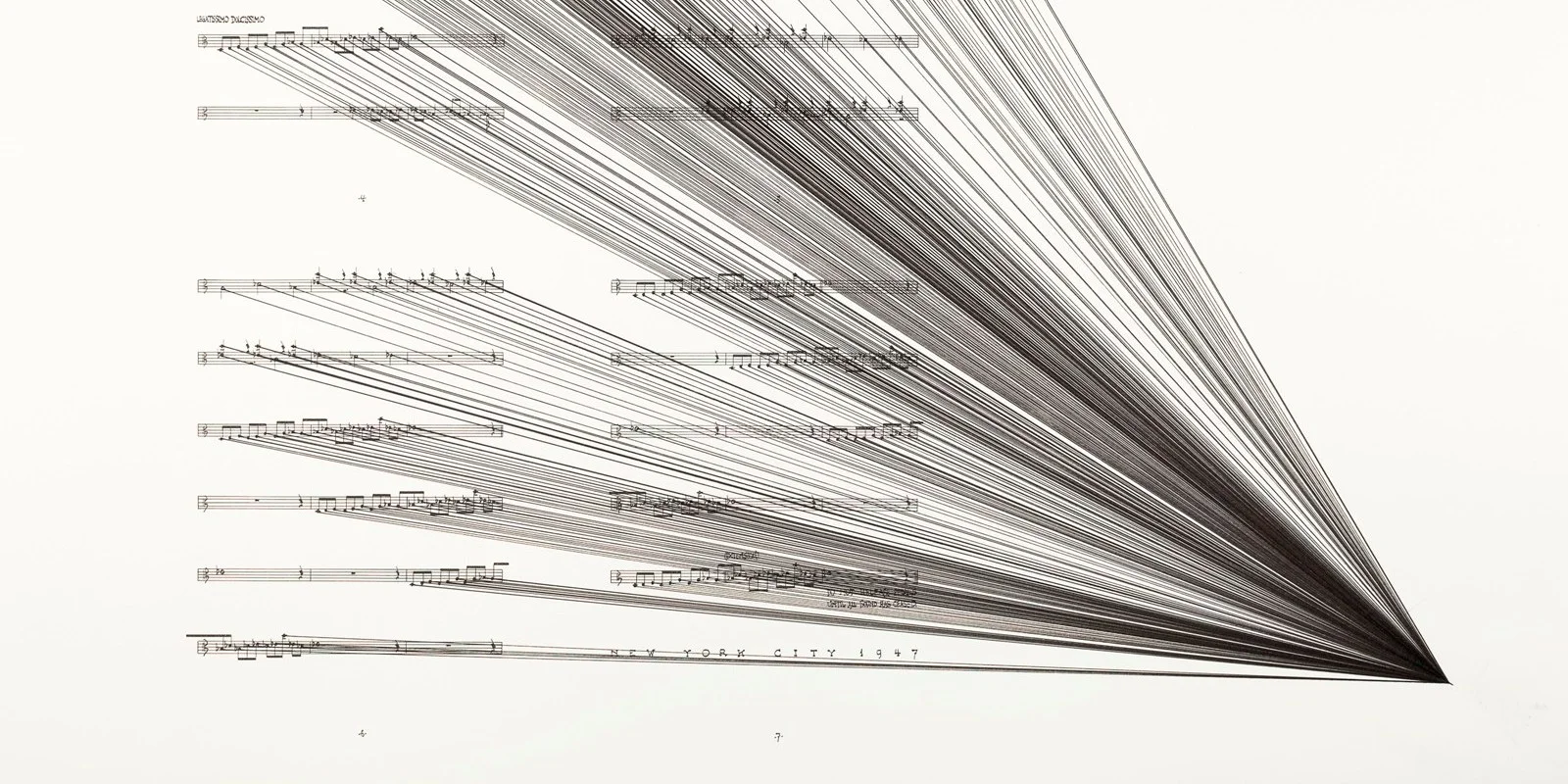

In his most recent novel, Orfeo (2014), Powers examines the post-9/11 political landscape through the life of avant-garde composer turned amateur chemist Peter Els, whose Orphic descent into the underworld of twentieth-century composition and lifelong fascination with patterns lead him to attempt encoding music into the DNA of a living organism. The third of his novels to use music as a centerpiece (after The Time of Our Singing and The Gold Bug Variations), Orfeo is yet more evidence of Powers’s rare gift for articulating the seemingly ineffable qualities of sound, one that is accompanied by a near-encyclopedic knowledge of music history. Incredibly kind and generous, Powers spoke with me via Skype about his new novel and how music factors into his vision . . .

A feature by Christiane Craig

The Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho's oratorio La Passion de Simone has, over this past year, been re-imagined by Saariaho, adapted specifically for conductor Clément Mao-Takacs’ nineteen-piece Secession Orchestra, vocal quartet, and soprano soloist Karen Vourc’h. This smaller cast, under the stage direction of Aleksi Barrière, provides a more direct and unmediated experience of Saariaho’s sound materials. The expansive tonal force of La Passion de Simone’s first production, an oceanic work for full orchestra, choir, and electronics, has been consolidated but not reduced in the chamber version, its sound colors intensified by a microscopic quality of vision that is perhaps better adapted to the piece’s investigation of human, as well as sonic, interiorities . . .

A feature by Daniel Levin Becker

The formal resemblances between Édouard Levé's Works and Georges Perec's I Remember pale away compared to their spiritual perpendicularities: one is an assemblage of purportedly original things that do not yet exist, the other a motley litany of things that once existed but never truly belonged to anyone; one is a series of ideas abandoned at the moment before they crystallize, the other a series of memory-points that exist to be shared and collectively reified. Perec had none of Levé’s impulse toward detachment; the questing in his work was driven by his interest, on some level a desperate one, in the way people could be objectively united in their subjective experiences of time and place, even if they shared neither. Whereas Levé was fascinated by people from a remove, Perec wrote in enormous part to remind himself that he was one of them . . .

A feature by Ian Dreiblatt

Carnegie Hall, May 31, 2014. I watch Arvo Pärt step haltingly into the rear of the auditorium. An usher, thinking him the old man he appears from outside of sound to be, asks if he needs any help, a faint impatience curling the edges of his speech. He shakes his head and proceeds to an aisle, occluded by clusters of Orthodox priests. He navigates among them slowly and without solemnity. Like the people around me, I’m anticipating the concert by remembering things. A procession of them, connected by an invisible logic that feels somehow singular. It’s like mourning. Slow motion up a chain of small bells . . .

A feature by Caio Camargo

Chico Buarque has become a living icon of Brazilian culture. For his seventieth birthday, he was the subject of countless homages and retrospectives, with an admiring piece on nearly every media outlet and birthday greetings and messages from a who’s-who of recording artists and other assorted personalities. The only notably absent voice was from the man himself. From the (relatively rare) interviews he grants, it is clear that he never felt comfortable in the shoes of his legend. Chico seems to make a point to puncture the inflated image, to paint himself as just a guy devoted to his art, who also happens to love soccer and going to the beach. But there is hardly any escape from the fact that he remains, after a decades-spanning career, a defining cultural touchstone. His work bears a great sense of history and politics, a connection to the land of his birth so strong that it is difficult to imagine Chico without Brazil, and impossible to imagine Brazil without Chico . . .

A feature by Declan O’Driscoll

How do you compose? At a piano?

Yes and no. My compositions start their lives with reflections upon paintings, architecture and of course musical possibilities. So, before I really use the keyboard I normally accumulate various sketches that indicate (possibly) movement, energy, pitch areas and outline structures. The keyboard is used later in the process to confirm pitch relationships, note rows and other procedures that help during the composing process. If I ever wrote a piece based only upon my keyboard expertise, the composition would be destined for the trash can.

A feature by Declan O'Driscoll

The following interview was conducted for the occasion of Music & Literature No. 4, which includes some 80 pages of new interviews, graphic scores, poems, appreciations, and other writings on and by the musical duo Maya Homburger and Barry Guy . . .

A feature by Gábor Schein

The themes of memory and forgetting are not as distinct from the theme of responsibility as we would like them to be. Gábor Schein's beautifully developed and persuasive essay begins with the physical description of a specific part of Budapest, tracing it from its origins as a swamp through its development as an industrial slum and then as a quarter for the wealthy, going on to examine the regular changing of the city's street-names as a series of excisions from memory. Such excisions, he argues, lead to apathy and indifference. Corpses float down the river in 1945 but no one notices any more. The homeless and hungry of today move past us in the street but liberal public opinion uses them more to flatter its own conscience than to do anything. The Sebaldian sense of deep ground constantly opens at our feet but we move on, returning to the moral and psychological equivalent of the swamp out of which the city sprang . . .

MICHAEL BARRON: What prompted the inception of Music & Literature? Could you describe the process from idea to publication?

M&L: Roberto Bolaño described his dream reader as the sort of person who engages with the complete works of an author. There’s an impulse behind this project similar to the drive to read every word by a writer like Dickinson, Kafka or—to choose a more recent example—Bolaño. Among the greatest delights of assembling each issue is the nature of the labor required: total submersion in the cosmos of a superlative artist. To my knowledge, no other journal comes close to satisfying this thirst for depth and sustained attention. In a publishing climate where commercial “viability” determines content, there’s a genuine need for such unapologetic focus. Despite its own host of challenges, being a not-for-profit assures us greater freedom of inclusion than most other editors enjoy. Quality and relevance determine the content, not word count or precedent.

A feature by Bradley Harrison

The following conversation appears in Music & Literature No. 4, which devotes some 90 pages to coverage of Mary Ruefle's entire published catalog to date and includes portfolios of new poems and erasures . . .

A feature by Reif Larsen

What makes Where You Are so fascinating is its dual existence as a box containing sixteen physical booklets and a website, where-you-are.com, to which this content has been ported. While many print books have attempted a similar multi-platform extrapolation, Where You Are seems particularly suited for a dual paper/digital edition given some of the central themes of the project, which seeks to explore how we locate ourselves in a swiftly changing world and how these methods of location have changed since the rich mnemonic stomping grounds of our childhood . . .

A feature by Paul Kerschen

László Krasznahorkai's 2014 Best Translated Book Award for Seiobo There Below—presented in Ottilie Mulzet's expert translation—serves to cement the Hungarian's status as one of the most original writers. And yet, only a portion of Krasznahorkai's extensive catalog is currently available to Anglophone readers. Here, Paul Kerschen delivers a masterful reading of the award-winning Seiobo There Below and offers a glimpse of what awaits us in coming years, including Destruction and Sorrow beneath the Heavens (forthcoming from Seagull Books in Ottilie Mulzet's rendering), The Prisoner of Urga, and Krasznahorkai's debut short-story collection, Relations of Grace. This essay, originally published in Music & Literature No. 2, is accompanied here by a series of photographs documenting the author's encounter, organized by Osaka University and held at the temple of Hōzan-ji, with the original manuscripts of the fourteenth-century Japanese actor and Noh playwright Ze'ami, whose spirit infuses Seiobo There Below, and whose influence is felt throughout much of Krasznahorkai's as-yet-untranslated oeuvre . . .

A feature by CJ Evans

The closing lines of Clarice Lispector's novel The Hour of the Star open a fascinating conversation about the Brazilian author's transgressive and hugely influential life, as a public literary figure and as a private person. Her works have inspired an astonishing range of artists, from novelist Colm Tóibín to film director Pedro Almodóvar. Here we join two of Lispector’s translators, Idra Novey and Katrina Dodson, and acclaimed writers Micheline Aharonian Marcom and Hector Tobar for a lively, 80-minute exploration of the infamous life and dazzling work of one of the twentieth century’s great innovators . . .

A feature hosted by Sarah Gerard

For Brazilian writer Hilda Hilst, writing was a continuous process of transcendence without ever reaching the transcendent; a radical subjugation of all traditional or seemingly “correct” modes of thought. A prodigious student throughout her life, she wrote in part to engage and challenge world thinkers, and drew from an incredibly wide set of traditions and fields of thought, including psychoanalysis, spiritism, Gnosticism, EVP (or ESP), pure mathematics and philosophy, biology, astronomy, and quantum physics. Her prose is ludic and polyphonic—physical and titillating—and often challenges a reader’s notions of what is sexually “appropriate.” This roundtable on Hilst is convened on the occasion of the translation and publication into English of three of her novels in less than two years by the American publishers Nightboat Books, in collaboration with A Bolha Editora, and Melville House. Our panel gathers six authorities on Hilst’s work, including four of her English-language translators and two of her publishers . . .

A feature by Benjamin Dwyer

British composer and double bassist Barry Guy is sui generis among modern artists. Guy is at once an ardent student of early and Baroque music and a master improviser across all musical genres, an architect and a Samuel Beckett devotee, who, by age 13, was immersed in the life of a professional musician in southeast London. Guy has served as principle bassist in virtually every major London orchestra, and his compositions for large improvisational ensembles as well as chamber and solo works have been performed internationally. Now Barry Guy speaks in an extensive, retrospective conversation with composer Benjamin Dwyer about his earliest musical impulses, jamming with Sonny Boy Williamson in the back of a liquor store, studying with legendary Greek composer Iannis Xenakis, collaborating with his wife and musical partner, the Swiss Baroque violinist Maya Homburger, and playing an instrument to the limit of one’s physical capabilities . . .