THE U.S. LAUNCHES OF MUSIC & LITERATURE NO. 8:

poets house nyc / 30 october 2017

yale university / 2 november 2017

The crowd gathering at Poets House NYC

From within the giant windows of Poets House, the room rustled with anticipation as one of Music & Literature’s editors, Daniel Medin, introduced the evening’s participants. He then opened the program with a reading of French author Éric Chevillard’s “Peter and the Wolf,” a tale that relates the unfortunate consequences for a child who, subjected repeatedly to Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf, comes to “permanently associate the instruments with the characters they arbitrarily play in the story.” “[D]on’t get me started on Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique,” concludes Chevillard's text, “[…] a sordid, macabre delirium I’d rather not recount in detail. There may be children listening.”

Kevin Sun speaks to Mark Turner as musician and mentor

After Chevillard stepped away from the podium, Kevin Sun, a student of American jazz saxophonist Mark Turner and a highly accomplished sax player in his own right, noted that he felt honored to speak about Turner, especially since there were other students of Turner’s in the room—students who had taken more lessons than he had. He spoke of Turner’s generosity, recounting his second lesson, which had occurred on Turner’s birthday (a discovery Sun made only after Turner received a call from his wife, Helena Hansen). Sun also related an anecdote from a chance performance the two shared in Beijing while Turner was an invited artist. In the green room between sets, Sun brought out a 1917 American tenor saxophone, a Conn, and a particular valve fascinated Turner and evinced his genuine musical and technical curiosity. Sun described how Turner fixated on a sidekey, admiring with wonder the simple key used often, which on this less sophisticated saxophone allowed for a new kind of direct action-reaction he said he could spend all day exploring.

After Sun’s introduction, Turner then took the stage and played a moving set on saxophone.

Renowned translator Alyson Waters then gave a lively reading from the beginning of her English translation of “Moles,” the story of a pimply brat who haunts the existence of Samuel Beckett by tossing moles into his yard at Ussy. Éric Chevillard continued reading the story in French, from his own original “Les Taupes,” and the audience’s laughter never seemed to cease, whether the words responsible for it where in English or in French.

To represent the issue’s portfolio dedicated to Korean composer Unsuk Chin, Medin then read from Clemens J. Setz’s reflections on the fifth of Chin’s piano etudes, the Toccata, whose notes are “played, as the title suggests, in a short clipped manner” and “assembled into a tremendous multilayered structure to which you can listen many times and always recognize new and seemingly independent patterns” (trans. Ross Benjamin).

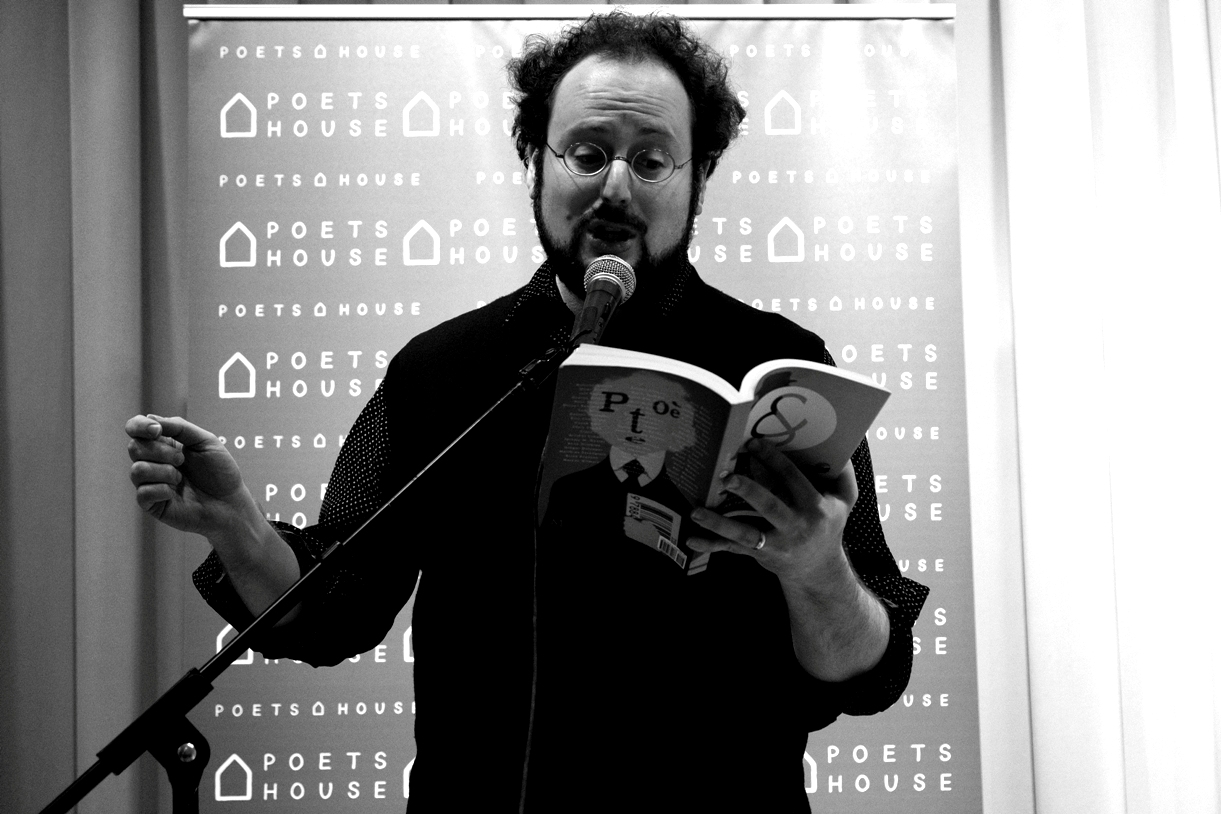

Éric Chevillard reads from a work of short fiction

In his introduction to Jeremy M. Davies, Medin mentioned a coincidence which, at this point, while surprising, didn't seem particularly unusual: Davies’s story in honor of Chevillard was called “Chevillard’s Dog,” and the French writer Pierre Senges wrote a piece included in the issue from the perspective of Chevillard’s dog called “The Author Viewed from Below.” “You don’t have a dog, do you?” Medin asked, to which Chevillard shook his head “No,” turned around to face the audience, and joked, “I have a mole!”

Davies read from “Chevillard’s Dog,” an absurdist homage to the writer’s work in which a visiting author at a university loses his mind as a result of being housed with a dog left by the previous resident, a mysterious French writer. “Why shouldn’t a lamppost be a character, or a bowl of soup, or an abstract concept?” he asks. “I could write a novel that didn’t have any characters in it… or a novel about trying to write that novel, and then a novel defending that novel!”

In the conversational portion of the evening, Davies began by inviting Chevillard to respond to a fellow author’s definition of fiction as “a series of causal events recounted by a narrator, that isn't necessarily true.” The French writer began with a train metaphor to describe the ways in which he uses reason as a vehicle to arrive at absurd conclusions. As Chevillard composed his response orally, his interpreter, Nicholas Elliott, worked to translate his answer in real time. Yet despite extemporizing, what Chevillard generated was highly sophisticated in its syntax and figurative language. “He’s writing as he speaks!” Elliott announced in despair, to the amusement of everyone in the room. One question stood out: “As you begin a project, do you know where you’re headed, or do you discover it through writing?” Chevillard’s response, without hesitation: “I don’t know what will be at the end, I’m not so sure what will be in the middle, and I’m really quite surprised by what I find at the beginning.”

Helena Hansen interviewing Mark Turner

Helena Hansen, a psychologist who is also Turner’s wife, and whose reflection on his life and work is one of the highlights of his portfolio, spoke to her relationship with Turner. She said that she knows Mark well through means adjacent to his music, and asked questions about his background in visual arts and about how his spiritual practice differs from his musical practice. Turner was soft-spoken, and his responses commanded a certain attention. His skills as a teacher shone through as he spoke of voice leading and inner voices, contrary motion and parallel motion in response to her first question. In response to the second, he discussed his Buddhist practice alongside his musical practice and described the ways in which reflective time, expressive time, and improvisation are key to both. Turner concluded, “Life is improvised. You meet people in all different situations, and you have to figure out what to do, and you want to be able to do it in the most elegant, beautiful way that’s beneficial for others. And music’s the same thing. You want to play music that […] benefits others, that creates a beautiful musical situation.”

With the consistent flow of laughter and the whisperings of Chevillard’s interpreter, the spirited room only grew quiet with attention when the words were notes and the language was jazz, eyes trained on the deft movements of fingers moving up and down the keys of Turner’s saxophone. Medin remarked that Music & Literature likes to close on a “last note” as opposed to a last word, and so Turner took the stage once more. “Here we go again,” he said with a smile before beginning yet another transportative solo.

Many stayed and mingled well after the event, buying the issue and chatting with participants. A few of the French translators in the room went over to congratulate Chevillard’s interpreter, who called the experience a treat and a high-wire act. The fantastic program of readings, live music, and conversation made it clear not only that Music & Literature has a devoted following, but why this following is only growing in number and in intensity.

Left to right: Jeremy M. Davies, Éric Chevillard, Alyson Waters, Mark Turner, Daniel Medin, and Kevin Sun

— Liza St. James

— Poets House photographs courtesy of Winslow Smith

The event at Poets House NYC was generously co-sponsored by the French Books Department of the French Embassy in New York, and made possible through the Poets House Literary Partners Program

Daniel Medin, Éric Chevillard, Alyson Waters, and Rick Moody at Yale University

Three days later, the Department of French at Yale University welcomed Éric Chevillard to New Haven as the last of four French authors visiting campus that week. His translator, Alyson Waters, opened the proceedings and read a portion of Prehistoric Times, which Chevillard followed with a reading in the original French of Préhistoire. The bestselling novelist Rick Moody, a Connecticut native and Chevillard devotee, added to the conversation with a tribute highlighting how he first discovered Chevillard’s writing via the Brooklyn publisher Archipelago Press. On that wonderfully temperate day, the group was rounded out by Daniel Medin, co-editor of Music & Literature, who contributed to the question-and-answer section with a delightful extract from Anne Weber’s essay. As the conversation focused on humor and irony in Chevillard’s work, Alyson Waters took the opportunity to share her virtuoso translator’s footnote in Prehistoric Times before Chevillard capped off the afternoon with a reading of “Le Bonnet d’Hegel.” As the talk concluded, the packed audience dispersed into an adjoining space to ask Chevillard all about the present state of French literature while enjoying refreshments from Caseus and the lingering sunshine of an unexpectedly warm Connecticut afternoon.

— Photographs of the Yale University event courtesy of Mina Magda

The event at Yale University was generously co-sponsored by the Yale French Department and the French Books Department of the French Embassy in New York