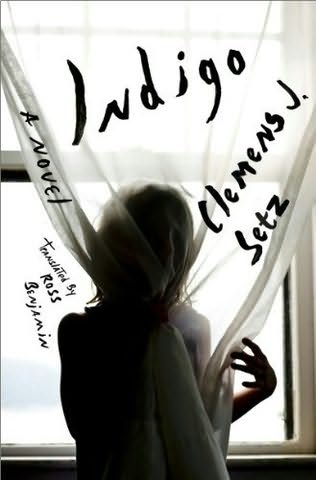

Indigo

by Clemens J. Setz

trans. Ross Benjamin

(Liveright, Nov. 2014)

Reviewed by Patrick Nathan

Apparently, books are supposed to be good for you. Between cardio and kale, scientists say, try thirty minutes of Camus or McCarthy. Late last year, writing for the New Yorker, literary critic Lee Siegel observed, “Perhaps it is appropriate, in our moment of ardent quantifying—page views, neurobiological aperçus, the mining of personal data, the mysteries of monetization and algorithms—that fiction, too, should find its justification by providing a measurably useful social quality such as empathy.” One study, organized by the (consciously liberal-arts) New School in New York, suggests that literary fiction in particular develops a reader’s ability to empathize with other human beings—perhaps, reports the Scientific American, because “Literary fiction . . . focuses more on the psychology of characters and their relationships.” And perhaps it’s true. Perhaps, after years of reading books no one hesitates to call elitist, pretentious, highbrow, difficult, and, occasionally, fancy, a person is more likely to consider another’s feelings before speaking or acting. But empathy doesn’t help me, per se, nor anyone else—why strive for it? Why set aside room in your heart for someone else’s pain on top of your own? In this sense, reading makes about as much sense as hoping to fall in love. But we do that, too, from time to time.

What drew me to Indigo, the newly-translated novel from Austrian wunderkind Clemens J. Setz, was its premise. Setz imagines an alternate dawn to the twenty-first century wherein a new medical condition is discovered: a congenital disorder that causes—in all those within ten yards of the afflicted—intense vertigo, nausea, and headaches. This condition, affecting a small minority of children all over the globe, tends to fade during late adolescence. The not-quite-PC term is Indigo children, coined from a misunderstood and far-from-scientific “study” involving a mystic, the imagined auras of personality types, and a blindfold test: “The seer, who was dressed like a bat . . . couldn’t for the life of her say what qualities that color represented, but she suspected it had to do with the coming of a new age . . . This experiment was somehow judged a success, at least the audience clapped enthusiastically for a long time.” Indigo children, however mistakenly named, are from then on sought out at infancy, a parent’s every headache under suspicion, every sigh of fatigue analyzed for its cause. Since no one is able to withstand contact for more than a few minutes before vomiting or doubling over in pain, Indigo children are—in a depressingly familiar scenario—gathered up and confined to special schools where, scientists say, they’ll be “better off.” The absurd, deadpan history of Indigo sickness is typical of Setz’s novel, where arbitrary circumstances and emotional impulses have catastrophic effects on human lives.

One of these schools is the Helianau Institute in southern Austria, where the classrooms are vast auditoriums with ten or twelve students total, all spaced scientifically apart, and the living quarters are strange, shabby huts that dot the landscape. Because the children affect one another as well as adults, they have difficulty bonding even amongst themselves. From an outsider’s perspective, they appear almost nonhuman. Upon his arrival, the school’s new math tutor (and authorial doppelgänger), Clemens Setz, observes that they move “like wire models of molecules . . . always maintaining the distances between them, as if they were attached to steel connecting pipes.” Setz is hired at the institute right out of university, unable to land a job at a more conventional school. His nervousness is comical from the moment he arrives—the only uncertain, questioning, and empathetic being on a campus that seems populated by robots. The school’s principal, Dr. Rudolph, downplays Setz’s concern over the children’s welfare and isolation:

It’s not about subjecting the children to our understanding of proximity, but rather respecting their own. And that is, unfortunately, it must be said, truly possible only in institutes like this one here. Here they have a social structure they can rely on. A fabric in which they are embedded and . . . and it doesn’t unravel with the first little irritation.

That irritation, winkingly, turns out to be Setz, who despite Rudolph’s not-so-subtle warnings and double-speak begins to investigate what the staff refer to as “relocations”: the sudden disappearances of students who otherwise appear in good standing. Around Setz the narrator’s search and curiosity, Setz the author builds a novel of unique noir journalism, stunning prose, and compulsive readability. Indigo is stuffed (in the good way) with Tarantino-tinged conversations; cryptic news clippings with grainy, Sebaldian photographs to match; nostalgic TV references and Internet memes; epigraphs both real and invented; and a cast of twitchy, anxiously human characters woven into the “fabric” of humanity en masse, no more free to escape their respective prisons than Rudolph’s students.

Naturally, things don’t work out for Setz at the institute. In less than a year, he loses his job. He’s unable to forget the relocated children, however, and he begins to compile information on the Indigo phenomenon, the Helianau institute, Dr. Rudolph, notable Indigo children past and present, and historical data on other minorities and species that have been persecuted, exiled, confined, isolated, ignored, or eradicated. Interspersed throughout the novel are photocopied articles from newspapers and magazines, printouts from websites, and high-contrast photos as though taped to the pages themselves. Each is, ostensibly, some form of “information” deemed valuable and saved in the narrator Setz’s red-checkered folder, yet this information is little more than a catalogue of suffering. Even without Setz commenting on the articles directly—a write-up about the “loneliest telephone booth in the world” or the childhood isolation experiments of Dr. Harry Harlow—his presence is so frenetic that we can almost see him twitching, rubbing his temples at the senselessness of a species that seems only to want to cause its members pain, not to mention any higher being that refuses to intervene. Why, Setz wants to know, does the world happen this way? For what reason would something as terrible as Indigo sickness exist? In what world would a child biologically forced into solitude feel at home? In what world would he belong?

Simultaneously, the novel follows Robert Tatzel, a former student of Setz’s at the institute, all grown up and “burnt-out”—which is to say, no longer symptomatic. Robert’s life is dislodged from its stasis when he reads about the acquittal of murder suspect Clemens Setz—indeed the same Setz whose brief term at Helianau Robert remembers quite clearly. In this future timeline, Setz’s guilt is almost certain, but without evidence, the brutality of his crime—“Death by slow flaying”—will go unpunished. So then does Setz the author set Indigo in motion, Setz the narrator in pursuit of the truth surrounding his former students’ fates, and one of his former students—fourteen years in the future—pursuing the truth surrounding his former professor’s crime.

At the point in Indigo where Robert reads of Setz’s acquittal, it’s no surprise to the reader that Setz’s victim was an animal abuser who “kept his dogs in a dungeon for years.” In the very first chapter, we learn that Setz cannot stand the suffering of animals. During an interview with a child psychologist—one of the first steps in his long investigation—Setz has what can only be described as an empathy attack:

She held the open book toward me. The picture showed a monkey in a box. The face contorted with pain. I turned away, held a hand out defensively, and said:

—No, thank you, please don’t.

She looked at me in surprise . . . I held on to the seat of my chair. [My wife] Julia had advised me in moments of sudden fear to focus all my attention on something from the past.

Setz’s attacks are numerous throughout the novel, whether they are crippling him as he delves deeper into the Helianau relocation mystery, or whether they’re simply recounted from the past during his brief career at the institute. In fact it’s an attack of empathy that leads Robert to remember Setz. During his first class, the new math tutor’s credibility is undermined by a photocopied magazine article left on his desk: “A picture showed a bee whose backside was destroyed. I read the caption. Bees don’t always die after they have used their stinger in defense. This bee lived for seven hours without its stinger.” Unable to maintain composure, Setz flees the lecture hall. It isn’t long before Setz, as he observes the way the students interact—including a form of bullying in which boys enter one another’s proximity circles to try to get each other to vomit—begins to view the students themselves as strange, helpless animals; especially the relocated students, who simply vanish from their rooms. Again, Dr. Rudolph warns against getting involved, against feeling too much. They are, after all, he explains,

children with limited social options . . . Truly remarkable and mind-boggling what situations human beings [can] come to terms with. We could even live deep inside the earth . . . in completely lightless circumstances, in areas with contaminated air and poisonous water, at polar stations in eternal ice, or in monasteries thousands of feet above sea level, where the oxygen content of the air was so low that everyone turned to God.

—Yes, eventually people will adapt against anything, said Dr. Rudolph.

Setz, however, cannot turn a blind eye to what he perceives as suffering. It should be said that the children’s preferred term, when suffering one another’s proximity, is to endure. “I’m enduring it!” shouts one student as he refuses to leave Robert’s dorm, as he reaches out to caress his skin. I’m enduring you, is what he means. That same student is soon after relocated and never mentioned again, one of many that Setz, years afterward, tries to track down. To endure—it’s hard to think of a more succinct synonym for love. Even the word compassion, at its twin Latin roots, translates to something like “to suffer with” or “to suffer together.”

Robert, too, has a strange relationship with animal suffering. Unlike Setz, Robert finds these images of pain, these stories of endurance, to be soothing. “Why was that so much more comforting than all the prayers and religious maxims he had heard in his life?” he wonders. At the Helianau Institute, Robert’s biology teacher feeds him “relevant material,” such as:

the story of Mike the chicken, who survived for a year and a half without a head, was fed by his owner with a dropper, and each morning, in a futile attempt to crow, squeezed air out of his open throat. With the story of the two-headed dog created by a Soviet scientist; of the transplanted head of a monkey that survived for several hours and asked for water by pushing out his upper lip in a gesture he had rehearsed beforehand . . . Of the peculiar coot that had been owned by a Russian noble and exclusively laid eggs with already-petrified, mummified chicks.

That Robert finds transcendence in the pain of defenseless creatures while Setz finds horror does not set the two men in opposition. In fact, when Setz admits that “Ever since I was a child, my sympathy with things and animals had been stronger than with people,” one can easily apply the same confession to Robert, who’s almost autistic in his dealings with other people and delights in making them uncomfortable. “You poor thing,” Setz seems to say, where Robert might only nod. Where Setz imagines the creature’s suffering, Robert understands he cannot perceive it. He knows that to suffer is to endure, and he takes comfort in proof that others can endure.

As a metaphor for aloneness and loneliness, it’s difficult to beat the eponymous Indigo sickness, an innate condition that precludes contact with others, that demands literal space between you and the next-closest person. So too does Setz the author imagine, beautifully, the way these children endure—their unique mixture of shouting and hand signals, their spatial awareness of those around them, their way of moving in sync like schools of fish or flocks of birds. What Indigo children first learn to endure is their innate aloneness, the hugeness of their own voice and imagination versus the literal distance of the people around them, not to mention the limited influence of their parents, teachers, and (if they have them) friends. With so much self in their lives, they get to know themselves. Yet the Indigo condition begins to fade with adolescence, an age where aloneness transforms into loneliness, and the children must learn to endure something far more challenging: proximity to another person, or what most call intimacy.

With all its puzzle pieces and mute sadness, Indigo begins to mirror the narrator Setz’s own hope for a pattern in the suffering, for order and justice. In the future sections of the novel, centered on Robert, the ex-tutor Setz is a broken, stuttering, nervous ruin of a human being, and yet still he obsesses over his red-checkered folder, feeding it as much information as he can find, while—in a green folder—he attempts to build a narrative around his search for the relocated children. Here the shady organizations, nefarious individuals, and corpora-military acronyms multiply, leading Setz further into the dark. “As soon as we discover a new animal,” he observes, “the first thing we’re interested in is the question of whether we can eat it. And with us it’s exactly the same. When a baby is born, people start thinking: What might it be good for? In what way might it serve me?” However brutal—however inhuman—all he wants is for there to be a reason, an excuse for all this pain. Indigo children exist, he wants to prove, for a reason; Setz himself, he hopes, exists for a reason. He cannot bring himself to understand that there may very well be nothing to understand.

All this ought to be a juggling act that should lead to an unreadable disaster of a novel, yet Indigo is crystalline in its clarity, hilarious and terrifying and deeply sad all at once, often in the same sentence. So too is Ross Benjamin’s translation a marvel, keeping the author Setz’s puns intact and his metaphors sharply, beautifully mundane: “Robert walked toward a bright restroom symbol at the end of a corridor. Here a fluorescent tube, probably years ago, had gone mad with loneliness. It flickered and buzzed in an incomprehensible medley of Morse signals, an erratic eyelid twitch. It had waited so long for someone to finally stand under it, and now everything pent up in it burst out at once.” One would think that Setz’s boyish penchant for absurdity and grandiose delusion, for indulging in Pynchonian scheming and Nabokovian wit, would preclude Indigo as novelistic art; but in fact it's these qualities and more that give it its life—because life is absurd and delusional, full of lies and confusion and moments so frustrating and cruel you can only laugh, else you’d collapse in despair. As with the best of novels, one can safely, sadly say, “It’s all here.”

Patrick Nathan's fiction and essays have appeared in Boulevard, the Los Angeles Review of Books, dislocate, Revolver, Full Stop, and elsewhere. He lives in Minneapolis.