The African Shore

by Rodrigo Rey Rosa

Translated by Jeffrey Gray

(Yale University Press, 2013)

Severina

by Rodrigo Rey Rosa

Translated by Chris Andrews

(Yale University Press, 2014)

Reviewed by Jennifer Kurdyla

“Books are quivering, murmuring creatures”: so observes the bookshop-owner protagonist of Guatemalan writer Rodrigo Rey Rosa’s most recent work of fiction, Severina. This unnamed narrator’s love for his profession is every bit as apparent as his lust for the mysterious young woman he will chase over the course of the novella. His observation, incidentally, is a succinct and poetic tagline for the author’s view of the creative process. Rey Rosa has in recent years taken up the charge of carrying on the literary legacy of his groundbreaking Latin-American predecessors—García Márquez, Borges—who are also his major influences: the idea of a world governed by coincidence and chance, and the ability of books to somehow contain and shape those experiences that are, in fact, more like dreams. Just as much as he deems it an “accident” for him to be Guatemalan, as he told Francisco Goldman in an interview in BOMB, and thereby exposed to that country’s horrific, violent history, Rey Rosa uses his characters to navigate a series of accidents and collisions that ultimately inform their mutable and uncertain identities.

The Spanish publication of Severina in 2011 marked Rey Rosa’s return, after a twelve-year hiatus, to writing; his last publication had been La orilla africana (The African Shore) in 1999. Over the course of his career, he’s enjoyed a privileged translation treatment from his friend and mentor, Paul Bowles, who first ushered his work into English in 1985. Bowles died in 1999, and these two works published since then have only recently appeared in English, respectively translated by Chris Andrews in 2014 and Jeffrey Gray in 2013. But even without the direct influence of Bowles, a fellow expatriate and sponge of disparate cultures, Rey Rosa’s newest work maintains its understated urgency that has made him, in the words of Roberto Bolaño, “the most rigorous writer of my generation, the most transparent, the one who knows best how to weave his stories, and the most luminous of all.”

Although Severina and The African Shore differ in myriad and important ways—from setting to structure, from psychological impetus to type of interpersonal conflict—reading them in juxtaposition presents Rey Rosa’s chameleon-like identity in high relief. One might be tempted to call him an embodiment of Keats’s negative capability: in both books, characters are faced with explicit losses and recreations of identity (lack of ID card, names withheld and stolen, mistaken ethnicities, etc.), and he is capable of shifting between narrative tones even as diaphanous poetry animates the brutally violent prose. Take, for example, the line “The clear African noon struck his eyes as if two fingers had jabbed through them all the way to the back of his head”—an image made beautiful through its assault of precision. But Rey Rosa also deliberately manipulates the circumstances of identity rather than transcending or eschewing them. As one sees in the work of Kafka, Borges, Camus, and Nabokov, the details of our existence are game pieces designed to be moved and usurped by other pieces, even if those moves are not premeditated. These actions, rather than the reason or motivation for them, are the subjects of Rey Rosa’s fictional labyrinths.

* * *

“I’m constantly waiting for things to write about . . . It’s a way of seeing the world that makes you more sensitive to coincidences, which aren’t supernatural—life is just very complex and strange. Inexplicable things are always happening.” –Rodrigo Rey Rosa

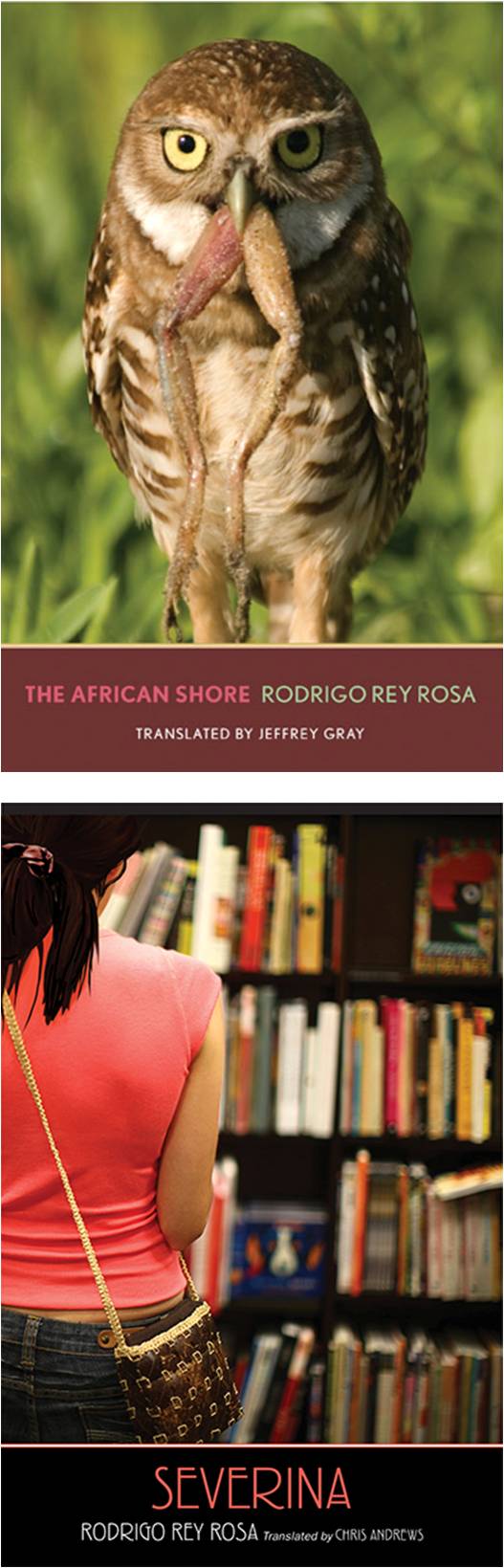

In The African Shore, Rey Rosa illustrates these motifs through the intersection of three individuals differentiated by their varying degrees of self-awareness. We are first introduced to Hamsa, a teenage Muslim orphan working as a shepherd in Tangier. Diving into the water to save a lamb from his flock, he falls ill and convalesces at his grandparents’ home. He happens upon an injured owl perched in their garden, and after deliberation over a pipe of kif decides “it was a good idea to catch an owl and pull out its eyes. Some people boiled the eyes in water and ate them, or you could make an amulet with one of the eyes and wear it on your chest to keep off sleep.” Hamsa, in this unquestioning trust of his local folklore, religion, and customs (he’s smoked kif since he was a boy), possesses the most self-assured identity in the novella: both a Moroccan citizen, and one of few characters in Rey Rosa’s book whose name we know at full disclosure along with his family history and personality. But it’s because of this more straightforward expression of identity that he cannot carry the story alone: indeed, it’s thanks to coincidence that another belief that owls are bad luck—and their capture equally so—arrives to upend that familiar stability.

The strangely appropriate cover art of the Yale edition of The African Shore captures in an image how such individuality is challenged in the remainder of the book. Just as we see an indifferent owl half-swallowing a frog outside the text, the owl inside the text comes to represent the kind of transient, ingestive existence the book projects as real. It even perhaps serves as a fulcrum to introduce us to the second main plot, as the owl’s fate traces an inverse trajectory from that of the book’s third character, an unnamed visitor from Colombia. This visitor’s disoriented entrance into the novella—he’s the one who has his eyes pierced out by the sun, waking up in a pensión after a forgotten night out—follows him throughout his stay. Lacking a name or clear ethnicity—he’s mistaken for Moroccan on several occasions—he floats through the city with the same passive objectivity that we’re expected to assume as readers, viewing familiar-yet-unfamiliar faces whose “features [have been] brought together by chance as in a book of sketches by a prolific and careless artist.” This man is on his way to recover his missing passport when he buys the owl from a poor boy in the market, initiating a dramatic pursuit of the man by the police given his lack of paperwork and suspicious companion; it’s even more suspect, as the Colombian consulate remarks, since in Colombia, these birds are bad luck.

It would be easy for the man to let go of the owl, deemed even more worthless due to its broken wing, but this story, like Rey Rosa’s other novellas, does not obey logic or reason. Instead, the happenstance of their meeting at the market makes their union germane for each of them, and for the book. Rey Rosa even confessed how such coincidences shaped the book on a global, structural level to translator Jeffrey Gray, explaining that he'd only fit Hamsa’s and the Colombian’s narratives together, like a puzzle, once the need for narrative coherence arose. With the owl in tow, we move back in time to learn of this man’s life back at home; an epistolary section called “Necklace” within Part Two comprises his correspondence with his wife, Laura, whose salutations to him grow less and less genuine (from “My dear love” to “Hello!” and “Hi my love”) as she expresses concerns that he’s fled the country to sell drugs. Just when we feel all of our assumed knowledge of this man is wrong, our grasp of his persona loosening with every page, the owl provides the needed release. They both take flight in the novella’s third part, also titled “Flight.” While waiting at the airport, the Colombian is finally revealed to be Ángel Tejedor, and is killed by a man who utters the name in an unknown accent. Seven months later, we are back with the owl and Hamsa. The owl is given a name, Sarsara, by the man who cures his broken wing; “Sarsara,” although never explicated in the text, translates in Arabic to “furious wind,” and it seems that through this embrace by language, even more than its physical rehabilitation, the owl ultimately gains its freedom. As Sarsara flies out the window, he’s recalling with ironic humanity its suffering while trapped as it flies off into an alcove. Liberated from the uncertainty of the past by their names, the man and owl join together in a strange, nonsensical harmony that attests to the value—the need, even—for the kind of traumatic dislocation they’ve both experienced in the course of the book in establishing any sense of self. It becomes the arbitrary rationale for the book set in and titled after a place that is not Rey Rosa’s own: “On the Tangier side, thousands of swallows were taking flight in a block against the huge screen of the sky, each one a point in a net that was changing its form, weaving and unweaving at the whim of some natural intelligence.”

As rich as it is in implied meaning, and even considering Rey Rosa’s penchant for elliptical plots, the owl’s physical movement within the final part of the book is, frankly, rather abrupt and confusing. But in stepping back from the text to its context—that of its author’s life—the final scene seems less arbitrary than it does at first glance. Rey Rosa was writing this just before the death, at age 88, of his long-time mentor and translator Paul Bowles. A prolific and influential expatriate, he excelled in every corner of the Modernist world from music (opera and Moroccan folk music alike) to literature to translations. The pair met in Tangier, where Bowles spent most of his life after leaving the U.S., and Rey Rosa told Goldman that the book was a “farewell” to that city—and, we might add, to the person who made Tangier Rey Rosa’s most formative escape from his war-torn homeland. He further claimed that his and Bowles’s common ground was in writing “tales of violence,” and although lacking any mention of war save a mention of Chilean dictator Pinochet, The African Shore pulsates with an evoked undercurrent of imminent violence, even if it’s reduced to the individual level present in the book’s language. Through the owl, then, Rey Rosa is able to channel his own multiple flights during his life, and translate the memory of his translator into writing.

* * *

“Reality is not always probable, or likely.” –Jorge Luis Borges

The correlation between books and life is even clearer in Severina, a still slimmer novella than The African Shore that takes place largely in a bookshop. The owner of La Entretenida (which is Spanish for “entertainment”) is overwhelmed by desire for a young woman who starts attending the store’s poetry readings, slipping into her purse a few volumes off the shelves with each visit. The thievery infuriates him, yet he also lets his “bookish impulse carry me beyond the bounds of reason” toward obsession. As months pass, he winds up taking care of the woman’s dying grandfather, Señor Blanco. When Blanco finally passes away, the narrator, the woman, and his friend, Ahmed, carry the corpse to be buried illegally. Their relationship ends when she and Ahmed flee with a number of valuable books from the shop, including a set of forged letters by Borges they expect will pass as authentic to less experienced collectors.

As translator Chris Andrews explains, Severina differs from most of Rey Rosa’s work in that it uses characters’ desires, rather than their fears (viz. the owl), to propel conflict: the narrator’s desire for genuine love, the woman’s desire for illicit objects. Attaining both of these requires, not surprisingly, an erasure of personal identity. The woman is the eponymous Severina, who favors this surname over her first name, Ana, which means “I” in Spanish. She fails to coalesce into a full being even by the book’s end. She never holds an ID card and boasts of a “special freedom” because she understands how people are conditioned by lies from childhood: Santa Claus, “universal love [and] democracy.” The narrator understands that her being is illusory yet loves her anyway. There’s no explanation for any of this, even from their first encounters when the narrator admits “Why was I so sure she’d be back? I wondered. I didn’t know.” What they do know is books; they find the greatest enjoyment in reading together the collected works of Borges, the content of which mirrors their own unstable, irrational selves. Furthermore, as traders of books they have an understanding of their self-worth as vessels—texts—that gain value only if someone says they’re real, regardless of that claim being true or not. Whether it’s a book in translation or written by a false hand, or a body with a soul one moment and without in the next, everything is subject to the same possibility of being stolen and taken away. It’s a very Borgesian kind of life, and one that makes us want to peer deeper into Rey Rosa’s stark, clipped prose.

* * *

“In paying attention to reality, just by passing it through our filter, we change it, construct it—not necessarily with good or bad intentions. It’s inevitable,” Rey Rosa told Goldman. This statement ascribes Rey Rosa’s searching works with at once more and less of a so-called “purpose.” We read this kind of writing not necessarily to understand what did happen to his characters within their textual world, but what could happen to any of us characters off the page. Like Joyce’s fingernail-paring artist-divinity, he steps back and allows the drama to unfold without omniscience, working with the surprises and inconsistencies we find in these two works. In ignoring the pressure to abide by the rules of “reality,” and removing the subjective focus of what we think is real, he bestows upon us a similar freedom to embrace the dream-logic of the uncanny.

What greater form of fantasy could a reader ask for?

Jennifer Kurdyla is an editor at Alfred A. Knopf. She lives in New York City.