Counternarratives

by John Keene

(New Directions, June 2015)

Reviewed by Adrian Nathan West

For some time, among a small group of practitioners of what may be termed—loosely, with reservations—prose fiction, there has been a sense that the dilemmas incumbent upon the contemporary writer transcend the capacities of unalloyed imagination. This instinct animates the works of writers as apparently distinct as Édouard Levé, Marie Calloway, and W. G. Sebald. What may once have been a formalist repugnance, a longing to distinguish one’s art and sensations from the humdrum mechanics of accepted form, as epitomized in Valéry’s well-known refusal of novel-writing for his abhorrence of composing such a sentence as The Marquise went out at five o’ clock, has more recently hardened into an ethical conviction, often grounded, as in the case of Sebald, in rigorous historical research, that there is something tawdry and overweening in the impulse to approach the disasters of history, whether remote or contemporary, with historical recreations of the Sophie’s Choice stamp.

This conviction bespeaks the widening of a cleavage in narrative writing: to the one side lie the defenders of the bourgeois novel, those who believe, as Jonathan Franzen asserts, that there is a deep, unmet need for stories; to the other, those who suspect, some overtly, others more tentatively, that the innocence or guilt of stories cannot be divorced from their social and political context, and that the status accorded to creative imagination within the economy of cultural exchange does not automatically exempt it from moral scrutiny.

At issue here is a disagreement concerning the sources of written art: the proper origin of the wonder and foreboding from which artistic creation proceeds. Are they in some measure subservient to the demands of history or the present, or is the artist justified to consider himself sui generis? Might inspiration be inseparable from a kind of attunement to one’s past, so that the claim of an aboriginal imagination is no more than a smug pose? Is the rejection of any beholdenness always already deviant with respect to art’s proper vocation?

Questions of this kind hum in the background of Counternarratives, John Keene’s new collection of stories and novellas, recently published by New Directions. Counternarratives extends an intuition already present in his first book, Annotations, that the themes the author strives to bring beneath his purview might best be approached obliquely. The tales in Keene’s newest work range from the chronicle of an insurgent slave in seventeenth-century Brazil to a dreamlike recollection of a passion-filled evening between Langston Hughes and the Mexican poet Xavier Villaurrutia. No two stories are formally alike: “Gloss On the History of Roman Catholics in the Early American Republic, 1790–1825; Or the Strange History of Our Lady of the Sorrows” combines philosophical lucubrations with straightforward history and excerpts from the journal of a slave, while “Acrobatique” opens and closes with a vertical line of prose, meant to symbolize the rope from which the famed black acrobat Miss La La hung suspended, a leather bit between her teeth. What unites them all is a meticulous attention to the weight and sound of words, a sensibility more poetic than prosaic, and a measured, deliberate meditation on the texture of black lives in history, taken not in the sense of grand narrative, but of what persists in the gaps, awaiting resurrection through art.

Keene’s Counternarratives offers a corrective to the boilerplate that would forbid art from entering into the political. Its very title suggests that not only that the story has been told wrong, not only that it is not enough to tell other stories to be placed in their appropriate box (African-American, Post-Colonial) and thereby neutralized before being passed on to readers as ersatz probity while the real economic and political conditions that perpetuate injustice grind on unaffected; but rather that, for literature to continue to fulfill its vocation, the record has to be set straight. The political is not imposed on these tales from above; instead, a full account of the character’ life histories cannot be given without recourse to the political. Even their names are imbued with relations of power: In “A Letter on the Trials of the Counterreformation in New Lisbon,” an insurgent slave rebukes a Portuguese friar who addresses him by his Christian name, João Baptista:

They may baptize me a thousand times in that faith, with water or oil, no matter. The one who died was named João Baptista dos Anjos, by his own hand, and they imposed his name on me as a penalty because he took his life, though that is another matter. I would nevertheless ask that you call me Burunbana, as that is my name.

Freedom from a political conception of life is seen not as the natural condition of life, but as an effect of intimacy with power, of belonging to the victorious side of history. Yet this programmatic enterprise is anything but vehement: Keene is not out to teach lessons, but to evince, by the poignancy of the anecdotes he shares and his formal and linguistic ingenuity, the grandeur and sorrow of voices from the past whose experience continues to inform the present.

The axis of these tales is not so much slavery as the constitution of the black subject as an entity especially suited to subservience and degradation, fit for exclusion from the fields of speculation and experience proper to its white counterparts. In “Cold,” the brilliant composer Bob Cole, tormented by a success won at the expense of his own people’s dignity, drowns himself in a river in the Catskills; in “Persons and Places,” W.E.B. Du Bois walks past his tutor, George Santayana, yearning for a moment of recognition of common humanity from a man who would reserve not a single word for the author of The Souls of Black Folk in his celebrated autobiography; and in “The Aeronauts,” one of the volume’s most delicate and affecting stories, a gifted waiter at Philadelphia’s Academy of Natural Sciences, pondering the lengths to which his prodigious memory might take him, recalls his father’s admonition: “[W]hat sort of life you think there is for us if our heads stay too far up in them clouds?”

For many readers, the centerpiece of Counternarratives will be “Rivers,” a first-person testimony by Miss Watson’s Jim, the escaped slave from Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, concerning the fate of his erstwhile companions. In a chance meeting on a St. Louis street, where the emancipated Jim is now a tavern owner, Tom Sawyer chides the narrator for his failure to step aside when he sees two “gentlemen” approaching. Jim’s eyes glaze over as Tom boasts of his two years at university, his employment at a law office arranged by Judge Thatcher, and his thought of moving to New Orleans upon his admission to the bar. Readers of Twain may recollect that his greatest novel opens with Tom trying to convince Huck to tie Jim up as a joke; and the increasing surliness of Tom’s comments insinuate the ease with which the petty cruelties of youthful pranks may later grade into the overt violence by which racial hegemony is maintained and defended. Huck remains reticent and slightly sullen throughout: after a brief account of his dustups in Kansas, he says, “But I don’t think old Jim wants to be bothered with hearing about any of that.” An outcast, the son of the town drunk, he has not forgotten his decision to go to Hell, if need be, in order to rescue his friend from slave-catchers. Later, while Tom presumably whiles away the war in safety, Huck and Jim meet once more on the field of battle.

Throughout the book, Keene plays with the possibilities of his title: Counternarratives serves as the heading for the first group of stories, Encounternarratives the second. The final section, Counternarrative, implies a more conceptual approach—the opposition to narrative, or the narrative that exists solely by opposition. It consists of a single story, Lions. In a conversation between a dictator and his muffled victim, the easy continuity between ideology and demagoguery and the inexhaustible lure of corruption come to life in a cell that could equally lie in Zimbabwe, in Uganda, or in Equatorial Guinea. The two figures speak of their youthful idealism, their yen for Fanon and Amilcar Cabral; of the depraved luxury of power and rapine; of boyhood love incompatible with the struggle for dominance; of what might have been, had Africa been untouched by Western hands. With relish, the dictator’s recollections turn on the moment when he surpassed the man slumping in the chair before him and took hold of the reins of terror:

If I wanted your entire ancestral village to lie prone before me as I entered them one by one, if I wanted to raze the entire village and rape all the crushed and dismembered and burnt bodies, if I wanted to destroy every vestige of every single soul that spoke the same language as you and rape their ghosts, rape your ancestors who were my ancestors, if I want to rape the vestigial mothers and fathers of us all, if I wanted to rape the last embers of your existence and memory and then what wasn’t even left after that, I would have done so. I can write the story of reality however I see fit. At any time.

In a 1958 interview with the Paris Review, Alfred Chester, prodding Ralph Ellison about the scope of “the Negro writer,” baits him with the statement, “Then you consider your novel a purely literary work as opposed to one in the tradition of social protest.” Ellison responds that complaints about the protest novel should not be leveled against the genre as such, but rather against the ineptitude of individual examples of it. In any art that deals with human life, considerations of justice will prove inseparable from those of beauty and truth: in any aesthetic object justly rendered, these virtues will be present, and their absence is always traceable to some error in judgment, a false exaggeration of the sort common to clichés or a failure to attend on some fundamental property. Counternarratives is political fiction in the best sense of the term, with its heedfulness to the lived interstices in history and the horizons of human feeling weighed down by the ballast of oppression.

Adrian Nathan West is a writer and translator as well as a contributing editor at Asymptote. His book-length translations include works by Josef Winkler and Pere Gimferrer as well as The Art of Flying, Antonio Altarriba's graphic novel about the Spanish Civil War. His first novel, The Aesthetics of Degradation, is forthcoming from Repeater Books. He lives between Spain and the United States with the cinema critic Beatriz Leal Riesco.

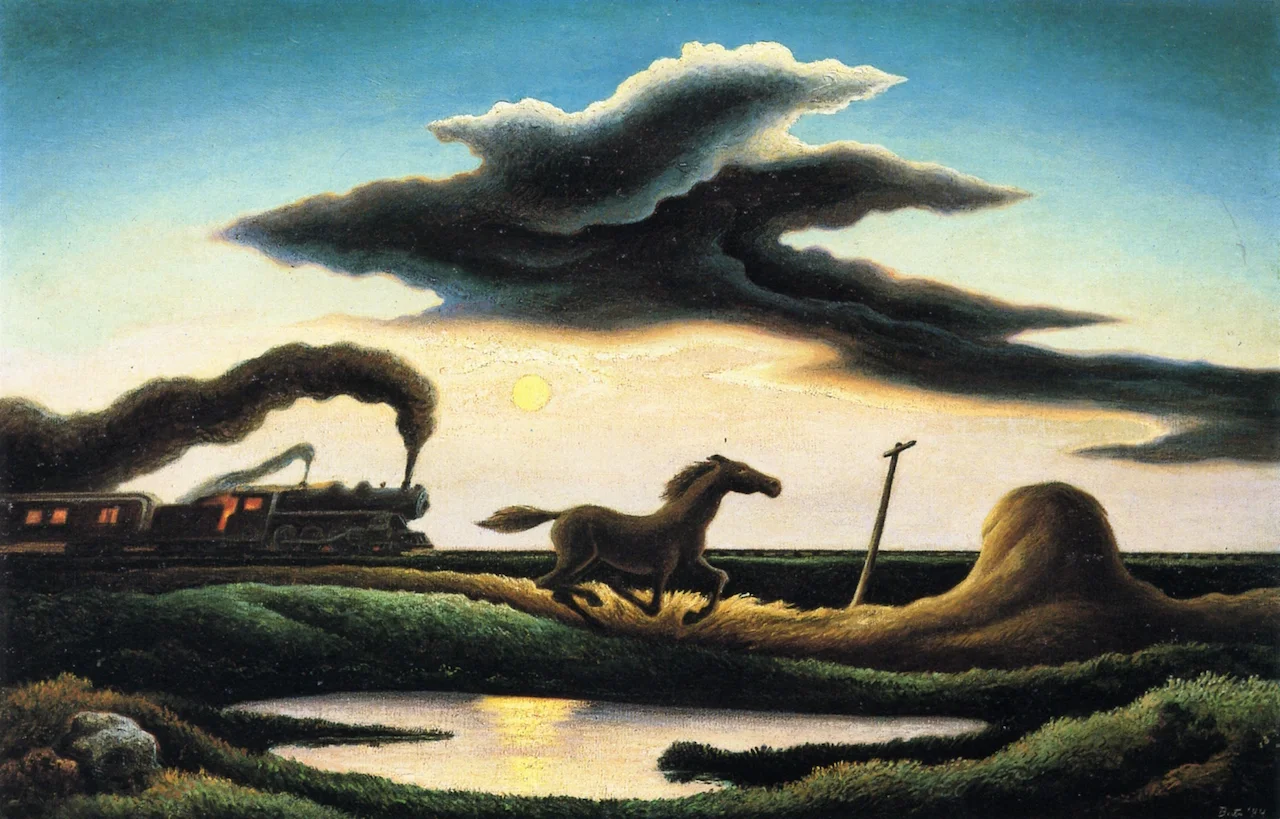

Banner image: Thomas Hart Benton's Homeward Bound