Henri Duchemin and His Shadows

by Emmanuel Bove

trans. Alyson Waters

(NYRB Classics, July 2015)

Reviewed by John Knight

Almost all of Emmanuel Bove’s work has been forgotten: twenty-eight novels under his own name, a few more under pseudonyms, many magazine pieces, a variety of short stories, and a meticulous if sporadic diary that reads almost like a manifesto of artistic solitude. This oblivion stings all the more for Bove’s having been immensely popular during his three-decade career—roughly between 1918 and 1945—when he wrote devastatingly concise and piquant odes to the consuming anxieties characteristic of the interwar years in France. About half of his work has been translated into English, much of it already out of print, but with this most recent publication from NYRB, Alyson Waters’s acute translation of Henri Duchemin and His Shadows, it suddenly seems as though we have a key into the novels, which might even provoke renewed, and certainly warranted, attention for this quiet and quietly forgotten writer.

Because Bove was a novelist, first and foremost, Henri Duchemin—a collection of seven stories—appears to be an unusual angle of approach. However, they have at their heart a familiar Bovian subject. These are the stories of fragile young men in France, mostly Paris, who suffer excruciating psychological pains at the whims of the world. They vary slightly in temperament and circumstance, but almost universally they are poor and lonely. Bove appears to have no shorage of this sort of character and these young men careen across all of his work, substantiating his reputation as a master of “impoverished solitude.” Almost every tale—both in these stories and his novels—begins in unremarkable circumstances and proceeds to spiral downwards, as the stability of the protagonist’s psyche is slowly fractured by the people around him. These are the works of paranoia and malaise, of desire for meaningful relationships and simultaneous repulsion at the very same idea. It’s tempting, therefore, to neatly file away Bove’s work as a minor French writer in the second quarter of the twentieth century who paved the way for the works of Jean Paul Sartre (himself, in fact, a fan). But in turning away from his longer works and towards the specificity of these seven stories, we find something of a map or perhaps dreamlike visions of the psychologies, tempers, and fragilities of the Bovian man. A bit more than character studies and slightly less than robust novellas, these tales are portraits of unstable coal-like lumps of anxiety that are being squeezed and cooked into diamonds of despair right in front of your eyes.

All the deeply French protagonists in this collection—including Henri Duchemin, Monsieur Baton, and Robert Marjanne—suffer a variety of paranoias stemming from some sort of interpersonal relationship. Sometimes these relationships actually exist, and sometimes they are only possibilities, but either way these men are obsessively sensitive to the extension of themselves in the world, and nervous—beyond nervous, really—about how to handle it. For examples, at one point Baton is invited to lunch, “a small thing” but an invitation that “filled me with joy.” But in the following sentence, he backtracks: “Unfortunately, I never have the courage to accept what is offered to me. I’m always afraid of accepting too quickly.” He’s not exactly incapable of action here, but is momentarily overwhelmed by what it means to other people, and therefore to him, if he accepts. Bove’s characters certainly participate in the world (frequently with the kind of painful awkwardness of a overwrought personalities), but they are forever second-guessing themselves. With a little prodding, Baton accepts the lunch offer. “Yes—I had said yes. If only you knew how difficult it is for me to say yes…It seems to me that yes means freedom, happiness.”

Though saying yes might be an act of freedom (in this case a freeing of Baton from himself), it doesn’t mean happiness. The dichotomy between freedom and happiness is a persistent concern in these stories and Bove’s other work, as if he were forever poking holes in the received wisdom that autonomy is good. This lunch turns out to be the first in a series of events that lead to Baton’s painful loss of a “friend,” made all the more painful by the interior horrors of actually making all the choices at each juncture. On the other hand, there are just as many instances of Bove’s characters suffering for want of their freedom. His novel Quicksand, for instance, details the sad saga of Joseph Bridet who, try as he might, can’t escape the clutches of Vichy France. In “Night Visit,” Paul’s wife leaves him, which ruins his life not so much because of his loss, but for his complete inability to do anything about it.

When choice is paralyzing and no choice is equally crushing, Bove’s characters are reduced to the mere facts of their lives and their standing in the eyes of others. Like Bove, most of these men served in the first World War and are either collecting pensions or journalists or both and are therefore overwhelmingly poor. They agonize over this fact, not so much for the discomfort it brings them, but for how other people consequently perceive them. They all desperately want to be liked, and the only one who doesn’t is considered “mad.” As such, they suffer a tumultuous inner dialogue as they attempt to navigate the gap between themselves and their acquaintances who are, regardless of intimacy and longevity, ultimately strangers.

In contrast to his characters’ overflowing anxieties, Bove’s sentences are short, direct, and so sparing in detail that when a description surfaces or an emotion spills out, it flutters like a flag against the sky—silent but unmistakable. They catch your attention not so much because of the sentiment’s originality, but because it feels like you’ve been let in on a secret. And in this way Bove’s stories remain taut, stretched like a tightrope across an otherwise gaping void. On one side stands the plot of the novel, and on the other are the most intimate thoughts of the protagonist, and Bove is forever scurrying back and forth between them, chronicling a series of events punctuated by ruthless self-scrutiny.

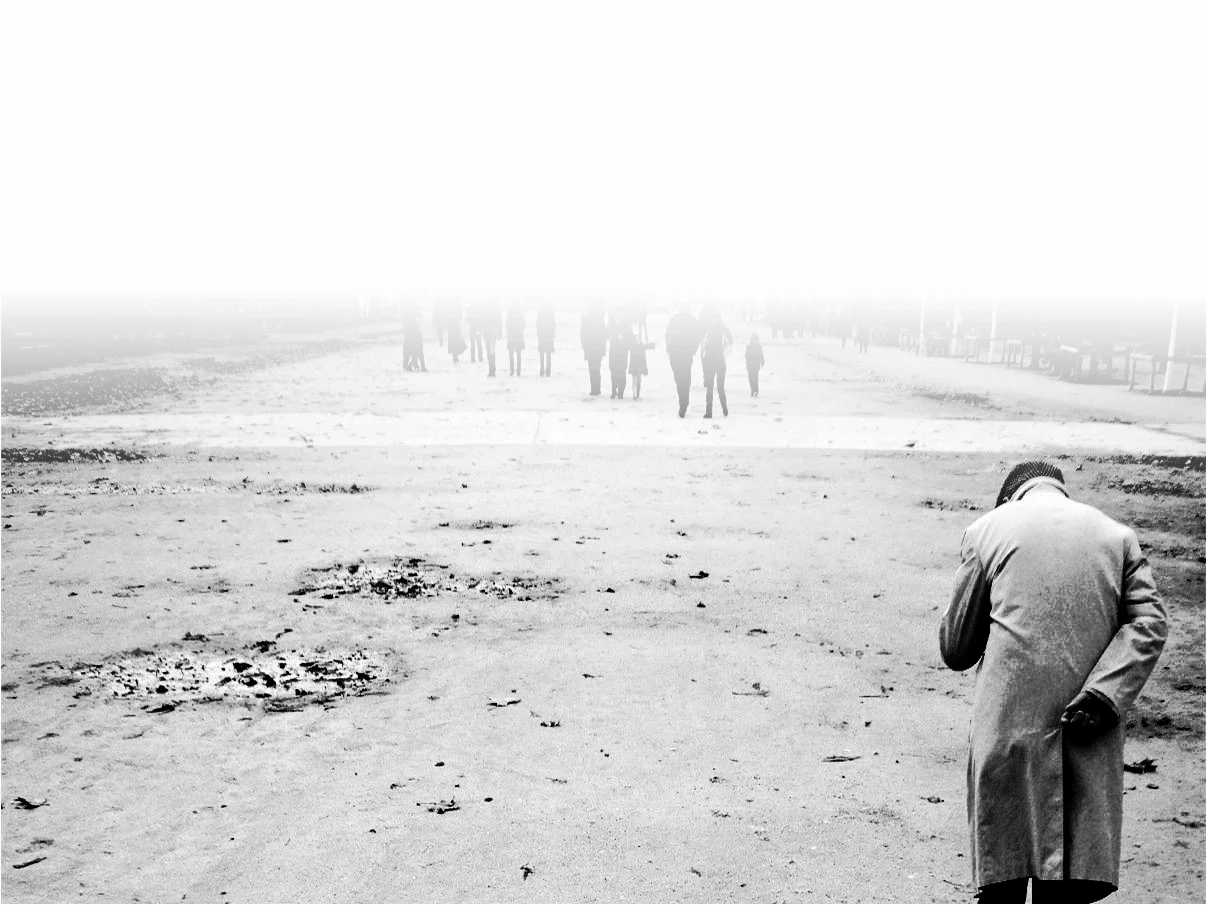

Usually a Bove story begins with the protagonist somehow removed from the world, usually by solitude, but also by poverty, paranoia, depression, and—in his later novels—state rule. These characters wander, slide uncomfortably into bars, drink coffee, strike up conversations, get arrested, and generally meander through 1920s and ’30s France, doing their best to fit the demands of the world into those of their fragile selves. Usually these two competing demands are too much, and the protagonist ends up, in one way or another, buried.

The namesake of this slim collection is, naturally, the most exemplary of this sort. When we meet Henri Duchemin, he is sitting at a pub in Paris on Christmas Eve. He is poor, and uncomfortable, wishing to go home but despising the state of his wretched lodgings. As he debates what to do, a beggar comes in asking for a kindness, and is quickly kicked to the curb by the barmaid. The other patrons enjoy a brief camaraderie over the incident, but Henri “sensed that these strangers were harboring unkind thoughts.” He leaves.

Before going home, Henri ducks into a café for a hot cup of coffee. He sits next to a woman who strikes up a conversation—“What a sad Christmas Eve!”—and Henri responds in kind, and then offers to tell this stranger the story of his life, “a very sad story.” At the thought of this exchange, of the very possibility of a shared confidence, Henri is filled with joy. “He was so happy to be speaking that he seemed to be younger. He was sure he would be liked and this gave him confidence.” But just before he is about to continue on, the woman bursts out laughing. “Don’t be ridiculous,” she says. “If you’re so unhappy, just kill yourself.”

This is a crucial moment for Henri, and a moment representative of a disturbing undercurrent throughout Bove’s work. Bove was a master of suffering. His curt sentences convey the misery of consciousness with the kind of confidence that can only arise from someone familiar with the mind’s doldrums. Most of the time, his characters are looking for some escape, some kind of salvation, either from themselves or from a situation they are incapable of controlling. And the question looms repeatedly: why don’t they just kill themselves? Oddly, Bove doesn’t seem to consider it the answer to desperate despair—his novels certainly don’t advocate suicide—but rather a choice that, if made, is at once the most affirming and the most contradictory manifestation of an individual’s autonomy. “Kill myself? She’s out of her mind,” Henri thinks to himself. “The world is so cruel.”

Henri returns home where he finds his lodgings in disorder, and decides not to kill himself because even a forty-year-old man still has plenty of time to get rich. Money, he thinks, ought to save him. He falls asleep in his chair and dreams that his landlady comes with a noose and encourages him to take his own life. He demurs, again, and instead trudges out into the world where he meets a man who tells him of a banker that he, Henri, can murder for his riches. Henri tries to avoid the crime, but in a delightful bit of dream logic eventually ends up at the banker’s house with a bloody hammer in hand and stuffed wallet in his pocket. He then flails about the city for the rest of the night—giving away money to a bevvy of card-playing strangers, asking to be loved by a woman he meets at a café, and generally wandering through his thoughts.

The parallels between Henri and the Underground Man are strong, though they differ in two ways that are important to Bove’s work. (And without question, Dostoyevsky was a prominent influence—another new translation of Bove, forthcoming from Red Dust this fall, is even titled A Raskolnikoff.) The first is that unlike Dostoyevsky’s tortured soul, Henri does not actually commit a murder; he only dreams it. The second, which may in part arise from the fact that Bove is recounting only a dream, is that during Henri’s wanderings, he is not consumed so much by the moral implications of what he has “done,” but by the way that his “act” will position him in the eyes of other people. As he weighs the various options open to him in the wake of his crime, any moral scruples give way to the opinions others will have of him if he is found out:

No, he would not turn himself in. It was better to remain free, for those heartless people would never understand the reasons behind his crime. Indeed, no one would understand them. He would have been happier among madmen in whose company he would have skipped, laughed, and sun.

Henri isn’t quite mad, but he knows in whose company he would be happy, and this—more than riches or the moral state of his soul—is what matters.

As Henri wanders, and as we encounter the other characters in these stories, it is hard not to wonder at the origins of their agonized deliberations. For the most part, these characters begin with something approaching a stable mind. As the stories progress and the world makes demands, the protagonists respond with an increasingly fragile constitution in ways that aren’t necessarily wrong, but don’t seem particularly wise either. Bove lets the world slowly tighten its grip on his heroes until they become martyrs in their own unknown or forgotten or overlooked ways. It is as if Bove believed in a kind of reversed subjectivity: that the individual is so vulnerable that the external world—and particularly other people—end up determining a person’s happiness, success, interiority, and peace. The problem, or rather agony, arises from Bove’s characters’ recognition of this helpless fact.

Personal redemption, as well as utter betrayal, always appears in Bove’s work in the form of another person. Call it friendship or love or loyalty, Bove held other people aloft on a pedestal of salvation. Naturally, this is also the relationship that usually fails. As his stories churn towards their inevitable end, Bove lets happiness slip from his protagonists’ grasps while they helplessly flail to recover. At times, Bove’s insistent focus on characters anxious about being scrutinized by everyone else can make his work feel both simplistic and even repetitive. Again and again we are faced with nervous men desperate to be loved in one way or another. Monsieur Baton, for example, is taken under the wing of a rich eccentric who brings him to his house (after that fateful lunch) and visits with him on Saturdays. Baton is overjoyed: “For the first time in years, I had the impression that at long last I had a friend.” But the rich eccentric turns out just to like helping poor men, and Baton realizes he is only one among many. In disgust and with a sense of betrayal he turns back to his solitary life. “Have you noticed how often we are wrong about people?” he bemoans. In the story of the wifeless Paul, the narrator is his friend’s sympathetic ear, and possibly prevents a suicide by offering to spend the night together. In “The Story of a Madman” the protagonist has been deemed “mad” because he has deliberately cut himself off from everyone in his life—his loving wife, doting parents, longtime best friend—and heads off to drown himself. They might plague us with anxiety and constant self-doubt, but Bove seems to genuinely believe that without other people, there isn’t much left for us.

Perhaps Bove’s best-known work is his novel My Friends, which Colette helped him publish in 1922 and established him in Parisian literary scene. It chronicles much of the same ordeals as “Another Friend” (as if this story was cut from the novel, or an early sketch thereof), following a young man of the same name as he makes various “friends,” none of whom would actually qualify as a friend unless one was desperately lonely. With this and other early works, particularly Armand, Bove became one of France’s more popular novelists until the German occupation. In its wake, France suffered various economic extremes and political unease, particularly as a result of the depression in 1931. Novels steeped in the realism of the repressed individual resonated. Bove’s exemplary probing of the self-conscious man of little striving and failing to assert himself in the world fit well into the early existential fervor exemplified by writers like Andre Gide. But after the horrors of WWII, when France was in desperate need of new heroes and a new national identity, Bove’s novels of timid young men didn’t quite fit the bill. Bove died in 1945 from malaria, exactly a year after the liberation of France and two months after VE Day, but before he could contribute to another “new genre.” He had refused to publish during the German occupation, and his novels that were rushed into print after the war only go so far as to amend his concern with poverty by incorporating an intrusive and evil totalitarianism. In the best of these, Quicksand, but in others from this time as well—Night Departure and A Singular Man—paranoia usurps loneliness, and the irreparable gap between strangers which provokes suffering occurs with more references to “fellow countryman” and largely by means of impersonal state bureaucracy, rather than individual selfishness.

But the stories of Henri Duchemin and His Shadows are rooted in Bove’s most genuine concerns. In “Night Crime,” the evening ends when Henri meets an old wise man who accuses him of the murder and proclaims that Henri must suffer for the rest of his life in order to redeem himself.

Suddenly an infinite elation entered Henri Duchemin’s soul. A beautiful vision replaced the sordid walls that surrounded him. . . . ‘Yes, I have killed, but I shall suffer, suffer my entire life. I shall redeem myself. I shall be forgiven. I will do everything. I’ll endure anything to be forgiven. Oh, to be forgiven! I shall be so happy. I shall suffer, my entire life.

There are two places where Bove leaves his characters. Either they find themselves, as Henri does, fated to a life of suffering and solitude, or they die, either by their own hands like the Madman or at the hands of the world like Joseph Bridet, the martyr and patriot. Neither of these resolutions ever come as a surprise, but the pleasure of Bove is in watching the inevitable end slowly making itself inevitable. We so rarely realize how we are precipitating the events that eventually come to pass, and Bove’s great skill is to show his unsuspecting character’s hand as they march slowly but steadily towards their fate.

John Knight is an assistant editor at Farrar, Straus and Giroux.