GONERIL Hear me, my lord.

What need you five-and-twenty, ten, or five,

To follow in a house where twice so many

Have a command to tend you?

REGAN What need one?

LEAR O, reason not the need!

From its opening exchange, in which Kent and Gloucester speculate over which of his sons-in-law the King will favor in the division of his kingdom, Shakespeare’s King Lear is a play about value: the relative worth of property, of such faculties as sight and reason, and of each human life in its “unburdened crawl toward death.” This theme pervades the riveting first scene. Lear’s desire to rank his daughters according to their love for him, cast in terms of a superlative (“Which of you shall we say doth love us most”), sets off a verbal battle in which Goneril and Regan appeal in turn to a transcendent love that lies “beyond what can be valued.” The mounting drama, and indeed even the poetic meter, comes to a screeching halt, however, when Cordelia, asked to speak, voices an alternative conception of infinite value: “Nothing, my lord.” This single word, “nothing,” upon which the entire play hinges, expresses the absence of the totality that her sisters seek to quantify. It denies their superlatives and instead reveals a lack, an emptiness that occupies the same space and serves the same function as their sham transcendences. Cordelia’s “nothing” is an antidote to all of the “somethings” to which value becomes attached when they are related. Crucially, in the second scene, Edmund, feeling unjustly undervalued as Gloucester’s bastard son, initiates the deception of his father with the same line: “Nothing, my lord.” “Nothing” denies value, relation, expression, materiality, immanence. It provides the foundation for all subsequent assaults upon Lear’s ego—his somethingness. It is the source of Cordelia’s banishment and of Gloucester’s loss of sight. More than that, for all of us who confront King Lear, it leaves a permanent stain upon the very notion of selfhood.

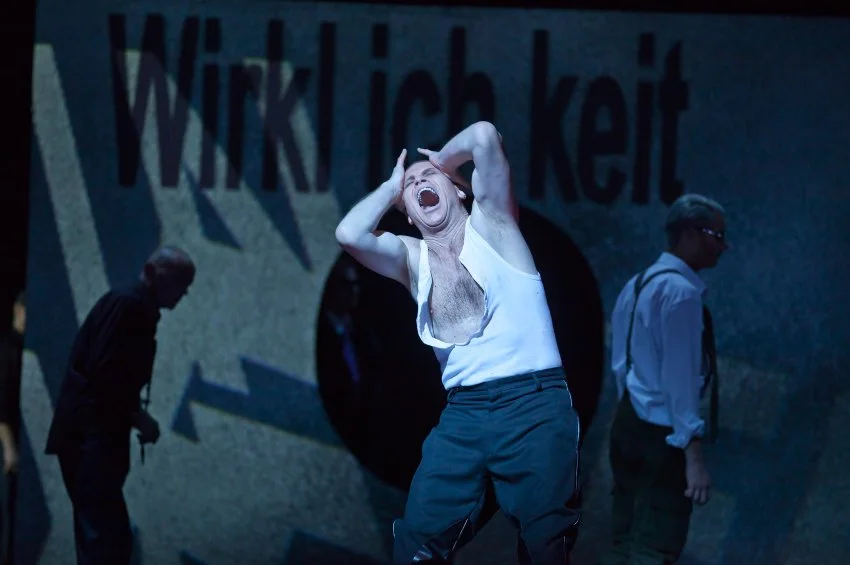

From Karoline Gruber's production of Lear, by Aribert Reimann

In his final speech, after learning of Cordelia’s death, Lear declaims the word “never” five times in a row, just as earlier in this last scene of the play (V, 3), he had uttered four times the word “no.” Especially in a play so concerned with time and aging (“oldest” and “young” serve as the backbone of the play’s final lines), “never” functions as yet another infinite value. Along with the “no,” it brings the drama full circle back to the “nothing” from which it sprang. Lear’s cry laments a dead child, but more importantly it expresses the shock of a self that once confidently occupied time and space but is now confronting the reality of emptiness and meaninglessness. His four-fold “howl,” the remaining instance of Lear’s tendency toward repetition in this scene, is the most elemental of these cries—an appeal to blunt nature, a willful denial of time and other brutal human realities: yes and no, now and then, me and you.

Two new DVD releases of 20th-century operatic adaptations of King Lear—one an established piece approaching its fortieth anniversary, the other more recent and hitherto infrequently performed—bring to mind these aspects of the play, its probing of the value of the self, its stretches towards the infinite. Operatic composers are in the business of constructing selves, and opera singers are bound to be “something,” the kind of people for whom exists the phrase “larger than life.” This has been the case since the turn of the 17th century, when Shakespeare “invented the modern human being” (to borrow from Harold Bloom); and not incidentally, Shakespeare’s career ran contemporaneous with the birth of opera, invented in Italy as a style of “metaphysical song” (to borrow from Gary Tomlinson) that expressed the distance between interior and exterior, thus lending another face to modern subjectivity and its burden of giving names and forms to the nameless and unformed. Amidst all of this striving for “something,” how might a composer tell Lear musically in a way that allows equal time and space for nothing? How might Lear, in the face of Cordelia’s challenge, musically disappear? How might an operatic character occupy the ambiguous space of the unformed with music so unrelentingly forming it?

***

Lear

by Aribert Reimann

Bo Skovhus (Lear), Hellen Kwon (Regan), Siobhan Stagg (Cordelia), Katja Pieweck (Goneril), Erwin Leder (Fool), Lauri Vasar (Gloucester), Andrew Watts (Edgar), Martin Homrich (Edmund), Jürgen Sacher (Kent)

Chorus of the Staatsoper Hamburg

Hamburg Philharmonic

Simone Young (conductor)

Karoline Gruber (director)

Marcus Richardt (video director)

(Arthaus Musik, April 2015)

Reviewed by Mark Mazullo

Aribert Reimann’s Lear, created as a vehicle for the baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, was given its premiere at the Bavarian State Opera in Munich in 1978. The opera—craggy, dissonant, firmly situated in the modernist tradition initiated by Richard Strauss in Salome and Elektra and continued in Alban Berg’s Wozzeck—has enjoyed many revivals, including productions throughout the 1980s in Paris, San Francisco, and London, and it continues to attract the attention of prominent companies. A difficult but rewarding piece, it will be performed in 2016, in different productions and with different casts, at both the Paris Opera and the Hungarian State Opera in Budapest. The first production of the opera at the State Opera in Hamburg (the company originally to have produced the premiere in the 1970s, until artistic director August Everding left for Munich, taking the commission with him) is captured on a new DVD release with Danish baritone Bo Skovhus in the title role and Simone Young conducting. The footage is from 2014 performances of a production by Karoline Gruber that premiered in 2012.

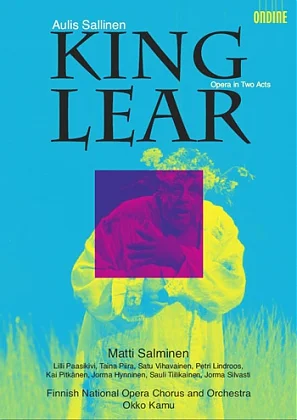

Meanwhile, Aulis Sallinen’s Kuningas Lear, composed in 1998-99, was commissioned by the Finnish National Opera, where its premiere took place in 2000, with bass Matti Salminen in the title role. The DVD release, which also features star Finnish baritone Jorma Hynninen in the role of Gloucester, comes from a series of performances at the same house in 2002. There appear to be no plans for future productions of this melodic, folksy opera, which in contrast to Reimann’s stems from the 19th-century national romantic tradition. The prominent use of celesta throughout the score recalls Tchaikovsky, and the distant trumpet fanfares that open the second act seem a musical nod to the quintessential fairy-tale line, “once upon a time.” Elsewhere, and more provocatively, the score invites comparison to a host of like-minded operatic icons of the 20th century, most obviously Benjamin Britten and Leoš Janáček, but also, in its comic-ironic moments, Dmitri Shostakovich. More gentle, straightforward, and inward than the Reimann, Sallinen’s opera makes less of an impression, which is not to say that it would be unappealing to someone seeking a more accessible style of musical-dramatic fantasy.

Questions of musical style aside, the crucial point of distinction between these two operas lies in their treatment of Shakespeare’s text. Reimann, working from a libretto by Claus H. Henneberg after a 1777 German translation of Shakespeare by Johann Joachim Eschenburg, keeps the play largely intact, while sometimes reshuffling material in order to create opportunities for such operatic mainstays as ensembles and choruses. By contrast, Sallinen, crafting his own libretto, radically reworks the play, omitting the important role of Kent, elevating the role of the Fool, and taking great liberties with several key moments in the play, such as the gouging out of Gloucester’s eyes (which is merely recounted by a trio of male messengers) and his subsequent imagined leap off the cliffs at Dover (which is interrupted by Lear’s arrival on the scene and is never executed). The modernist (but not avant-garde) Reimann, going for the jugular, seizes his dramatic opportunity by placing the horrific blinding of Gloucester front and center, at the beginning of his opera’s second part. Sallinen, whose earlier operas were invested heavily in Finnish folklore and history, transforms Lear into a more benign fairytale, one decidedly not in the gruesome vein of the Brothers Grimm.

Kuningas Lear (King Lear)

by Aulis Sallinen

Matti Salminen (Lear), Satu Vihavainen (Regan), Lilli Paasikivi (Cordelia), Taina Piira (Goneril), Aki Alamikkotervo (Fool), Jorma Hynninen (Gloucester), Sauli Tiilikainen (Edgar), Jorma Silvasti (Edmund)

Finnish National Opera Chorus & Orchestra

Okko Kamu (conductor)

Kari Heiskanen (director)

Aarno Cronvall (video director)

(Ondine, April 2015)

Such disparate approaches make for significant differences in the presentation of the titlular character. Skovhus’s Lear is at first a businessman who, in rolled-up shirtsleeves, brandishes authority with a firm jaw, intense stare, and muscular movements. Two and a half hours later, what remains of his clothes are stained and torn, his face now marked by wild shifting eyes and a moronic toothy grin. These outward changes do nothing, however, to lessen the musical torrent of his damaged ego. He remains musically the same Lear. The repeated “howls” and “nevers” in the opera’s final moments take the form of unaccompanied, extended melismas, punctuated by decisive orchestral outbursts in the sound-mass idiom that pervades the score; these are the same musical markers of the earlier, not-yet-defeated Lear. Reimann’s music is all fight; the lost self rages against fate and clings desperately to once-secure musical footings. Skovhus is impressive here, and throughout the long opera, his baritone remains secure across the wide range the score demands of it. (It would be unsportsmanlike to stress a comparison between his fine performance and that of Fischer-Dieskau, whose technically dazzling and emotionally devastating final scene is available on CD and, along with a few other excerpts from the opera’s original Munich run, on YouTube. Reimann cast one of the “nevers” as a sob: Skovhus sings an effective cry, Fischer-Dieskau renders the distinction between singing and crying superfluous.)

From the start, Sallinen imagined his Lear as a bass, thus fashioning a more muted portrait than the extroverted, perhaps even sometimes hysterical, baritone. Matti Salminen—a formidable presence known for such (typically villainous) roles as Wagner’s Hagen, Hunding, and Fafner—here mainly disavows his customary hugeness. His Lear is a fairy-tale King: his face expresses naive wonder, and his movements seem calculated not to draw attention to themselves. His clothes become torn as well, but not to any great effect. Blending into the general scheme of things, his Lear is eminently more suited to disappear. His final scene is more quietly dramatic. There is a bit of sobbing in the “nevers,” and the orchestra does build to a short climax, but the music quickly retreats back to subdued, melodic strings. This whispering Lear has little fight in him; he yields more readily to exterior forces. In this sense, Sallinen’s is the setting that more naturally suits the theme of nothingness.

The same dynamic is evident in the storm scene (“Blow, winds”) from Shakespeare’s third act. For Reimann, who surrounds it with expressive orchestral interludes, the scene becomes central to the drama. Here, Lear again resorts to melismas, while orchestral clouds thunder and flash around him. Quick fire video editing (a technique reserved exclusively for this scene) contributes effectively to the sense of disorientation. The violence abates momentarily, as the Fool and Kent enter to lead Lear to the hut in the forest; the Fool’s Sprechstimme and Kent’s unaccompanied recitative provide a respite from the sonic storm. When the orchestral chaos returns with Lear’s singing, we suspect that nature’s fury is blowing only in his head. The six-minute interlude that accompanies their entrance into the hut, which features a haunting solo for bass flute, lends great importance to this moment of profound interiority, when the three characters enter a stage labyrinth created out of multiple structures formed by the word “ich.” Sallinen’s storm, by contrast, is again more subdued, its orchestral bursts more streamlined and conventional in their textures and rhythms. Lear’s recitative, flat at first, then songlike, passes by quickly, and we soon find ourselves in the hut. In playing down the confrontation between man and nature, Sallinen all but bypasses one of Shakespeare’s iconic moments. Saying so is not to fault him for his choices, but rather to point toward their intention, which seems again to keep the drama from too forcefully gravitating toward Lear alone, and to keep the individual man from being too much of “something.”

***

Lilli Paasikivi (Cordelia) & Matti Salminen (Lear)

From Kari Heiskanen's production of Kuningas Lear, by Aulis Sallinen

While Reimann’s score is wholly angular and erratic, even, with scenes shifting fluidly from one to the next without obvious aural clues, Sallinen’s more naturalized, melodic vocal writing is bolstered by repetitive formal structures, an oft-remarked feature of his music in general. In particular, he relies upon framing devices to draw attention to musical form, likely the result of his extensive reworking of the drama, which necessitates the imposing of a new sense of order. For example, in the first scene involving Edmund and Gloucester, which in Shakespeare begins straightaway with dialogue, Sallinen writes an arioso for Gloucester (“these late eclipses in the sun and moon portend no good”) that balances his entrance with that of Edmund, who first takes the stage earlier, with the famous “bastard” soliloquy (“Thou, Nature, art my goddess”). The composer was clearly taking the opportunity here to showcase the world-class baritone of Hynninen, who delivers perhaps the opera’s strongest vocal performance. But it also serves a larger formal purpose: the opening of the arioso, with atmospheric string chords that shift gently over a bass drone, returns at the end of the scene between father and son, thus framing the entire extended sequence. Similarly, the Fool’s song, with which the opera begins, returns intact during the scene in Regan’s castle featuring Lear, the Fool, and Poor Tom. And the women’s chorus (“Who is there? Is it man?”) from the Prologue returns near the conclusion of Act I. Such frames are the most obvious clue to Sallinen’s rootedness in a 19th-century operatic sensibility, in which formal repetitions of all sorts (bel canto’s lyric forms, Wagner's Leitmotifs) reigned as the supreme musico-dramatic signifiers.

In the role of Edmund—who stands equal to Iago as Shakespeare’s greatest villain—tenors Jorma Silvasti and Martin Homrich carry huge dramatic responsibility. Silvasti is capable enough when it comes to singing Sallinen’s more straightforward melodic lines, and he is able to produce a sense of fox-like cunning with his bodily twisting and facial grimacing, which works well enough in the opera’s first half. But when the fire heats up and the vocal and dramatic range extends, such as in the pivotal scene at the beginning of Act II when he resolves to carry out his plan to its extreme, the singer’s vocal limitations are apparent and the drama falls flat. Homrich’s enormous tenor, by contrast, is ablaze from start to finish, and fully up to the task of meeting Reimann’s vocal challenges. His opening “bastard” scene, which features an unrelenting string of superhuman high notes, is one of the opera’s highlights. That Homrich has been invited (along with Skovhus) to reprise his role in Paris in 2016 comes as no surprise. If Silvasti’s Edmund is a freak, Homrich’s is a force. The only downside of this larger-than-life performance is that Edmund’s death at the hands of his half-brother Edgar (a lighter tenor, performed by the smaller Andrew Watts, who sings countertenor when he assumes the identity of Poor Tom) comes off as highly improbable.

Erwin Leder (Fool), from Gruber-Reimann Lear

The women, too, are more strident in Reimann’s setting, with Hellen Kwon’s Regan a standout for her razor-sharp dramatic coloratura and bulldog spirit. The doe-eyed and understated Siobhan Stagg easily embodies a Cordelia who wishes to say nothing. Sallinen’s Cordelia, sung by mezzo-soprano Lilli Paasikivi, is earthier, more mature, more “something,” and therefore more poised from the start to support her father as the drama makes its way toward its conclusion.

The two composers diverge dramatically in their conceptions of the Fool. Reimann’s Fool is a non-singing character played here by Erwin Leder, a prominent Austrian actor best known for his portrayal of Chief Mechanic Johann in Wolfgang Petersen’s 1981 film, Das Boot. Leder’s nasal speech, only subtly heightened toward song, falls in line with the score’s many other distancing effects: the sometimes excessive use of speaking and laughing, and Poor Tom’s countertenor, which also verges on being cloying at times. With his protruding eyes and stealthy stage movements, Leder appears a confident and omnipotent Fool, possessing a power that lies outside of the drama, his onstage presence the ghostly vestige of something that has been obscured by the encroaching mist of nothing. Sallinen’s Fool, by contrast, takes the form of the iurodivyi, the Tsar’s Holy Fool of Russian literature (most famously portrayed in operatic form in Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov). Disheveled, dumpy, and cartoonish, tenor Aki Alamikkotervo begins the opera with his folksy song, citing his responsibility to “croon the tune.” In a wailing voice, he laments his fate (“the foolish become clever, the fool a fool forever”), thus abdicating any potential agency in the story he subsequently tells. The Fool and Lear, then, appear as equals: one is responsible for the telling (the “once upon a time, there was a . . .”), one for playing the part (“King”), neither lying more inside or outside the frame of the tale.

***

Aki Alamikkotervo (Fool), from Heiskanen-Sallinen Kuningas Lear

When Goneril and Regan gang up on their father in the play’s second act, whittling down his cohort of one hundred men (“What need you five-and-twenty . . . What need one?”), they, too, are giving voice to infinity. For where does this reduction of men in mathematical sequence end: with Lear alone, or without Lear—with less than one man, with nothing? Lear’s response (“reason not the need”) points to the gap between immanence and transcendence, reason and faith, being and not-being: there is no sensible answer to the question of why I need to be alive. This second shock to Lear’s ego (Cordelia’s “nothing” being the first) is given striking visual form in Reimann’s Lear by director Gruber, who fills the stage with a male chorus of multiple identical Lears, all in business attire and donning Skovhus-like masks. These are his knights, the men Lear’s daughters will eliminate, the one hundred making their way toward nothing. They also, of course, represent the fractured Lear. Skovhus interacts with these “himselves,” by turns fascinated and horrified, during a frenzied, cacophonous orchestral interlude featuring some outstanding virtuosic playing by the members of the Hamburg Philharmonic (the State Opera’s house orchestra). This hall of mirrors shatters as the chorus bursts suddenly into song, “old age is full of gladness and joy,” an exhilarating moment of interior becoming exterior, Lear’s self exploding into multiple other individuals.

The Regieoper affect remains strong throughout Gruber’s production, an updating—sometimes compelling, other times silly—worlds away from the dark and epic setting of the premiere production, created by famed opera director Jean-Pierre Ponnelle. Gruber invests a great deal, for instance, in projected and three-dimensional words that regularly adorn the rotating stage. The scene with multiple Lears brings to mind a specific antecedent: in his 2010 production of Don Giovanni at the Deutsche Oper Berlin, Roland Schwab employed the male chorus as identical Giovannis. Here, the visuals were even more striking (one scene involving golf clubs, with the men arranged in slanted rows, was particularly captivating), and the dramatic point was emphasized by having the men mouth the words along with the singing Giovanni (one truly was unable to tell which one of them was singing). Giovanni and Lear make great sense as a point of comparison: no more compelling pair of selves-under-siege can be imagined.

Recall that the cause of Lear’s breaking apart is Cordelia’s “nothing.” Cordelia’s act, and the question of its motivation, remains one of the play’s abiding mysteries. One of many persuasive arguments is that Cordelia (one of many in this play’s parade of the dispossessed: the blinded Gloucester, Edgar in hiding masquerading as Poor Tom, the banished Kent, the Fool) represents absolute alterity, a negative boundary of Lear’s ego, which challenges him to develop a sense of self that is directed towards the ungraspable Other. In a reading of the play inspired by Emmanuel Levinas, Kent Lehnhof notes its “relentless pursuit of the ethical” and suggests that “at play’s end, there is neither king nor kingdom—only responsibility.” Levinas, who argued that ethics (relations) and not ontology (being) should be understood as “first philosophy,” advocated just such a sense of self, one that yields its place, escapes the “there is,” allows itself to become undone. On the heath in the storm, Lear loses his reason because he attempts to evade others. His sense of empathy, too, is flawed: while he treats Poor Tom with compassion, he does so only out of an assumption that their situations are parallel: “Have his daughters brought him to this pass? / (To Edgar) Couldst thou save nothing? Wouldst thou give ‘em all?” Lear’s self is narcissistic, his empathy an act of totalizing. His feeling for the Other derives only from his view of the Other as an instantiation of himself. From this perspective, King Lear is a play concerned with the danger, perhaps even the impossibility, of empathy.

Bo Skovhus (Lear), with chorus of Lears, from Gruber-Reimann Lear

To characterize musically an operatic Lear is therefore a tricky business. Giuseppe Verdi’s famously unrealized Re Lear project, left so as much (and perhaps more) for practical than aesthetic reasons, serves as a lasting reminder of the forces required and the counter-forces needed to be overcome in successfully moving this vast and dense drama to the operatic stage. Representing Edmund’s artful evil is one thing—Verdi and Boito’s Iago alone proves opera’s ability to inhabit that space. But to capture Cordelia’s power in abjection, Lear’s inability to see and feel beyond himself, in a modern musical language that does not benefit from the predictable conventions and signals of earlier operatic repertories, calls for a musical imagination of tremendous resources. In taking on King Lear, Aribert Reimann and Aulis Sallinen venture into the most challenging of territories. In the end, Reimann’s existential drama stands as the more convincing of the two works. Sallinen’s lyrical, fairy-tale retelling makes lighter of both the ethical and the ontological registers, prioritizing instead the pure spirit of storytelling. Both operas offer interpretations of Shakespeare’s source text, as is opera’s prerogative and responsibility. While Sallinen’s more conspicuously alters the source in the spirit of creating something new, the musico-dramatic integrity of Reimann’s makes a more lasting impression, seeming—paradoxically—a truer response to the "impossibility" of a musical Lear.

Mark Mazullo is Professor of Music at Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota, where he teaches piano and a variety of courses on the history of music. He is the author of Shostakovich's Preludes and Fugues: Contexts, Style, Performance (Yale, 2010).

Banner image: Bo Skovhus (Lear), from Gruber-Reimann Lear