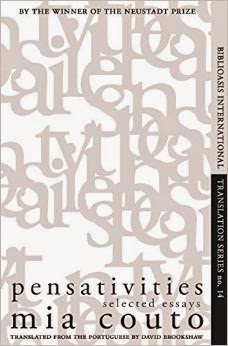

Pensativities: Selected Essays

by Mia Couto

trans. David Brookshaw

(Biblioasis, July 2015)

Reviewed by Ryu Spaeth

We are used to thinking of writing as a journey. There is the act of getting from the first sentence to the last, of laying down words that scroll across the page like a trail of footprints on the beach. There is the action of the narrative itself, which can take us, like the old Portuguese explorers, to places as far flung as the eastern shores of Brazil and the west coast of India. But most of all writing is a journey inward, through the sprawling manor of our consciousness, into the wardrobe where our various selves hang like coats, past which we discover not a solitary lamppost in a snowy wood but . . . what? A forest of mangroves and palm trees, perhaps; the ocean framed by their leafy fringe; a flamingo in shallow waters, staked to its shadow; the cupped shoreline that is the bay of the soul.

This is not merely a voyage of discovery, but also one of creation. “I am the sum of my books,” V.S. Naipaul once said, describing a body of work that had taken him from his birthplace in Trinidad, a one-time colony off the coast of Venezuela, to England, the Indian subcontinent, the Middle East, South America, Africa, and back to the Caribbean. If we traced his travels across the world, we would find a web as tangled as history. It represents a heroic effort to swallow whole the entire colonial legacy, as if this would dissolve, like an antacid, the bitter confusion that it engendered in the pit of his being. “The aim has always been to fill out my world picture,” he said in the same lecture, “and the purpose comes from my childhood: to make me more at ease with myself.”

To make one more at ease with oneself: it sounds like a humble endeavor. But it is likely that the salvation of the postcolonial world lies precisely in a similar inner journey and triumph — over ignorance, over the mendacious claims of history, over the poisonous doubts about identity that can redden the mind like malaria. If we are to reach that spot on the ocean — a place that in this essay we will call the Mozambique of our dreams, though with slight variations it could just as well be Rio or Goa — then we must first figure out who we are. This will not happen of its own course, resulting in the emergence of a confident new postcolonial citizen from a primordial soup of conflict and poverty; he must be forged the way Adam was, in the fires of the imagination.

This is the grand theme that arches over Pensativities, a collection of essays and speeches by the Mozambican author Mia Couto that have been translated from the Portuguese by David Brookshaw. For Couto, the postcolonial project is not primarily political or economic; it is humanistic in nature, and literary in its means. Its aim is to reconcile history and myth, past and present, subjugator and subject. It brings together black and white, male and female, Africa and the West, young and old, the city and the bush. It seeks to mediate between the outside world and the life of the interior, and to translate between the multitudes within a person. It is the way of the poet, instilling the poet’s sensibility into issues of development and good governance.

One of the many advantages of this approach is that Couto’s Mozambique is strange and new, stripped of the glaucous fog of World Bank statistics and media bullet points that make so many sub-Saharan countries virtually indistinguishable. We could note that Mozambique is one of the poorest countries in the world, that a very large number of Mozambicans live on less than a dollar a day, and that a full 12 percent of adults, as of 2003, carry the HIV virus. We could sketch a timeline: independence from Portugal in 1975, followed almost immediately by 15 years of civil war, followed by peace accords in 1992 that gave way to a tenuous stability. And we could offer a diagnosis of its economic ills: scarred by socialism, hobbled by mismanagement, dominated by foreign aid, hampered by natural disasters, the economy’s best hope lies in the country’s wealth of natural resources and a budding ecotourism industry.

But all this, however useful, is a foreign language — an imposed tongue that Couto scornfully refers to as “developmentalese” — that not only makes Mozambique obscure to foreigners, but to Mozambicans themselves. “For us, too, there is a Mozambique that remains invisible,” Couto writes in the book’s first entry, “The Frontier of Culture,” a speech to Mozambican economists. The Mozambique that he makes visible is a hybrid entity unique among nations, like those rare creatures, half-mammal, half-bird, that are produced by the quirks of geologic history. Located on the southeastern coast of Africa, facing the island of Madagascar and the Indian Ocean, it has been crossed from both East and West, by Europeans and Asians, who left their influences behind like so many scattered seeds. Linguistically it is part of the Lusophone community, which is literally all over the map: Angola on the other side of the African continent; Portugal of course; East Timor and Macao in Asia (as well as India’s Goa, though less and less so); and most influentially, at least for Mozambique’s Lusophone writers, Brazil, whose own poets showed how the colonizer’s language could be changed from within and made one’s own. And inland, toward South Africa and Zimbabwe and Zambia, are Mozambique’s rural communities, some of which share more in common with their tribal counterparts, both linguistically and culturally, on the other side of the border. Couto sees in these people a source of Mozambique’s patrimony, but for the young coastal elites he once taught at university, “[t]heir country was somewhere else,” he writes. “Worse still: they didn’t like this other nation.”

At first glance, Couto may seem like an odd candidate to connect young black Mozambicans to their ancestral roots: he is white, the son of Portuguese emigrants, most of whom fled during the aftermath of independence and the civil war. But in other ways he is the ideal mediator between Mozambique’s disparate identities. He is of the generation that came of the age during the independence movement, “between a world that was nascent and another that was dying,” as he writes in the essay “Waters of My Beginning.” He is not only a poet and a novelist: he is a biologist by trade, an occupation of political importance in a country famous for its unique ecosystems, and for a long time he was a journalist and activist, which gave him an intimate, on-the-ground knowledge of his country. He is a public intellectual in the truest sense, fluent in almost every area of concern to Mozambique, and he is an ardent patriot, the kind who can declare, in an essay on his days as a pro-independence activist: “The world was my church, men my religion.”

But most importantly, he was born into a borderland between peoples and places, “between the sea and the continent, between Europe and Africa.” He is neither here nor there, a state of exile that produces a divided self. His very person is a reflection of the country that he loves, and so what saved him is, like an experimental vaccine, of vital importance to everyone. “My two sides demanded an intermediary, a translator,” he writes. “Poetry came to my rescue, to create a bridge between two worlds.”

A pragmatist (or perhaps an economist at the IMF) may roll his eyes at that. And it would certainly be a foolish kind of vanity to mistake the writer for the world. But we are all familiar with the perils of identity politics, and how they are used to divide people and perpetuate the interests of the powerful. Those who say they speak for a “real Africa” are no less demagogic than the Fox News pundits who claim to be the guardians of the “real America” or the Hindu nationalists who refer to the Indian panoply as “Hindustan.” Couto’s argument is that Africans in general, and Mozambicans in particular, need a new kind of political language, one inspired by literature, that lets them see the other in themselves. Needless to say, this concept is especially valuable for a continent that has been riven by the most appalling ethnic violence, wherein the compatriot becomes the enemy and the neighbor a demon. From “The Frontier of Culture”:

Africa cannot be reduced to a facile, easy-to-understand entity. Our continent is made up of profound diversities and complex hybridities. Long and irreversible processes of cultural mingling have molded a patchwork of differences that constitute one of the most valuable patrimonies of our continent. When we mention these mixtures, we do so with some unease, as if a hybrid product were in some way less pure. But there’s no such thing as purity when we talk of the human species. There is no contemporary economy that isn’t built on trade. In the same way, there’s no human culture that isn’t based on some far-reaching transactions of the soul.

Couto suggests that this fear of the other — sown by the colonist, cultivated by the homegrown strongman — has spread like a weed to into every area of African life. The perceived list of what is not authentically African is boundless: wealth, modernity, literature, science, democracy. And so, paradoxically, the fear of the other curdles into a crippling hatred of the self. If the Mozambican nouveau riche seem uncomfortable in their own skin, it’s because “[t]hey aspire to be others, far removed from their origins, their condition.” If Africa has yet to become modern in the fullest sense, it’s because “[t]he thought that Africa might produce art, science, and ideas is alien even to many Africans.” If hard-won freedoms and democratic institutions seem to exist in a state of perpetual fragility, it is because they have yet to be “transformed into culture within each one of us.”

The subtitle of this book is “Essays & Provocations,” and perhaps the most provocative aspect of Couto’s political philosophy is his treatment of colonialism and slavery. For there is no other more menacing, more monstrous, than the colonist and the slave trader, both of whom continue to be blamed for Africa’s post-independence ills. Even if this mentality is justified, Couto calls on Africans to abandon it, simply because they have no other choice. “‘History is in debt to us,’ this is what we think,” he writes in “The Planet of Frayed Socks,” a speech to a development conference. “But History is in debt to everyone and doesn’t pay anyone back.” In a line that will echo debates about the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow in America, he says, “The solution for the underprivileged isn’t to ask for favors. It is to fight harder than others, above all to fight for a world in which favors are no longer needed.” More radically, he claims that Africans recognize themselves in their oppressors, for many Africans, in fact, participated in the selling of slaves and colluded with the colonizers. The false notions that all Africans were entirely innocent, and that “pre-colonial Africa was a world beyond time, without conflict or disputes,” he writes, “ends up giving sustenance to an attitude of eternal victimhood.”

This is strong stuff, and it will doubtless turn off some. But it would be wrong to conclude that Couto is the type to blame the victim; rather, it represents a part of his larger project to cultivate “fully integrated persons” who can contain within themselves all the contradictions of history and being alive. As he writes in “The Planet of Frayed Socks”:

The history of each one of us is that of an individual on a journey towards personhood. What makes us into people isn’t our identity card; what makes us into people is that which doesn’t fit on identity cards, is the way we think, the way we dream, the way we are others. So we are talking here about citizenship, about the possibility of being unique and singular, about our ability to be happy.

This journey, a grand synthesis that is almost orchestral in its complexity, is much to ask of any person. It is even a challenge for Couto himself, whose fiction seemingly attempts to hold all of Mozambique together with the superglue of his creative powers. His latest novel to be translated into English, also by David Brookshaw, is Confession of the Lioness. It is inspired by an actual event in Couto’s life: he was part of a group of environmental field officers sent to Cabo Delgado, in northern Mozambique, in 2008 to monitor an oil company’s seismic explorations. The expedition coincided with a spate of lion attacks on villages in the area, prompting the company to hire hunters to kill the lions. As the hunters struggled to dispatch these elusive predators, the lions began to take on an otherworldly hue and were seen by the more superstitious villagers “as inhabitants of the invisible world, where rifles and bullets were no use at all.”

The novel features a hunter, a mulatto named Archangel Bullseye, who is hired to track down lions that have been killing women in the remote village of Kulumani. The villagers are the type of marginalized people who exist outside official histories, and their toehold at the barren edge of the world is captured in a quick sketch: “I looked at the houses that stretched out along the valley. Discolored, gloomy houses, as if they regretted emerging from the ground.” Their alienation also means that they operate under a different concept of time, shorn of dates and context, that stretches back one, two, maybe three generations before trailing off into the mists of myth. As Archangel’s life in the city recedes, and he delves further into the strange life of the bush, we progress toward this mythic reality, toward the invisible world, which is a fitting progression for a novel.

The dichotomies that lay at the heart of the book would appear to align perfectly with Couto’s interest in synthesis. These poles include urban and rural, black and white, and most significantly, men and women, whose bodies, like Africa itself, have been the site of so much horrendous abuse. The problem, unfortunately, is that the novel is so badly overwritten that much of what Couto is trying to say gets lost; it contains none of the bracing directness and lyrical beauty that are found everywhere in Pensativities. To provide just one example from Confession of the Lioness of prose that is both overwrought and borderline nonsensical: “It was like a stone thrown into a puddle without any water. Adjiru’s astonished look was like a wound ready to be opened.”

“Worse than not writing a book,” Couto observers in a speech about Brazilian writers, “is overwriting it.” While I wouldn’t go that far, it’s as good an excuse as any to return to Pensativities, which brims with truly inspiring writing that hums with the moral force of Camus’s best political essays. As Camus, also born in a colonial African country, once wrote of the violent struggle for independence that tore apart his beloved Algeria, “Although it is historically true that values such as the nation and humanity cannot survive unless one fights for them, fighting alone cannot justify them (nor can force). The fight must itself be justified, and explained, in terms of values.”

The values that Couto imparts are in some ways subtle, because they come from the depths of his inner travels. “There are as many Africas as there are writers,” he says, “and all of them are reinventing continents that lie inside their very selves.” In another essay, he says, “The world no longer lives outside a map, and it doesn’t live outside our own inner cartography.” But his fundamental values — inclusiveness, honesty, empathy, courage — should not be dismissed merely because they are born from self-reflection. When reading Couto, it sometimes seems that it is not only the fate of Mozambique or even Africa that is at stake, but that of the whole world. The problems he discusses are not unique to Mozambique, even if the shape of his hopes takes his country’s form. If we, in America and elsewhere, could be as he asks us to be, then I believe we would solve this infernal problem of identity.

Ryu Spaeth is a deputy editor at TheWeek.com, where he has written about books, movies, politics, and more.