Les Pigeons d'argile

by Philippe Hurel

with a libretto by Tanguy Viel

Gaëlle Arquez (Charlie), Aimery Lefèvre (Toni), Vincent Le Texier (Bernard Baer), Vannina Santoni (Patricia Baer), Sylvie Brunet-Grupposo (Police chief), Gilles Ragon (Pietro), Dongjin Ahn (Bank employee)

Orchestre National du Capitole de Toulouse, Chœur du Capitole

Tito Ceccherini (conductor)

Mariame Clément (director)

Maria Hansen (set & costumes)

Philippe Berthomé (lighting)

Momme Hinrichs, Torge Møller (video)

(Éole Records DVD, July 2015)

A few years ago when an old school friend came to visit me in London I brought him to the Tate Modern to see the permanent Surrealism exhibition. We looked at famous canvases like Ernst’s The Entire City, de Chirico’s The Uncertainty of the Poet, and Bacon’s Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion. As we strolled afterwards up the south bank of the Thames, my friend turned to me and, in a measured voice, accused me of having deliberately exposed him to disturbing art—to dark, grotesque, psychosexual images, despite knowing he had a sensitive mind. As I reeled, he added that he had no desire ever to look at pictures like that again.

♦

For some—and I’m among them—art is a sort of willed violation—a violation via the senses, a disorientation to which we submit, willing ourselves to be manipulated and strung out. This is what we actively seek in art—a violence that blasts the dirt from our lenses, makes everything keener and more piercing—the temporary destruction of our mundane surroundings. We submit to this violation as patients (the meaning of passion). We submit to a sensory violence from which we derive pleasure—even power.

♦

No small part of the pleasure of French composer Philippe Hurel’s music lies in the violence of its acoustic images. The opening of Pour l'image (1987) for ensemble is indicative: a cloud of woodwind sounds swarm deliriously, like flies over a pond, gradually growing more cohesive until we find not the disarray of the initial multitude but the flash of a unified group—no longer a teeming of sounds but one massed sound—polyphony, in other words, flexed into homophony. Hurel creates these acoustic images through a process called “instrumental synthesis,” whereby the small-scale frequency structure of sound waves serves as a model (via spectrographic analysis) for the pitch content of large-scale chords. The auditory impression—as in the swelling chords issuing from the orchestra throughout Les Pigeons d’argile—is of a visceral attack of sound. It’s a quality described in French by the infinitive surgir—“rushing up” or “manifestation”—and it’s a happy coincidence that manifestation can denote civil disobedience in French.

♦

Les Pigeons d’argile (“Clay Pigeons”) is Hurel’s first opera. After a brief prologue, the first act opens with the terrorist Charlie (mezzo Gaëlle Arquez) sat up in bed in front of a bed board onto which has been prominently daubed the image of Arthur Rimbaud; the sympathy of experimental art and insurrectionary violence established right away. The simplest Surrealist act, we remember, is shooting at random into a crowd.

♦

Les Pigeons d’argile is based on the Patty Hearst affair. In 1974 the nineteen year-old Patricia Hearst, granddaughter and heiress of the media tycoon William Randolph Hearst (model for Citizen Kane), was kidnapped from her home in Berkeley by a terrorist group called the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA). This was the era in the USA of the Weathermen and other left-wing “terror” groups, and the media fed frenziedly on the story as negotiations began for Hearst’s release. What happened next took everyone aback: the SLA held up a bank, and when the CCTV footage was retrieved, one of the bank robbers turned out to be Patty Hearst. In an apparent case of Stockholm syndrome she’d opted to join her kidnappers in their anarchistic revolutionary aims. A photo was subsequently released—since become famous—of “Tania” (the nom de guerre taken by Patty), dressed in guerrilla combat regalia and a beret, posing with a Kalashnikov in front of the red SLA flag.

♦

Gilles Ragon & Vincent Le Texier

Tanguy Viel’s libretto for Les Pigeons d’argile transposes the tale to France in the past five or six years, with Hearst restyled as the French Patricia Baer (soprano Vannina Santoni). A love story takes central place: the relationship between terrorists Charlie and Toni (baritone Aimery Lefèvre) becomes threatened when Toni falls for the kidnapped Patty. Minor characters feature: Patty’s father Bernard Baer (bass-baritone Vincent Le Texier), a business magnate; Toni’s father Pietro (tenor Gilles Ragon), an aged socialist and caretaker of the Baer estate; and a police chief (mezzo Sylvie Brunet-Grupposo). That the Patty Hearst episode is transposed to France—site of the Revolutionary Republic, the Terror, the Paris Commune, the lost revolution of May ’68, and (now) the recent Islamic State terror attacks—is deliberately provocative.

♦

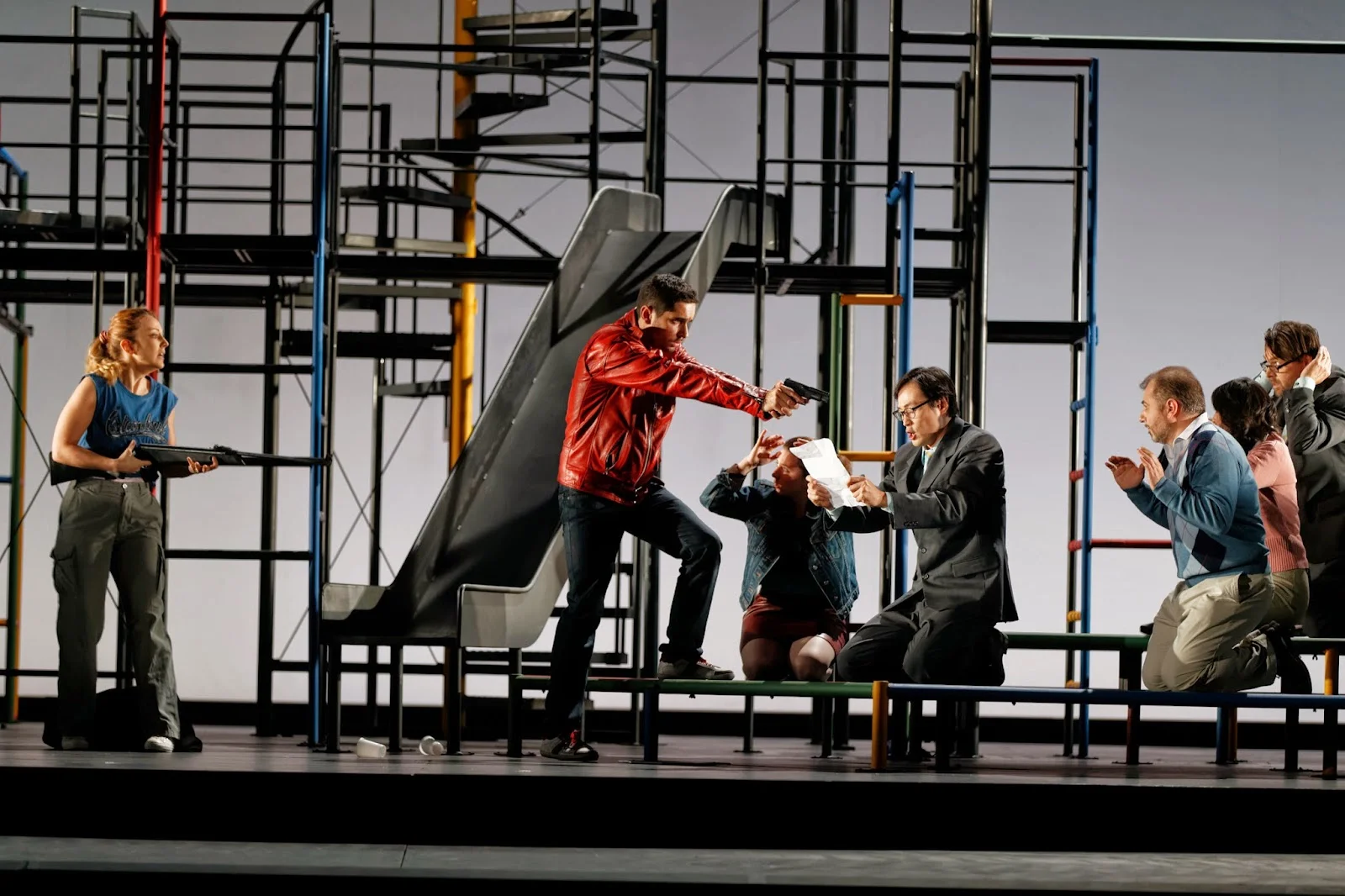

Toni and Charlie are typical left-wing youths. They dress in the standard hoodies and leather jackets of their milieu; they are unhappy with the world bequeathed by their elders. When Toni and Charlie decide to channel their disaffection into armed terrorism, they shoot a homemade video outlining their new constitution. “Article Three,” Toni says. “We operate in the invisible.” Charlie brandishes a handgun: “Article Four: The world will collapse, whether it be by us or with us.” Behind the stage the video streams, like an IS propaganda video. “We will make an incision in history,” Toni tells the camera. “We will tear apart the social body, lacerate it. Our struggle will be against baseless Humanisms—young girls with beautiful voices—Beauty has no control over us.” Again, an echo of Rimbaud: “One night I sat Beauty on my knees.—And I found her bitter.—And I insulted her. I took up armed revolt against justice…” In a violation of order and beauty alike, Patty is kidnapped by the gun wielding terrorists as she sings “Ach, ich fühl’s” from Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte.

♦

Hurel had to overcome some reservations about writing an opera, he says, a form he considered anathema to his aesthetic. For me, though, opera at its best captures—or rather, presents—a certain state of emergency: the unforeseen explosion of a world (explosion either as growth or destruction), whether that effects the destruction of the private world of lovers (Pélleas et Mélisande) or the destruction of a wider public world (Götterdämmerung). Despite facile connotations as being the art form of elitism and wealth, opera has a power sans pareil of putting us in touch with elemental, pseudo-apocalyptic violence—a sort of cultivated rawness, the aesthetic violence of voices pushed to their limit, extremism of actors swirling in an orchestral cauldron. The emergence in opera of this “third world” onstage (the expression is Gerald Barry’s, whose operas veritably bathe in violence) is as the quickening emergence that confronts us in a state of emergency. In this regard Hurel as composer and Patty Hearst as subject are well matched to opera’s potential.

♦

Talking about literature, but making a point that easily transposes to music, Maurice Blanchot writes: “Revolutionary action explodes with the same force and the same facility as the writer who has only to set down a few words side by side.” Describing the Terror that followed the French Revolution, Blanchot continues: “the Terror [Robespierre et al.] personify does not come from the death they inflict on others but the death they inflict on themselves. [...] The terrorists are those who desire absolute freedom and are fully conscious that this constitutes a desire for their own death, they are conscious of the freedom they affirm.... The writer sees himself in the Revolution. It attracts him because it is the time during which literature becomes history.” The revolutionary moment is a time of suspense. Blanchot concludes: “Death as an event no longer has any importance.”

♦

Few novels open more arrestingly than Gravity’s Rainbow. The reader is shunted in medias res into a cataclysm eviscerating London: “Screaming holds across the sky […]. The walls break down, the roofs get fewer and so do the chances for light […] great invisible crashing.” A thrilling spectacle, a circus of destruction, Pynchon’s exploding London echoes at a distance the city of Rimbaud’s Illuminations—a fragmentary space, full of “spectres rolling through the dense eternity of coal smoke—our woodland shade, our summer night sky”—a space full of “angels of fire and ice.” In each case, the reader luxuriates in the destructive scene.

♦

Aimery Lefèvre & Gaëlle Arquez

Les Pigeons d’argile’s subject matter, an anarchic one, is placed on a leash through the use of a traditional operatic template. Three-act structure is adhered to; the tenets of tragic romance are adhered to. Patty Baer is a winsome soprano; Toni, a Heathcliff-passionate baritone; Charlie, the jilted girlfriend, an insecure mezzo; the wealthy Bernard Baer, a lordly bass. In the scene that introduces Bernard Baer, a chorus takes to the stage, journalists and admirers fawning over the business mogul’s achievements (Hurel and Viel here parody Citizen Kane: “Il y a un homme, / Un certain homme. / Quel est son nom ? / Quel est son age ?”). Hurel’s vocal writing eschews awkward jumps and abrupt spikes. The style is declamatory, the phrasing according to the natural rhythms of speech. The singers’ lines are punctuated throughout by brief flashes of color from the orchestra. The operatic action is continuous rather than episodic—though Hurel does open each of the three acts with a lyrical, aria section. This retrained approach is in one sense a relief from contemporary opera that goes out of its way to appear “edgy” and falls flat on its face. Opera is visceral enough without having to be portentously “avant-garde” in style. In another sense, though, the restraint means Les Pigeons d’argile stands safely back from rather than leaping dangerously into the moral abyss—that thrilling excision of morals—occasionally glimpsed. By comparison with Patty Hearst, Patty Baer is for me altogether too bland a creation—more fairytale princess than Angel of Death.

♦

A terrible beauty is born, wrote Yeats about the bloody mess of the 1916 rebellion in Dublin, which gave eventual birth to the political entity of the Irish Free State. Is Yeats’s remark completely dissociable from a recent political dissident hailing A beautiful terror? That was also the question Karlheinz Stockhausen asked in the days immediately following 9/11, when he notoriously called the attacks “the greatest work of art imaginable for the whole cosmos.” It hardly seems coincidental that he was just then completing a massive cycle of seven operas.

♦

What is the fascination of Patty Hearst? In part it’s down to the seductiveness of that color photo of her holding a Kalashnikov—an aesthetically brilliant image—an icon—this beautiful young woman in a low-cut top wielding a lethal weapon, offering the serious threat of killing and the playful eroticizing of violence (shades of Bonnie and Clyde). In line with this, the fascination inheres further in the fact that this exciting, ridiculous Patty Hearst story “actually happened in real life.” This icon bears witness to an unforeseeable emergence—an immaculate conception—embodying an obscure, hoped-for transcendence. Alongside the Patty Hearst icon’s fusion of eroticism and violence, there is the reality that it beggars belief—as if a character from fiction somehow came true—a dangerous and seductive prospect.

♦

After skipping Paris during the last weeks of the German occupation, Louis-Ferdinand Céline ended up with other personae non-grata, collaborators, and the Vichy government in Sigmaringen Castle (in Bavaria), acting as Pétain’s doctor. In the novel From Castle to Castle, Céline describes the strange, suspended atmosphere there, a “mode of existence” that was “neither absolutely fictitious nor absolutely real […] a fictitious status, halfway between quarantine and operetta…” Opera seems to name well this state of suspension, as it does for Rimbaud in A Season in Hell—raking the coals of his infernal life with Verlaine—describing when life “became a fabulous opera.”

♦

Sylvie Brunet-Grupposo

Despite perhaps playing it slightly safe in characterization, Hurel and Viel’s Les Pigeons d’argile is one of the better new operas I’ve seen in recent years—albeit seen in this case on a DVD rather than in an opera house. (The DVD, by the way, has only French subtitles.) Hurel’s score is by turns searing and lush; Mariame Clément’s production smoothly executed and topical; Viel’s libretto well-paced and suggestive (if a little formulaic); the cast uniformly persuasive and in good voice. In terms of Hurel’s oeuvre it builds promisingly on his general style, as well as specifically on the recent vocal works Espèces d’espaces (after Perec) for actor, soprano, ensemble, and electronics, and Cantus for soprano and ensemble, where the vocal style at times recalls jazz singing. Les Pigeons d’argile bodes well for operas yet to come from Hurel.

♦

I look again, in closing, at that famous picture of Patty Hearst, posing with a Kalashnikov—she’s of my general age-group, at the time of the image—she’s donned this costume, she’s adopted this military pose, she’s been photographed—and it’s all as if in an opera—all an extravagant work—it’s even of the essence of opera—apocalyptic spectacle—lacking only the music—a personification of worlds exploding and touching each other’s skin—the violence of becoming—compulsive, seductive violence of art.

Liam Cagney is a musicologist and author, and is currently a visiting lecturer at University College Dublin. His writing has appeared in Gramophone, Opera Magazine, Sinfini, Gorse, and elsewhere.

Image credit: Patrice Nin