Femenine

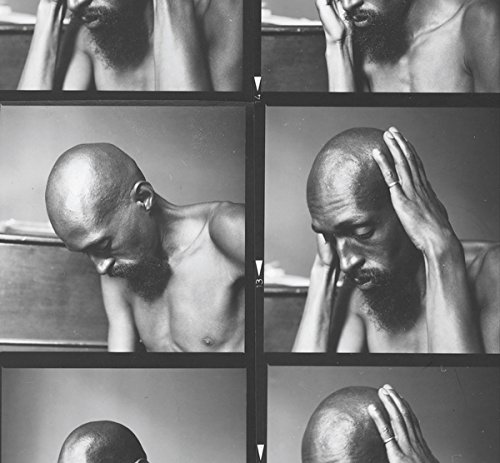

by Julius Eastman

SEM Ensemble

(Frozen Reeds, Sep. 2016)

Reviewed by Ian Maleney

Though it may be a vague and cloudy thought, I often return to the metaphor of “surface” as a way of describing pieces of music. It seems particularly useful when thinking about the music made in or around New York (and, to a lesser extent San Francisco) during the 1960s and 1970s. Morton Feldman wrote in 1976 that it was his primary concern, throughout his work and particularly with For Frank O’Hara (1973), “to sustain a ‘flat surface.’” Feldman had explored the idea more seriously in 1969, detailing a conversation with the artist and critic Brian O’Doherty, wherein O’Doherty made a valiant attempt to define what is meant by a music’s “surface,” and how it is distinct from that of a painting. “The composer’s surface is an illusion into which he puts something real — sound,” said O’Doherty. “The painter’s surface is something real from which he creates an illusion.”

The musical surface is certainly an illusion, but it is never less than apparent when a piece of music possesses one. It has something to do with coherence, with various parts forming a whole in a way which is impossible to untangle. This idea of a musical surface might have been born with Feldman or indeed earlier, but it was in the work of the so-called minimalist composers that it became something essential. For the sake of pursuing this thought, we might indulge in a little reductionism and further break up minimalism into two historical schools: on one side, the glistening patterns of Steve Reich and Philip Glass; on the other, the bottomless drone of Terry Riley and La Monte Young. In the former, surface is something the listener is carried along on top of, something which pitter-patters along with a forward motion of its own; in the latter, it is something to be submerged beneath, something in which the listener wallows or even drowns. Feldman, always thinking vertically, gives us the image of a landscape laid out below a bird. Whatever the conception, it’s all about perspective.

Julius Eastman’s perspective on minimalism is no easier to pin down than this metaphor of surface. In one of the essays included in the recently published Gay Guerrilla: Julius Eastman and His Music, Matthew Mendez explains how Eastman’s Wood In Time—which consisted of a homemade mechanized maraca-like instrument beating out a single, unchanging rhythm for around ten minutes—could be understood as both a parody of Glass & Reich’s metronomic rhythms and a precursor to his own most identifiably minimalist piece, Stay On It. Mendez describes Eastman’s take on the new genre as being “arch, and not a little tongue in cheek,” and contrasts this with his appreciation for the music of Frederic Rzewski. In Rzewski’s music, largely unlike the instrumental works that Glass and Reich are best known for, “the ‘outside world’ of politics and the vernacular was readily embraced.” Perhaps this explains the degraded, pock-marked, porous surface of Stay On It. The piece might consist mostly of a single, repeated “riff” and an interlocking set of largely rhythmic ideas, but it is ultimately about the interruptions; the ‘outside world’ pokes its dissonant head through the illusory surface and banishes the idea that what we’re hearing might be nothing more than an inventive and pleasant exercise in modular composition. There is a surface, but there’s something beneath it too.

The automated rhythms of Wood In Time also foreshadow the mechanical sleigh bells which are a steady but subtle presence in another Eastman piece, Femenine [sic]. In the recording of Femenine—made by Steve Cellum at a 1974 performance by the SEM Ensemble with Eastman on piano, and now released by the Frozen Reeds label—the bells are the first things you hear which speak of music. They start off on their motorized jingling, and a space is cleared for music to happen, to unfold. It’s an ancient technique; from Amazonian tribes to Christian mass, many rituals begin with the shaking and ringing of bells. Bells are truly complex sonic objects, and when they ring in communion with each other the layering of tones is both chaotic and comforting. As mnemonic devices, they speak of alertness, of coming-to-attention—bells are some of the oldest alarms. As sonic devices, any attempt to follow them inevitably leads the ear down tangled paths, and draws the mind away from self-absorption. They clear the air: “Listen, something is coming.”

The mechanized bells immediately provide Femenine with a more rigid framework than Stay On It, which lacks any such persistent presence. The first instrument to enter into this framework is the vibraphone, which plays a repeated melody; first fast repeated notes, then six slow, alternating notes. This melody slides around the constancy of the bells, fast and then slow, in and then out, pushing and pulling back. It feels like watching a rower gather momentum on a flat river—the oars, the water, the lungs all searching for some kind of alignment. Slowly, slowly it takes shape and the whole thing begins to move. When the piano chords state themselves, gentle and soft at the bottom of it all, they sound like how a body of warm water feels. For now, for these first few beautiful minutes, there is no tension at all. There is just a gathering of force, a calm and expert pulling together of muscles, chords and breath which, swelling, envelops all before it.

It goes on like that, the melodies gradually knotting themselves together before slipping apart again, repeating the process in dozens of different ways. With each listen, different combinations appear particularly noticeable, patterns suddenly perceived within the overall organism. Around the eighteen-minute mark, the violin changes its tune and something almost folksy emerges. It’s not out of place, but it does seem to be pulling in a slightly different direction to what’s happening around it. There’s a hint of Appalachia about the simple draw on the strings, but it’s gone almost as soon as it appears. It’s probably just an illusion. Soon the patchwork thins out, the acceleration slows, the tide goes back out. Still the bells ring, and the vibraphone trills, but the piano begins to hammer chords in the bass before dying away completely, and the strings fade into the air. Just as easily as it came together, so it all comes apart, as natural an intake of breath before a long push toward something different.

When eventually the space fills back up again, it is almost but not quite the same scene. It is hard to say whether we’ve heard before what we’re hearing now, or whether this is some mutation or evolution of those original melodies and patterns. This is the “organic” part of Eastman’s later notion of “organic music”—it seems more like natural growth than linear development towards a desired end. The music evolves outwards, spiraling away from the central melodic themes until they exist only as a memory, or as a ghostly presence, invisibly rooting the piece in place. Meanwhile, a new set of ideas has been threaded into the pattern, each variation in melody or rhythm setting off new progressions elsewhere. This constant swell of micro-evolution is a product of the musicians listening intently to each other in real time, a devolution of responsibility which keeps the musicians in lockstep while refusing the blissed-out trance-states typically associated with such rigorous and unrelenting repetition. Mendez quotes Eastman’s frequent later collaborator, Arthur Russell, describing the approach as “hearing what you do while you do it.” This is participatory, inherently social music and, as Mendez points out, is much more akin to open-ended jazz than a recital piece.

Like any society, Femenine changes over time. It evolves even as it settles into a recognizable groove. More than anything, it deepens. The perspectives of both listener and musician on the material deepen with time, and it is worth remembering that Femenine, like many of Eastman’s later pieces, was often performed with a digital clock on stage marking time as it passed. “A music that has a surface constructs with time,” O’Doherty told Feldman, a little later in their conversation. “A music that doesn’t have a surface submits to time and becomes a rhythmic progression.” What is Femenine’s relationship to time? Can we say it constructs with or submits to time? Feldman said that to construct with time, to create music with a surface, was to let time be—not to parcel it out as you wish, but just to let it be. Eastman putting a clock on stage seems to say something else: we might very well let time be, but time will never do the same for us. When our time is up, it’s up.

During the final twenty minutes of Femenine, it becomes impossible to distinguish foreground from background, surface from depth. There are so many intersecting ideas present at all times that no one statement emerges as definitive. Though the bass-heavy chords of the piano boom loudly below the upper-register strings and woodwinds, they do not overwhelm them. Their loudness doesn’t make them stronger, or more powerful. If the opening vibraphone melody—that push-and-pull figure—was a means of drawing the listener in at the beginning, the final stretch is proof of utter submersion. The music is all around, in every direction at once—it feels like floating. There are moments, particularly in the final ten minutes, which could well be described as “New Age,” and those winsome flute melodies are as relaxing as could be. The piano’s delicate scales wash up and down like the ocean against the coast.

It is worth returning to the idea of intersection, or better yet, interpenetration. The Scottish anthropologist Tim Ingold speaks a lot about interpenetration, or what he calls “knotting,” and uses the idea as a way of thinking about knowledge and how societies function. Walking, we penetrate the earth very slightly, leave marks, and walk our way into knowing—paths, routes, connections. As friends, lovers, co-workers, we interpenetrate each other’s lives to the point where we are distinct but essentially inseparable—I can’t imagine my life without you. Interpenetration is a fundamental part of Femenine, on just about every level. Each part played by each musician is open to intersection with the others; rather than being defined parts of a whole, they remain autonomous even as they combine and work together in the moment. They correspond. On the level of style, jazz and pop interpenetrate the formal rigor and the classical sense of structure and presentation. Even within Eastman’s work, Femenine would seem to be a counterpart to Masculine, a now lost piece which, Mendez points out, was sometimes performed at the same time as Femenine, in another part of the same venue. The two pieces happening simultaneously—distinct and yet, for the listener, experienced as inseparable—provides a tantalizing refusal of binary thinking. Each piece opens onto the other, and there is no beginning or end to either as they happen.

In all these senses, Femenine is, as Hua Hsu recently wrote, “politics by other means.” The surface of the music is penetrated by the political and social identities which composed it, and by those who have heard it. It does not shy away from the associations a word like “feminine” carries with it, but instead of simply illustrating those associations, Eastman questions and complicates them. The music resists codification at every level, resists saying that something is this because it is not that. To take the title of a book about Brian O’Doherty (a man not afraid of blurring identities), Femenine is between categories. It is precisely this which makes it such a rich listening experience: it seems always to be opening up onto something else, always letting in something new. In Femenine, Eastman finds value and power not in wholeness—not in limits and definitions—but in openness, in vulnerability, in being porous.

Ian Maleney is a writer living in Dublin, Ireland. He writes about music, literature, and politics for a broad range of publications, in Ireland and elsewhere. He is editor-in-chief at Fallow Media.