Émilie Suite, Quatre instants, Terra Memoria

by Kaija Saariaho

Karen Vourc'h (soprano)

Orchestre Philharmonique de Strasbourg

Marko Letonja (conductor)

(Ondine, Jan. 2015)

Reviewed by Angus McPherson

Kaija Saariaho’s compositions have always drawn on a wide-ranging variety of literary sources, from Amin Maalouf’s powerful librettos to Ezra Pound’s experimental Cantos. Two albums released in 2015 by Ondine explore the Finnish composer’s relationship with literature through works for orchestra as well as more intimate chamber music. The first of these presents works for orchestra and soprano performed by the Orchestre Philharmonique de Strasbourg with Marko Letonja conducting and Karen Vourc’h as soloist, while Let the Wind Speak explores Saariaho’s flute chamber music from 1982 to 2012. Although electronic music and blends of acoustic and electronic sound were an important part of Saariaho’s palette in the earlier stages of her career, both these discs feature only acoustic works. The virtuosic manipulation of color in these works, however, demonstrates that the haunting sense of transcendence for which Saariaho’s music is known is by no means limited to her work with electronics.

The first work on the orchestral disc, Quatre instants, began life as a piece for voice and piano, and was subsequently arranged by Saariaho in 2002 for soprano and orchestra. The sparseness of the writing reflects the original conception, though Saariaho harnesses the colors and effects of the orchestra to create a far greater sense of depth and sophistication than was possible with the piano, expertly painting the unsettling inner monologue of the text by Lebanese-born French author Maalouf. Saariaho writes in her program note: “Trying to extract the colors I had in my mind from the piano, and at the same time adapting its vast and expressive scale to the diminutive vocal lines, reminded me of the work of a jeweler, who, with the help of a loop, creates rich, microscopic details.” The four Instants are each associated with a different facet of love. In the first, Attente (“Longing”), the orchestra creeps and churns beneath Vourc’h’s gleaming soprano, her delivery of Malouf’s “Je suis la barque qui dérive” (“I am the boat adrift”) plaintive and moving. Douleur (“Torment”) is more violent, the text dwelling on self-hatred and regret. A vivid evocation of scent and emotion, Parfum de l’instant (“Perfume of the instant”) is quiet, with sliding strings providing an understatedly nightmarish quality. The text of Résonances (“Echoes”) brings together material from the previous three movements, reliving the longing and torment through the lens of memory. While the text of the first three movements existed prior to Saariaho’s composition, Malouf created Résonances expressly at her request, thereby tying the motifs of the work into an elegant cyclical structure.

Saariaho’s 2009 opera Émilie, a musical monodrama, is a portrait of scientist, mathematician, and physician Émilie de Châtelet (1706–1749), one of the earliest female scientists. Châtelet predicted the existence of infrared radiation, and her translation of Isaac Newton’s Principia mathematica remains the standard French version of the text even today. Saariaho’s opera, originally in nine sections, is here condensed into a five-movement suite—three movements with vocal soloist and two instrumental “Interludes” (the opera’s electronics didn’t make it into the concert suite). The action of Émilie takes place during a single night, when Châtelet was in the final stages of the pregnancy that would lead to her death six days later.

Châtelet was known to have played keyboard, and improvisatory harpsichord gestures in the opening Pressentiments (“Forebodings”) serve to evoke the eighteenth-century backdrop, as well as to conjure an intense sense of loneliness—Châtelet isolated in the empty Château de Lunéville. The text takes the form of a letter written by Châteletto her lover and the father of her child, the poet Marquis Jean François de Saint-Lambert. Insistently repeated harpsichord notes suggest the distracted Morse code tapping of a pen against a desk. The drama of this intensely private, introverted music takes place not so much in the Château but in Châtelet’s head. After the first interlude, Principia sees Châtelet terrified that she will die without completing her translation of Newton, with rumbling timpani setting up a nervous energy that ultimately reaches a climax of raging brass and drums. The second interlude adorns harpsichord with chimes, sparkling percussion, pizzicato strings, and a gradual layering of wind lines, while Contre l’oubli (“Against oblivion”) sees Châtelet descend into thoughts of death, her work, and the transitory nature of life: “And I am afraid of sinking / With book and child / Into the vertigo of unconsciousness, / into the pit of oblivion.” The suite fades away with a restless coda, the harpsichord heaving with agitation.

Quatre instants and Émilie Suite are separated on the disc by Terra Memoria. Originally a string quartet commissioned by the Emerson Quartet, Saariaho adapted it for string orchestra in 2009. Although it has no text or program, it is nonetheless characteristically poetic in conception. In her program note for the quartet version, Saariaho describes the work as written “for those departed.” She writes: “We continue remembering the people who are no longer with us; the material—their life—is ‘complete,’ nothing will be added to it.” The work follows a smooth arc, emerging from silence and gradually building over a pizzicato heartbeat that is passed around the strings. Saariaho writes of “certain memories [that] keep on haunting us in our dreams,” and there is a subdued relentlessness to this music that grows at times to anxious keening. Though the troubled string lines fade ultimately into silence, a sense of unease remains, like a half-remembered dream. Letonja and the Strasbourg strings deliver a carefully controlled, sensitive performance.

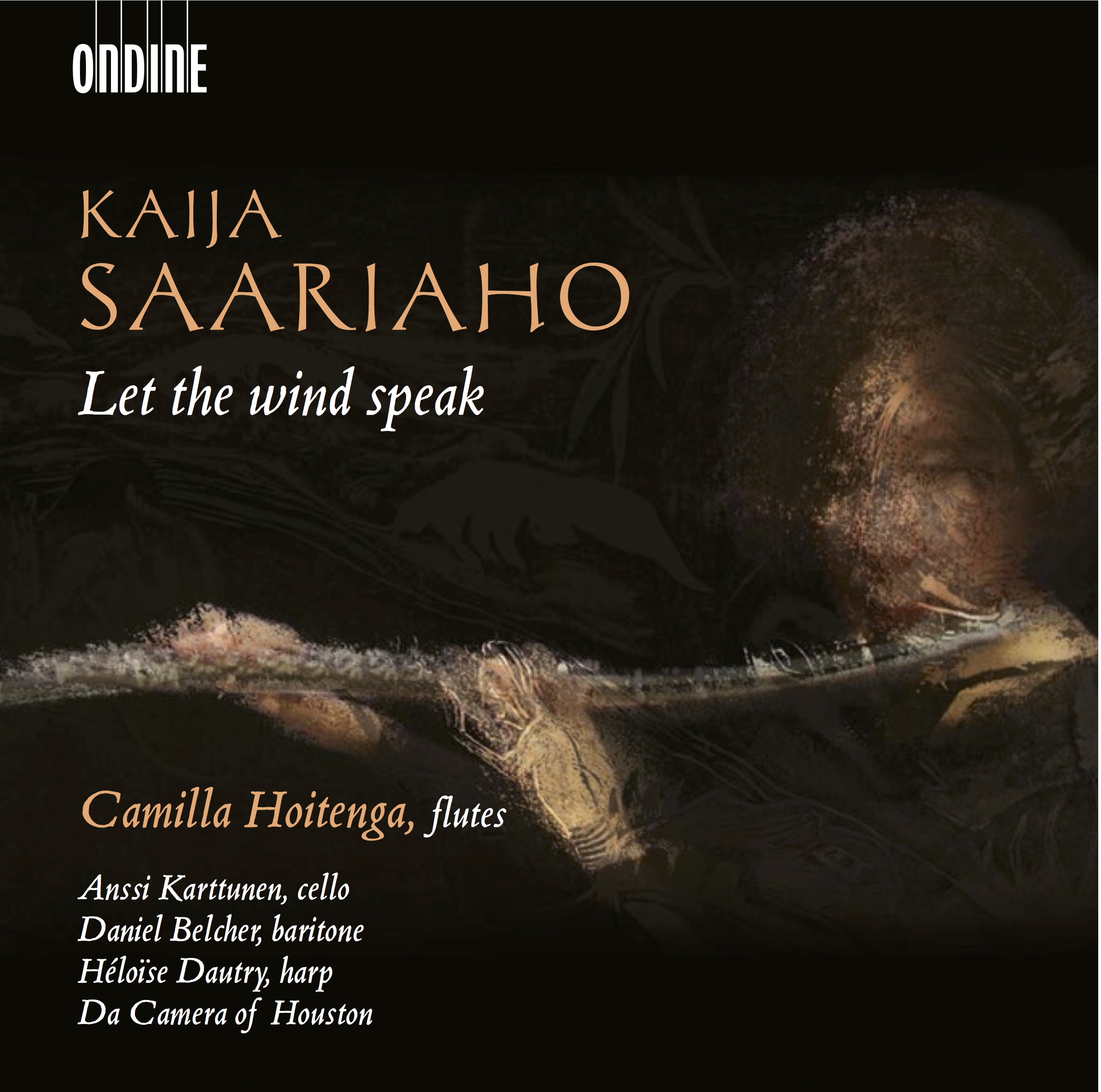

Let the Wind Speak

by Kaija Saariaho

Camilla Hoitenga (flute)

Daniel Belcher (baritone)

Anssi Karttunen (cello)

Héloïse Dautry (harp)

Da Camera of Houston

(Ondine, December 2015)

Ondine’s second Saariaho release of 2015, Let the Wind Speak, is not so much about Saariaho’s music per se as it is about American flutist Camilla Hoitenga’s relationship with Saariaho and her work. Naturally, the album focuses on Saariaho’s flute writing, and is infused with Hoitenga’s distinct musical sensibility. Some of the works collected here were gifts, while others are new arrangements assembled especially for and with Hoitenga; in all cases they reflect the long shared history between the two musicians.

Laconisme de l'aile, the most venerable piece on the album, was given to Hoitenga by Saariaho when the pair first met in Darmstadt in 1982—the beginning of a relationship that would span more than thirty years. Based on text from Saint-John Perse’s collection of poems Oiseaux (“Birds”)—words from which are hauntingly intoned by Hoitenga—bird imagery features strongly in the work. In her program note Saariaho writes that it is not so much birdsong as “the lines they draw in the sky when flying” that inspired her, and indeed the flute ducks and weaves, with swooping glissandi and fluttering ascents seemingly drawing lines through the air.

Saariaho wrote Dolce tormento as a birthday gift for Hoitenga in 2004. The work, for solo piccolo, is based on text from Petrarch’s Canzoniere No. 132, which Hoitenga delivers in resonant whispers, the piccolo picking up and amplifying her hissing sibilants. The piccolo lines ring out and sigh, an embodiment of the text’s evocation of love’s bittersweet torment.

As for the new arrangements (Hoitenga complains in the liner notes that Saariaho “hadn’t written enough flute music!”), both, interestingly, are of works in which Saariaho explores the relationships between pairs of instruments. Originally for violin and piano, Tocar is arranged here for flute and harp. Saariaho’s idea for this work was to pose a question about two instruments as different as the violin and piano: “How could they touch each other?” Flute and harp are certainly no less different than violin and piano, and although this creates a very different sonic effect to Saariaho’s original instrumentation, Hoitenga’s “flutistic” solutions to the challenges thrown up by arranging the violin line for flute still succeed in capturing this idea of two different instruments reaching out to each other in a “magnetism growing stronger and stronger.”

Of Oi Kuu, which was originally scored for bass clarinet and cello, Saariaho says: “It consists of elements which came to my mind when searching for a common denominator for bass clarinet and cello; harmony based on multiphonics of the clarinet; the multiphonics and color transformations of the cello; similar and different articulations; different colors in the same register.” These concepts translate remarkably well to bass flute and cello, Hoitenga’s multiphonics, singing-and-playing, and flutter-tonguing sparring with the shimmering harmonics and gravelly bass notes of Anssi Karttunen’s cello. Karttunen is no stranger to the work, the original version having been written for him and Finnish clarinetist Kari Kriikku.

Karttunen also features in the recordings of Mirrors I, II, and III interspersed across the album. These miniatures for flute and cello are really three iterations of a single work, which began life in 1997 as a part of the interactive CD-ROM Prisma. Mirrors consisted of a set of forty-eight fragments that the user could combine according to rules determined by Saariaho, and included spoken excerpts of text from Yvonne Caroutch’s Le livre de la licorne. The three versions on this album consist of Saariaho’s original score and one variation each by Karttunen and Hoitenga. While these pieces exist as individual works, motifs can be heard uniting the three, particularly a vigorous descending line that is heard in the cello in Mirrors I and II and in the flute part in the third variation.

Couleurs du vent, for solo alto flute, evolved out of material that began with …à la fume, Saariaho’s 1990 double concerto for alto flute, cello and orchestra. Material from …à la fume was later worked into Cendres for alto flute, cello, and piano (not recorded here), and Saariaho describes Couleurs du vent as “an improvisation over the material of Cendres” focusing on the flute’s “palette of flat and noisy colors.” Wind and breath feature heavily, and whispers and shakuhachi-esque blasts of air color Hoitenga’s sound.

The centerpiece of Let the Wind Speak is Sombre, a three-movement work commissioned by Da Camera of Houston for performance in the Rothko Chapel in Texas in 2012, and which sets text from Ezra Pound’s last Cantos. The bass flute that opens the first movement is a significant presence throughout the work, as is the soloist, American baritone Daniel Belcher. In a 2014 interview for Music & Literature, Saariaho explained:

I immediately began to imagine a dark instrumentation that, I believed, matched the paintings in the chapel. The color of the bass flute sound became a center of this palette; it had in my mind a close connection to Rothko’s work. The title Sombre appeared naturally from the character of the instrumentation, of the texts, and above all, of these last paintings by Mark Rothko.

Hoitenga’s percussive bass flute attacks adorn rich, velvety slides and rhythmic riffs. Multiphonics and whispers introduce a thicker texture of harp and strings before Belcher enters on the opening lines of Canto CXVIII. Hoitenga’s bass flute echoes his stuttering “t” on the word “shattered,” the music splintering apart.

Pound’s last Cantos are mournful and have an almost Haiku-like brevity. Saariaho explained her choice of text in the interview: “Their minimal form as well as their heartbreaking content seemed to suit this piece perfectly, and the language (English) helped me to renew my vocal conventions: I was able to explore new paths in my vocal writing.” The second movement, which sets Canto CXX, features the lines “Do not move / Let the wind speak / that is paradise” from which the album takes its title. The bass flute flutters around Belcher’s baritone, the harp a burbling accompaniment. Though the bass flute features heavily in Sombre, it is not the main focus of the work. Saariaho explained: “Sombre is not a concerto, but rather a chamber music piece with a very important solo part for bass flute, which is an instrument rich in effects. I felt I was breaking new limits of my own world with this piece.” Hoitenga executes these effects with an agile virtuosity that sacrifices nothing of the luxurious tone of the instrument.

Hoitenga was involved in the compositional process early, experimenting with sketched ideas in the Chapel and improvising in the space while Saariaho listened. In fact, the association with the Rothko Chapel is not just acoustic—the building and artworks also influenced the structure of the work. In Saariaho’s program note, she writes, “The formal solutions were also influenced by my visit to the Rothko Chapel with Camilla Hoitenga in March 2012. We were able to spend some time alone in the chapel with the paintings, and I noticed that of the eight walls, three walls are hung with impressive triptychs. Furthermore, some of my favorite paintings by Rothko have an overall form of two superimposed fields of living color.”

In sum, these albums present a swathe of new material and arrangements that not only provide an insight into Saariaho’s exceptional command of instrumental color and her agility as a composer, but which document the work of a composer as it evolves: the arrangements offer new opportunities to experience old material—as in the distillation of Émilie into a concert suite—foregrounding the developments that take place in a composer’s music as it grows and adapts via collaborations and ongoing relationships with performers through the years.

Angus McPherson is a Sydney-based writer, flutist, and teacher. His articles on music and flute playing have been published in Australia and overseas.