Losing Ground

by Kathleen Collins

(Milestone Films, April 2016)

Reviewed by Zoë Rhinehart

The Film Society of Lincoln Center series “Tell It Like It Is: Black Independents in New York, 1968-1986” ran in February 2015, revisiting films such as Spike Lee’s acclaimed first feature, She’s Gotta Have It (1986), as well as Bill Gunn’s Ishmael Reed collaboration, Personal Problems (1980). The series also featured Losing Ground (1982), a film by playwright, professor, writer, and filmmaker Kathleen Collins. Her film had debuted four years prior to Lee’s joint, at Irvington, New York’s Town Hall Theater. It was then screened once more, on local television station WNET New York’s Independent Focus in 1987—a year before Collins’s death—before the negatives were canned until “Tell It Like It Is.” Fortunately, thanks to a recent DVD release by Milestone Films, it will now be easier than ever to take a fresh look at Losing Ground and see how a film with so many literary qualities, and so focused on introspective drama, also coolly uses the exterior forces of music and imagery to reinforce Collins’s unique aesthetic sensibility. Though Losing Ground was resuscitated in the context of a particular showcase—one with a fairly political bent—the film ultimately resists classifications, as did Kathleen Collins herself.

One of the first feature films by an African American female filmmaker, Losing Ground was produced, written, and directed by Collins. It was her second and last film, realized with the help of Ronald Gray, her devout student, friend, and co-producer, and a diverse crew of twenty-two other students to whom she taught screenwriting and editing at New York’s City College. Although Collins was embedded in and dedicated to the city’s film community, “black female filmmaker” is a moniker that she firmly resisted. “I think of myself as someone who has an instinctual understanding of what it is to be a minority person,” she said in a 1980 interview reprinted in the DVD press kit. “That is someone whose existence is highly marginal in the society and understands it in the gut but will not be dominated by it. Therefore, I refuse all of those labels, such as ‘Black Woman Filmmaker,’ because I believe in my work as something that can be looked at without labels.”

Preoccupied with philosophical concerns, and fascinated with the interplay between imagery and poetry, Collins had serious literary interests. Her first film, The Cruz Brothers and Miss Malloy (1980), was based on her friend Henry H. Roth’s short story collection, The Cruz Chronicles. “I’m trying to find a cinematic language with real literary merit,” she stated, describing herself as a writer with particular preoccupations: “While I’m interested in external reality, I am much more concerned with how people resolve their inner dilemma in the face of external reality.” Erich Rohmer, who shared similar concerns about a wide range of subtle moral issues, was the only filmmaker Collins regarded as a direct influence. In particular, Ma Nuit chez Maud (“My Night at Maud’s,” 1967) inspired Collins’s naturalistic approach, with characters steeped in personal and societal conundrums, simmering beneath their exteriors. Both Rohmer’s and Collins’s protagonists struggle to find a palpable sense of passion in their beliefs, and are torn between preserving themselves and their ideas, and setting themselves free when confronted with other characters’ attempts to do the same. That said, Collins also admired Charles Burnett, a fellow member of the black independent film movement, and Lorraine Hansberry, the playwright of A Raisin in the Sun, whose “breadth of vision” she recognized as her own.

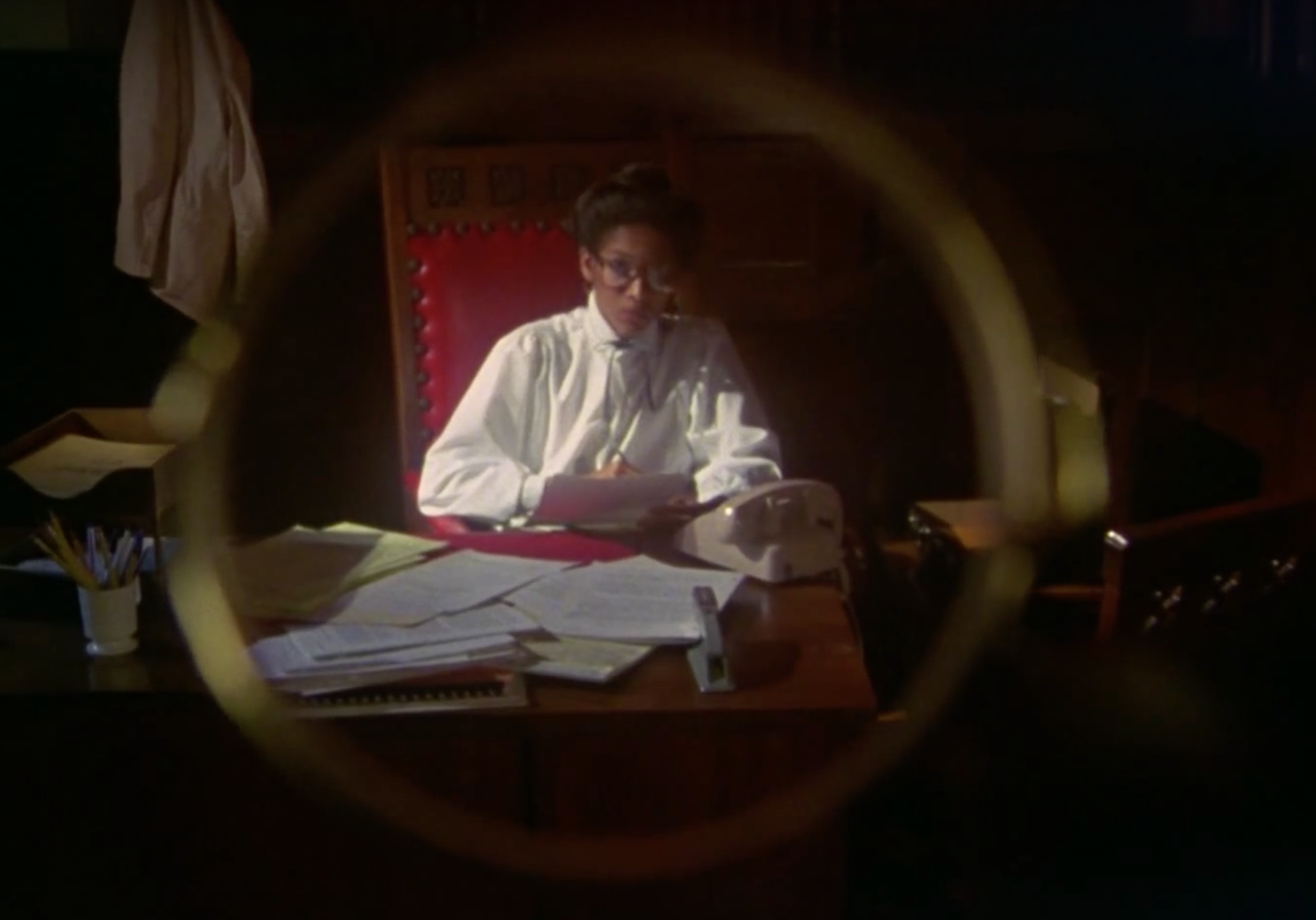

Characterized by Collins as a comic drama about a young woman who takes herself too seriously, Losing Ground centers on the imperfect marriage of philosophy professor Sara (Seret Scott) and her artist husband Victor (Bill Gunn). Early in the film, Sara sets up their individual and shared struggle: “Nothing I do leads to ecstasy,” she complains to him. “You stay in a trance, you ever notice that? A kind of private ecstatic trance; it’s like living with a musician who sits around all day blowing his horn.”

Seret Scott, Bill Gunn

Summer in New York has just begun and the semester has ended, leading Sara and Victor to take a house in upstate New York in order to give themselves over to their work. Victor has chosen the fictional town of Riverview, an idyll “where all those Puerto Rican ladies live in those old Victorian houses.” A self-described “genuine black success” after selling his abstract work to a Manhattan museum, he prowls the town with his sketchpad, moving lithely to a music all his own, drawing sprawling greenery and lounging women.

Sara continues to apply herself to her thesis on ecstatic experience, questioning where it comes from and how it manifests. She is not deterred by the library’s meager selection of Western philosophy, nor by her husband’s hyperactive flirtations with all he encounters—especially Celia (Maritza Rivera), a young Hispanic woman who floats through the painterly scenes of her home.

As she pursues the “ecstatic moment,” Sara gives in to something more concrete: she agrees to act and dance, to explore various realms of ecstasy, in a student’s thesis film. It’s a vaudevillian retelling of the song “Frankie and Johnny,” complete with bright, eclectic costumes and an array of dances—boogaloo, shim sham, jaywalk bump.

The student film introduces her to Duke (Duane Jones), the filmmaker’s uncle. An out-of-work actor and former theologian, Duke acts opposite Sara’s Frankie and instantaneously becomes her romantic interest. Sara’s search for the “ecstatic moment” and her marital strife are mirrored clearly in the plot of the film within a film. The relationships between Sara and Duke, Celia and Victor develop quickly and seamlessly; essentially all of the characters are more concerned with sustaining or realizing their interiors—though they are constantly subject to external forces—as if they are blowing into a dying fire.

Throughout the film, the characters’ internal dialogues burst into brazen exchanges and grandiose gestures in almost operatic fashion. The twin sets of lovers throw themselves into familiar tropes: the aloof wife, the mysterious lover, the philandering husband, the innocently sexual “other woman.” Not only do the character exaggerations make sense, they seem natural in this dreamlike New York. Like a big-stage operatic production, the costumes, locations, and music in Losing Ground are characters unto themselves.

Sara’s prim white blouse gives way to a colorful, flouncy dress and red flower in her hair as she grows closer to Duke and unravels her emotions. When Duke first appears to the viewer and Sara he is strolling around the film set, mysteriously sporting both a black cape and a top hat during the day. A Riverview fortuneteller had lamely suggested that Sara’s future included a tall man in a top hat; no other explanation is expected, offered, or needed. And the home that Sara and Victor rent seems more like a fantastic castle, with lurid, purple-lit stone staircases, solid antique pieces, and painterly interiors; the characters are often stationed by large bay windows, looking out at the landscape or calling out into the garden as if they were acting out balcony scenes from a vaguely surreal Shakespearian play.

Kathleen Collins

The production credits list only two songs as part of the film’s soundtrack: “Love Does Her Thing,” a simple, somber jazz ballad written and composed by Michael D. Minard (with whom Collins wrote a musical, Portrait of Katherine), and “Sabor a Conga” by Los Papines—an infectious Afro-Caribbean song. The musical elements of the film amplify the interior chaos and fleeting ecstasies of Collins’s characters.

Victor, in particular, is affected: Collins defines his ecstatic moments throughout the film with just one song. The piano, drums, and handful of trumpets that make up “Sabor a Conga” first rise up while he explores Riverview for the first time—sketching women chatting on porches, stepping lightly over children playing, the camera smoothly panning the sidewalks and capturing the sounds of its residents. The song seems at once to be a product of the community and a sound imposed on it by Victor, blaring joyfully as he walks woozily through what for him clearly becomes a dreamscape. The viewer sees the cozy streets and bright panoramas as compositions being painted in Victor’s mind. He washes the world in his desires and colors and then steps out into the town, possessed. In short, he easily conjures his soundtrack, a reaction to his reverie.

“Sabor a Conga” goes through numerous incarnations—frantic and intensified, slow and alluring—alighting from a scene into silence just as quickly as it takes off. When Victor first encounters Celia, she is dancing on the sand along the riverside, accompanied by a troupe of men slouching on nearby rocks, drumming casually. Victor approaches, and just as he grabs Celia’s hand to join in her spontaneous dance, “Sabor a Conga” picks up again brusquely, as if racing to catch up with the drummers. Fantasy and fact are fully in step as Victor broadcasts the music in his head that eventually drowns out the drums in reality.

This contrasts with the music of the next scene, which barely waits for the conga to end before picking up at a similar pace; it is the sound of Sara’s mind, her most immediate and accessible interior. It includes only the rapid clicking of her typewriter and her hurried, monotone voice dictating theological perspectives of experience that state that ecstasy only fully manifests after the moment it strikes. Earlier in the film, Sara recalls how she only feels ecstatic energy when she’s writing a paper: “My mind suddenly takes this tremendous leap into a new interpretation of the material, and I know I’m right! I know I can prove it! My head just starts dancing like crazy.” But she has trouble embracing this experience that she labels “so cold, so dry.” Here Collins seems to evoke Ma Nuit chez Maud: a violinist’s piercing concert, which Rohmer’s Catholic protagonist half-heartedly attends, is quickly juxtaposed with a scene of a more austere kind of passion—the “pervasive joy” of Christmas Eve mass.

Maritza Rivera, Bill Gunn

Sara’s scenes have an instrumentation of their own, striking in a way that is quite different from Victor’s. Her initial tune is simple, featuring a fluttering, introspective, and somewhat melancholy melody that wanders around the rental house with her as she inspects it for the first time. Unlike Victor, who seems to orchestrate his music, Sara is followed by her sounds like a traditional soundtrack, telegraphing feelings that she is unaware of until her internal ecstasy catches up with her external action. Her situation bears a stirring resemblance to that of Tchaikovsky’s one-act opera Iolanta: enclosed in a garden, singing and feeling flowers, the blind princess senses that others are experiencing things she cannot, and only gains her sight when she becomes fully aware that she is blind, connecting her mind and body, merging spirit with matter.

That's not to say that Victor is always in control, musically or otherwise. “Sabor a Conga” is a piece that does liberate itself from him, revealing itself to be more Celia’s property than his when the respective couples meet and dance. Bitter and intoxicated, Victor realizes he cannot control Celia’s rhythm, her tempo. She winds away from him, frustrated but unfazed, confident in her solitary, loose movements, grasping her ecstatic moment firmly.

Previously, Victor had broken down and shouted at Celia, complaining about the mambo pouring from his speakers as she posed for a painting in his studio, revealing his inability to fully orchestrate his seduction of her. Victor cannot comprehend the music that Celia seems to know at a deeper, more intuitive level: “Why do you always say ‘man?’” Victor eventually asks Celia. “It’s like a beat,” she replies. “The words go da, da, da. Then they need a beat at the end: man! That’s very American.” We realize—even if Victor does not—that Celia possesses what Victor can only try to grasp.

As Victor wrestles with his inability to literally move to his own music, Sara surrenders to ecstatic emotion—and the pain that often accompanies it. In the film within a film, Sara and Duke dance to a sensual and insistent saxophone that is both the soundtrack for their scenes and for their feelings. The student movie (and Losing Ground itself) end as the wailing music is cut short with a bang. All that is left is the sound of rushing wind, a supernatural bellowing that had battled the dialog for the viewer's attention when Sara and Duke first met. The unrelenting wind—dominant and foreboding—signals change, and we hear it blowing in long before the characters do.

Collins seems to literally drop us at the film’s conclusion. The explosive moment arrives and settles in mere moments; there is no resolution. Collins leaves her players frozen on the windswept plaza, poised to react in their own time. The conflict isn't resolved so much as it is stretched and pulled, fully in the hands and minds of the characters rather than given to the audience to impose upon them. All are left waiting for the final emotive note. And what does this note speak to, besides the sharp pang of frustrations finally released?

Seret Scott

While Kathleen Collins resisted gender and race classifications, it is clear that her characters, Sara in particular, do recognize themselves within those constraints, which plague their identities and lines of work, encouraging them to manipulate the roles they see available to them and that they envision for themselves. The pangs of emotional and creative frustration sound a note of existential dread when they tease each other about a pervasive “mulatto crisis.” The same holds when they play with their representations of (interior and exterior) selves, with Sara suddenly becoming an actress, and gaining a romantic interest, when her studies are put on hold, or when Victor becomes a “genuine black success” after his work is accepted into a museum collection—he then instantly moves from abstract painting to landscape painting and portraiture, and from playing the husband to playing the philanderer. The various intonations of these identity-related tensions are part of the beauty of the film, and it is difficult to not think of Collins in those terms, especially since Sara, who also taught at CUNY and strives to perfect her skills, seems to be her intellectual doppelgänger. In addition, so many of the stereotypes that existed in the 1980s persist today; when the camera reveals Sara as the professor speaking in the opening classroom scene, it still comes as a surprise, considering how meager representations of women of color still are, and how marginal female filmmakers remain in the film sector today.

That being said, the film plays off of the still-relevant theme of being “other”—whether by virtue of race, gender, social class, or sexuality—but without mining the usual black-white divide: Victor could just as easily been a white tourist who fetishizes the Latin women living in his vacation destination, while Sara’s unease brings to mind the more typical stories of black women trying to mold themselves into a white world. In Sara’s case, however, she seems to be out of step with her own husband and mother, trying to affirm herself and her passions with and without them. Using environments that elevate the operatic qualities of life through bright colors, studied dialogue, and songs and sounds tied to the urges and emotions of her characters, Kathleen Collins’s rare achievement was to masterfully cultivate the emotional tensions that come with grappling with individual identities, and the external gestures that shape and influence them.

Zoë Rhinehart is a New York-based writer. She writes essays, both personal and critical, about music, film, and emotion.