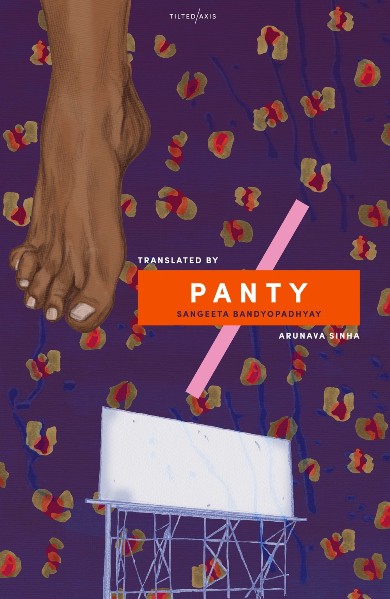

Panty

by Sangeeta Bandyopadhyay

tr. Arunava Sinha

(Tilted Axis, June 2016)

Reviewed by María Helga Guðmundsdóttir

Taken at face value, Sangeeta Bandyopadhyay’s novella Panty traces a straightforward narrative. It follows a woman newly arrived in Kolkata as she settles into an empty apartment, negotiates her tense relationship with her male lover, waits for a surgery she appears to need but not want, and dodges demons from her past. Face value, though, counts for little in the world of Panty, where the boundaries of facts and reality are in constant flux. The protagonist has barely been established when she witnesses the suicide of a woman who flings herself from a rooftop. She immediately latches on to a fragment of the stranger’s identity:

At once I made the death my own. “This is my death,” I said. I seemed to have rid myself of a weight I had borne some seven or eight months, and the foot I set down on the pavement felt completely new.

With this assumption of a stranger’s death, and this cryptic hint of unwanted weight being shucked off, the reader learns quickly not to rely on the protagonist as a purveyor of fixed truths. An unreliable narrator in the extreme, she conveys information that calls even her own integrity as a distinct individual into question. Even as the novella’s exploration of its narrator grows in intimacy, Bandyopadhyay refuses to pin her subject in place. Instead the woman is portrayed in a state of flux, a constantly shifting image, and Panty gives its readers the impression of a series of partial sketches overlaid on each other or a frame of film exposed numerous times. Occasionally, different layers of the image even seem to separate and meet each other face to face, as in this quiet encounter when the woman enters the Kolkata flat for the first time: “I found myself standing before a mirror stretching across the wall. The reflection didn’t seem to be mine, exactly, but of another, shadowy figure. I touched my hair. Eerily, the reflection did not.” A thematic preoccupation with self and identity might easily unmoor a text and send it drifting off into the metaphysical stratosphere. Not so with Panty: even the most abstract of its preoccupations are firmly grounded in the physicality of existence, especially in Bandyopadhyay’s earthy and frank depictions of sex and the female body. By all accounts, the novella’s sexual explicitness dealt a shock to the Bengali literary establishment when it first appeared in the respected literary magazine Desh in 2006. Though authors as diverse as Ismat Chughtai, Shobhaa De, and Mallika Sengupta preceded her in making sex a part of the literary terrain of Indian women writers, the boldness of the 31-year-old Bandyopadhyay struck a nerve with readers. Speaking of her novel Sankhini, also published in 2006, she remarked to the Calcutta newspaper The Telegraph,

I had talked openly about orgasms — one of my woman characters says, “I can feel it” — and people told me, “How can you be so open? There are some things that you can’t be so open about.” But I don’t think you have much control over what you write. It flows.

Bandyopadhyay has since been credited with “reintroducing hardcore sexuality to Bengali literature,” and on this front, Panty certainly lives up to the hype. Its frequent and detailed depictions of sex run the gamut from the sensual to the animalistic, yet remain subtly rooted in the erotic tropes of the Indian subcontinent, particularly through recurring imagery of rainwater and the monsoon. And while these prolonged scenes of intercourse are not unprecedented in the English-medium context of Western sexual liberalism, they are nevertheless refreshingly matter-of-fact.

Breaking taboos on female sexuality in a patriarchal society is a significant act in and of itself, but Panty’s sexual explicitness goes beyond mere iconoclasm. The female body, specifically including its erotic potential, is the linchpin of Bandyopadhyay’s probing of the limits of the self. This confluence is crystallized in the sequence of events surrounding the eponymous panty. Caught unawares and out of undergarments by her menstrual cycle, the narrator resorts to changing into a soiled panty she found in the otherwise empty apartment.

The premise is intimately familiar to those of us who menstruate—we’ve all had to jury-rig a solution to a surprise period—but receives scant mention in literature. Bandyopadhyay, however, takes this event and excavates its latent erotic potential:

I stood beneath the shower, miserable, while the cold water pounced on me. And then I remembered the black-and-yellow panty I’d found in the wardrobe. It was a panty worn by someone else, and mouldy to boot—I simply couldn’t use it, could I? A woman who wears a leopard-print panty must be quite wild. At least when it comes to sex. The question was, how wild? Wilder than me, or less so?

This line of inquiry results in yet another break in the continuity of the narrator’s identity. But in contrast with her voluntary and deliberate absorption of the suicide in the first pages, the transition wrought by the panty is as unexpected as it is all-consuming:

I slipped into the panty.

What I did not know was that I had actually stepped into a woman.

I slipped into her womanhood.

Her sexuality, her love.

I slipped into her desire, her sinful adultery, her humiliation and sorrow, her shame and loathing. I had entered her life, though I didn’t know it.

This encounter sets up the fundamental uncertainty driving the narrative: Where, if anywhere, are the boundaries between these two figures, the narrator and the woman she here dons like a garment? The ambiguous definition of the characters is mirrored by frequent shifts of perspective between first-person “I” and third-person “she”: some abrupt, others subtle enough to escape notice. Between them hovers a second-person “you,” the lover and the object of desire, masculine and unapologetically authoritative in the midst of uncertainty. Are there two distinct narratives in play, dealing with two nameless women whose connection was forged through the panty? Or a single woman, refracted through the looking glass of time and memory? Panty provides no pat answers.

These uncertainties find ample reflection in the novella’s structure. Time moves linearly in only a limited sense, and its twenty-one chapters are numbered seemingly at random. The range of the numbers, from 1 to 30, is suggestive of calendar dates, but if there is a code here to be cracked, it remains maddeningly elusive. Bandyopadhyay seems almost to tease readers, tempting them on a wild goose chase after order and linearity where there is none to be found. The hints of disorder in the narrative do not, however, extend to the prose itself. Bandyopadhyay is adept at rendering moods and environments without excess verbiage. Her sentences are short and concise, sometimes almost terse, at other times delicate to the point of fragility. Arunava Sinha’s English translation is crisp and clear, allowing the text’s complexities to rise to the fore. Occasional oddities in phrasing (“the cold water pounced on me”), which may suggest particular choices in Bengali, fit seamlessly into Sinha’s rendering.

“Sex is a form of self-discovery,” Bandyopadhyay writes. “You’re constantly striving to get at that someone else inside you—and and no sooner has sex afforded you that sensation that it isolates you, like the seed spat out by the exploding fruit.” She might as well have been describing the experience of reading Panty, for the novella is a curious dichotomy. At a linguistic level, it is eminently straightforward, but its direct language conveys a creeping sense of disorientation. As that disorientation builds, page by page, there are flashes of clarity, moments in which the stars seem to align—but they prove fleeting, giving way to a familiar, lingering unease.

María Helga Guðmundsdóttir is a translator based in Seltjarnarnes, Iceland. Her current projects include translating short fiction from Hindi into Icelandic.