On 26 August 1863 a brief notice appeared in the provincial German newspaper Neues Bayerisches Volksblatt stating that the skeleton of a young girl had been discovered atop the tower of Burg Lahneck, a medieval castle perched on a hill just above the city of Lahnstein in the Rhineland area of western Germany. Badly dilapidated after centuries of neglect, renovations had recently begun to revive the castle’s original gothic splendor. As the Volksblatt notice detailed, it was during these renovations, and in particular immediately after the completion of the construction of a new tower stair, that the skeleton had been discovered. Incredibly, the article went on to detail how a notebook had been found near the skeleton, wedged into the cracks of the parapet, that was found to contain a diary of the tragic circumstances of the deceased’s final days. Apparently, on the morning of 16 June 1851, the 17-year-old Scotswoman Idilia Dubb—on vacation with her family in Germany—had set off alone to sketch the Rhine and Lahnstein’s surrounding landscape. Anticipating the magnificent views of the castle’s tower, she passed through town, and followed a steep path that eventually leveled out at the entrance of the castle. Relieved to find it empty and ungated, she entered and, after exploring its courtyard, various rooms, and even a secret passageway, she eventually came to the base of a wooden staircase that spiraled upwards into the castle’s tower. Moments later, having ascended the stairs and stepped out onto the landing top the tower, her fate was sealed as the tower stairs gave way behind her and collapsed into the darkness below. Nor did the diary end there, documenting in graphic detail the terrors and torments of Ms. Dubb’s final days. It is, to be sure, an incredible story, a case of “truth,” in Twain’s words, being “stranger than fiction.” To some, in particular those of a certain outré aesthetic bent, it must appear a story of almost incomparable macabre perfection. How astonishing to witness here the decadent imagination loose the bonds of fiction, however briefly, to partake in the world.

Exemplary Departures

by Gabrielle Wittkop

Translated by Annette David

(Wakefield Press, 2015)

In “Idilia in the Tower,” the second story of French decadent author Gabrielle Wittkop’s Exemplary Departures, published in English-language translation by Wakefield Press in November 2015, we encounter an extraordinary text, a bearing of witness of just such an encounter, the decadent mind in contemplation of its own contours, fantasies, origins. Wittkop, née Menardeau, was born in 1920 in Nantes, France, a few hours’ drive southwest of Paris. She had always been fascinated as a child “by the animal skulls and skeletons that one finds lying around on beaches,” she later recalled in a 2002 interview with the French newspaper Libération, and her morose and misanthropic tendencies were reinforced by her father, who discouraged her from socializing with other children. Believing school to be a place where “children [are] forced into unnatural conformity by . . . imbeciles,” he instead home-schooled Gabrielle in the classics of world literature. “I read Alembert, Holbach, Diderot, Sade, at a very young age,” she later recalled. “I am a child of the Enlightenment.” After completing her education—which left her literate in Greek and Latin and fluent in English, French, German and Italian—Wittkop moved to occupied Paris, where she met and married Nazi deserted Justus Wittkop. In 1946 the two moved to Germany, where Wittkop would remain for the rest of her life—writing advertising copy, criticism, and, over the years, some dozen works of decadent fiction, "black books loaded with death, poison and gothic torments” as Eric Dussert wrote in Le Matricule des Anges. In 1986 Justus, suffering from Parkinson’s disease, decided to leave this world on his own terms and took his own life with Wittkop’s consent. Sixteen years later, in 2002, Wittkop, suffering from lung cancer, was to follow suit. “I intend to die as I lived, as a free man” [sic], she wrote in a farewell letter written to Bernard Wallet, her friend and publisher at the prestigious press Editions Verticales.

Structurally, “Idilia in the Tower” is a quintessentially gothic story, utilizing a restrained omniscient narration to establish the characters and setting with maximal clarity, while simultaneously utilizing plotting to temporarily withhold information and gradually build tension relentlessly towards its culmination in Idilia’s grisly denouement. But the true glimpse into Wittkop’s gift is found in the totality of the text’s individual moments, and the insight these give us into the very nature of the decadent writer’s engagement with the raw materials of a grisly event that transpired outside of the bounds of fiction. Early in the story, in a scene pregnant with pathos in which Idilia makes her ill-fated way towards the castle, we see Wittkop preparing the stage on which Idilia’s denouement will occur, creating a gorgeous backdrop of unrestrained lyricism—rendered beautifully in Annette David’s magnificent translation—against which the grim events that will soon unfold will appear in stark relief:

Idalia made her way between the dwarf houses that seemed to dance on one hip and then the other, and then along a road lined with vegetable gardens and stables resounding with deep, dark voices. A flock of geese crossed the path, disappearing into the filigree of the tall grass… Gradually the gardens became older, sweet peas coiled their thin tendrils round the lattice of the fencing… Small oaks, twisted and hunched, fir trees just sprouted, were clinging on to bare stone between moss, jovibarba and clumps of orphaned plants with mauve flowers.

As the story reaches its crescendo with Idilia, days into her nightmarish ordeal and starving and feverish with dehydration and terror, the narrative soars in Wittkop’s phantasmagoric telling of Idilia’s drift into hallucination. Lost in a shadow world of “hostile creatures, weeping faces, labyrinths with no exits [that] appeared through the mist,” it is, in the end, crows that accompany Idilia in her final passing, crows that “gather silently around her, in rows as at a theatre,” crows that came “from afar, from the dust of time, from medieval gallows . . . where poor sinners . . . sway[ed] with gouged-out eyes and feet turned inwards.” Days earlier, in the surreality of the immediate aftermath of the collapse of the steps that doomed her, shaken by “the roar of a volcanic eruption, of cities engulfed in the abyss,” gazing down into the void of the tower, Idilia had been overcome in the contemplation of “this vertiginous abyss whose attraction she dreaded.” “Attraction,” in the very midst of the deepest horror. Thus Wittkop, in exploring her response to the Dubb story, explores likewise the mindset of decadence itself.

Decadent literature’s classics are often set in the same locales as those of its immediate predecessor, the Gothic: barren wastelands, haunted chapels, subterranean passageways. But Decadence stands apart for the extraordinary, even unprecedented, violence and transgressive spirit it reveled in. Despite all their ghouls and gallows, the fundamental cosmology of high Gothic literature remained a fundamentally Christian one. With the arrival of Decadence—in Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du mal, Poe’s “Grotesque” tales, and most notably the Marquis de Sade's 1785 masterpiece The 120 Days of Sodom, or the School of Libertinage—a new faculty of violently transgressive nihilism was introduced into western culture. Mallarmé’s poetic syntax and its dissolution, as well as Rimbaud’s synesthetic hallucinations and intoxications, are signposts of that other component of Decadence: an increasing refinement of aesthetics and sensibility to extreme mannerisms of prosody and syntax. It is upon the work of these revolutionaries, and the generation of “high” decadents that followed them—Lautréamont, Huysmans, and Rimbaud, among others—that Wittkop's literary career is founded, as she herself repeatedly stresses, in interviews and in the many allusions and references she laces throughout her works.

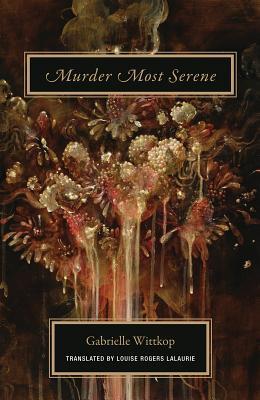

Wittkop’s debut novel, a slim volume appearing under the title Le nécrophile (The Necrophiliac), was first issued in 1972 by the notorious erotic publisher Régine Desforges. Penned in the most austere, classical prose, Wittkop’s fiction debut is a typical epistolary romance novel in form. In content, it is something else entirely. Comprised of the (fictional) journal of Lucien, an erudite, cultured, outré middle-aged Parisian antiques dealer, Wittkop’s novella details some two years in Lucien’s escapades in grave robbing, fornicating with the deceased—often, but not exclusively, in the privacy of his Paris apartment—and stealthily disposing of the swiftly putrefying bodies into the River Seine. The cumulative effect of Wittkop’s masterful juxtaposition of macabre content, classical rhetoric, and (narrative) cultural and historical erudition, is a work that has no obvious counterpoint in the works of Wittkop’s contemporaries, but that harkens back instead to the classics of high decadence. The Necrophiliac earned for Wittkop a minor celebrity status in European and outré literary circles, but a comparable reception in the English speaking world remained evasive, and it was only after Wittkop’s death some thirty years later that her works would start to find an English audience. In 2011, Don Bapst translated The Necrophiliac for ECW Press, and in 2015, Wakefield Press brought out Wittkop’s final two volumes: Exemplary Departures (1995)—a collection of five short stories, the last volume published during her lifetime—and Murder Most Serene (2005)—a brief novella first published three years after her death. We owe Wakefield a debt of gratitude for making these works available in English, for each reveals an entirely new facet to our sense of Wittkop the author and her œuvre.

Murder Most Serene

By Gabrielle Wittkop

Translated by Louise Lalaurie

(Wakefield Press, 2015)

In Murder Most Serene, first published posthumously in 2005, we encounter Wittkop exploring, in narrative form if not in content, an extremely confrontational, transgressive approach. This strain has always been central to decadent literature, and indeed we can trace its origins to the central text of the genre—Sade's The 120 Days of Sodom—reviled by most but held in almost unrivalled esteem by the keepers of the genre’s inner sanctum. Structurally a rather conventional work—set in a sickly Venice in the final years of the eighteenth century, and documenting the series of mysterious, gruesome murders by poisoning suffered by the succession of wives of antihero Alvise Lanzi— Murder Most Serene instead embeds Sade’s transgressive legacy within its narrative and form. On the one hand, this takes the form of a narrative worldview positively saturated with revulsion towards nature and the biological world. When we first encounter Catarina, for example, the first of Lanzi’s wives and late into her pregnancy, she is described as with “belly . . . slimy, glistening . . . heavy with chuckling liquids . . .entrails, muddied waters, cartilage . . . greenish-yellow, burgeoning spongelike growths piled one on top of the other.” Elsewhere the narrator states, in passing, that “never have so many monsters been brought forth; some with their skulls flattened as if between two planks of wood, some without eyes or mouths... some with an embryo caught in the anus, some with ears protruding from their backs like wings; some with fingers on their shoulders.” This world-weariness manifests in another fashion in the narrator’s explicit denials of the validity and purpose of narrative as such—stating, in the volume’s opening pages, that “syllogistic . . . premises and their ornamental setting alone shall be our entertainment”—and concerted and unrelenting barrages of vacant declarative sentences concerning unidentified, and irrelevant, characters follow: “Someone enters a drawing room . . . Someone looks at their hands. . . Someone reads a report … Someone makes the Sign of the Cross.” The end result is by far the most radical of Wittkop’s works thus far available in English, a fascinating—if aesthetically dubious—exploration of Calvinistic world-weariness.

To turn from Murder Most Serene to the second of Wakefield’s two recent Wittkop editions, Exemplary Departures—first published in 1995—is to encounter a remarkably different stylistic approach (that Wittkop composed the two books consecutively only amplifies the breadth of her proficiency). Whereas Murder Most Serene’s narrative was, in effect, an anti-narrative, hostile to reader and dramatic convention alike, in Exemplary Departures English language readers finally encounter Wittkop as master storyteller, indulging in rhapsodies of lyricism and virtuosically deploying the conventions of the gothic genre to achieve maximum aesthetic pleasure. Stylistically, the collection could hardly be more traditional, as much classically gothic in spirit than transgressive decadent. Here we witness Wittkop ostensibly relaxing a bit from her desire to enact her predecessors’ ideals, and see her instead simply and unapologetically indulging in the sumptuous particulars of the conventions of the macabre. In focus, too, the works are worlds apart. While the form and style of Murder Most Serene is all disgust and aggression, the five stories collected in Exemplary Departures—all culminating in the deaths of their protagonists, “[drawn] from the remnants of real-life anecdotes”—are expansive in design, traversing disparate forms and styles, each itself illuminating differing perspectives on death, existence, and the material cosmos. “Baltimore Nights,” a fictionalized account of Poe’s final days, is a bravura performance as Wittkop portrays, in language of precise articulation and taut restraint, the sluggish, chaotic disorder of a mind in its final descent. “It is not impossible that some unlooked-for optical improvement may disclose to us, among innumerable varieties of systems, a luminous sun, encircled by luminous and nonluminous rings, within and without, and between which revolve luminous and nonluminous planets, attended by moons having moons, and even these latter again having moons,” Poe intones at one point from the depths of a drunken stupor. In contrast “Mr. T’s Last Secrets,” a fictionalization of the true historical disappearance in the Malaysian wilderness of American businessman Jim Thompson (1906–1967), Wittkop heads off in yet another stylistic direction, utilizing a dual narrative—one part omniscient narrator, the other quoted excerpts from unattributed speakers—to create a labyrinthine, disorienting effect, that embeds ambiguity, even contradiction, into the center of the story. We even encounter Wittkop expressing a conception of nature that, in its depth and rhetorical flight, can only be described as romantic sublime. Her omniscient narrator intones in the story’s opening pages that

Nothing was wasted in this cosmos . . . where everything bears fruit and decomposes, swallows, digests, expels, struggles to exist, copulates, germinates, hatches, and dissolves so as to grow again and again in an eternal ebb and flow, one after the other . . . death embraces resurrection, the two of them twinned like day and night.

Indeed, the epiphany seems to arise precisely in the contemplation of the world in all its materiality and organic profligacy, precisely the contemplation that we have suggested elicited Murder Most Serene’s puritanical world nausea.

Exemplary Departures’ jacket copy describes its contents as “[drawn] from the remnants of real-life anecdotes.” The phrasing is precise in its ambiguity. Throughout the collection, fact bleeds into fiction, without any clear demarcation as to where one ends and the other begins. In some of the stories collected here—the aforementioned Edgar Allan Poe and Jim Thompson—the facts center around the inaccessible circumstances of the final days of actual persons. In others, the events portrayed are the pure inventions of Wittkop’s mind. In one case, however, the story “Idilia in the Tower,” the situation is more complex, and illuminating. In her postscript to Wakefield’s Exemplary Departures, translator Annette David notes that “the alleged original diary’s remarkable condition and its numerous errors and fallacies raise suspicion as to whether the story is a hoax.” In fact, a search of the historical record has uncovered challenges to the veracity of the Dubb story dating back to 1864, less than a year after the appearance of the original Neues Bayerisches Volksblatt notice, and the consensus today is that no such person as Idilia Dubb ever existed. And yet, simultaneously, there is a very real, and indeed very crucial sense in which she did exist, even if not as a material person. For it is a fact that a notice announcing the discovery of her skeleton appeared in the 26 August 1863 Neues Bayerisches Volksblatt (an image of it can be found in the University of Bonn’s digital archive of that paper), and did appear in the “factual” context of reportage, not the fictional context of literature. In the process of writing this review I enlisted the help of a German friend in translating the little research on the Dubb myth that is available in German. At the end of her generous, meticulous summary of the literature, most of which concerns the evolution of the Dubb legend as it evolved and proliferated in the months and years after its original appearance, my friend signed off with the remark: "For me the central question raised here is: What happened in 1863?" Indeed, her question is applicable to more than just the story’s subject. Who planted the Dubb story in 1863, and why? More generally, from whence arises the impulse to transgress social and ethical norms via the medium of writing? It certainly does not seem trivial that the Volksblatt event occurred when and where it did, at the zenith of Decadence. From what depths came—and comes—this impulse? It is in pursuit of just such questions that Gabrielle Wittkop devoted her life’s work.

Mark Molloy is the Reviews Editor for MAKE: A Literary Magazine.