The following text was written for the occasion of the U.K. launch of Music & Literature no. 6 on 21 November 2015 at The Forum in Norwich, England. The event was presented in collaboration with the University of East Anglia and the British Centre for Literary Translation.

I was going to talk about what happened last weekend in Paris, because it is something no one can stop talking about, but no one, including me, can somehow find words for. This picking over of words, already so well-used, can seem futile.

Joanna Walsh delivers her thoughts on Paris in Norwich, England.

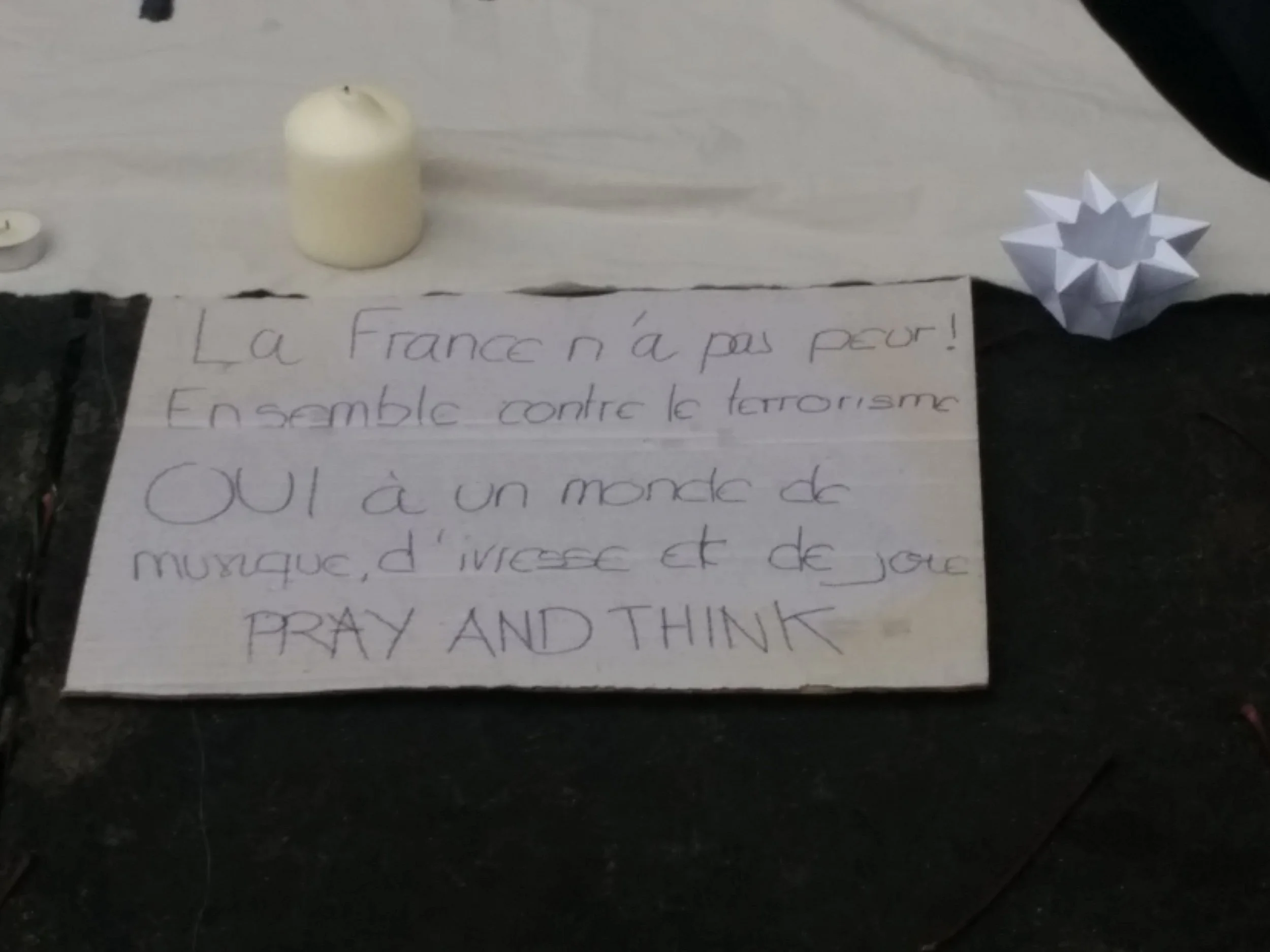

Last Sunday in Oxford I attended a vigil. Two to three hundred people, most of them French, walked from Radcliffe Square through the center of Oxford to the French Cultural Institute, La Maison Française. I stumbled my way through “La Marseillaise” (I can’t remember half the words), there was a minute’s silence, then people came forward to place, on a cloth, flowers, candles, newspaper clippings, scribbled notes, photographs, small, and sometimes unidentifiable objects.

And I thought about Dubravka Ugrešić, and I thought: In a state of national emergency, how do stories continue to exist?

Dubravka Ugrešić is a writer who has existed in a state of national emergency since the 1990s, when she was branded one of five “Croatian witches”—women writers who ridiculed the nationalistic propaganda of President Franjo Tuđman. “Everyday life around me changed and became threatening,” Ugrešić said. “When reality became morally and emotionally unacceptable, I spontaneously started to protest.”

Living in exile in Amsterdam over the intervening twenty years, Ugrešić has not become a Dutch writer but continues to carry this state of national emergency around with her. “Before, when I was ‘local,’” she once said in an interview for BOMB, “I tried to write ‘globally.’ Now, when I am not ‘there’ anymore, it appears that my themes are more connected with ‘local.’” In “Goodnight, Croatian Writers, Wherever You May Be,” the essay that got her into trouble in the first place, she writes “Instead of being at the frontier of my country, I would rather walk the frontier of literature, or sit on the frontier of freedom of speech.” “Nationalism,” said Ugrešić in the BOMB interview, “is as dull as a toothache. It sings the same song, always . . . Nationalism also means being in power to change cultural memory.” Culture is seldom made by those in power, but its frontiers are often built by them. Words, which have as many beginnings and endings as bricks may be used to build frontiers, or museums, or other structures.

How?

“I was obsessed with the ‘literariness of literature,’” said Ugrešić, “and which literary texts result in an art of literature.” Never has a writer been more aware of how one narrative depends on another. Her short novel, Steffie Speck in the Jaws of Life, is a “patchwork,” not only of story, but of horoscopes, advice columns, and women’s magazines. In Lend Me Your Character, Ugrešić over-writes the classics. Retelling other writers’ work, she said, “was probably more of a liberating and playful act as a reader, which I used to be, than a postmodern gesture.” A writer with a profound understanding of the spiral of artifice that is writing, Ugrešić’s work insists that literature is never still. She has a way with sub-clauses, with parentheses: her writing argues with, fights against itself. Breaking down the frontiers between life and lit, Ugrešić insists on opening up the jaws of life to insert the ugly, the awkward, the comic, the annoying, the trivial, and especially the kitsch.

The Museum of Unconditional Surrender begins with the description of a peculiarly odd range of objects discovered inside the stomach of a gigantic walrus named Roland in a museum in Berlin. They include a pink cigarette lighter, a small doll, a box of matches, a baby’s shoe, a little plastic bag containing needles and thread . . . “The job of collecting is a nostalgic and consoling activity,” says Ugrešić, “but it can’t bring to life what is lost.”

“Convalescence had begun in the flea market,” she writes in Thank You for Not Reading, “but I’m not sure culture can be revived by the mere sale of cultural souvenirs . . . If an authentic language of culture does appear, and I’m sure it will, it will come from other sources. One source will be nostalgia.” Nostalgia is a human feeling not primarily for objects, but for the feelings, ideas, and processes that attach to them. It is a feeling for the object as a moment that embodies these things, which may be one reason Ugrešić is so interested in photography.

“Nostalgia is dangerous,” says Ugrešić, “because it encourages remembering.” In The Museum of Unconditional Surrender, each exile is in charge of a matchbox museum, a wunderkammer of the infinitely small, and fractal, in which they keep the ineffable, the nuanced, the material, the personal. Writers are in a special position here, for they are not historians, or politicians, or news reporters—though they may feel the pressure, in a state of national emergency, to be any or all of these things. What writers can be, perhaps, are up-scalers of unconsidered trifles, rag-and-bone merchants of the pointless, bricoleurs. While there are writers—and publishers that dare to publish them—“memories,” which are such slippery things to preserve, will not be, as Ugrešić puts it, “confiscated.” We will write each old story in a new way, just as it has written us.

In a state of national emergency, what we must do, above all, is keep writing.

Joanna Walsh is the author of Hotel, a memoir, which was published internationally in 2015. Her latest book, Vertigo, is published by Dorothy, a publishing project, in the U.S. and will be released by And Other Stories in 2016. She also wrote the story collection Fractals, published in 2013.