A feature by Cynthia Haven

And so you were the chosen scapegoat for that society for a while.

I didn’t feel like a scapegoat. There are many anonymous civilians who were scapegoats and nobody will ever hear about them or have a chance to remember them: many people were killed, chased out, mobbed, robbed, humiliated, fired, many people left, many emigrated. All because of local neo-fascist strategies. The biggest victims in Croatia were ordinary people of Serbian ethnicity. In Bosnia, the biggest victims were Muslims. And so on and so forth. Those who were responsible for this “silent persecutions” were never brought to the justice. And they will never be. Because justice in Yugo-zone obediently serves the people in power. . .

A feature by Joanna Walsh

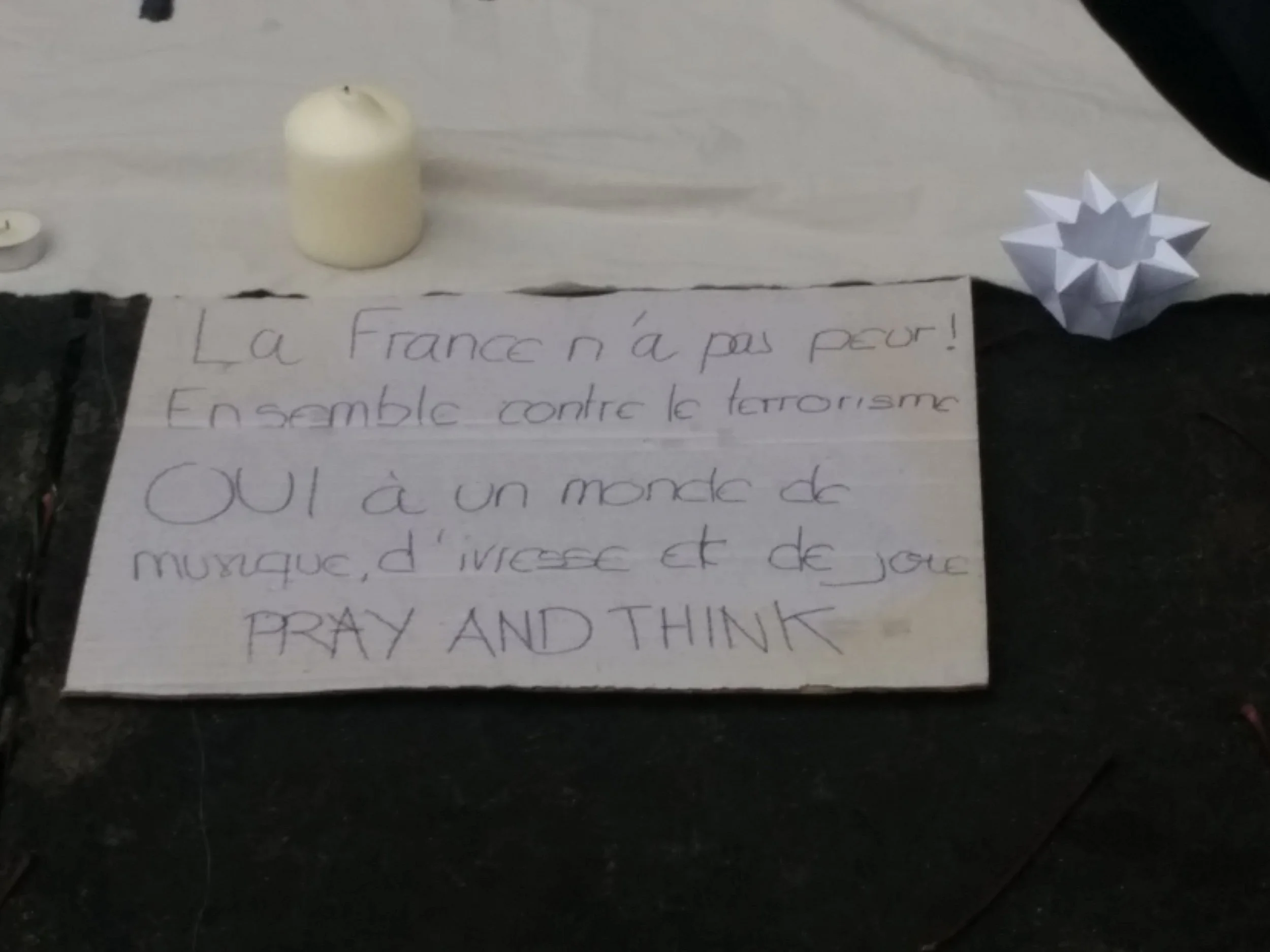

Last Sunday in Oxford I attended a vigil. Two to three hundred people, most of them French, walked from Radcliffe Square through the center of Oxford to the French Cultural Institute, La Maison Française. I stumbled my way through “La Marseillaise” (I can’t remember half the words), there was a minute’s silence, then people came forward to place, on a cloth, flowers, candles, newspaper clippings, scribbled notes, photographs, small, and sometimes unidentifiable objects. . .

A feature by Daniel Medin

DM: To what extent did the war change your approach to writing? On the one hand the answer seems obvious: Berlin and Amsterdam became settings for your fiction, and the experience of exile a principal theme. And yet I was struck while rereading Lend Me Your Character, since the stories featured in that volume are remarkably consistent, despite having been published originally between 1981 and 2005.

DU: The war did not change my approach toward literature. I have always cared more about how things are written than what is being written about. But the war changed me. It brought with it new themes, preoccupations, and thoughts. And of course: exile, a changed life, a deeper knowledge of human nature, fresh stimulations. These were powerful experiences. However, I had no desire to convert them into a memoir or autobiography.

I would never judge the quality of a literary text by inspecting whether the writer’s experience was real or false; the text itself betrays the author. A careful reader only feels comfortable in the text when the author feels comfortable in there too: it’s a secret communication between them.