A feature by Cam Scott

Jazz, one understands, is freedom music. As an art form of African-American origination, fashioned in the crucible of Jim Crow and the endless aftermath of the transatlantic slave trade, jazz has always demonstrated the immanence of creative resistance to any instance of oppression. As historian Gerald Horne writes, jazz “is the classic instance of the lovely lotus arising from the malevolent mud.” For this reason, however, a dubious American nationalism tends to inform popular understandings of the form. Jazz spans the world, not as an American export, but as a music of African provenance, distributed by the machinations of empire. Defying the historical strictures from which it originates, this plural music issues a deep and de facto internationalism, anti-colonial at its core.

A feature by Chase Kuesel

On July 7, 2013, Keith Jarrett bracingly took to the stage at the Umbria Jazz Festival in Perugia, Italy. The momentousness of the occasion was not lost on anyone: just six years earlier, Jarrett had become the first artist to ever be banned from the festival by director Carlo Pagnotta, for delivering a profanity-ridden condemnation of photographers in the audience. Seeking to avoid a similar incident this time around, Pagnotta issued a preemptive plea to the crowd to put their cameras away and to greet Jarrett with a standing ovation.

Right, the community—again, we’re talking about people and music. They’re inseparable. So I was living in Boston, meeting those people, and it was 1998. The World Cup comes. It was always interesting to see how people prepared the party before the game—the kind of vibe, the hats, the warmth, together, and passion. There’s always passion in everything. Passion in drinking, passion in arguing, passion in playing, passion in being together. Really, there’s something so wonderful about it. It was really refreshing to me, the way people were celebrating life. And everyone was showing up to support the gigs, and dancing, and singing the songs. It was so new to me. Even now, you think about jazz in the United States, and you think about Israel… People sing old songs in Israel if they come to one of those evenings where everyone sits together and sings, but if you go to a party or a bar to listen to old music—unless they really love it, it’s not the same. It’s really mind-boggling. It’s really a beautiful thing.

A feature by Whitney Curry Wimbish

Flautist and composer David Bertrand plays the flute like an invitation: come hear this instrument for what it is, not for what you might believe it to be. It’s a welcoming approach that not only demonstrates something of the flute’s innate fine character and ability to blend with all other instruments, but it also rejects the idea that the instrument may only be played by certain people.

“I was told in no uncertain terms: ‘The flute makes no sense. You should play something else. You should be a saxophonist. If you play this much flute, you should have no trouble with sax. The flute is a white people thing. It has nothing to do with jazz,’” Bertrand recently told me. “But in Trinidad, we talk about oppression as a fight dog. Either you bow down and acquiesce, or you fight back. I’m playing the flute to fight.”

A feature by Whitney Curry Wimbish

Oh: What I really love about playing this music is this sense of resourcefulness. You have to be ready for what’s going to come to you, and that flexibility transfers into other parts of your life. The skills you learn when you’re first studying music serve you in different ways. Resourcefulness, compromise—those are useful tools for good human beings…

A feature by Spencer Matheson

One of today’s leading pianists, Dan Tepfer has played with some of the great names in jazz: Mark Turner, Billy Hart, Ralph Towner, Joe Lovano, Bob Brookmeyer, and Paul Motian. His most recent recordings include Decade (July 2018), his second album with Lee Konitz, and Eleven Cages (June 2017), with the Dan Tepfer Trio. His current project, Acoustic Informatics, uses a concert piano that can be controlled by a computer, for which he has written programs that respond in real time to his improvisations. This is an edited version of an interview conducted in Paris in October 2017.

A feature by Andrew DuBois

The island of Newfoundland seen from a map looks like fractal geography as printed fact. The island proper—the biggest part by far of the whole of what we call The Rock—has a kind of polyp on its southeastern-most side. It looks like an island that looks roughly like the island from which it hangs; and hang it does, because it is not an island at all, but a peninsula. It’s called the Avalon Peninsula—king and queen-fed courtly dreams of paradise in that name—and the closer and closer you read on the map, the more it looks like a living geological Mandelbrot Set. The ocean gives way to big bays, big bays to smaller ones, which give way to harbors and coves and little inlets; just like the Trans-Canada Highway, which starts here before stretching its ribbon of asphalt it seems like forever, gives way to smaller highways such as 70, 75, 80, which in turn become Main Streets and Water Streets and finally devolve into something called “drungs,” which are rural Newfoundland lanes. Avalon looks from here like the claw of a crab—cartography is maritime destiny—or maybe, in the knuckles and muscles and bones of its towns and the blood and veins of its roads, it resembles a damaged, but very much living, human hand.

A feature by Ben Ratliff

BR: I want to know more about your grandfather. There’s an airport named after him, right?

MT: Yes, there is now. It’s in Ohio.

I know only a little bit about his time training African-American air-force pilots during the 1940s.

Yes, exactly, he trained pilots in Tuskegee. He wasn’t enlisted, but he was one of the non-enlisted who trained pilots. I don’t remember how many trainers they had, but he was one of the main guys that did it.

A feature by Kevin Laskey

Because of Coltrane’s musical stature and the public nature of his funeral, the performances by Albert Ayler and Ornette Coleman had the power to establish the conventions of a modern jazz requiem—how to properly memorialize a member of the jazz community. In their performances, Ayler and Coleman memorialized Coltrane not through imitation or pale attempts at resurrection, but by organically integrating aspects of Coltrane’s playing into their own distinct styles—a form of musical signifyin(g).

A feature by Samuel Cottell

Panichi frequently alludes to the lessons he learned from his time in the BMI workshops with Bob Brookmeyer: "Repetition and change are the most important variables in composition. The hardest thing in music is to know when to introduce change. Brookmeyer used to say, 'Keep going in a particular direction until you think you’ve overdone it; then you can go somewhere else.'"

A feature by Kevin Sun

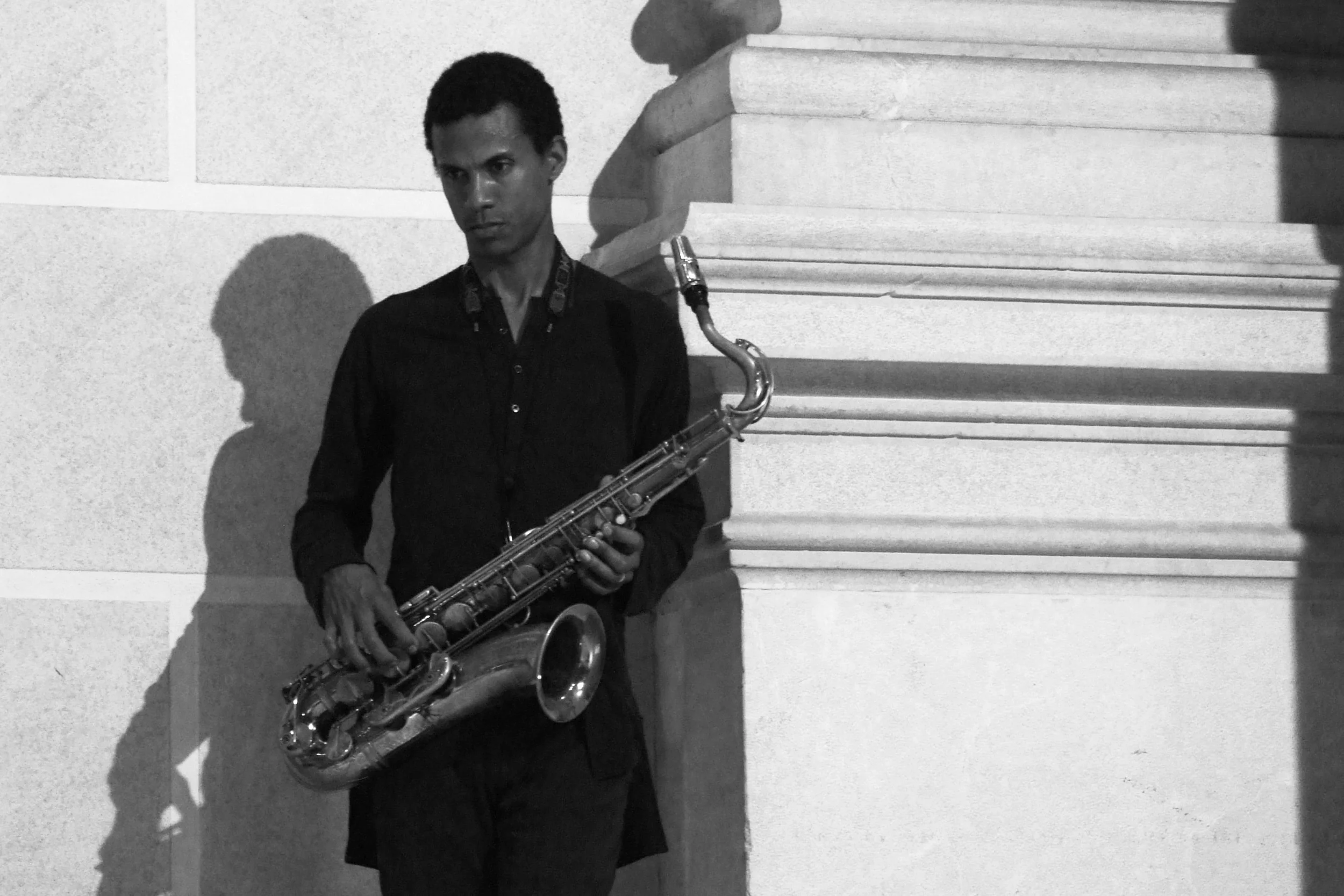

“He’s really unafraid to fail,” Ethan Iverson says. “Career shit, making the tune work—none of that matters; he just sees it as an epic cycle, and that’s why he’s Mark Turner. That’s why he gets to these great heights, because he has this other kind of warrior in him for whom failure is just another pleasant way to pass the time, you know?” Saxophone playing, just like anything else, has its fads, but Turner seems stylistically to have planted his feet firmly and pointing slightly inward since he moved to New York. As Turner himself points out, deciding what to practice is not just a day-to-day affair, but part of a lifelong commitment toward realizing an artistic self. “A lot of that in particular is just gradually clarifying your aesthetic and trying to figure out what you need to do to reach that aesthetic,” he says. “Otherwise, you can be practicing for millennia! I mean, you can practice one or two things for hours and hours and hours, twenty-four hours a day until you die. You have to decide on something.”

A feature by Kevin Sun

“Mark’s very lyrical, and that’s one of the things that moves me. A lot of students now can get around their instruments, but I don’t hear the lyricism. Now, you think about something like if I had to replace Mark,” says Billy Hart. “Of course, I had to deal with some possibilities, but there was nobody I could say, ‘Okay’ [snaps fingers]. Nobody. So then, for the first time, I had to think about it like when Miles had to replace Coltrane.”

A feature by Dan Bilawsky

“There’s the famous story of somebody asking Michelangelo how he created the statue of David, and he said, ‘Well, I took a hunk of marble and chipped away everything that wasn’t David.’ I love that, because, to me, as a musician, I try so hard to get things right, but no matter how hard I practice, there are just some things that I can’t get. And I’ve come to understand that those things that I just can’t get, no matter how hard I try, are the marble that’s supposed to remain. If we all could do everything, we’d all sound the same. But because we all have strengths—and just important, weaknesses—there’s really a differentiation and a beauty of variety. Not only are you not expected to get it all right, but the stuff that you don’t get right helps to inform your musical personality or who you are. It’s helpful for me to talk about because I need to be constantly reminded [about it], because I can tend to really beat myself up about the stuff I don’t get right.”

A feature by Jesse Ruddock

Avishai Cohen has been working since he was ten, when his job was to stand on a soap box and play trumpet for a big band. Raised in Tel-Aviv, the youngest of three jazz prodigies in one house, his music is persistently lyrical, often sublime, and intensely playful. Cohen stands out on stage in a way that’s athletic: his lead’s to follow. What the body has to do with the soul can be heard in the tone of his trumpet, that strange precise math of breath and spirit. On Dark Nights, the third and latest album from his trio Triveni—with Omer Avital on bass and drums by Nasheet Waits—Cohen’s tone is clearer than any voice. The songs all go slow but never keep you waiting to find out what they’re trying to mean. This interview took place high above Broadway Avenue in Manhattan, one afternoon before Cohen played three sets through midnight with the Mark Turner Quartet . . .